The discovery of a Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton named “Stan” made headlines in 2020 when it sold for a record-breaking $31.8 million at auction, igniting intense debate within the scientific community and beyond. This astronomical price tag highlighted a growing tension between private fossil collectors and public institutions like museums. The question of whether ancient remains should be preserved for public education and scientific research or allowed to flow into private collections has become increasingly contentious. As dinosaur bones and other prehistoric artifacts fetch ever-higher prices on the open market, we must carefully consider where these irreplaceable windows into our planet’s past truly belong. This article explores the multifaceted debate around fossil ownership, examining the scientific, ethical, educational, and economic dimensions of this complex issue.

The Scientific Value of Fossils

Fossils represent irreplaceable data points in our understanding of evolution, extinction events, and ancient ecosystems. When properly excavated with scientific methodology, these remains provide contextual information about the environment, associated species, and geological time periods that extend far beyond the specimen itself. Professional paleontologists document precise locations, surrounding rock layers, and associated materials that help establish accurate dating and environmental reconstruction. This meticulous approach contrasts sharply with commercial collecting, where the priority often lies in extracting marketable specimens quickly rather than preserving scientific context. When fossils disappear into private collections, scientists lose access to potentially groundbreaking specimens that might answer fundamental questions about Earth’s biological history. The scientific community generally maintains that significant specimens should remain accessible for ongoing study as new technologies and methodologies continually reveal previously undetectable information from these ancient remains.

The Museum Perspective

Museums argue they serve as the ideal stewards for fossil specimens, ensuring both preservation and public access. These institutions employ trained conservators who maintain specimens in controlled environments designed to prevent deterioration over centuries. Unlike private collections, museums make their holdings available to qualified researchers from around the world, facilitating collaborative science that advances collective knowledge. Museums also fulfill a crucial educational mission by contextualizing specimens within comprehensive exhibits that explain their significance to millions of visitors annually. The American Museum of Natural History in New York, for instance, welcomes approximately 5 million visitors each year who can observe fossils alongside educational materials that explain evolutionary history and extinction events. Museum advocates point out that public institutions ensure intergenerational equity by preserving these natural heritage items for future scientists and citizens who deserve access to their shared planetary history.

Commercial Collecting and Market Forces

Commercial fossil hunting has evolved into a sophisticated industry operating worldwide, with annual auctions regularly achieving seven and eight-figure sales for premier specimens. Collectors range from wealthy individuals seeking conversation pieces to investment firms treating fossils as alternative assets in diversified portfolios. The high prices commanded by exceptional specimens have intensified collection efforts, particularly in regions with less stringent regulations regarding excavation and export. Countries like Mongolia and China have instituted strict laws prohibiting fossil exports, while the United States allows private collection from private lands but restricts it on federal property. Commercial collectors often argue they provide necessary funding for expensive excavations that might otherwise never occur, bringing specimens to light that would remain buried. They also contend that private interest in fossils has advanced preparation techniques and technologies that benefit the entire field, with innovations flowing between commercial and academic sectors.

Ethical Considerations of Ownership

The ethical dimension of fossil ownership extends beyond scientific access to questions of cultural and natural heritage. Many indigenous communities consider fossils found within their ancestral territories as integral components of their cultural patrimony, connecting them to the land and its history. When fossils are removed without consultation or consent, it can represent a continuation of colonial extraction practices that have historically disenfranchised native populations. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recognizes certain paleontological sites as World Heritage locations, acknowledging their universal value to humanity regardless of modern political boundaries. This raises fundamental questions about whether anyone can truly “own” the remnants of creatures that lived millions of years before human civilization. Ethical frameworks increasingly emphasize stewardship over ownership, suggesting that whoever possesses fossils should prioritize their preservation and accessibility rather than treating them as private property with no obligations to the broader community.

Legislative Frameworks Worldwide

Countries have developed strikingly different approaches to regulating fossil collection and ownership, reflecting varying perspectives on natural heritage management. Brazil and Argentina have established some of the strictest regulations, declaring fossils state property regardless of where they’re found, making private collection essentially illegal. The United States operates under a complex patchwork where fossils found on private land belong to the landowner, while those on federal lands are public property requiring permits for scientific collection. China, following numerous high-profile smuggling cases, has implemented comprehensive laws designating fossils as cultural relics with severe penalties for illegal exportation. Australia requires export permits for significant specimens, attempting to balance private rights with national interest in retaining scientifically important material. These divergent approaches create considerable complications in international paleontology, as specimens legally collected in one jurisdiction may be considered illicitly obtained when crossing borders, creating challenges for both commercial dealers and research institutions seeking to build representative collections.

Funding Challenges in Paleontology

Museum acquisition budgets have failed to keep pace with the escalating market values of exceptional fossils, creating a widening gap between institutional capabilities and private purchasing power. Major natural history museums typically allocate between $20,000 and $200,000 annually for fossil acquisitions, figures that appear modest compared to multi-million-dollar auction prices for premier specimens. This funding disparity has forced museums to rely increasingly on donations, corporate sponsorships, and philanthropic partnerships to secure significant specimens. Field expeditions themselves require substantial resources, with major dinosaur excavations often costing hundreds of thousands of dollars for transportation, equipment, staff, and proper documentation. Commercial collectors argue that their operations provide necessary capital for discovering specimens that would otherwise remain buried indefinitely, while critics counter that profit motives can lead to rushed, scientifically compromised excavations. Some innovative museums have developed hybrid models, partnering with commercial collectors to share costs while ensuring proper scientific protocols and public access.

The Case for Private Ownership

Advocates for private fossil collecting emphasize that market incentives drive discovery and innovation in ways institutional science sometimes cannot match. Private collectors have funded expeditions to remote regions that academic institutions overlooked, resulting in discoveries of new species and expansion of the fossil record. Many significant museum specimens were initially discovered by commercial collectors who recognized their importance and facilitated their transition to public institutions. Private ownership also distributes preservation responsibilities across a broader network rather than concentrating all specimens in potentially vulnerable institutional collections. The Black Hills Institute in South Dakota represents a hybrid model, operating as a commercial entity that nevertheless maintains a publicly accessible museum and collaborates extensively with academic researchers. Supporters also point out that private enthusiasm for fossils creates constituencies advocating for paleontological science and conservation, with many amateur collectors providing valuable field assistance to professional paleontologists and donating significant finds to museums.

Educational Impact and Public Engagement

Museums excel at contextualizing fossils within broader educational frameworks that explain evolutionary processes, extinction events, and ancient ecosystems to diverse audiences. These institutions design exhibits specifically to translate complex scientific concepts into accessible learning experiences, serving millions of schoolchildren annually through formal educational programs. Private collections, even when displayed in personal museums, typically lack the interpretive infrastructure and educational expertise to maximize public learning opportunities. However, some private collectors have developed innovative approaches to sharing their specimens, including traveling exhibitions that reach communities without major natural history museums. Digital technologies are increasingly blurring these distinctions, with high-resolution scanning and virtual reality models potentially allowing remote access to specimens regardless of physical location. The educational power of encountering authentic fossils remains profound, with studies showing significantly higher engagement and retention when learners interact with genuine specimens rather than replicas or digital representations.

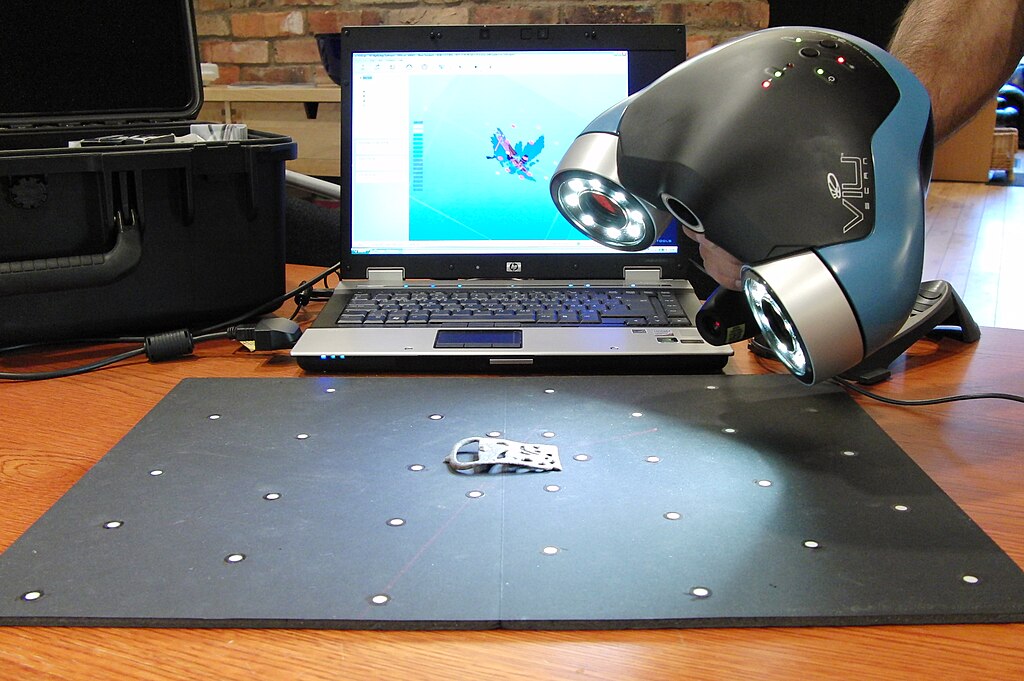

The Replication Solution

Advanced casting and 3D printing technologies offer potential middle ground in the ownership debate by creating scientifically accurate replicas virtually indistinguishable from original specimens. Modern molding compounds capture microscopic surface details, allowing researchers to study morphological features from replicas while original specimens remain secure in controlled environments. The Smithsonian Institution and other major museums have established sophisticated replication programs that produce museum-quality casts for research, education, and exhibition worldwide. These technologies democratize access to rare specimens, allowing regional museums and educational institutions to display accurate representations of fossils they could never afford to acquire. For research purposes, digital scanning at microscopic resolution enables scientists to collaborate remotely on specimen analysis without requiring physical access to fragile originals. While purists argue that replicas lack the authenticity and complete data signature of originals, the replication approach significantly expands access while reducing pressure on museums to compete financially for original specimens.

Notable Controversies and Legal Battles

The fossil trade has generated numerous high-profile legal disputes that illuminate the complex tensions between commercial, scientific, and cultural interests. The famous Tyrannosaurus rex specimen “Sue,” discovered in South Dakota in 1990, became the center of a protracted legal battle involving the FBI, tribal authorities, landowners, and commercial paleontologists before eventually selling for $8.36 million to the Field Museum in Chicago. More recently, the nearly complete Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton repatriated to Mongolia in 2013 after being illegally exported and offered at a New York auction highlighted issues of national patrimony laws and international fossil trafficking. The Morrison Formation in the American West has become particularly contentious as commercial collectors compete with research teams for access to productive dinosaur localities on both public and private lands. These cases reveal the inadequacy of existing legal frameworks to address the complex intersection of science, commerce, and heritage preservation represented by paleontological specimens, often resulting in ad hoc resolutions rather than systematic policy solutions.

Digital Access and Virtual Paleontology

Emerging digital technologies are transforming how scientists and the public interact with fossil specimens, potentially reconfiguring the ownership debate. Advanced CT scanning, photogrammetry, and laser scanning now produce digital models so detailed they reveal features invisible to direct observation, including internal structures and microscopic surface characteristics. Major initiatives like MorphoSource at Duke University and Digitalfossil.org are building open-access repositories of digital fossil data that researchers worldwide can access regardless of where physical specimens reside. These technologies enable non-destructive analysis of fragile specimens and facilitate unprecedented collaboration across institutions and national boundaries. For educational purposes, augmented and virtual reality applications allow students to manipulate virtual fossils and visualize extinct creatures in their ancient environments, potentially delivering more engaging learning experiences than static museum displays. While digital access cannot entirely replace the scientific value of physical specimens, it significantly reduces barriers to information sharing and may eventually render the physical location of original specimens less critical to advancing paleontological knowledge.

Compromise Models and Future Directions

Recognizing the legitimate interests of various stakeholders, innovative compromise models are emerging that balance scientific, commercial, and educational priorities. Some jurisdictions have implemented “report and release” protocols where commercial collectors must document significant finds and offer first right of refusal to public institutions before selling to private collectors. Public-private partnerships between museums and commercial collectors have successfully funded major expeditions with agreements ensuring scientific access while allowing commercial interests to market less significant specimens or replicas. The Jurassic Foundation represents another collaborative approach, channeling funds from commercial fossil enterprises and entertainment franchises into grants for paleontological research and education. Looking forward, blockchain technology offers potential for tracking provenance and maintaining scientific information even as specimens change hands, potentially creating systems where ownership rights and scientific access can be separately managed. These evolving frameworks suggest possibilities for cooperative rather than competitive relationships between commercial and institutional paleontology that maximize both discovery and scientific knowledge advancement.

Conclusion: Balancing Competing Values

The debate over fossil ownership ultimately reflects a tension between different but legitimate values: scientific advancement, educational access, cultural heritage, property rights, and market principles. No single solution can perfectly satisfy all these concerns, suggesting the need for nuanced approaches tailored to specific contexts and specimen types. Particularly rare or scientifically significant specimens arguably deserve special consideration, with stronger presumptions favoring public access and permanent scientific availability. For more common fossils, private collection may actually advance discovery while allowing museums to focus limited resources on truly exceptional specimens. Moving forward, the most productive path likely involves developing more sophisticated frameworks that acknowledge both the scientific imperative for information preservation and the practical realities of discovery financing. By emphasizing collaboration over confrontation, the paleontological community can work toward systems that maximize what matters most: expanding human knowledge about our planet’s extraordinary history while ensuring these irreplaceable treasures remain available for generations to come.