Dinosaurs dominated Earth for over 165 million years, evolving into countless specialized forms with unique physical attributes. These prehistoric creatures developed bodies perfectly adapted to their ecological niches, with features that, when viewed through a whimsical modern lens, might have made them perfectly suited for various human occupations. Construction work, with its demands for strength, size, specialized abilities, and teamwork, presents a particularly interesting thought experiment. If dinosaurs had somehow coexisted with humans and joined our workforce, several species would have made exceptional construction workers based on their physical attributes and presumed behavioral characteristics. This playful exploration combines paleontological facts with imagination to consider which dinosaur species might have excelled in the construction industry.

The Brachiosaurus: Nature’s Living Crane

Standing at approximately 40-50 feet tall, the Brachiosaurus would have been the ultimate living crane on any construction site. Its immense height and long neck would have allowed it to lift and place materials at heights that would otherwise require expensive machinery. With an estimated weight of 35-80 tons and tremendous strength, this gentle giant could have easily lifted heavy steel beams, pre-fabricated wall sections, or roofing materials to upper levels of buildings under construction. Their relatively calm demeanor (as suggested by their herbivorous lifestyle) would have made them reliable operators, patiently moving materials throughout the day with minimal fuss. Imagine a construction site where instead of metal cranes dotting the skyline, a team of Brachiosaurus carefully positioned materials with their natural lifting capabilities.

Ankylosaurus: The Demolition Specialist

With its heavily armored body and powerful club-like tail, the Ankylosaurus would have been the perfect dinosaur for demolition work. This tank-like creature, weighing around 4-8 tons, possessed a tail club that could swing with tremendous force, easily breaking through concrete walls and other structures slated for removal. Their low center of gravity and wide stance would have provided exceptional stability during demolition operations, preventing accidental falls or tip-overs. The thick osteoderms covering their backs would have served as built-in protection from falling debris, eliminating the need for hard hats or protective gear. Construction companies would have valued these natural demolition experts for their ability to precisely target structural weak points while remaining protected from the hazards of the job.

Triceratops: The Bulldozing Powerhouse

The robust build and three prominent horns of the Triceratops would have made it nature’s perfect bulldozer. Weighing up to 12 tons and equipped with a powerful frame, these dinosaurs could have easily pushed massive amounts of earth, cleared construction sites, and leveled terrain for new building projects. Their broad, shield-like frill would have provided additional pushing surface when clearing larger obstacles or debris piles. Triceratops’ naturally strong neck muscles, evolved to support their massive heads, would have translated perfectly to pushing heavy loads across construction sites. Their forward-facing horns could have been fitted with specialized attachments for more precise earth-moving operations, making them versatile additions to any construction team requiring heavy-duty ground preparation.

Stegosaurus: The Plate-Backed Material Transporter

The distinctive back plates of the Stegosaurus would have made it an ideal platform for transporting construction materials across job sites. These large, flat surfaces could have been easily modified to securely hold stacks of lumber, pipes, or other building materials. Weighing around 5-7 tons but with a relatively gentle disposition, Stegosaurus could have carried substantial loads without damaging delicate materials. Their low-slung bodies would have made loading and unloading more accessible than with taller dinosaurs, while their spiked tails could have been useful for puncturing packaging materials or creating drainage holes. Construction site managers would have appreciated the Stegosaurus’ steady pace and reliable nature, making them dependable material transporters for daily operations.

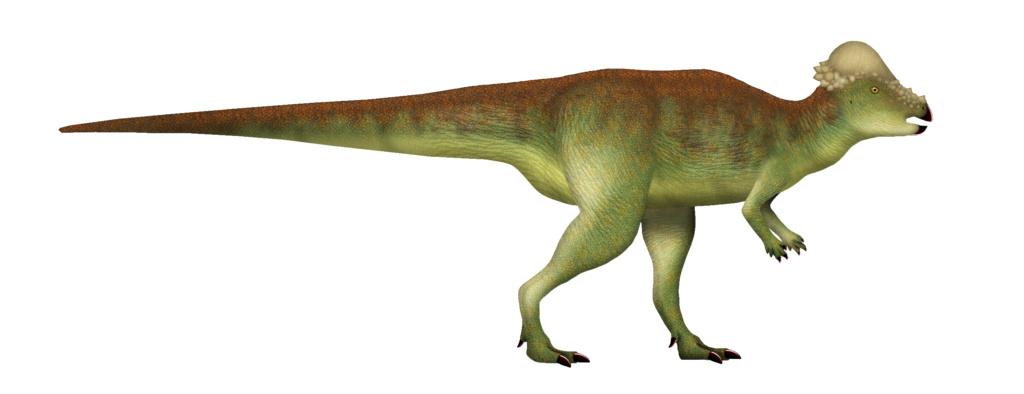

Pachycephalosaurus: The Hard-Headed Compactor

With its incredibly thick, dome-shaped skull reaching up to 10 inches of solid bone, the Pachycephalosaurus would have made an excellent natural compactor for construction projects. These medium-sized dinosaurs could have used their reinforced heads to tamp down soil, compact gravel beds, or firm up foundation areas with remarkable precision. Their naturally developed head-butting behavior would have translated perfectly to the rhythmic motion needed for effective soil compaction. At approximately 15 feet long, they would have been maneuverable enough to work in relatively tight spaces where larger equipment might not fit. Construction crews would have valued these living compactors for their ability to apply significant force exactly where needed, potentially eliminating the need for mechanical compacting equipment in many applications.

Parasaurolophus: The Communication Specialist

The Parasaurolophus, with its distinctive hollow crest that functioned as a resonating chamber, would have served as the construction site’s communication specialist. These hadrosaurs could produce loud, clear calls that would have carried across even the noisiest construction environments, alerting workers to shift changes, emergencies, or important announcements. Their estimated vocal range, which some paleontologists believe could have carried for miles, would eliminate the need for electronic PA systems or radios in many situations. Standing at a manageable 10 feet tall and 30 feet long, they would have been large enough to be visible across a job site but not so massive as to be unwieldy in more confined spaces. Their likely herd behavior suggests they would have been naturally cooperative team members, responsive to leadership and capable of coordinated efforts.

Therizinosaurus: The Multipurpose Tool Operator

The Therizinosaurus, with its extraordinary three-foot-long claws, would have been the construction industry’s ultimate multipurpose tool operator. These massive claws could have served numerous functions: digging precise trenches for foundation work, cutting through tough materials like root systems or soft stone, and even providing fine manipulation for detailed finishing work. Despite their fearsome appearance, paleontologists believe these dinosaurs were primarily herbivores, suggesting a gentler temperament suitable for careful work. Standing up to 16 feet tall and 33 feet long, they would have combined reach with precision in a way no other dinosaur could match. Their bipedal stance would have freed their impressive forelimbs for dedicated tool operation, making them versatile workers capable of adapting to various construction tasks throughout a project’s lifecycle.

Spinosaurus: The Waterworks Specialist

As the largest known carnivorous dinosaur and one adapted for a semi-aquatic lifestyle, the Spinosaurus would have excelled at construction projects involving water management. Their powerful swimming abilities and comfort in aquatic environments would have made them ideal for building dams, bridges, underwater foundations, and drainage systems. Standing up to 23 feet tall with a length of over 50 feet, these massive creatures could have worked in significant water depths without specialized equipment. Their long, crocodile-like snouts would have allowed for precise placement of underwater structural elements, while their powerful limbs could have anchored materials against strong currents. Construction firms specializing in ports, harbors, or riverside development would have particularly valued these natural waterworks specialists for their unique combination of size and aquatic adaptation.

Diplodocus: The Living Conveyor Belt

The extraordinarily long-necked Diplodocus, stretching up to 90 feet from head to tail, would have functioned as nature’s perfect conveyor belt on construction sites. Their remarkable length would have enabled them to transfer materials across significant distances without the need for mechanical conveyor systems or multiple handling points. With relatively small heads compared to their massive bodies, they could have precisely picked up and placed smaller components where needed along their extensive reach. Their whip-like tails could have been used to sweep areas clean or move lightweight materials across the ground. Construction managers would have positioned these living conveyor belts strategically to create efficient material flow pathways across large construction sites, dramatically improving logistical operations and reducing the need for fossil fuel-powered equipment.

Utahraptor: The Precision Cutter and Detailer

The Utahraptor, with its incredibly sharp claws and high intelligence (relative to other dinosaurs), would have excelled at precision cutting and detail work on construction sites. These 23-foot-long dromaeosaurs possessed sickle-shaped claws that could have sliced through materials with surgical precision, from trimming excess materials to creating detailed architectural features. Their presumed high dexterity and coordination, suggested by their hunting behaviors, would have allowed them to handle intricate tasks requiring a gentle touch despite their fearsome appearance. Their binocular vision would have given them excellent depth perception for judging distances and alignments in finishing work. Construction teams would have assigned these clever dinosaurs to high-value finishing tasks where their natural cutting tools and intelligence would minimize costly errors and maximize craftsmanship.

Maiasaura: The Construction Site Caretaker

Known from fossil evidence as attentive parents who cared for their young in nesting colonies, Maiasaura would have made excellent construction site caretakers and support personnel. These 30-foot-long hadrosaurs could have maintained site cleanliness, organized materials, and provided general support to more specialized dinosaur workers. Their documented nurturing behaviors suggest they would have been attentive to the needs of others, perhaps even providing basic first aid or care for injured workers. Their medium size would have allowed them to navigate most areas of a construction site while still being large enough to handle significant maintenance tasks. Construction companies would have valued these reliable, caring dinosaurs for creating an organized, well-maintained work environment that improved efficiency and safety for all other dinosaur workers.

Pteranodon: The Aerial Surveyor and Inspector

While technically not dinosaurs but flying reptiles, Pteranodons would have been invaluable additions to any construction team as aerial surveyors and inspectors. With wingspans reaching up to 23 feet, these pterosaurs could have quickly accessed and inspected hard-to-reach areas of tall structures without scaffolding or lifts. Their excellent vision would have allowed them to spot structural issues, safety hazards, or quality control problems from unique aerial perspectives. Their ability to land on narrow perches would have enabled close inspection of areas that might be dangerous for larger dinosaurs to approach. Construction managers would have deployed these flying specialists to conduct daily site surveys, monitor progress from above, and provide immediate feedback on areas requiring attention, dramatically improving site safety and quality assurance processes.

Managing a Dinosaur Construction Crew: Challenges and Benefits

Managing a diverse team of dinosaur construction workers would have presented unique challenges and remarkable benefits. Feeding requirements alone would have been staggering, with some of the larger sauropods requiring hundreds of pounds of vegetation daily to maintain their working strength. Safety protocols would have needed complete reimagining, with considerations for tail swing radii, territorial behaviors, and species-specific stress responses. Communication systems would have evolved to incorporate visual signals, sound patterns, and perhaps specialized dinosaur handlers trained to interpret and direct different species. The benefits, however, would have been equally impressive: dramatically reduced dependency on fossil fuels, natural lifting and earth-moving capabilities that exceed our most powerful machines, and work crews that could potentially self-heal from minor injuries. Construction timelines might have actually accelerated despite the seemingly primitive nature of dinosaur labor, as dozens of specialized dinosaurs could work simultaneously without the logistical delays of bringing in and setting up equivalent mechanical equipment.

In this whimsical thought experiment, we can see how the remarkable evolutionary adaptations of different dinosaur species might have translated into specialized construction roles in a human world. While dinosaurs and humans never coexisted, this playful exploration highlights the incredible specialization these ancient creatures developed over millions of years of evolution. Each species evolved physical characteristics perfectly suited to their environmental niches – characteristics that, in our imagination at least, might have made them the ultimate construction workers. Perhaps there’s something to learn from these ancient specialists as we continue to develop our own construction technologies, seeking efficiency, sustainability, and natural solutions to our building challenges.