In the quest to understand our planet’s ancient past, paleontologists and archaeologists rely on fossils as tangible windows into prehistoric times. Yet throughout history, this scientific pursuit has been plagued by frauds, hoaxes, and misidentifications that have sometimes led even the most esteemed researchers astray. From elaborate pranks to financially motivated forgeries, fake fossils have repeatedly challenged scientific integrity and methodology. This article explores notable cases where fabricated fossils nearly deceived—or temporarily did deceive—the scientific community, highlighting the ongoing tension between scientific discovery and human deception.

The Piltdown Man: Britain’s Most Infamous Scientific Fraud

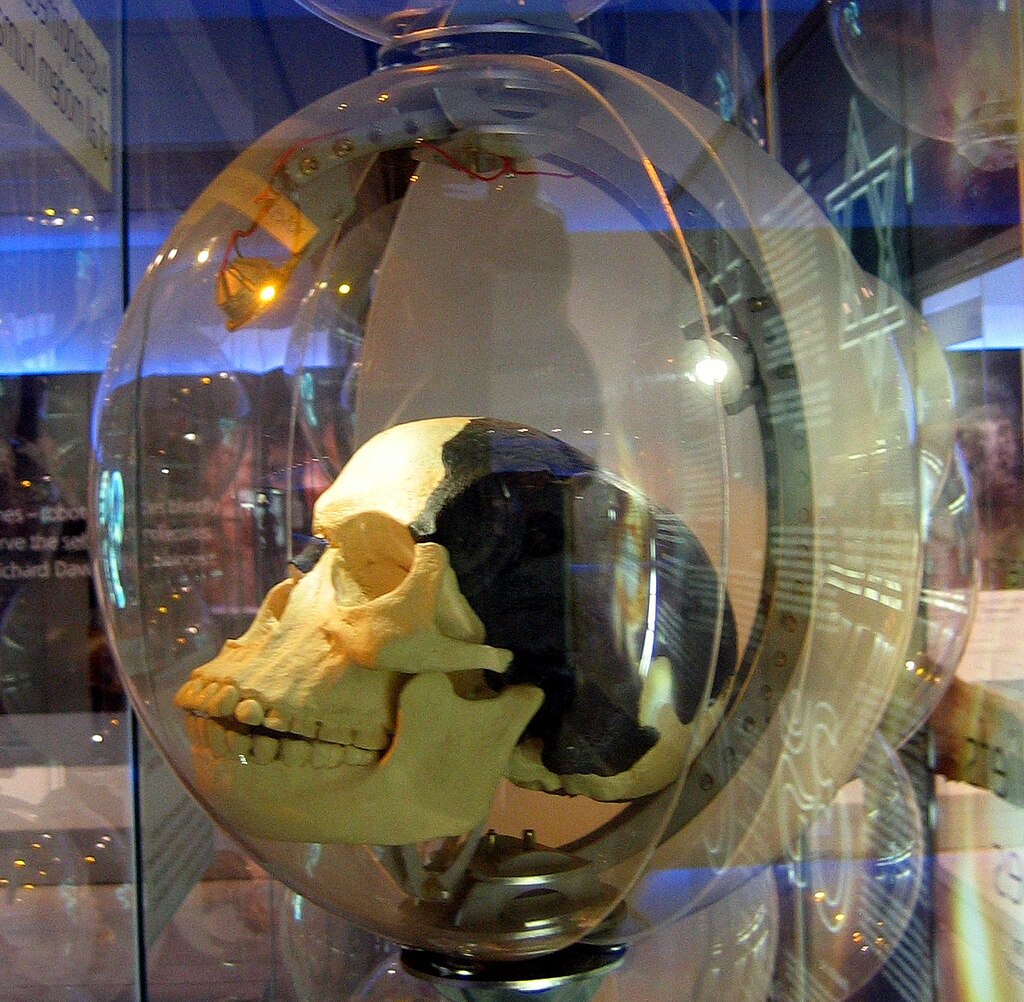

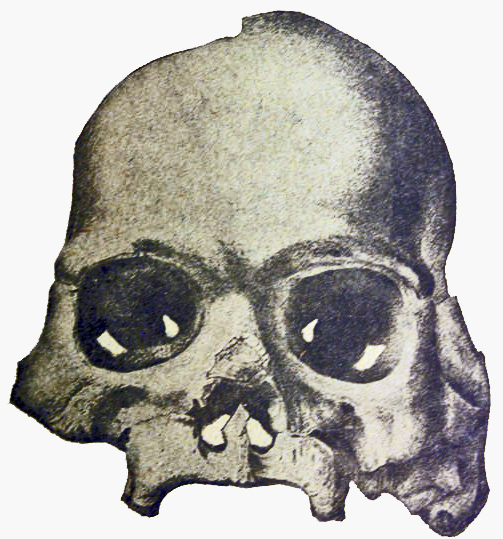

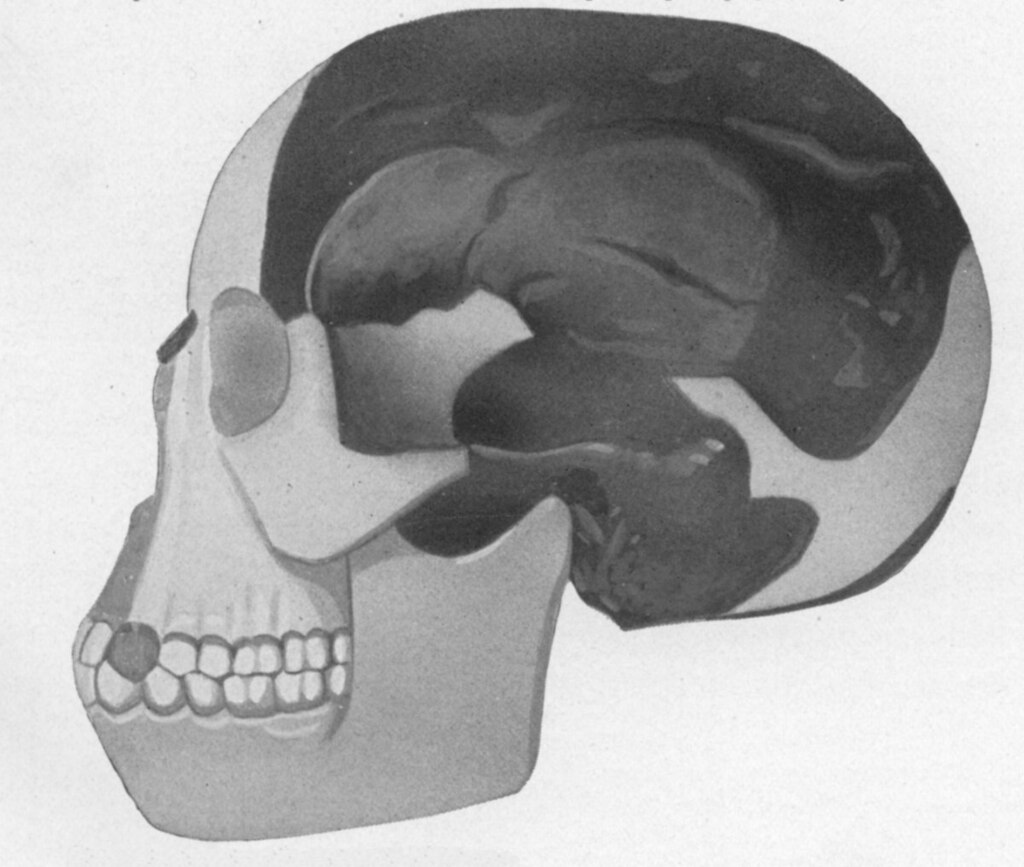

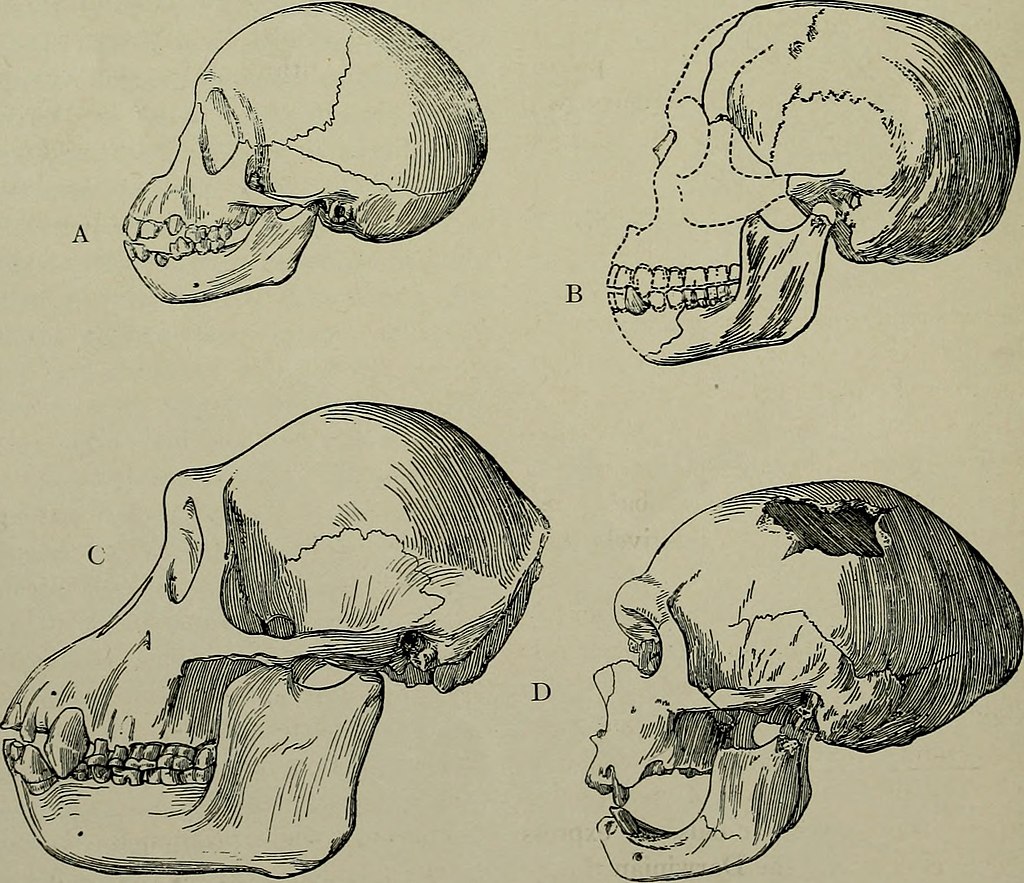

Discovered in 1912 near Piltdown, England, the so-called “Piltdown Man” represents perhaps the most notorious fossil fraud in scientific history. The find consisted of skull fragments and a jawbone that appeared to be the “missing link” between apes and humans, complete with a human-like cranium and an ape-like jaw. Prominent British scientists embraced this discovery as evidence that human evolution had occurred primarily in England rather than Africa. For four decades, Piltdown Man remained in textbooks and museum displays until 1953, when modern testing revealed the truth: the skull was human but only a few hundred years old, while the jaw belonged to an orangutan, artificially stained to look ancient. The perpetrator of this elaborate hoax remains debated, though suspicion has fallen on Charles Dawson, the amateur archaeologist who made the “discovery,” possibly motivated by a desire for scientific recognition.

Archaeoraptor: National Geographic’s Embarrassment

In 1999, National Geographic magazine triumphantly announced the discovery of “Archaeoraptor,” a fossil supposedly providing definitive evidence of the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds. Purchased from a Chinese fossil dealer for $80,000, the specimen appeared to show a creature with the tail of a dinosaur and the wings of a bird. The scientific community’s excitement was short-lived, however, when further investigation revealed the specimen was a composite fraud—a clever assembly of unrelated fossils from different species. CT scans showed that pieces from at least two different specimens had been carefully combined and disguised with plaster. The scandal forced National Geographic to publish a humiliating retraction and highlighted the problems with studying fossils acquired through commercial markets rather than properly documented excavations. Ironically, while Archaeoraptor itself was fake, the evolutionary connection it purported to demonstrate was later confirmed through legitimate discoveries.

The “Lying Stones” of Johann Beringer

One of history’s most tragic fossil hoaxes targeted Johann Bartholomew Adam Beringer, a respected 18th-century professor at the University of Würzburg in Germany. Beginning in 1725, Beringer’s students and colleagues, allegedly annoyed by his arrogance, planted fake fossils on Mount Eibelstadt where they knew he would find them. These “Lying Stones” (Lügensteine) featured incredibly detailed carvings of lizards, frogs, spiders, and even celestial objects like comets and stars, all supposedly naturally formed in stone. Beringer was so convinced of their authenticity that he published an elaborate scholarly treatise about his findings in 1726, complete with engravings. When he eventually discovered carved Hebrew letters on some specimens, suspicion finally arose. By the time Beringer realized he had been duped, his reputation was irreparably damaged, and he had spent much of his fortune buying back copies of his book to destroy them. This cautionary tale demonstrates how even skeptical scientists can fall victim to confirmation bias when presented with “evidence” that supports their existing theories.

Shinichi Fujimura: The “God Hand” Archaeologist

For decades, Shinichi Fujimura was considered Japan’s premier archaeologist, discovering increasingly ancient artifacts that repeatedly pushed back the timeline of Japanese civilization. His uncanny ability to find crucial artifacts earned him the nickname “God Hand” among colleagues. In 2000, however, a newspaper published photographs showing Fujimura secretly burying artifacts at a site before “discovering” them the following day during official excavations. The scandal revealed that many of his most significant finds had been planted, including stone tools supposedly from the Early Paleolithic period dating back 600,000 years. Fujimura later admitted to planting artifacts at numerous sites throughout his career, effectively invalidating decades of Japanese archaeological research. His motivation appeared to be a combination of career pressure and nationalist desire to establish Japan’s prehistoric importance. The Fujimura scandal prompted Japanese archaeology to implement stricter methodological controls and underscored how a single individual’s fraud could contaminate an entire field’s understanding.

The Calaveras Skull: A Gold Rush Prank

During California’s Gold Rush era, miners frequently uncovered fossils while digging for precious metals. In 1866, a human skull was reportedly found 130 feet below ground in Calaveras County, embedded in ancient gravel deposits supposedly millions of years old. If genuine, this discovery would have revolutionized the understanding of human origins, suggesting modern humans existed in North America far earlier than previously thought. Prominent geologist Josiah Whitney championed the find, using it to support his theories about human antiquity. However, suspicions quickly arose when locals began whispering about a prank played on Whitney. It eventually emerged that contemporary human remains had been deliberately planted in the mine shaft as a practical joke. Despite this revelation, Whitney refused to acknowledge the deception, and the controversy continued for decades. The Calaveras Skull demonstrates how the desire to make groundbreaking discoveries can sometimes override scientific skepticism, especially when findings align with researchers’ existing hypotheses.

Morocco’s Fossil Factories: Industrial-Scale Deception

Modern fossil fraud has evolved into an industrial enterprise in regions like Morocco, where entire workshops exist dedicated to manufacturing convincing forgeries. These operations often begin with genuine but common fossils, which craftsmen enhance, restore, or completely fabricate to increase their commercial value. Using techniques like adding false details with dental tools, artificially coloring specimens, or combining multiple specimens into “perfect” examples, these artisans create fossils that even experts struggle to identify as fraudulent without specialized testing. The economic incentives are clear: a common trilobite might sell for $10, while a rare or spectacular specimen can command thousands. This systematic production of fakes has flooded both tourist markets and legitimate fossil trade channels, creating significant problems for researchers and museums worldwide. What makes this phenomenon particularly problematic is that, unlike one-off hoaxes, these forgeries represent an ongoing contamination of the fossil record that requires constant vigilance from the scientific community.

The Mounting Pressure of Academic Publication

The academic world’s intense “publish or perish” culture has created conditions ripe for fossil fraud in modern times. Researchers face enormous pressure to produce groundbreaking discoveries that will secure grants, promotions, and professional prestige. This pressure sometimes leads to cutting corners, premature announcements, o,r in extreme cases, outright fabrication. Several cases have emerged where promising early-career paleontologists have embellished or manufactured evidence to support spectacular claims about fossil discoveries. One notable example involved manipulated photographs of fossil specimens where features were digitally enhanced to better match the researcher’s hypothesis. Unlike historical hoaxes often perpetrated by outsiders, these modern academic frauds typically involve insiders who understand exactly what evidence would be most compelling to their peers. Such cases highlight the crucial role of peer review, replication attempts, and research transparency in maintaining scientific integrity within highly competitive academic environments.

The Feathered Dinosaur Fraud from China

China’s rich fossil deposits have revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur-bird evolution, but they’ve also spawned a lucrative illegal fossil trade prone to forgery. In 2012, a stunning new species of feathered dinosaur called “Microraptor” with apparent four wings made international headlines before closer examination revealed troubling inconsistencies. Under microscopic analysis, some specimens showed artificially attached feather impressions and composite construction from multiple animals. The forgery technique involved taking genuine fossil fragments, embedding them in slabs of artificial matrix, and then adding fake details. This particular fraud was especially sophisticated because it built upon legitimate scientific discoveries—feathered dinosaurs do indeed exist, making it harder for researchers to immediately dismiss spectacular new examples as implausible. The incident forced major museums and journals to implement stricter authentication protocols for specimens originating from Chinese fossil markets, including detailed provenance documentation and advanced imaging analysis before publication.

The “Paleoscam” Documentary Hoax

In 1999, a documentary titled “The Lost Dinosaurs of Egypt” chronicled the supposed rediscovery of Spinosaurus, one of history’s largest carnivorous dinosaurs, by an American university expedition. The film showed researchers uncovering massive bones in the Egyptian desert with great excitement, apparently validating earlier discoveries from the 1930s that had been destroyed during World War II. However, the investigation revealed that many key scenes had been staged using replica bones planted in the sand before filming. While the expedition was real and did make legitimate discoveries, producers had dramatically enhanced the findings for television through various deceptions. This incident highlighted how media pressure and the popularization of paleontology can sometimes compromise scientific accuracy. The increasing commercial value of dinosaur documentaries has created incentives for filmmakers to manufacture dramatic “discoveries” rather than accurately portraying the typically slow, methodical process of paleontological work, further blurring the line between education and entertainment.

Scientific Methods for Detecting Fossil Frauds

Modern paleontology employs sophisticated technological approaches to authenticate fossil specimens and detect potential fraud. X-ray fluorescence can reveal chemical compositions inconsistent with genuine fossilization processes, while CT scanning exposes internal structures that forgers typically cannot replicate. Microscopic analysis often reveals tool marks, adhesives, or artificial weathering invisible to the naked eye. Carbon dating and other radiometric techniques provide chronological verification for specimens purported to be of a certain age. Additionally, geological and taphonomic context—how a fossil relates to its surrounding rock matrix and other nearby specimens—provides crucial authentication evidence that isolated specimens lack. The development of these authentication techniques represents a scientific arms race against increasingly sophisticated forgeries. Many major research institutions now maintain dedicated authentication laboratories specifically to verify significant specimens before publication or acquisition, demonstrating how detecting fraud has become an essential component of modern paleontological practice.

How Fossil Fraud Damages Scientific Progress

The consequences of fossil forgeries extend far beyond embarrassment for duped researchers. When fraudulent specimens enter the scientific literature, they create ripple effects throughout multiple fields of study. Evolutionary biologists may develop theories based on nonexistent transitional forms, while geologists might misinterpret the fossil record’s timeline. Students learn incorrect information that may persist for generations, as textbook revisions lag behind scientific corrections. Research funding gets misdirected toward investigations built on fraudulent foundations, wasting limited resources. Perhaps most damagingly, widely publicized fossil frauds undermine public trust in paleontology and science more broadly, providing ammunition for science deniers and conspiracy theorists. The Piltdown Man hoax, for instance, is still cited by some creationists as evidence that evolutionary theory lacks credibility, even though scientists themselves uncovered the fraud. These cascading impacts explain why the scientific community has developed increasingly rigorous authentication protocols and why exposing fossil fraud is considered essential to maintaining scientific integrity.

Lessons Learned: Strengthening Scientific Verification

Each major fossil fraud has ultimately strengthened scientific methodology by exposing weaknesses in verification procedures. Following the Piltdown Man scandal, physical anthropologists developed more rigorous comparative anatomical standards and began routinely applying chemical tests to significant specimens. The Archaeoraptor embarrassment led many journals to require comprehensive CT scanning of important fossil specimens before publication, while also prompting stricter policies regarding specimens without clear provenance documentation. Today, most reputable museums and research institutions maintain detailed acquisition policies that reject specimens with suspicious or unclear origins, regardless of their apparent scientific value. The scientific community has also embraced technological solutions, creating digital repositories where raw data and high-resolution images of specimens can be examined by researchers worldwide, enabling broader scrutiny. Perhaps most importantly, the culture of paleontology has evolved to value skepticism and verification as much as discovery itself, recognizing that extraordinary claims truly do require extraordinary evidence.

Conclusion

The history of fake fossils serves as a compelling reminder that scientific progress isn’t always linear or straightforward. Each major forgery scandal has prompted important methodological improvements, strengthening the field’s ability to separate fact from fiction. While modern technology has made fraud detection more sophisticated, it has simultaneously enabled more convincing forgeries. This ongoing tension illustrates science’s self-correcting nature—mistakes and deceptions eventually come to light through persistent questioning and improved methods. As paleontology continues advancing our understanding of Earth’s ancient past, the lessons learned from these famous frauds remain relevant, reminding researchers that skepticism, verification, and transparency form the bedrock of scientific credibility.