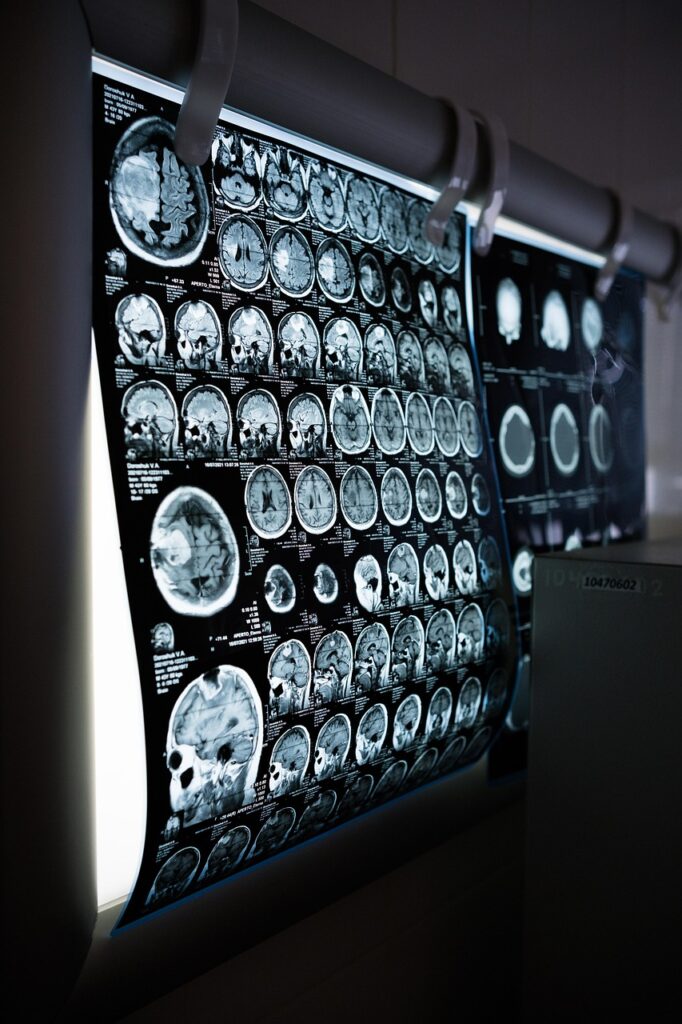

Functional MRI scans have exposed how individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder engage additional neural networks to handle cognitively demanding sequences, despite matching healthy peers in accuracy.

Performance Matches, But Brains Diverge

Performance Matches, But Brains Diverge (Image Credits: Pixabay)

Participants with OCD navigated a complex task with the same precision as controls, yet their brain activity painted a picture of heightened effort.

Lead researcher Hannah Doyle, a postdoctoral associate in Theresa Desrochers’ lab at Brown University’s Carney Institute for Brain Science, explained the motivation behind the work. OCD symptoms frequently involve losing track or becoming stuck in routines, such as the abstract sequences encountered in daily activities like dressing or organizing tasks. This study targeted those disruptions head-on.

Theresa Desrochers, an associate professor of brain science and psychiatry, highlighted a key gap in prior research. Clinical assessments often rely on static exercises. Real-world demands, however, require juggling multiple cognitive systems in dynamic order.

Decoding the Sequential Task

Inside an MRI scanner, subjects identified colors or shapes of objects following strict patterns, like “color, color, shape, shape.” This setup demanded ongoing tracking and categorization amid shifting stimuli.

The design mimicked everyday decision-making more closely than traditional tests. Researchers captured real-time brain responses to reveal how sequencing taxes cognitive control, working memory, and perception. No behavioral gaps emerged between groups, underscoring the subtlety of neural differences.

Newly Spotlighted Brain Zones

OCD patients activated regions beyond those seen in controls, particularly for motor control, memory, and recognition. Heightened signals appeared in:

- The middle temporal gyrus, aiding working memory, semantic retrieval, and language.

- An area bridging the occipital gyrus and temporo-occipital junction, handling visual processing and object identification.

These zones had not previously linked to OCD, according to Doyle. “Their behaviour looked similar, but the brains of the participants with OCD recruited more brain regions than the people in the control group,” she stated.

The findings appeared in Imaging Neuroscience on January 6, 2026. Access the full study here.

Treatment Horizons Expand

Co-author Nicole McLaughlin, a neuropsychologist at Butler Hospital and Brown associate professor, sees direct applications for transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). The FDA approved TMS for OCD in 2018, yet it benefits only 30% to 40% of patients.

Targeting coils nearer these novel regions could boost outcomes. “If we reposition coils during TMS treatments to be near these brain regions, we might end up seeing a greater improvement in symptoms,” McLaughlin suggested. The task itself holds promise as a progress marker. Post-treatment scans showing normalized activity might signal success.

These insights shift OCD research toward dynamic, real-life cognition. By pinpointing compensatory neural strategies, scientists edge closer to precision therapies that address root inefficiencies.

- OCD brains recruit extra areas like the middle temporal gyrus during sequences, despite equal task performance.

- Findings suggest refined TMS targeting for better symptom relief.

- The sequential task could track treatment response through brain changes.

Precision interventions may soon redefine OCD management. What are your thoughts on these neural discoveries? Share in the comments.