Styracosaurus, meaning “spiked lizard,” stands as one of the most visually striking dinosaurs to have roamed the Earth during the Late Cretaceous period. With its distinctive frill adorned with long, pointed spikes and a single robust horn protruding from its nose, this herbivorous ceratopsian left an unmistakable mark in prehistoric history. Belonging to the same family as the more famous Triceratops, Styracosaurus combined impressive defensive adaptations with a hefty build that helped it survive in a world populated by fearsome predators. This remarkable dinosaur has captivated paleontologists and dinosaur enthusiasts alike since its first discovery in Alberta, Canada in the early 20th century, providing valuable insights into ceratopsian evolution and prehistoric ecosystems.

Discovery and Naming of Styracosaurus

Styracosaurus was first discovered in 1913 by Charles H. Sternberg in the Dinosaur Provincial Park Formation in Alberta, Canada. Lawrence Lambe, a Canadian paleontologist, formally described and named the genus that same year, coining the name Styracosaurus from the Ancient Greek words “styrax” (meaning spike or spear) and “sauros” (meaning lizard). The type species, Styracosaurus albertensis, pays homage to its discovery location in the province of Alberta.

Following this initial finding, several more specimens have been uncovered throughout western North America, particularly in the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, as well as in the state of Montana in the United States. These discoveries have allowed scientists to build a more comprehensive understanding of this remarkable dinosaur’s anatomy and evolutionary significance within the ceratopsian family.

Geological Time Period and Habitat

Styracosaurus inhabited North America during the Late Cretaceous period, specifically between 75.5 and 75 million years ago during what geologists call the Campanian stage. This relatively short geological window means Styracosaurus fossils serve as important index fossils for dating rock formations from this time period. The dinosaur thrived in the lush, subtropical coastal plains that characterized western North America during this era, when the Western Interior Seaway still divided the continent.

Paleoenvironmental studies suggest Styracosaurus lived in a warm, humid climate with abundant vegetation, including cycads, conifers, and early flowering plants that would have provided ample food for these large herbivores. The fossil record indicates these dinosaurs inhabited river valleys and floodplains, likely traveling in herds through these fertile environments that supported diverse dinosaur communities.

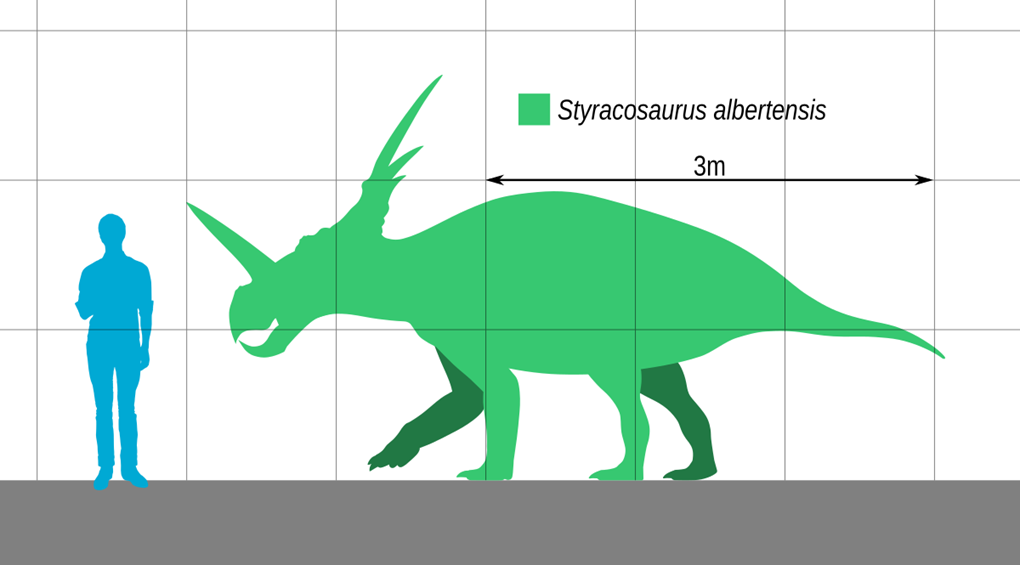

Physical Characteristics and Size

Styracosaurus was a substantial quadrupedal dinosaur, measuring approximately 5.5 meters (18 feet) in length and standing about 1.8 meters (6 feet) tall at the shoulder. Adults typically weighed between 2.7 and 3 tons, comparable to a modern rhinoceros. Its most distinctive feature was undoubtedly the elaborate frill extending from the back of its skull, which measured up to 1 meter (3.3 feet) across and was adorned with six to eight long spikes or horns, some reaching over 50 centimeters (20 inches) in length.

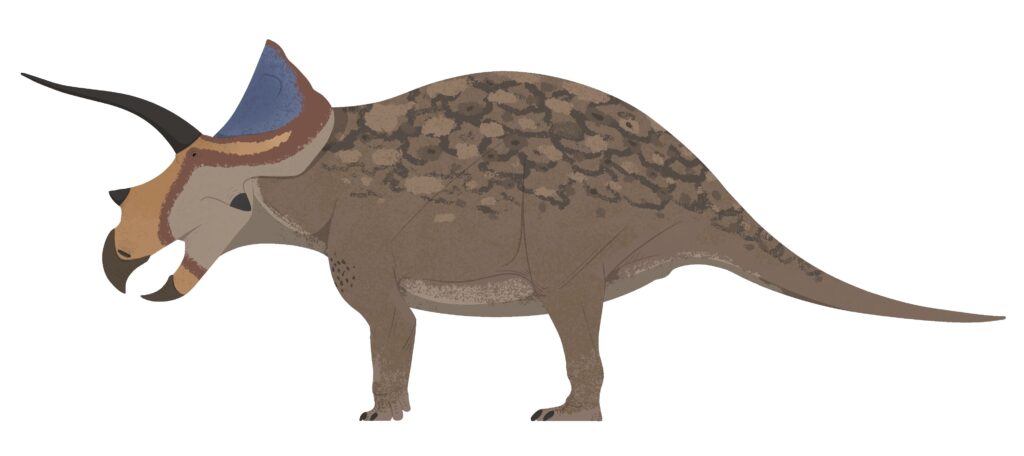

Complementing this impressive headgear was a single large nasal horn that projected forward from its face, measuring up to 60 centimeters (24 inches) in length. The dinosaur possessed a parrot-like beak adapted for cropping vegetation, with a deep, robust skull that housed powerful jaw muscles. Its body was barrel-shaped with sturdy limbs, featuring three-toed feet on the hindlimbs and four-toed feet on the forelimbs, adaptations that effectively supported its considerable weight.

The Magnificent Frill and Horn Configuration

The most iconic feature of Styracosaurus was undoubtedly its elaborate frill and horn arrangement, which has made it instantly recognizable even among the diverse ceratopsian family. The large bony frill projected backward from the skull, forming a shield-like structure that could reach over one meter in diameter. This frill’s perimeter was adorned with four to six long, spear-like spikes on each side, with the longest pairs positioned at the top corners of the frill. These impressive projections, along with the single large nasal horn, created a formidable crown-like appearance that gives Styracosaurus its reputation as one of the most spectacularly ornamented dinosaurs.

Interestingly, studies of fossil specimens reveal slight variations in horn number, size, and arrangement between individuals, suggesting these features may have played roles in species recognition or individual identification. The frill also contained large fenestrae (openings) that would have reduced weight while maintaining structural integrity, a common evolutionary adaptation among ceratopsians.

Classification and Evolutionary Relationships

Styracosaurus belongs to the family Ceratopsidae, a diverse group of horned dinosaurs that inhabited North America and Asia during the Late Cretaceous period. More specifically, it is classified within the subfamily Centrosaurinae, which is characterized by short, broad frills and elaborate nasal horns. This subfamily stands in contrast to the Chasmosaurinae, which includes Triceratops and is known for longer frills and prominent brow horns. Evolutionary studies position Styracosaurus between more primitive centrosaurines like Centrosaurus and more derived forms such as Einiosaurus and Achelousaurus.

Cladistic analyses suggest Styracosaurus shared its most recent common ancestor with Centrosaurus around 77-76 million years ago, with both genera exhibiting similar body plans but divergent frill ornamentation. This evolutionary relationship is particularly evident in the transitional forms found in the fossil record, demonstrating how ceratopsian cranial structures evolved rapidly through relatively small genetic changes, resulting in striking morphological diversity within the family over a relatively short geological timespan.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

Styracosaurus was an obligate herbivore with specialized adaptations for processing tough plant material. Its sharp beak-like mouth was perfectly suited for cropping vegetation, while its batteries of leaf-shaped teeth were arranged in dental batteries that efficiently processed fibrous plant matter. These teeth were continuously replaced throughout the dinosaur’s lifetime, an adaptation necessary due to the significant wear caused by the abrasive plant material in its diet. Paleobotanical evidence suggests Styracosaurus primarily fed on cycads, ferns, and primitive flowering plants that dominated the Late Cretaceous landscape.

Its powerful jaw muscles allowed for complex chewing motions that could break down tough plant fibers, while its relatively low-slung head positioned it well for browsing on low to medium-height vegetation. Some paleontologists theorize that the long nasal horn may have assisted in knocking down taller plants, making them accessible for consumption, though this remains speculative based on the available evidence.

Defensive Adaptations and Predator Interactions

The impressive array of horns and spikes adorning Styracosaurus’s head served as effective defensive weapons against the large theropod predators of the Late Cretaceous, such as Daspletosaurus and Gorgosaurus. When threatened, Styracosaurus could have lowered its head to present its formidable nasal horn toward attackers, while the radiating spikes of its frill would have protected its neck region from predatory lunges. Biomechanical studies suggest the neck muscles of Styracosaurus were robust enough to deliver powerful thrusts with its nasal horn, potentially inflicting serious wounds on attackers.

Trace fossil evidence of healed injuries on some theropod fossils from the same time period might reflect unsuccessful predation attempts on ceratopsians like Styracosaurus. Additionally, these dinosaurs likely benefited from safety in numbers, with fossil evidence suggesting they moved in herds that would have enhanced their collective defense capabilities against predators through increased vigilance and the intimidation factor of multiple horned individuals presenting a unified front.

Social Behavior and Herd Dynamics

Evidence suggests Styracosaurus was a social animal that lived and moved in herds, similar to other ceratopsians. Multiple bone beds containing numerous Styracosaurus individuals of different ages have been discovered, providing compelling evidence for herding behavior. These assemblages indicate that herds may have included dozens or even hundreds of individuals, offering protection against predators and potentially facilitating more efficient foraging across the landscape. Age distribution within these bone beds suggests family groups traveled together, with adults protecting juveniles positioned within the herd’s center.

The elaborate frills and horns likely played significant roles in social interactions, possibly serving as visual display structures for species recognition, sexual selection, or establishing dominance hierarchies within herds. Some paleontologists theorize that male Styracosaurus may have engaged in combat rituals similar to modern horned mammals, using their nasal horns in pushing contests to establish breeding privileges, though such behavior remains speculative without direct fossil evidence of combat injuries specifically attributable to intraspecific conflict.

Growth and Development

The ontogeny (growth and development) of Styracosaurus represents a fascinating aspect of its biology, revealed through fossil specimens of individuals at different life stages. Hatchling Styracosaurus were relatively small, estimated at around 40-50 centimeters in length, and would have lacked the dramatic horn and frill development that characterized adults. As juveniles matured, their distinctive cranial features gradually developed, with the nasal horn emerging first, followed by the progressive growth and elongation of the frill spikes during adolescence.

Growth ring analysis of Styracosaurus bones suggests these animals reached adult size in approximately 10-12 years, representing a relatively rapid growth rate for such large dinosaurs. Interestingly, studies of ceratopsian bone histology reveal these dinosaurs grew more quickly than previously thought, with periods of accelerated growth during favorable environmental conditions. This growth pattern may have helped juvenile Styracosaurus quickly develop the defensive structures necessary for survival, while also indicating these animals possessed a physiology more similar to modern warm-blooded animals than traditional reptiles.

Scientific Significance and Research History

Since its first description in 1913, Styracosaurus has played a pivotal role in advancing our understanding of ceratopsian evolution and dinosaur paleobiology. The exceptionally well-preserved holotype specimen, consisting of a nearly complete skull and partial skeleton, provided early paleontologists with invaluable insights into ceratopsian anatomy.

During the mid-20th century, the discovery of multiple Styracosaurus specimens led researchers like Richard Swann Lull and Charles M. Sternberg to develop important hypotheses about ceratopsian growth and variation. In the 1970s and 1980s, Peter Dodson’s landmark studies on centrosaurine diversity used Styracosaurus as a key example of how dramatic cranial ornamentation could evolve rapidly within dinosaur lineages.

More recently, advanced techniques like CT scanning and histological analysis have revealed details about Styracosaurus’ brain morphology, sensory capabilities, and growth rates. Ongoing research continues to use Styracosaurus as a model organism for understanding broader questions about dinosaur paleoecology, including habitat preferences, feeding adaptations, and the evolutionary pressures that drove the development of their extraordinary defensive and display structures.

Cultural Impact and Representations

With its dramatic appearance, Styracosaurus has captured the public’s imagination since its discovery, becoming a staple in dinosaur popular culture. The dinosaur has been featured prominently in numerous books, films, documentaries, and television programs, including notable appearances in the BBC’s “Walking with Dinosaurs” series and various dinosaur documentaries. Its distinctive silhouette has made it a popular subject for paleoartists, with influential reconstructions by Charles R. Knight, Zdeněk Burian, and Gregory S. Paul helping to shape public perception of this ancient creature over the decades.

Styracosaurus has also found its way into numerous museum exhibits worldwide, with full skeletal mounts and life-sized models attracting visitors at institutions such as the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta and the American Museum of Natural History in New York. In the realm of toys and merchandise, Styracosaurus figures have been produced by major manufacturers since the 1980s, allowing generations of children to encounter this spectacular horned dinosaur through play and fostering early interest in paleontology among young enthusiasts.

Species Diversity and Taxonomic Debates

The taxonomy of Styracosaurus has been subject to ongoing scientific debate and revision as new specimens and analytical methods have emerged. While Styracosaurus albertensis remains the type species and most widely recognized form, several other species have been proposed throughout the genus’s research history. Styracosaurus ovatus, described from Montana in 1930, was distinguished by variations in its frill pattern but has since been reclassified by some researchers as a separate genus, Rubeosaurus. Another proposed species, Styracosaurus parksi, named in 1937, is now generally considered a junior synonym of S. albertensis.

More recently, specimens previously attributed to Styracosaurus have been reassigned to other centrosaurine genera like Einiosaurus and Achelousaurus, reflecting the difficulty in establishing clear taxonomic boundaries in these closely related ceratopsians. These ongoing taxonomic revisions highlight the challenges paleontologists face when working with incomplete fossil material and attempting to determine whether morphological differences represent species-level distinctions, individual variation, sexual dimorphism, or changes related to growth and development.

Paleoecology and Ecosystem Interactions

Styracosaurus inhabited a rich and diverse ecosystem within the Late Cretaceous landscapes of what is now western North America. The Dinosaur Park Formation, where many Styracosaurus fossils have been discovered, represents an ancient coastal plain environment characterized by rivers, floodplains, and swampy areas supporting diverse plant communities.

Styracosaurus shared its habitat with numerous other dinosaur species, including fellow herbivores like the hadrosaur Lambeosaurus, the ankylosaur Euoplocephalus, and other ceratopsians such as Centrosaurus. These herbivores likely occupied different ecological niches to reduce competition, with Styracosaurus possibly specializing in mid-level vegetation, while hadrosaurs focused on lower browse and other ceratopsians targeted different plant types or feeding zones.

The ecosystem also included apex predators like Gorgosaurus and Daspletosaurus that would have preyed upon Styracosaurus, particularly targeting young or isolated individuals. Alongside dinosaurs, the environment hosted a diverse community of other vertebrates, including turtles, crocodilians, mammals, and pterosaurs, as well as numerous invertebrates and plant species, creating a complex web of ecological interactions that paleontologists continue to reconstruct through multidisciplinary research approaches.

Extinction and Legacy

Styracosaurus disappeared from the fossil record approximately 75 million years ago, well before the end-Cretaceous mass extinction that claimed the last non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Its extinction appears to have been part of the normal turnover of ceratopsian species rather than resulting from a catastrophic event, with its ecological niche being filled by subsequent centrosaurine genera like Pachyrhinosaurus and Einiosaurus.

This pattern of relatively rapid evolutionary turnover characterized ceratopsian dinosaurs throughout the Late Cretaceous, with many genera existing for relatively brief geological intervals before being replaced by new forms. Though extinct for 75 million years, Styracosaurus has left an enduring scientific legacy through the fossils it left behind, which continue to provide valuable data about dinosaur evolution, paleoecology, and the ancient environments of North America.

Its striking appearance has also secured its place in popular culture as one of the most recognizable dinosaurs, inspiring scientific curiosity and wonder in generations of paleontology enthusiasts. In this way, Styracosaurus continues to contribute to our understanding of Earth’s prehistoric past while stimulating ongoing interest in the remarkable diversity of life that has inhabited our planet throughout its long history.

Conclusion

Styracosaurus remains one of paleontology’s most visually striking and scientifically significant dinosaurs. From its impressive crown of horns to its social behaviors and ecological adaptations, this ceratopsian offers a fascinating window into life during the Late Cretaceous period. As research methods continue to advance, our understanding of this remarkable creature grows ever more sophisticated, revealing a complex animal perfectly adapted to its prehistoric environment.