In the vast network of museum collections worldwide, millions of precious fossils lie carefully preserved – yet many remain unstudied and essentially lost to science for decades or even centuries. Behind the gleaming public exhibits that draw visitors, museums house enormous research collections in their basement storage areas, containing specimens that often outnumber displayed items by factors of hundreds or thousands. These repositories hold countless untold stories of prehistoric life, with many significant discoveries hiding in plain sight, waiting for the right researcher to recognize their importance. The phenomenon of “lost” fossils represents a fascinating intersection of institutional history, scientific prioritization, and the sheer overwhelming volume of our natural heritage collections.

The Sheer Scale of Museum Collections

Most natural history museums display only a tiny fraction of their total holdings, with estimates suggesting that less than 1% of specimens ever make it to public view. The American Museum of Natural History in New York, for example, houses approximately 33 million specimens and artifacts, while London’s Natural History Museum maintains around 80 million items in its collections. These massive numbers create inevitable backlogs in cataloging, with some institutions housing hundreds of thousands of specimens that remain in their original field jackets – the protective plaster or burlap coverings applied during excavation. Without sufficient staff to process these materials, fossils can remain wrapped and untouched for generations, their scientific significance unknown and inaccessible. The sheer volume presents both a tremendous scientific resource and a daunting logistical challenge that contributes directly to the “lost fossil” phenomenon.

Historical Collection Practices and Documentation Issues

Many museum collections began in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when documentation standards differed dramatically from today’s rigorous protocols. Early fossil collectors sometimes recorded minimal information about their finds, perhaps noting only a general region or formation rather than precise geographic coordinates. Paper records from these expeditions may have deteriorated, been lost in institutional moves, or simply become separated from the specimens they described. Some historical collections arrived at museums through donations from wealthy amateur collectors who maintained their idiosyncratic cataloging systems, further complicating matters. In the notorious “Bone Wars” of the late 1800s, paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh collected fossils at such a frenzied pace that proper documentation was often sacrificed in the rush to claim discoveries. These historical documentation challenges mean that even when specimens are physically present in collections, their contextual information, crucial for scientific value, may be effectively lost.

Institutional Mergers and Relocations

Throughout museum history, collections have frequently changed hands through institutional mergers, university departmental reorganizations, or complete facility relocations. During these transitions, careful tracking of every specimen becomes extraordinarily difficult, particularly for smaller or less spectacular items. When the University of California Museum of Paleontology consolidated collections from various campus departments in the 1960s, thousands of specimens needed rehousing and recataloging, a process that took decades to complete. Similarly, when natural history collections moved from the British Museum to the newly established Natural History Museum in London in the 1880s, the massive transfer operation inevitably resulted in some specimens becoming temporarily “lost” in the system. These institutional disruptions, while necessary for long-term preservation, create periods of vulnerability where specimens may be misplaced or their documentation separated from the physical items, leading to decades of obscurity until rediscovery.

Storage System Evolution and Reorganization

Museum storage systems have evolved dramatically over the centuries, from simple wooden cabinets to sophisticated compactor systems with climate control. When collections transition between storage methods, specimens can be misplaced or incorrectly categorized within the new system. A fossil initially stored by geographic location might later be reorganized taxonomically, creating opportunities for items to be filed in unexpected locations. Some institutions have undergone multiple complete reorganizations of their collections, with each transition introducing potential for specimens to become “lost” within the system. The Field Museum in Chicago, for instance, has moved many collections multiple times throughout its history, including a major relocation from the World’s Columbian Exposition buildings to its current location. During such transitions, smaller or less remarkable specimens may be temporarily shelved in temporary locations and then forgotten, becoming effectively invisible until storage areas undergo a rough inventory decades later.

Taxonomic Reclassification Challenges

The science of taxonomy continuously evolves as researchers gain new insights into evolutionary relationships, sometimes dramatically reshuffling how we classify organisms. A fossil originally identified and cataloged as belonging to one taxonomic group might later be recognized as belonging to another entirely, creating a disconnect between its physical location in storage and its listing in catalogs. Museum databases may not always be promptly updated to reflect these scientific reclassifications, particularly for specimens that haven’t been studied in decades. When the dinosaur formerly known as Brontosaurus was reclassified as Apatosaurus in the early 20th century (before being reinstated as a valid genus in 2015), museums worldwide had to reconsider how their specimens were labeled and stored. These taxonomic shifts can effectively “hide” specimens within collections when researchers search catalogs using current scientific names without realizing that specimens might be filed under outdated classifications.

The Impact of Staff Turnover and Lost Knowledge

Museum collections depend heavily on the institutional knowledge carried by long-term staff members who develop intimate familiarity with storage locations and collection histories. When these individuals retire or leave without adequate knowledge transfer to successors, crucial information about the collection organization can disappear. A curator who knows that “the Morrison Formation mammals are actually in Cabinet 47B, not 32A, where they’re supposed to be” takes that practical knowledge when they depart unless it’s properly documented. Many museums have experienced periods of reduced staffing or budget constraints that eliminated positions, creating gaps in the human chain of collection knowledge. This institutional memory loss compounds over decades, with each generation of staff potentially losing track of certain specimens or special storage arrangements that deviated from standard protocols, effectively rendering some fossils “lost” even though they remain physically present in the collection.

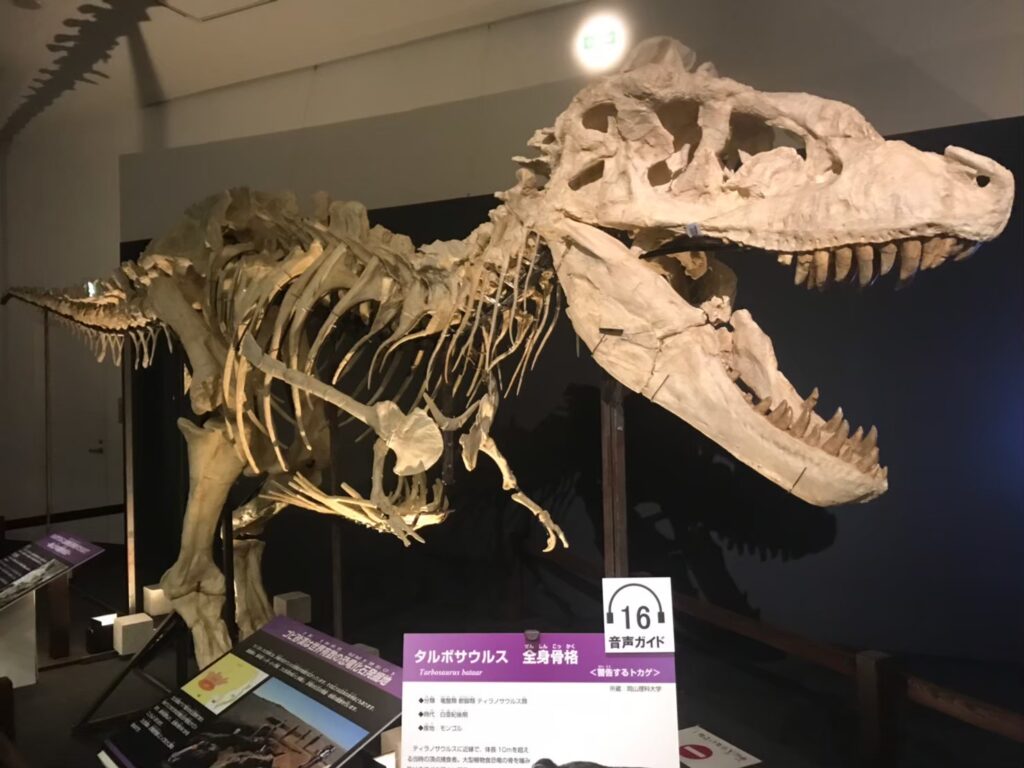

Prioritization of “Showpiece” Specimens

Museums naturally devote more immediate attention to spectacular, complete, or particularly rare specimens that make compelling public displays or represent significant scientific breakthroughs. This practical prioritization means that less visually impressive fossils often receive delayed processing and study, sometimes waiting decades in storage before receiving scholarly attention. A complete Tyrannosaurus skull will understandably receive immediate conservation attention and research priority over boxes of fragmentary fossil turtle shells or partial fish specimens. Yet historically, these overlooked “minor” specimens have occasionally yielded major scientific insights when finally examined by specialists with the right expertise. The small, unassuming fossils that first demonstrated dinosaur endothermy (warm-bloodedness) sat in collections for years before their significance was recognized, illustrating how scientific importance doesn’t always correlate with immediate visual appeal. This necessary but imperfect prioritization system contributes significantly to the phenomenon of scientifically valuable fossils remaining effectively “lost” in storage for extended periods.

Limited Specialist Expertise for Identification

Many fossil groups require highly specialized knowledge for proper identification and scientific assessment, yet the number of experts in particular taxonomic groups may be extremely limited worldwide. A museum might house significant specimens of certain fossil invertebrates, plants, or microorganisms, but without access to the handful of global specialists who could recognize their importance, these items remain effectively “lost” to science. For example, conodonts – microscopic tooth-like fossils crucial for dating certain rock formations – require such specialized expertise that collections may wait decades for visiting specialists to examine them properly. Similarly, fossil pollen, diatoms, and many invertebrate groups have relatively few dedicated researchers compared to more charismatic groups like dinosaurs and mammals. This expertise bottleneck means that even well-cataloged specimens may remain scientifically “invisible” until the right specialist happens to visit that particular institution or specific collection, a chance occurrence that might take decades to transpire.

The Digital Cataloging Revolution and Its Limitations

The transition from paper card catalogs to computerized databases represents a revolutionary improvement in specimen tracking, but this massive undertaking remains incomplete at many institutions. Digitizing millions of handwritten records is extraordinarily time-consuming, requiring careful transcription and verification to avoid introducing new errors during the process. Many museums have prioritized digitizing records for certain collections, while others remain accessible only through traditional card catalogs or ledger books, creating an uneven landscape of discoverability. The Yale Peabody Museum, like many institutions, has engaged in multi-year projects to digitize its massive collections, but complete digital conversion of all records remains an ongoing challenge across the museum world. Even sophisticated database systems can’t resolve fundamental issues with incomplete original documentation or specimens that were never properly cataloged when they first entered collections. Digital tools represent powerful solutions to many aspects of the “lost fossil” problem, but their implementation remains a work in progress that will likely take decades to fully realize.

Storage Space Constraints and Temporary Solutions

Museums frequently face severe space limitations that necessitate creative storage solutions, sometimes leading to specimens being placed in temporary or makeshift locations that become permanent by default. As collections continuously grow through new field expeditions and donations, storage areas become increasingly crowded, occasionally forcing curators to utilize corridor spaces, offices, or other non-standard storage areas. These temporary solutions, implemented during space crises, may be poorly documented in formal systems, particularly if they were intended as short-term measures. A fossil temporarily stored “behind Cabinet B until we can process the new Madagascar collection” might remain there for decades if the expected permanent storage solution never materializes due to budget constraints. These space compromises, while practical necessities, create situations where specimens effectively disappear from institutional awareness until comprehensive inventories or facility renovations eventually bring them back to light.

Famous Cases of “Rediscovered” Fossils

The scientific literature contains numerous dramatic examples of significant fossils “rediscovered” in museum collections after decades of obscurity. Perhaps most famously, the holotype specimen of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus – a massive carnivorous dinosaur larger than Tyrannosaurus rex – was discovered in Egypt in 1912 and housed in Munich’s paleontological museum, only to be destroyed during Allied bombing in World War II. For decades, paleontologists believed all evidence of this remarkable dinosaur was lost, until researcher Nizar Ibrahim tracked down additional Spinosaurus material in the collections of the Natural History Museum in Milan that had been collected in the 1930s but never properly studied. Similarly, the earliest known bird specimens from the Jurassic period of China sat misidentified in Chinese museum collections for years before their true significance was recognized. These high-profile rediscoveries represent just the most dramatic examples of a phenomenon that occurs regularly in museums worldwide, as researchers continuously uncover specimens that have been effectively “hiding in plain sight” within institutional collections.

Budget Constraints and Staffing Limitations

Perhaps the most fundamental driver of the “lost fossil” phenomenon is the chronic underfunding that affects museums worldwide, limiting their ability to maintain adequate professional staff for collection management. Processing new specimens properly requires significant time from trained personnel – measuring, photographing, cataloging, and properly housing each item according to conservation standards. When budget constraints force museums to operate with minimal staff, enormous backlogs inevitably develop. The Carnegie Museum of Natural History, like many institutions, has experienced periods where multiple full-time collection manager positions remained unfilled due to financial constraints, creating situations where new material entering collections could not be processed promptly. Without sufficient professional staff dedicated to collection management, even well-organized museums struggle to maintain perfect awareness of their holdings, particularly for historical collections acquired decades or centuries earlier. This fundamental resource limitation underpins many of the specific mechanisms by which fossils become temporarily “lost” within institutional collections.

The Future: Modern Solutions to Historical Problems

Museums are increasingly implementing innovative solutions to address the historical challenges that have led to “lost” specimens. Modern collection management now frequently includes comprehensive inventory projects, sometimes using teams of trained volunteers to systematically examine every drawer and cabinet in massive storage areas. Barcoding systems, similar to those used in retail inventory management, allow more reliable tracking of specimens throughout institutions. Three-dimensional scanning technology enables museums to create digital records of specimens’ physical characteristics, providing valuable reference points for identification even if items become temporarily misplaced. Open-access database projects like iDigBio (Integrated Digitized Biocollections) are creating centralized, searchable resources that make specimen data available globally, increasing the likelihood that researchers will discover relevant material in distant collections. While the enormous scale of natural history collections ensures that some specimens will always be awaiting “rediscovery,” these technological and methodological advances are gradually reducing the scale of the problem and bringing more of our preserved natural heritage into scientific accessibility.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of fossils becoming “lost” in museum collections represents not negligence but rather the inevitable consequence of institutions tasked with preserving millions of specimens across centuries with limited resources. These temporarily misplaced treasures continue to yield significant scientific discoveries when rediscovered, demonstrating the enduring value of museum collections as repositories of knowledge waiting to be unlocked. As digitization efforts continue and collection management practices evolve, we can expect more “forgotten” specimens to emerge from the shadows, potentially revolutionizing our understanding of prehistoric life. The next breakthrough in paleontology may well come not from a dramatic new field discovery but from a careful researcher opening a drawer in a museum basement, finding a specimen that has been patiently waiting decades for its scientific significance to be recognized.