Imagine opening your morning newspaper in 1841 and reading about colossal beasts that once ruled the Earth, creatures so massive they could crush a horse under their feet. For Victorian society, accustomed to a world where the largest land animals were elephants and rhinos, the very notion of dinosaurs shattered everything they thought they knew about life on Earth. The discovery of these ancient giants didn’t just revolutionize science—it sent shockwaves through churches, sparked heated debates in parlors, and ignited the public imagination in ways that still echo today.

The Fossil Hunters Who Changed Everything

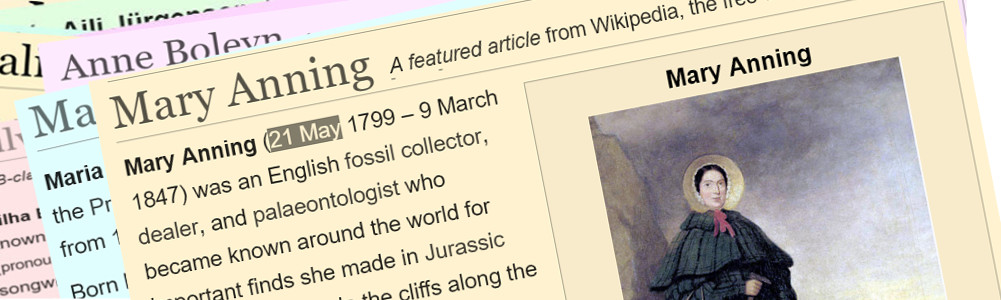

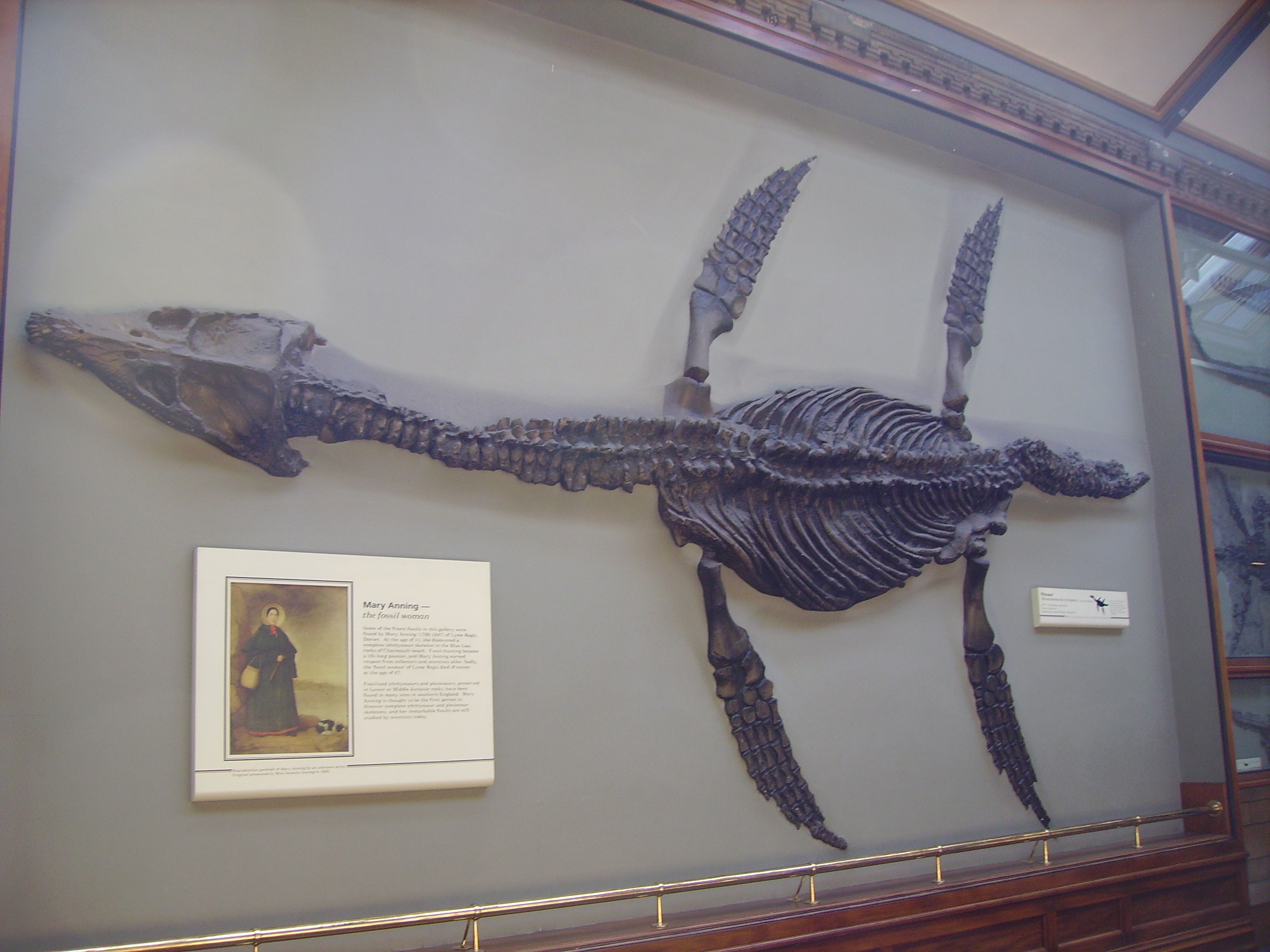

Mary Anning walked the treacherous cliffs of Lyme Regis with nothing but a keen eye and relentless determination, but her discoveries would topple centuries of scientific understanding. When she unearthed the first complete ichthyosaur at just eleven years old, she had no idea she was about to transform how humanity viewed its place in history. The fossil, with its massive eye socket and rows of sharp teeth, looked like something from a nightmare rather than nature.

Gideon Mantell, a country doctor with an obsession for fossils, stumbled upon teeth so large they defied explanation in 1822. His wife Mary reportedly found the first specimens during a routine walk, though this story has been debated by historians. These teeth, later identified as belonging to Iguanodon, were unlike anything in the known animal kingdom—massive, leaf-shaped, and clearly designed for a herbivorous giant.

The scientific community initially dismissed these discoveries as anomalies or misidentified remains of known animals. However, as more evidence accumulated, skeptics found themselves facing an uncomfortable truth: Earth had once been home to creatures that dwarfed anything in their contemporary world.

When Science Collided with Scripture

The revelation of dinosaurs struck at the heart of Victorian religious beliefs like a theological earthquake. For centuries, the Bible had provided a comfortable timeline of Earth’s history, suggesting a world created just 6,000 years ago with all species perfectly formed by divine hand. Suddenly, here were creatures that clearly predated human civilization by millions of years, their very existence challenging the literal interpretation of Genesis.

Church leaders found themselves in an impossible position, torn between mounting scientific evidence and fundamental religious doctrine. Some clergy attempted to reconcile dinosaurs with scripture by suggesting they were victims of Noah’s flood, while others argued they were God’s failed experiments before creating the perfect world described in the Bible. The most progressive religious thinkers began to embrace what would become known as “gap theory”—the idea that vast ages existed between the biblical verses of Genesis.

This theological crisis wasn’t confined to church walls; it invaded family dinners and social gatherings across Britain and America. Children who had learned about Adam and Eve naming all the animals suddenly wondered why dinosaurs weren’t mentioned in their Sunday school lessons.

The Great Bone Wars Begin

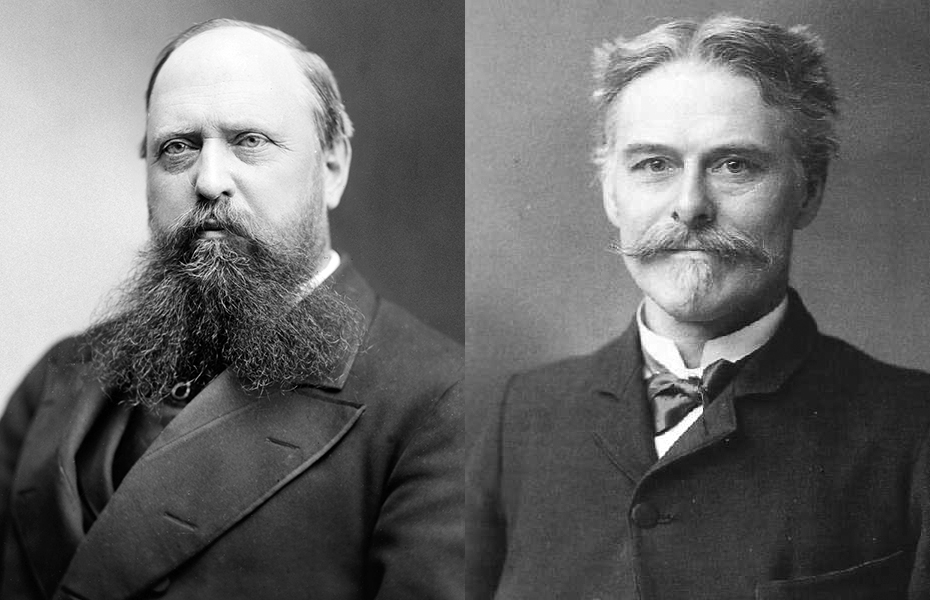

Nothing captures the public’s fascination with dinosaurs quite like the bitter rivalry between Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope, two brilliant paleontologists who turned fossil hunting into a blood sport. Their feud, which began in the 1870s, involved espionage, sabotage, and even dynamite attacks on fossil sites. Newspapers eagerly covered their exploits, transforming scientific discovery into entertainment that rivaled any adventure novel.

The competition between these men pushed the boundaries of what was scientifically possible, leading to the discovery of iconic dinosaurs like Stegosaurus, Triceratops, and Allosaurus. Their rivalry also had a darker side—rushed publications, incomplete reconstructions, and bitter personal attacks that damaged both men’s reputations. Yet the public ate up every sensational detail, from Cope’s dramatic reconstructions to Marsh’s secretive excavations.

This period established dinosaurs as symbols of American scientific achievement and natural wonder. The fact that some of the world’s most impressive dinosaur fossils were being unearthed in the American West added a sense of national pride to the scientific discoveries, making dinosaurs uniquely American in the public consciousness.

Victorian Society’s Fascination with Giants

![Victorian Society's Fascination with Giants (image credits: [View of Victorian park scene], No restrictions, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=49851828)](https://dino-world.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/1751505032455_28View_of_Victorian_park_scene29_281248353911429.jpg)

The Victorian era was already obsessed with spectacle and wonder, from circus performances to world’s fairs, so dinosaurs arrived at the perfect cultural moment. These ancient beasts satisfied the public’s hunger for the extraordinary while providing scientific legitimacy that distinguished them from mere carnival attractions. Dinosaurs became the ultimate conversation starters at dinner parties, combining intellectual sophistication with thrilling horror.

Middle-class families began collecting fossil replicas and dinosaur illustrations, turning their parlors into miniature museums of prehistoric life. Children’s books featuring dinosaurs became bestsellers, though many depicted the creatures as moral lessons about the consequences of violence and excess. The Victorian obsession with classification and order found perfect expression in dinosaur taxonomy, with each new discovery adding another branch to the tree of ancient life.

Women, traditionally excluded from scientific pursuits, found dinosaurs offered a socially acceptable way to engage with natural history. Fossil collecting became a fashionable hobby for ladies, though their contributions were often minimized or attributed to male relatives.

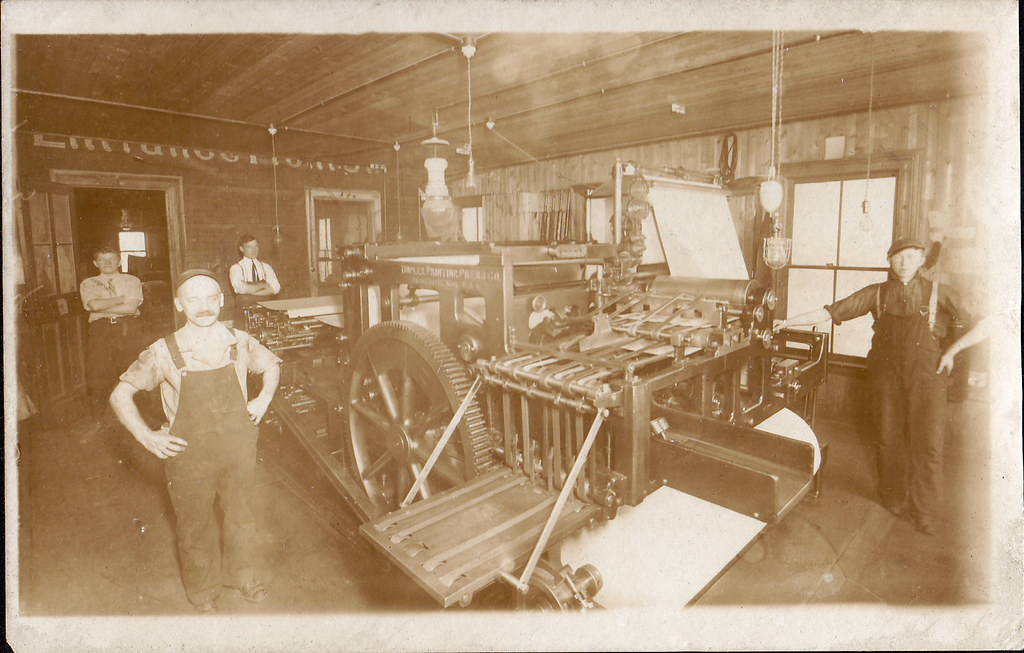

Newspapers Turn Science into Sensation

The press quickly discovered that dinosaurs sold papers like nothing else, transforming dry scientific announcements into breathless adventure stories. Headlines screamed about “Terrible Lizards” and “Monsters of the Ancient World,” often accompanied by sensationalized illustrations that bore little resemblance to scientific accuracy. Journalists, most with no scientific training, freely speculated about dinosaur behavior, creating narratives that were more fiction than fact.

The penny press, aimed at working-class readers, particularly embraced dinosaur stories as affordable entertainment. These publications often portrayed dinosaurs as cautionary tales about the dangers of a world without divine guidance, while simultaneously thrilling readers with descriptions of epic battles between prehistoric titans. The more respectable newspapers struggled to balance scientific accuracy with public interest, often failing at both.

This media coverage established patterns that persist today—the public’s fascination with dinosaur discoveries, the tendency to sensationalize scientific findings, and the challenge of communicating complex paleontological concepts to general audiences. The press coverage also revealed society’s deep ambivalence about scientific progress, celebrating discoveries while simultaneously expressing anxiety about their implications.

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs Spark Controversy

When the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs were unveiled in 1854, they represented the first attempt to bring these ancient creatures to life for public viewing. Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, working with leading paleontologist Richard Owen, created concrete sculptures that were revolutionary for their time, though they look charmingly primitive by modern standards. The project generated enormous public interest, with thousands of visitors flocking to see the prehistoric menagerie.

The sculptures sparked heated debate about scientific accuracy versus public engagement. Critics argued that the reconstructions were too speculative, based on incomplete fossil evidence, while supporters claimed they served valuable educational purposes. The famous dinner party held inside the partially completed Iguanodon model became a symbol of scientific progress and public spectacle, though it also represented the commercialization of paleontology.

Public reaction was mixed but intense—some visitors were thrilled by the opportunity to “see” dinosaurs, while others found the creatures disturbing or blasphemous. Children reportedly had nightmares about the concrete monsters, while adults debated whether such displays were appropriate for family viewing. The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs established the template for modern dinosaur exhibits, balancing scientific education with entertainment value.

Scientific Societies Struggle with Public Interest

The Royal Society and other prestigious scientific institutions found themselves in an uncomfortable position as dinosaur discoveries attracted massive public attention. These organizations, accustomed to conducting research in relative obscurity, suddenly found their meetings packed with curious members of the public eager to hear about the latest fossil finds. The democratic nature of scientific discovery clashed with the elitist traditions of Victorian academic institutions.

Many established scientists worried that public fascination with dinosaurs would reduce paleontology to mere entertainment, undermining the serious scientific work being conducted. They feared that sensationalized media coverage would distort public understanding of evolutionary theory and geological time scales. Some institutions attempted to restrict public access to lectures and exhibitions, while others embraced the educational opportunities presented by widespread interest.

The tension between scientific rigor and public engagement that emerged during this period continues to influence how paleontological discoveries are presented today. The challenge of maintaining scientific accuracy while satisfying public curiosity remains one of the defining features of dinosaur research and exhibition.

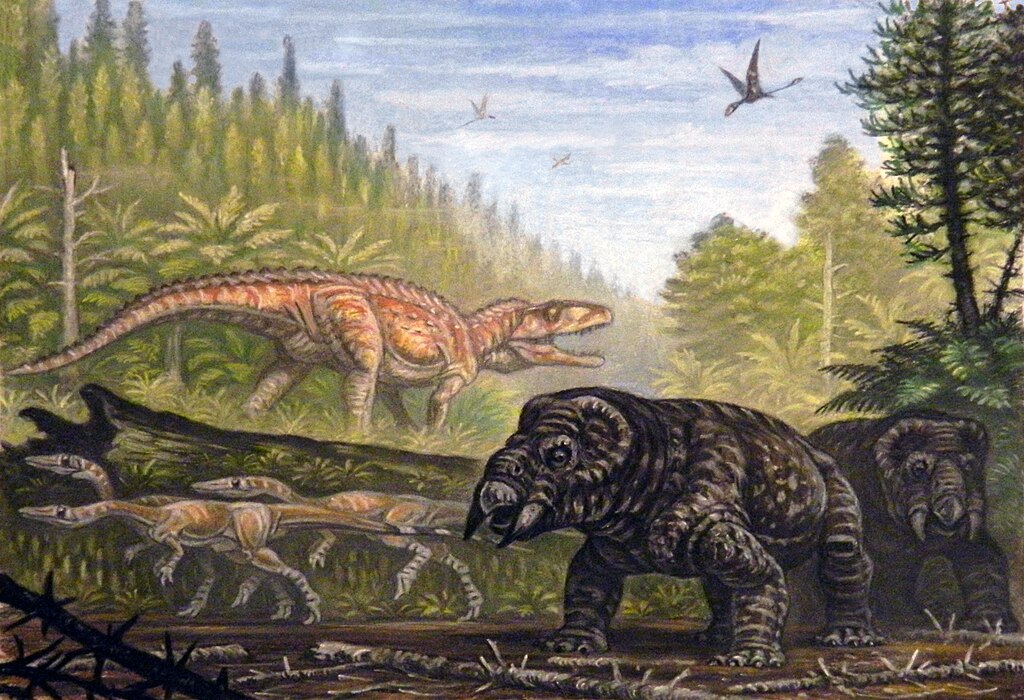

Artists and Illustrators Bring Dinosaurs to Life

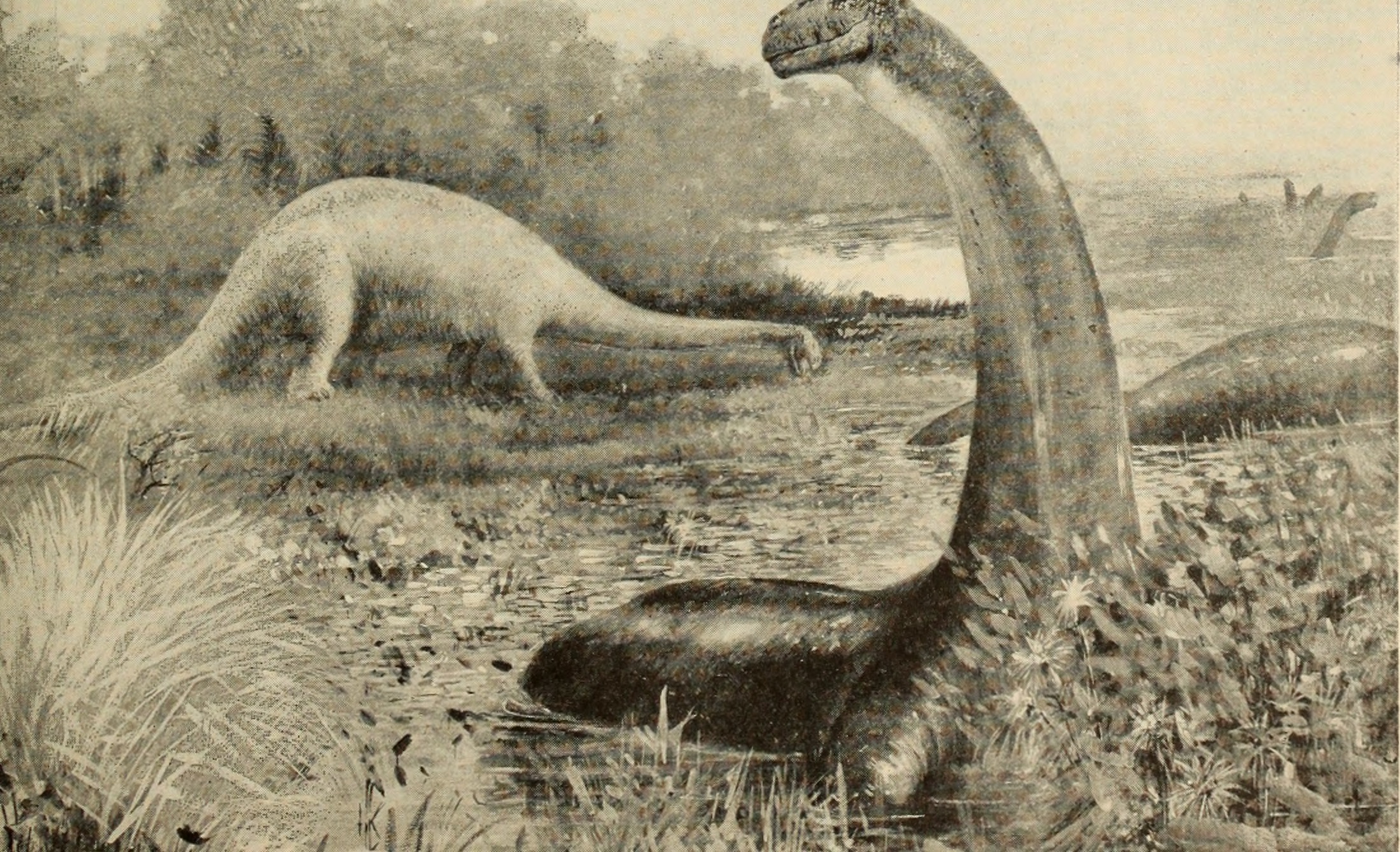

The visual representation of dinosaurs became as important as their scientific description, with artists like Charles Knight pioneering the field of paleoart. These illustrations, often based on limited fossil evidence, shaped public perception of dinosaurs more powerfully than any scientific paper. Knight’s dramatic paintings of dinosaur combat and prehistoric landscapes became iconic images that influenced popular culture for generations.

The challenge facing these artists was immense—how do you accurately depict a creature known only from scattered bones and teeth? Many early illustrations were heavily influenced by contemporary animals, resulting in dinosaurs that resembled oversized lizards or dragons. The artistic choices made during this period, from posture to coloration, became deeply embedded in popular consciousness despite later scientific corrections.

Public reaction to these illustrations was intense and immediate. People who had never seen a fossil could now visualize these ancient creatures, making dinosaurs accessible to mass audiences. The power of these images to capture imagination and communicate scientific concepts established illustration as an essential component of paleontological research and education.

Children’s Literature Embraces Prehistoric Monsters

The emergence of dinosaur-themed children’s literature marked a significant shift in how society viewed these ancient creatures and their place in education. Early children’s books about dinosaurs often portrayed them as moral lessons, with the creatures’ extinction serving as a warning about the consequences of violence and excess. Authors struggled to balance scientific accuracy with age-appropriate content, often erring on the side of sensationalism.

Parents and educators debated whether dinosaur stories were suitable for young minds, with some arguing that tales of prehistoric monsters would frighten children or undermine religious teachings. Others saw dinosaur books as valuable educational tools that could spark interest in natural history and scientific thinking. The popularity of these books among children often overrode adult concerns, establishing dinosaurs as permanent fixtures in children’s literature.

The success of dinosaur-themed children’s books revealed society’s ambivalence about scientific progress and its impact on traditional values. While adults wrestled with the theological implications of dinosaur discoveries, children embraced these creatures with uncomplicated enthusiasm, often knowing more about prehistoric life than their parents and teachers.

The Economic Impact of Dinosaur Mania

The public’s fascination with dinosaurs quickly translated into economic opportunities, creating entirely new industries around fossil collecting, exhibition, and education. Museums began dedicating significant resources to dinosaur displays, recognizing their power to attract visitors and generate revenue. The competition between institutions for the most impressive dinosaur specimens drove up prices for fossils, creating a market that persists today.

Entrepreneurs capitalized on dinosaur mania by producing everything from toy dinosaurs to educational materials, though quality and accuracy varied widely. The commercialization of dinosaurs raised questions about the relationship between scientific research and public entertainment, with some critics arguing that commercial interests were corrupting scientific integrity. Others saw the economic benefits as validation of paleontology’s importance to society.

The development of dinosaur tourism, from fossil hunting expeditions to museum visits, created new forms of educational travel that combined entertainment with learning. This phenomenon established patterns of science-based tourism that continue to thrive today, demonstrating the enduring economic value of public interest in scientific discoveries.

International Reactions and Cultural Differences

While dinosaur discoveries originated primarily in Britain and America, reactions across different cultures revealed fascinating variations in how societies processed these revelations. European countries with strong scientific traditions, like Germany and France, approached dinosaur research with systematic rigor, often criticizing Anglo-American sensationalism. Their public reactions tended to be more measured, focusing on scientific implications rather than popular spectacle.

In Catholic countries, the Church’s response to dinosaur discoveries was more coordinated and cautious than in Protestant nations, with official pronouncements attempting to reconcile paleontological evidence with religious doctrine. Asian countries, encountering dinosaur discoveries later, often integrated these creatures into existing mythological frameworks, seeing them as validation of dragon legends rather than challenges to traditional beliefs.

The global spread of dinosaur knowledge revealed how scientific discoveries could transcend cultural boundaries while being interpreted through local cultural lenses. This international dimension of dinosaur mania helped establish paleontology as a truly global scientific discipline, though cultural differences in interpretation and acceptance persist to this day.

The Role of Women in Early Dinosaur Discovery

Women played crucial but often overlooked roles in early dinosaur discoveries, facing significant barriers to recognition in male-dominated scientific circles. Mary Anning’s contributions to paleontology were revolutionary, yet she struggled for financial security and scientific credit throughout her life. Her discoveries formed the foundation of modern understanding of Mesozoic marine reptiles, though male scientists often claimed credit for her work.

Other women, like Mary Ann Mantell, made significant fossil discoveries but saw their contributions minimized or attributed to male relatives. The Victorian era’s restrictions on women’s participation in scientific societies meant that female fossil hunters operated largely outside official recognition, though their work was essential to the field’s development. Public reaction to women’s involvement in dinosaur discovery was mixed, with some celebrating their contributions while others questioned the appropriateness of women engaging in such activities.

The stories of these pioneering women reveal the complex social dynamics surrounding early paleontology and the ways in which scientific discovery intersected with gender roles and social expectations. Their perseverance in the face of discrimination helped establish precedents for women’s participation in scientific research that continue to influence the field today.

How Dinosaurs Changed Education Forever

The discovery of dinosaurs fundamentally transformed how natural history was taught in schools and universities, forcing educators to grapple with concepts of deep time and extinction that challenged traditional curricula. Teachers found themselves explaining geological time scales that dwarfed human history, while students struggled to comprehend the vast ages involved in dinosaur evolution. The inclusion of dinosaur content in textbooks sparked debates about the balance between scientific accuracy and age-appropriate education.

Universities began establishing paleontology programs to meet growing interest in dinosaur research, creating new academic disciplines and career paths. The interdisciplinary nature of dinosaur studies, combining geology, biology, and anatomy, encouraged more holistic approaches to scientific education. Public lectures about dinosaurs became popular educational events, drawing audiences far beyond traditional academic circles.

The educational impact of dinosaur discoveries extended beyond formal institutions, inspiring the creation of natural history museums and public exhibitions that made scientific knowledge accessible to broader audiences. This democratization of scientific education reflected changing attitudes about the role of science in society and the importance of public understanding of natural history.

The Lasting Legacy of First Encounters

The initial public reaction to dinosaur discoveries established patterns of scientific communication and public engagement that continue to influence how we approach paleontological research today. The combination of scientific rigor and popular fascination that characterized early dinosaur studies created a template for science communication that balances accuracy with accessibility. Modern dinosaur exhibitions and media coverage still reflect the tension between entertainment and education that emerged during the Victorian era.

The theological and philosophical questions raised by dinosaur discoveries continue to resonate in contemporary debates about evolution, extinction, and humanity’s place in natural history. The public’s enduring fascination with dinosaurs demonstrates the power of scientific discovery to capture imagination and inspire wonder, even when challenging fundamental beliefs about the world.

Perhaps most importantly, the initial reaction to dinosaur discoveries revealed the public’s capacity for embracing scientific knowledge that fundamentally changed their understanding of reality. This willingness to accept revolutionary concepts, despite their disturbing implications, speaks to humanity’s remarkable ability to adapt its worldview in response to new evidence. The legacy of those first encounters with dinosaurs reminds us that scientific discovery is not just about understanding the past—it’s about reshaping our vision of the future.

Did you imagine that a few scattered bones could fundamentally reshape how an entire civilization understood its place in the universe?