For decades, our understanding of dinosaurs came primarily from their skeletal remains, giving us insights into their physical characteristics but leaving many behavioral questions unanswered. In recent years, however, a revolution has been quietly taking place in paleontology through the study of fossilized burrows. These preserved tunnels and chambers, created by dinosaurs and their contemporaries, are opening new windows into prehistoric behaviors that bones alone could never reveal. From nesting habits to social structures and survival strategies, fossilized burrows are fundamentally changing our perception of how dinosaurs lived, interacted with their environments, and cared for their young.

The Evolution of Dinosaur Paleontology

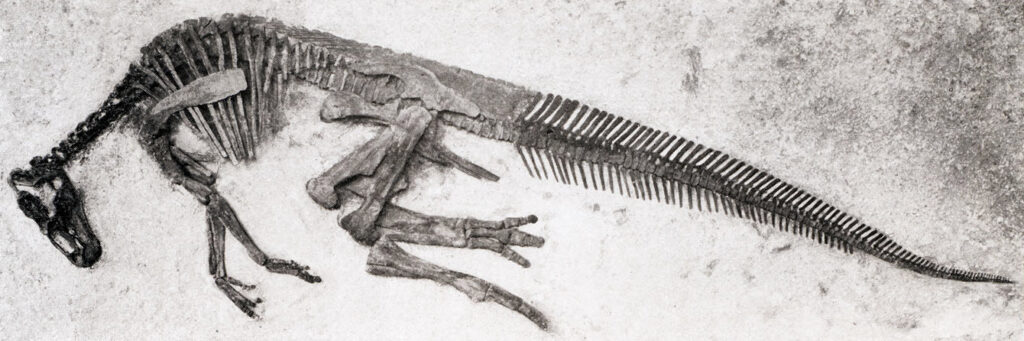

Traditional paleontology has relied heavily on bone preservation to reconstruct dinosaur anatomy and, to a limited extent, behavior. Skeletal remains can tell us about a dinosaur’s size, diet, and movement capabilities, but they provide little direct evidence about how these creatures actually lived their daily lives. The field has progressed significantly from the early days when dinosaurs were portrayed as lumbering, cold-blooded reptiles to our modern understanding of them as dynamic, diverse, and often bird-like animals. This shift in perception has been driven not just by better skeletal analysis but increasingly by the study of trace fossils—preserved evidence of animal activity, including trackways, eggs, nests, and crucially, burrows. These trace fossils capture moments in time when dinosaurs were alive and engaged in specific behaviors, offering insights that skeletal remains simply cannot provide.

What Constitutes a Fossilized Burrow?

Fossilized burrows are preserved underground structures created by animals for shelter, nesting, or protection. Unlike body fossils that preserve the actual remains of an organism, burrows are a type of trace fossil that preserves evidence of animal behavior. When an animal creates a burrow, the disruption in soil layering and the distinctive packing of walls can become preserved when the burrow is filled with sediment that differs from the surrounding material. Paleontologists identify these structures based on their distinct morphology—typically cylindrical or elliptical tunnels with characteristic branching patterns and terminal chambers. The process of fossilization occurs when these burrows are filled with sediment that later hardens, creating what scientists call a “cast” of the original space. In some extraordinary cases, the remains of the burrow creator may be found inside, providing a direct link between the animal and its behavioral footprint.

The Oryctodromeus Discovery: A Game Changer

In 2007, paleontologists made a groundbreaking discovery in Montana that would fundamentally alter our understanding of dinosaur behavior. They uncovered the remains of an adult Oryctodromeus cubicularis, a small plant-eating dinosaur, alongside two juveniles inside what appeared to be a fossilized burrow. This remarkable find provided the first definitive evidence that some dinosaurs actively created burrows and used them as shelters. The name Oryctodromeus itself means “digging runner,” reflecting this newfound behavioral trait. The burrow extended nearly seven feet horizontally into an ancient soil layer and contained a terminal chamber where the dinosaur remains were found. This discovery was particularly significant because it demonstrated not only burrowing behavior but suggested parental care, as the adult was apparently sheltering with its young. The Oryctodromeus find opened the floodgates for reexamining previously discovered fossils and interpreting new finds through the lens of possible burrowing behaviors.

Dinosaur Parenting: Evidence from Underground

Fossilized burrows have substantially altered our understanding of dinosaur parenting and reproductive strategies. Beyond the Oryctodromeus discovery, other evidence from burrows suggests that parental care was more widespread among dinosaurs than previously thought. In the Gobi Desert, researchers have found multiple examples of oviraptorid dinosaurs preserved while sitting on nests, with their limbs arranged in a manner suggesting they were protecting eggs or young in burrow-like structures. More recently, fossilized burrows attributed to small ornithopod dinosaurs have been found containing remains of both adults and juveniles of varying ages, suggesting extended family care within protected underground environments. These findings contradict earlier assumptions that most dinosaurs simply laid eggs and abandoned their offspring. Instead, the evidence from burrows points to complex parenting behaviors more similar to modern birds than to reptiles, reinforcing the evolutionary connection between dinosaurs and their avian descendants.

Climate Adaptation Through Burrowing

One of the most significant insights from fossilized burrows concerns how dinosaurs adapted to challenging environmental conditions. Burrows provide natural insulation against temperature extremes, offering protection from both scorching heat and freezing cold. Paleontologists have discovered dinosaur burrows in fossil layers representing ancient polar regions, suggesting that some species remained in high-latitude environments year-round rather than migrating seasonally as previously assumed. For instance, burrows attributed to small ornithopods have been found in ancient polar environments in both Australia and Antarctica, regions that would have experienced months of darkness and cold temperatures during winter. The construction of these burrows indicates that rather than leaving these harsh environments, some dinosaur species evolved behavioral adaptations to survive in place. This realization has forced scientists to reconsider dinosaur physiology and metabolism, suggesting that even without the benefit of internal temperature regulation like mammals, dinosaurs could exploit microhabitats to survive in extreme climates.

Burrowing as Predator Avoidance

Fossilized burrows have revealed that underground shelters served as crucial defense mechanisms against predators for many smaller dinosaur species. The narrow entrances of most discovered dinosaur burrows would have prevented larger predators from following potential prey into these safe havens. This revelation helps explain how smaller dinosaur species could coexist in ecosystems dominated by massive predators like Tyrannosaurus rex and other large theropods. Interestingly, some fossilized burrows show evidence of having multiple entrances and complex internal networks, similar to those created by modern prey animals seeking to maintain escape routes. Researchers have also noted that many dinosaur burrows discovered to date are attributed to herbivorous species rather than carnivores, suggesting a division in survival strategies between predator and prey. The distribution of these burrows in ancient landscapes also indicates that some dinosaur species may have created “burrow neighborhoods,” potentially providing safety in numbers and contributing to more complex social structures than previously recognized.

Identifying the Burrow Creators

One of the greatest challenges in studying fossilized burrows is confidently identifying which species created them when no remains are preserved inside. Paleontologists employ several techniques to connect burrows to their potential dinosaur architects. Foremost among these methods is analyzing the dimensions and architecture of the burrow in relation to known dinosaur species from the same geological formation and time period. The size of the burrow entrance and tunnels can indicate the approximate size of the creator, while specialized features may correspond to specific anatomical adaptations. For instance, some burrows show distinctive scratch marks that can be matched to the claws of certain dinosaur species. Additionally, scientists look for modifications in limb bones that might indicate digging capabilities, such as robust forelimbs with strong muscle attachment sites. Through these analytical approaches, researchers have identified several dinosaur groups as likely burrowers, including certain ornithopods, small ceratopsians, and some theropods, dramatically expanding our understanding of which dinosaurs engaged in this behavior.

The Unexpected Burrowers: Beyond Small Dinosaurs

While early discoveries focused on smaller dinosaur species, recent findings suggest that burrowing behavior may have been more widespread across various dinosaur groups than initially thought. Paleontologists working in the Cretaceous beds of Mongolia have discovered evidence suggesting that even some medium-sized dinosaurs may have created or utilized burrows. Particularly intriguing are indications that certain protoceratopsians, distant relatives of the famous Triceratops, may have used burrows for nesting or sheltering young. These findings challenge the assumption that burrowing was limited to dinosaurs of rabbit or dog size. Additionally, some research suggests that juvenile specimens of larger dinosaur species might have utilized burrows during their vulnerable early years before outgrowing this behavior as adults. This pattern mirrors that seen in some modern animals like tortoises, which are more prone to burrowing when young. The expanding evidence of burrowing across diverse dinosaur lineages indicates that this behavior evolved independently multiple times, representing a successful adaptation strategy throughout dinosaur evolution.

Technological Advances in Burrow Identification

Modern technology has revolutionized how paleontologists identify and study fossilized burrows, leading to a surge in new discoveries. Ground-penetrating radar has become an invaluable tool, allowing researchers to detect subsurface anomalies that might represent preserved burrow systems without destructive excavation. Once identified, CT scanning technology enables scientists to create detailed three-dimensional models of burrow structures, revealing internal architecture that would be impossible to study using traditional methods. These 3D models can then be analyzed using engineering principles to test hypotheses about the burrow’s structural integrity and the behaviors of its creators. Advanced sediment analysis techniques, including micromorphology, allow researchers to examine the microscopic structure of burrow walls, identifying subtle traces such as claw marks or body impressions that might otherwise go unnoticed. Geochemical analysis of burrow fills can also reveal information about the ancient environment and potentially identify organic residues left behind by the burrow’s inhabitants, further connecting these structures to specific dinosaur species.

Social Behavior Insights from Communal Burrows

Some of the most intriguing fossilized burrows show evidence of communal use, dramatically altering our understanding of dinosaur social structures. In Montana and Alberta, paleontologists have discovered complex burrow systems with multiple chambers that appear to have housed several individuals simultaneously. These findings suggest that at least some dinosaur species lived in family groups or small colonies, similar to modern burrowing animals like prairie dogs or meerkats. The architecture of these communal burrows often includes specialized chambers that may have served different functions, such as nesting areas, food storage, or waste disposal, indicating sophisticated social organization. In Australia, researchers have found evidence of what appears to be a dinosaur “nursery burrow” containing juvenile remains of different ages, suggesting that some species may have shared childcare responsibilities within their communities. These discoveries of communal living arrangements have prompted paleontologists to reconsider earlier assumptions about dinosaur intelligence and social complexity, suggesting that some species may have had more advanced social behaviors than previously credited.

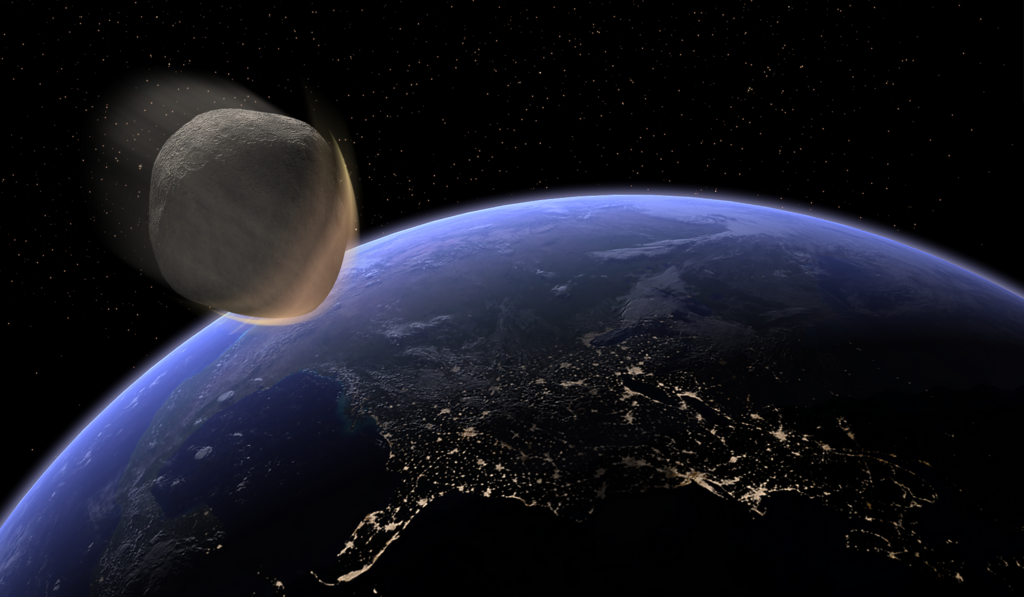

Burrows as Survival Mechanisms During Extinction Events

Perhaps one of the most profound insights from the study of fossilized burrows concerns their potential role during extinction events. The ability to retreat underground may have provided critical protection during catastrophic environmental changes, including the asteroid impact that marked the end of the Cretaceous period. Burrows would have offered shelter from immediate effects such as thermal radiation, wildfires, and impact debris, as well as subsequent challenges like acid rain and dramatic temperature fluctuations. Mathematical models suggest that even a relatively shallow burrow could have provided sufficient insulation to survive the initial temperature spike following the Chicxulub impact. While non-avian dinosaurs ultimately went extinct, their burrowing contemporaries—including mammals, lizards, and amphibians—had much higher survival rates. This pattern has led some paleontologists to speculate that if more dinosaur species had evolved burrowing behaviors, the outcome of the extinction event might have been different. The study of these preserved burrows thus provides crucial context for understanding not just how dinosaurs lived, but potentially why certain lineages perished while others survived.

Comparing Dinosaur Burrows to Modern Animal Analogs

To better understand ancient dinosaur burrows, paleontologists frequently draw comparisons with the burrowing behaviors of modern animals. The burrows of present-day creatures like wombats, prairie dogs, and gopher tortoises offer valuable behavioral models for interpreting prehistoric structures. For instance, the complex, multi-chambered burrow systems created by prairie dogs bear striking similarities to some fossilized dinosaur burrows, suggesting comparable social organizations. Similarly, the way modern wombats create burrows with multiple entrances for predator avoidance likely mirrors strategies employed by certain burrowing dinosaurs. The depth and angle of burrow entrances in modern species also provide insights into how dinosaurs might have designed their shelters to manage temperature, humidity, and flooding risks. Particularly illuminating are the burrows created by contemporary burrowing birds like puffins and some penguin species, which may represent the closest living analogs given the evolutionary relationship between birds and dinosaurs. These comparative studies allow paleontologists to make more confident inferences about dinosaur behavior based on the observed patterns and adaptations in their modern-day ecological counterparts.

Future Frontiers in Burrow Paleontology

The study of fossilized dinosaur burrows remains a relatively young field with tremendous potential for future discoveries. As awareness of these structures increases among paleontologists worldwide, identification of previously overlooked burrows in existing fossil collections is likely to accelerate. New excavation techniques specifically designed to preserve the delicate structures of burrows are being developed, potentially yielding more complete specimens with better contextual information. Emerging technologies like portable X-ray fluorescence might soon allow field identification of chemical signatures associated with burrow structures, making detection more efficient. Promising research directions include investigating potential seasonal variations in burrow use through isotope analysis and examining how burrowing behaviors may have differed across various paleoenvironments and climates. Perhaps most excitingly, as more dinosaur taxa are associated with burrowing behaviors, comprehensive evolutionary analyses may reveal patterns in how this adaptation emerged across different lineages, potentially uncovering new connections between dinosaur groups previously considered unrelated. The continued study of these remarkable structures promises to further transform our understanding of dinosaur behavior, physiology, and evolutionary history in the coming decades.

In conclusion, fossilized burrows have emerged as revolutionary windows into dinosaur behavior, challenging long-held assumptions and providing unprecedented insights into how these fascinating creatures actually lived. From revealing complex parenting strategies and social structures to documenting climate adaptations and survival mechanisms, these preserved tunnels and chambers tell stories that bones alone never could. As technology advances and more researchers turn their attention to these often-overlooked trace fossils, our understanding of dinosaur behavior continues to evolve dramatically. The humble burrow, once barely considered in dinosaur studies, now stands as a testament to the remarkable behavioral complexity of these ancient animals, reminding us that there is still much to discover about Earth’s most famous prehistoric inhabitants.