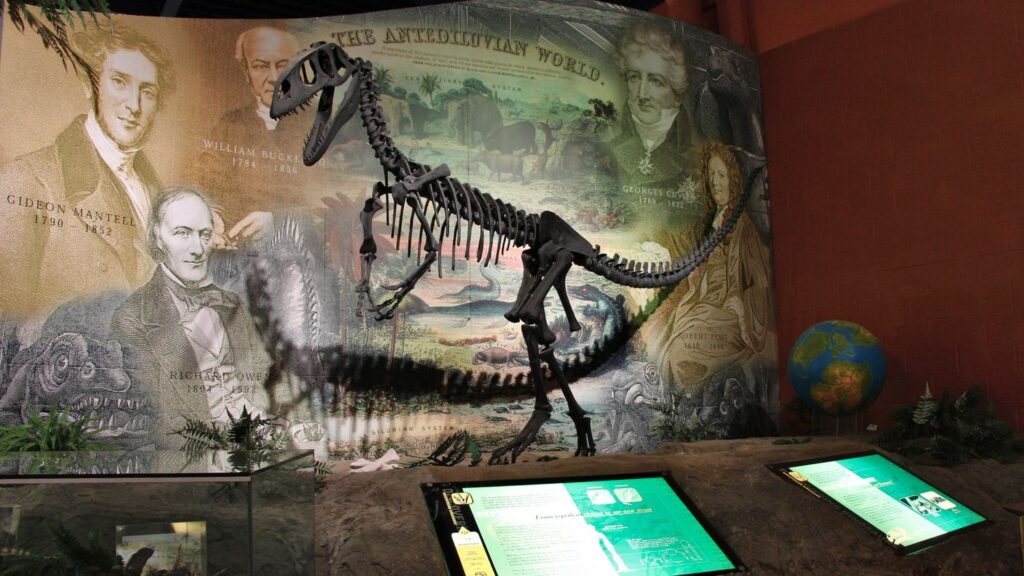

Imagine standing in a museum, staring up at a towering skeleton of a Tyrannosaurus rex, and suddenly realizing that scientists still do not fully understand how it lived, what it felt, or even how it died. That is the peculiar thrill of paleontology. It is a science built on fragments, on broken bones, on clues locked inside stone for millions of years, waiting to be decoded.

What you are about to read is not a tidy list of answered questions. Far from it. These are the puzzles that keep the world’s best fossil hunters awake at night, the riddles that newer technology has barely scratched. Some have recently gotten closer to being solved. Others seem to deepen every time a new discovery is made. So let’s dive in.

The Nanotyrannus Debate: One Dinosaur or Two?

Back in 1942, researchers from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History found the skull of a small theropod in Montana’s Hell Creek Formation. After scientists classified it as the new species Nanotyrannus lancensis in 1988, that skull sparked four decades of fierce debate: do the fossils of small and slender tyrannosaurs represent a teenage version of the fearsome T. rex, or an entirely distinct dinosaur? Honestly, the fact that this argument raged on for so long tells you everything about how tricky it is to read prehistoric biology from ancient bones.

Using high-resolution scans, researchers found the Nanotyrannus skull contained more tooth sockets than a T. rex of any age, along with different routes for cranial nerves and sinuses. These features would have been established early in embryonic development and remain fixed for life. A computer-based evolutionary analysis positioned Nanotyrannus in a new clade just outside the T. rex line. Nanotyrannus and Tyrannosaurus could have lived alongside one another at the twilight of the dinosaur era, occupying different ecological niches. “Nanotyrannus was a completely different kind of predator: small, slender, extremely fast, with large predatory arms,” while T. rex was bulky, heavily built, with a huge head and powerful bite force. Still, not everyone is convinced. The debate, though leaning toward a resolution, may yet have more chapters to write.

The Cambrian Explosion: Where Did Everything Come From?

Here is something that should genuinely blow your mind. The Cambrian explosion involved the unparalleled emergence of organisms between 541 million and approximately 530 million years ago at the beginning of the Cambrian Period. The event was characterized by the appearance of many of the major phyla, between 20 and 35, that make up modern animal life. Think about that for a second. Virtually all the major body plans of animals alive today appeared in what is, geologically speaking, a blink of an eye. It is like nature suddenly flipped a switch.

Before early Cambrian diversification, most organisms were relatively simple, composed of individual cells or small multicellular organisms, occasionally organized into colonies. As the rate of diversification subsequently accelerated, the variety of life became much more complex and began to resemble that of today. Almost all present-day animal phyla appeared during this period, including the earliest chordates. Many scholars in paleontology, biology, geology, paleoclimatology and other disciplines have proposed various theories to try to reveal the mystery of the Cambrian explosion, but this problem has not been satisfactorily resolved, and it has been classified as one of the scientific problems by the international academic community. No single theory has won the day, and that fact alone makes the Cambrian explosion one of the most gripping open questions in all of science.

The Ediacaran Enigma: Life Before Life as We Know It

Rocks dating from 580 to 543 million years ago contain fossils of the Ediacaran biota, organisms so large that they are likely multicelled, but very unlike any modern organism. These strange creatures existed before the Cambrian explosion, and trying to classify them is a bit like trying to identify furniture from a civilization that no longer exists. You recognize the shapes but cannot figure out what they were used for.

At different times, Ediacaran creatures have been described as algae, fungi, lichens, unusual animals, or a completely new kingdom. Today, most paleontologists agree they were some sort of extinct animals, but the agreement ends there. There are still active debates about nearly everything, including “debates surrounding the timing and duration of key Ediacaran evolutionary events, and the age of the Ediacaran–Cambrian boundary itself.” Even with extraordinary fossil exposures spanning more than a thousand kilometers in places like Namibia and South Africa, the mystery surrounding these organisms refuses to yield a clean answer. That is both humbling and fascinating.

Were Dinosaurs Warm-Blooded or Cold-Blooded?

You might think this is an old question that has already been answered. It has not. Not fully. For decades, paleontologists have debated whether dinosaurs were warm-blooded, like modern mammals and birds, or cold-blooded, like modern reptiles. Knowing whether dinosaurs were warm- or cold-blooded could give hints about how active they were and what their everyday lives were like, but the methods to determine their warm- or cold-bloodedness were inconclusive.

Dinosaur metabolisms were diverse. Some lineages were cold-blooded like their lizard cousins, while others were warm-blooded like their avian relatives alive today. Paleontologists have suggested an array of arrangements, from a physiology that maintained a high, constant body temperature to big herbivorous dinosaurs warmed by fermenting vegetation in their guts. The latest hypothesis is that dinosaurs were mesotherms, relying on the activity of their muscles to warm their bodies but having body temperatures that could fluctuate. Dinosaur experts will undoubtedly continue to investigate and debate the point, especially given that dinosaurs took forms ranging from pigeon-size, feathery raptors to 110-foot, long-necked titans. I think the idea that metabolic strategies varied across different dinosaur groups is honestly the most satisfying answer we have, even if it sidesteps the clean resolution most people want.

What Was the Very First Dinosaur?

For paleontologists, the earliest species of any major lineage is always a sought-after critter. The trouble is that the fossil record is made up of snippets of life’s history, not the entire reel, so actually finding frames from the dawn of dinosaurs relies on luck as much as science. It is a bit like trying to reconstruct an entire film from three frames pulled at random. You can guess at the plot, but you cannot be sure.

Tracks found in Poland and skeletons from Tanzania belong to animals that were close, but not quite dinosaurs. Scientists have strong candidates, but the very first true dinosaur remains elusive. The fossil record simply does not preserve every creature that ever lived. Since most animal species are soft-bodied, they decay before they can become fossilized. As a result, although 30-plus phyla of living animals are known, two-thirds have never been found as fossils. When you frame it that way, it is remarkable we know as much as we do at all.

How Did Dinosaurs Really Die? The Full Story of the Mass Extinction

Everyone knows the asteroid story. A massive space rock slammed into the Yucatan Peninsula about 66 million years ago, and the non-avian dinosaurs were gone. The end. Except it is not nearly that simple. Yes, a massive asteroid struck the planet at that time, following a protracted period of global ecological change and intense volcanic activity at a spot called the Deccan Traps. But paleontologists haven’t fully pieced together how all these triggers translated into a mass extinction that killed off all the non-avian dinosaurs. Not to mention that most of what we know about the catastrophe comes from North America, even though dinosaurs lived around the globe.

There has been a long debate over whether the dinosaurs were slowly going extinct prior to the asteroid, or whether this main event singularly did them in. New finds in New Mexico reveal a species-rich and diverse dinosaur ecosystem thriving literally just before the impact. Coupled with other sites in North America, this research reveals that the dinosaurs might have kept going if space had not intervened. Paleontologists know the victims and the murder weapons, but they have yet to fully reconstruct how the ecological crime played out. That metaphor is perfect, honestly. It is a crime scene still under active investigation.

How Did Flight Evolve? The Origins of Birds

You look at a sparrow on a fence. You look at a T. rex skeleton. It almost seems insulting to suggest they are related. Yet birds are, by scientific consensus, living dinosaurs. The question of how flight actually evolved, however, is still wide open. New research in 2026 has even contested conclusions about the evolution of the ability of birds to move parts of the skull independently, arguing that prior findings were based on inadequate taxon sampling and morphological misinterpretations, while the original authors reaffirm their conclusion that powered prokinesis is most likely an autapomorphy of neognath birds. Even the fine mechanics of the bird skull remain a battlefield.

Much like the pterosaurs, bats appear suddenly in the fossil record already fully flight-adapted. Despite being the second-largest group of mammals, bats’ small fragile bones and terrestrial habitats make fossils of them incredibly rare, and transitional forms are still entirely unknown. The broader principle here applies to birds too. Transitional fossils are precious and rare. Archaeopteryx is famous and important, but a single species cannot tell the whole story of how powered flight emerged from a lineage of ground-dwelling or tree-climbing theropods. It is hard to say for sure, but the answer may lie in fossils not yet found.

The Biggest Dinosaur: A Title Nobody Can Officially Claim

Who is the biggest? It sounds like the simplest possible question. It is anything but. Of all the superlatives, the title of “biggest dinosaur” is among the most prized. But picking out a clear winner is confounded by quirks of evolution and the fossil record. Instead of just getting bigger on a straight trajectory through the entire Age of Dinosaurs, titanic sauropods evolved multiple times.

Length estimates for the largest dinosaurs, such as Supersaurus, Diplodocus, Argentinosaurus, Futalognkosaurus, and more, all come out around 100 to 110 feet or so, with variations in weight depending on the reconstructions. There is so much leeway in those numbers because the biggest dinosaurs are only known from partial skeletons, typically less than half the skeleton down to maybe one part of a single bone. That means paleontologists have to rely on smaller, more complete cousins of the giants to come up with size estimates, and these figures are often revised as researchers unearth new fossils. Scientists are preparing to publish new tyrannosaur growth studies that may refine predator diversity even further, while major digs in South America and Southeast Asia continue to hint at oversized species still waiting for names. There may be a bigger dinosaur than any we currently know, still buried somewhere in a hillside, waiting to be found. Now that is a thought.

Conclusion

Paleontology is, at its core, a science of incompleteness. You are working with fragments, clues, shadows of creatures that lived in worlds so different from ours they might as well be from another planet. Yet those fragments tell us astonishing things. Every new fossil reshapes what we thought we knew, and every mystery solved tends to crack open two or three more.

From the identity crisis of Nanotyrannus to the explosive puzzle of the Cambrian, from the warm blood debates to the elusive first dinosaur, these questions are not just academic. They connect to something deeply human: the need to know where life came from, how it works, and what it means that it can vanish in a geological instant.

The best part? You do not need a PhD to feel the pull of these mysteries. All you need is curiosity. So the next time you stare at a fossil under glass, remember that the scientists who put it there are still arguing about what it means. Which of these mysteries surprised you the most? Share your thoughts in the comments below.