Millions of years ago, a fearsome predator stalked the semi-arid landscape of what is now Madagascar. With its powerful jaws and robust build, Majungasaurus crenatissimus established itself as the apex predator of its island ecosystem. Perhaps most intriguingly, this Late Cretaceous theropod has earned a macabre nickname—”the cannibal dinosaur”—due to compelling evidence that it occasionally preyed upon members of its species. This prehistoric hunter offers paleontologists a fascinating window into dinosaur evolution on isolated landmasses and reveals surprising behaviors that challenge our understanding of these ancient reptiles.

Discovery and Naming

Majungasaurus was first discovered in northwestern Madagascar in the late 19th century, though initial finds consisted only of fragmentary remains. The genus name derives from Mahajanga (formerly spelled Majunga), the province where the fossils were unearthed, combined with the Greek “sauros,” meaning lizard. The species name “crenatissimus” refers to the distinctive serrated teeth that would later become one of its identifying features. For decades, this dinosaur remained poorly understood, with some experts initially misclassifying it as a pachycephalosaur (dome-headed dinosaur) based on limited skull material. It wasn’t until more complete specimens were discovered in the 1990s and 2000s that scientists gained a comprehensive understanding of this remarkable predator.

Geological Context

Majungasaurus inhabited Madagascar during the Late Cretaceous period, specifically from about 70 to 66 million years ago, just before the mass extinction event that wiped out non-avian dinosaurs. During this time, Madagascar had already separated from mainland Africa and the Indian subcontinent, creating an isolated environment where unique evolutionary adaptations could flourish. The dinosaur’s remains are primarily found in the Maevarano Formation, a geological layer consisting of sandstones and mudstones that represent ancient floodplains and river systems. Paleoclimatic studies suggest this region experienced pronounced wet and dry seasons, creating a challenging environment where adaptability would have been crucial for survival. This isolation likely contributed to the distinctive characteristics that set Majungasaurus apart from its mainland relatives.

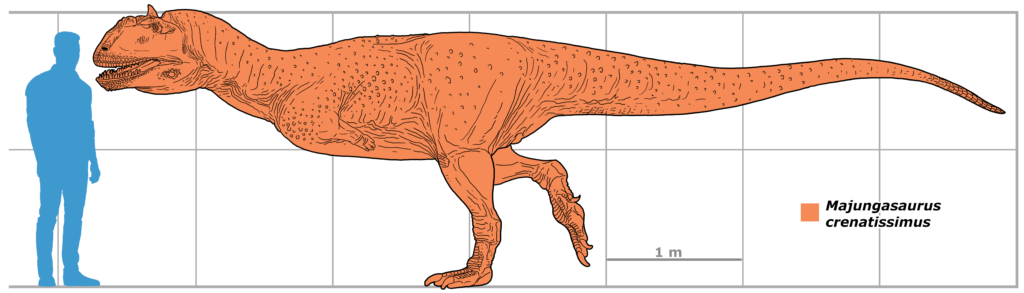

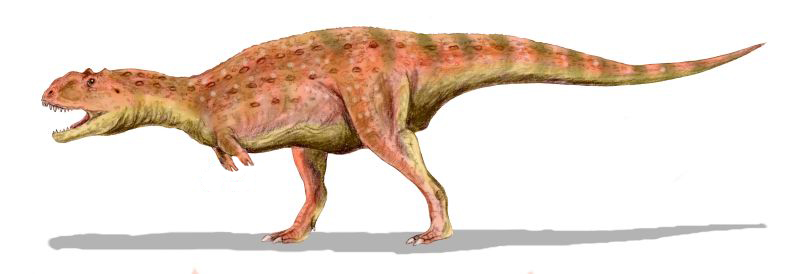

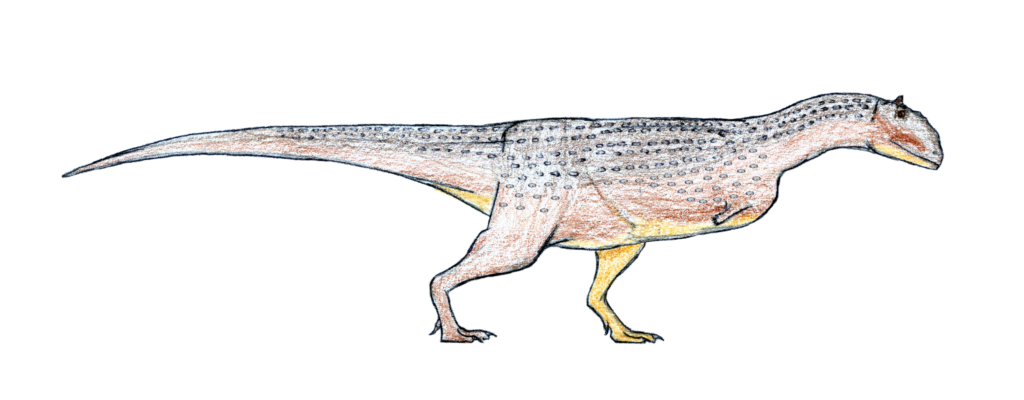

Physical Characteristics

Majungasaurus was a medium-sized theropod dinosaur measuring approximately 20-23 feet (6-7 meters) in length and weighing around 1.1-1.5 tons. Unlike the sleeker, more agile predators like Velociraptor, this dinosaur had a stockier, more robust build with relatively short but powerful hindlimbs and extraordinarily reduced forelimbs that were even smaller proportionally than those of Tyrannosaurus rex. Its skull was particularly distinctive, featuring a single rounded horn or dome-like protuberance on top, the function of which remains debated among paleontologists. Some suggest it may have been used in head-butting contests between rivals, while others propose it served as a display structure to attract mates or recognize members of the same species. The dinosaur’s jaws housed dozens of thick, blade-like teeth ideal for slicing through flesh and crushing bone.

Taxonomic Classification

Majungasaurus belongs to the family Abelisauridae, a group of predatory dinosaurs that dominated the Southern Hemisphere continents during the Late Cretaceous period. Abelisaurids are characterized by their short, deep skulls, reduced forelimbs, and often rugose (rough-textured) facial bones. Within this family, Majungasaurus is most closely related to other abelisaurids from India and South America, reflecting the ancient connections between these landmasses before continental drift separated them. This taxonomic placement helps paleontologists understand the biogeographical distribution of dinosaurs during the Cretaceous and provides evidence for how plate tectonics influenced dinosaur evolution. Majungasaurus represents one of the most completely known abelisaurids, making it crucial for understanding this important but still relatively mysterious dinosaur family.

Evidence of Cannibalism

The most headline-grabbing aspect of Majungasaurus biology emerged in 2007 when researchers published evidence of cannibalistic behavior in this dinosaur. Scientists examining fossil bones found distinctive tooth marks that precisely matched the size, shape, and spacing of Majungasaurus teeth. What made this discovery remarkable was that these tooth marks were found on the bones of other Majungasaurus individuals. The marks showed patterns consistent with active predation rather than simple scavenging, suggesting that these dinosaurs deliberately hunted and consumed members of their species. While cannibalism is known in some modern predators, particularly during times of resource scarcity, this provided the first concrete evidence of such behavior in large theropod dinosaurs. This discovery fundamentally changed how paleontologists view predatory behavior in extinct reptiles and hinted at the harsh survival pressures present in late Cretaceous Madagascar.

Hunting Strategy and Diet

Majungasaurus was the undisputed apex predator of its ecosystem, with a hunting strategy likely dictated by its physical attributes. Unlike the swift-running tyrannosaurs or dromaeosaurs, its relatively short legs suggest it was not built for pursuing prey over long distances. Instead, paleontologists believe it was an ambush predator, using stealth and short bursts of speed to capture prey. Tooth mark analysis indicates that Majungasaurus fed on sauropods (particularly Rapetosaurus, a titanosaur that shared its habitat) and other herbivorous dinosaurs. Its robust jaw and teeth were well-adapted for delivering powerful bites and tearing flesh from its victims. Additionally, the unusual depth of some tooth marks suggests it may have practiced “puncture-and-pull” feeding, where the predator would sink its teeth deep into prey and then pull backward to remove chunks of meat—a feeding style seen in some modern reptiles.

Ecosystem and Contemporaries

Late Cretaceous Madagascar hosted a diverse but relatively limited fauna, creating a unique island ecosystem where Majungasaurus reigned supreme. Among its contemporaries were the aforementioned Rapetosaurus, a long-necked titanosaur sauropod that likely served as its primary prey, and Masiakasaurus, a smaller, peculiar theropod with forward-projecting front teeth. The ecosystem also included prehistoric crocodiles, birds, mammals, and various amphibians that have been preserved in the same formations. The relatively small number of large vertebrate species suggests that island isolation had already begun to affect Madagascar’s biodiversity. This isolated environment may help explain some of Majungasaurus’s unique adaptations and behaviors, including cannibalism, which might have evolved as a response to periodic resource limitations on an island with fewer prey species than mainland ecosystems.

Brain and Sensory Capabilities

Studies of Majungasaurus brain endocasts (internal casts of the braincase) have provided intriguing insights into this dinosaur’s cognitive abilities and sensory adaptations. While its brain was relatively small compared to its body size—typical for large reptiles—it showed enlargement in areas associated with smell, suggesting a well-developed sense of olfaction that would have aided in locating prey or carrion. The orientation of its semicircular canals, structures related to balance and spatial orientation, indicates that Majungasaurus had good coordination and body awareness despite its bulky build. Interestingly, the brain regions associated with vision appear less developed than in some other theropods, suggesting Majungasaurus may have relied more heavily on smell than sight when hunting. These neuroanatomical features help paleontologists reconstruct not just how this dinosaur looked but how it experienced and interacted with its ancient world.

Growth and Development

Analysis of Majungasaurus bone microstructure has revealed fascinating details about how these animals grew and developed throughout their lives. By studying growth rings in fossilized bones (similar to tree rings), scientists have determined that Majungasaurus grew relatively quickly during its early years but experienced a significant slowdown as it approached adult size. This growth pattern differs from that of large tyrannosaurs, which maintained rapid growth rates for longer periods. Specimens representing different life stages show that juvenile Majungasaurus had proportionally longer legs and potentially different feeding adaptations than adults, suggesting their ecological role may have shifted as they matured. The most complete growth series indicates these dinosaurs reached sexual maturity before attaining their full adult size, potentially at around 15-20 years of age. Such studies help paleontologists understand the life history of these extinct predators and draw comparisons with modern animals.

Unique Skeletal Features

Majungasaurus possessed several anatomical peculiarities that set it apart from other theropods and even from its closest abelisaurid relatives. Its cervical vertebrae (neck bones) had an unusual complex of interconnected air spaces that likely reduced weight while maintaining strength, a specialization that may have supported its relatively large head. The extremely reduced forelimbs of Majungasaurus represent an extreme case of limb reduction even among abelisaurids, with the arm bones showing signs of vestigiality—they had essentially become functionless through evolutionary reduction. Another distinctive feature was its rugose skull texture, with numerous small pits and protuberances giving the face a rough, almost “warty” appearance that may have supported keratinous structures in the living animal. These specialized features highlight how isolation on Madagascar likely drove unique evolutionary adaptations not seen in mainland dinosaurs.

Comparison to Other Predatory Dinosaurs

When compared to other large theropods like Tyrannosaurus or Allosaurus, Majungasaurus reveals fascinating evolutionary convergences and differences. While all these predators evolved powerful bites and carnivorous adaptations, they did so along different evolutionary pathways. Majungasaurus had a shorter, deeper skull than tyrannosaurs, with teeth designed more for tearing than crushing. Unlike the relativity gracile allosaurids with their longer arms and slashing feeding style, Majungasaurus evolved extremely reduced forelimbs and a more powerful bite-oriented killing strategy. Its closest relatives were other Southern Hemisphere abelisaurids like Carnotaurus from South America and Rajasaurus from India, though Majungasaurus appears to have been more robustly built than these cousins. These comparisons help paleontologists understand how different predatory niches evolved on different continents and how isolation influenced the development of unique adaptations in separated dinosaur populations.

Extinction Context

Majungasaurus existed until very near the end of the Cretaceous period, disappearing in the mass extinction event that claimed all non-avian dinosaurs approximately 66 million years ago. The timing of Majungasaurus’s extinction coincides with the Chicxulub asteroid impact and associated global catastrophes, including atmospheric changes, temperature fluctuations, and widespread habitat destruction. As an apex predator dependent on large herbivores for sustenance, Majungasaurus would have been particularly vulnerable to ecosystem collapse. Interestingly, the isolation of Madagascar might have initially protected its fauna from some extinction pressures facing mainland species, but ultimately could not shield them from the global nature of the K-Pg extinction event. The disappearance of Majungasaurus cleared the way for mammals to eventually become the dominant large vertebrates on Madagascar, ultimately leading to the evolution of the island’s famous lemurs and other unique mammalian fauna.

Cultural Significance and Popular Representation

Since its cannibalistic behavior was discovered, Majungasaurus has captured the public imagination and become one of the more recognizable dinosaurs from the Southern Hemisphere. It has been featured in several dinosaur documentaries, including episodes of the BBC’s “Planet Dinosaur” series, where its distinctive head horn and predatory behavior were highlighted. Museum exhibits around the world showcase Majungasaurus reconstructions, often emphasizing its status as Madagascar’s top predator. The dinosaur has also appeared in various paleontology books and children’s literature about dinosaurs, usually with emphasis on its unusual cannibalistic behavior. Despite not having the household name recognition of Tyrannosaurus or Velociraptor, Majungasaurus has carved out a niche in popular culture as “the cannibal dinosaur,” demonstrating how distinctive behaviors can make certain prehistoric animals particularly fascinating to the public. Its unique island evolution story also helps illustrate broader concepts about biogeography and adaptation to science enthusiasts.

Ongoing Research and Recent Discoveries

Paleontological work on Majungasaurus continues to yield new insights about this fascinating predator. Recent expeditions to the Maevarano Formation have uncovered additional specimen material, including better-preserved forelimbs that provide further evidence of their extreme reduction. Advanced imaging techniques are revealing previously undetectable details about its skull anatomy and potential soft-tissue structures. Isotopic analysis of Majungasaurus teeth is shedding light on its diet and the seasonal variations in food availability it may have faced. Current research is also exploring the biomechanics of its unusual skull, with computer modeling suggesting it had a surprisingly powerful bite force for its size. As technology advances, even existing museum specimens are yielding new information through CT scanning and other non-destructive analytical techniques. These ongoing studies continue to refine our understanding of this unique predator and its place in dinosaur evolution, demonstrating how paleontology remains a dynamic field where discoveries constantly enhance our picture of prehistoric life.

Conclusion

Majungasaurus stands as a remarkable testament to the power of isolated evolution and the diversity of dinosaur adaptations. From its distinctive horned skull to its extremely reduced forelimbs, and perhaps most notably its documented cannibalistic behavior, this predator carved out a unique evolutionary path on its island home. The story of Madagascar’s “cannibal dinosaur” reminds us that prehistoric ecosystems were complex webs of interaction, where survival often demanded specialized adaptations and sometimes extreme behaviors. As paleontologists continue to unearth and analyze fossils from this fascinating theropod, Majungasaurus will undoubtedly continue to enhance our understanding of dinosaur biology, predator-prey relationships, and the evolutionary consequences of geographical isolation.