The popular imagination often places dinosaurs in lush, tropical jungles—a vision reinforced by movies like Jurassic Park. However, paleontological evidence reveals a far more diverse range of habitats where these magnificent creatures thrived for over 165 million years. From sprawling swamplands to arid savannas and shallow inland seas, dinosaurs adapted to an astonishing variety of environments across a dramatically different Earth. Their fossil remains tell stories not just of the animals themselves, but of ancient ecosystems that bear little resemblance to our modern world. By examining where dinosaurs actually lived, we gain crucial insights into their behaviors, adaptations, and the environmental conditions that shaped their evolution throughout the Mesozoic Era.

The Mesozoic World: An Earth Unlike Our Own

During the Mesozoic Era (252-66 million years ago), Earth’s landmasses were arranged quite differently than they are today. The supercontinent Pangaea began breaking apart, creating new coastlines, mountain ranges, and inland basins that dinosaurs would occupy. Global temperatures were significantly warmer, with minimal polar ice and sea levels often much higher than present day. The atmosphere contained notably more oxygen and carbon dioxide, supporting different plant communities than those familiar to us. These fundamental geographical and climatic differences created ecosystems without modern analogs—environments where dinosaurs could evolve specialized adaptations to exploit particular niches. Understanding this alien Earth is essential to properly contextualizing dinosaur habitats rather than simply projecting modern environments backward in time.

Swampland Titans: The Habitat of Many Iconic Dinosaurs

Extensive swamplands covered significant portions of Mesozoic continents, particularly during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. These wetland environments, with their abundant water and vegetation, provided ideal habitats for many famous dinosaur species. The Morrison Formation of western North America, home to giants like Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, and Stegosaurus, preserves evidence of vast floodplains with seasonal wetlands and oxbow lakes. Similar environments in the Wealden Group of England supported Iguanodon and other ornithopods. The rich plant matter in these swampy regions could sustain herds of massive herbivores, while the varied terrain created microhabitats where different dinosaur species could coexist. Their remains were often quickly buried in waterlogged sediments, creating exceptional preservation conditions that explain why we find so many fossils from these environments.

Coastal Plains and Delta Environments

Coastal deltas and plains represented some of the most productive and densely populated dinosaur habitats. The Hell Creek Formation of North America, famous for Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops, preserves a vast coastal floodplain that existed during the late Cretaceous. These environments offered diverse vegetation and abundant water, supporting complex food webs. The interplay between freshwater and marine influences created varied microhabitats within relatively small geographical areas. Rivers constantly deposited new sediment, burying remains and creating the ideal conditions for fossilization. Evidence suggests these coastal plains supported some of the highest dinosaur population densities, with varied herbivore communities supporting multiple large predator species. The transitional nature of these environments also meant that dinosaurs living here had to adapt to seasonal flooding and changing coastlines over time.

The Surprising Prevalence of Arid Environments

Contrary to popular depictions, many dinosaurs thrived in surprisingly dry environments. The Gobi Desert of Mongolia has yielded extraordinary fossils of Protoceratops, Velociraptor, and many other species that adapted to arid conditions during the Cretaceous. The Bahariya Formation in Egypt, home to the massive predator Spinosaurus, shows evidence of seasonal aridity punctuated by wetter periods. These dinosaurs developed specialized adaptations for water conservation and foraging in sparse vegetation. The Ischigualasto Formation in Argentina preserves some of the earliest dinosaurs, like Eoraptor, in what was then a seasonally dry floodplain with periodic droughts. Fossils from these environments often show evidence of mass mortality events during particularly severe dry spells, with animals congregating around diminishing water sources. Their ability to survive in these challenging conditions demonstrates the remarkable adaptability that helped dinosaurs dominate terrestrial ecosystems for so long.

Savannas and Open Woodlands

Savanna-like environments, characterized by open grasslands interspersed with trees, became increasingly common during the Cretaceous period. While true grasses hadn’t yet evolved, ferns and other low-growing plants created analogous open landscapes. The Two Medicine Formation in Montana preserves a community including the duck-billed Maiasaura in what was then a relatively open woodland environment with seasonal rainfall. These habitats were particularly conducive to herding behavior among herbivorous dinosaurs, as evidenced by multiple bonebeds containing specimens of various ages. Predators in these environments often evolved for speed and endurance rather than ambush tactics. The savanna-like settings also provided minimal cover, potentially encouraging the evolution of display features like crests and frills that served communication functions within herds. These open environments would eventually become more dominant as flowering plants diversified later in the Cretaceous period.

Inland Seas: Dinosaurs of the Shallow Marine Environment

Throughout the Mesozoic Era, rising sea levels frequently created vast inland seas that divided continents. The Western Interior Seaway split North America from present-day Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic during the Cretaceous, creating thousands of miles of new coastline. While not true marine animals, many dinosaur species adapted to life along these seaway margins. Fossils of hadrosaurs and ceratopsians are occasionally found in marine deposits, suggesting they lived near enough to these waters to be occasionally swept out to sea. Some specialized dinosaurs like the fish-eating Spinosaurus show adaptations specifically for exploiting aquatic resources in these environments. The inland seas created corridors for marine life but barriers for land animals, influencing dinosaur evolution and distribution patterns across continents. These seaways also generated unique coastal microclimates that supported distinctive plant communities and the dinosaurs that fed on them.

Polar Dinosaurs: Life in Extreme Latitudes

Perhaps most surprising to casual dinosaur enthusiasts is the abundance of fossils discovered in ancient polar regions. The North Slope of Alaska has yielded numerous dinosaur species, including Edmontosaurus and Troodon, that lived well above the Arctic Circle during the Cretaceous. Australia’s Dinosaur Cove preserves polar dinosaurs from the southern hemisphere, including small ornithopods that survived the dark Antarctic winters. While these regions were warmer than today’s poles due to higher global temperatures, they still experienced months of darkness and potential seasonal freezing. Evidence suggests some polar dinosaurs had enhanced vision for low-light conditions and possibly higher metabolic rates to withstand cooler temperatures. Some species may have migrated seasonally, while others apparently remained year-round, possibly entering torpor during the darkest months. These polar adaptations challenge the notion that dinosaurs were strictly cold-intolerant reptiles and suggest sophisticated physiological adaptations.

Mountain-Dwelling Dinosaurs

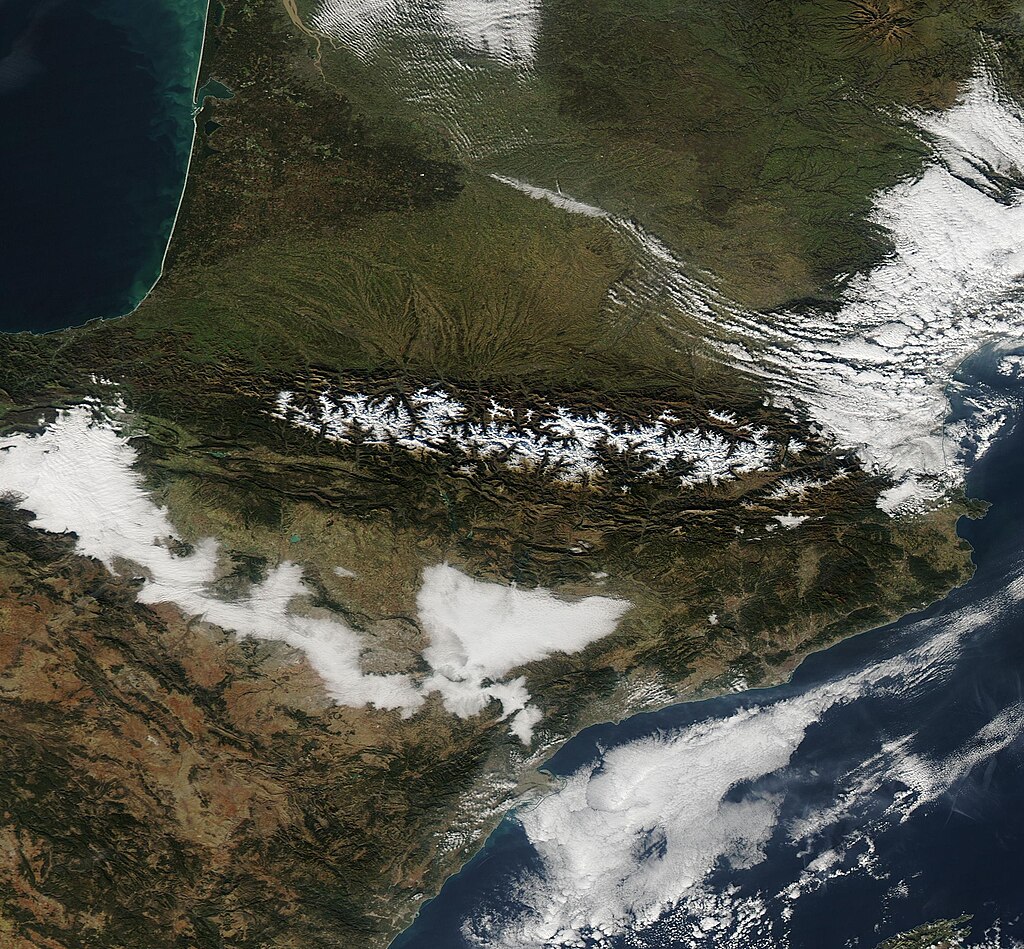

Mountainous regions represented another challenging habitat colonized by certain dinosaur species. The Pyrenees region between France and Spain has yielded fossils of titanosaur sauropods that appear to have inhabited higher elevation environments during the late Cretaceous. The Djadochta Formation in Mongolia preserves dinosaurs like Oviraptor that lived in a highland desert environment with significant topographical relief. These upland habitats typically offered different vegetation and climate conditions than the surrounding lowlands, creating specialized niches. Mountain-dwelling dinosaurs often show adaptations for traversing uneven terrain, including more compact body forms in some cases. The isolation created by mountain ranges could also drive speciation events, as populations became separated and evolved independently. Despite the challenges of preservation in these environments due to erosion rather than deposition, paleontologists continue finding evidence that dinosaurs successfully exploited even these challenging habitats.

Island Habitats and Insular Dwarfism

As the supercontinents fragmented throughout the Mesozoic, numerous islands were created that became evolutionary laboratories for dinosaur adaptation. The phenomenon of insular dwarfism—where large animals evolve smaller body sizes on islands with limited resources—is well-documented among dinosaurs. The late Cretaceous Hațeg Island in present-day Romania was home to dwarf titanosaurs like Magyarosaurus, which reached only a fraction of their mainland relatives’ size. Similar patterns have been observed with Europasaurus from isolated islands in what is now Germany. These island environments typically supported less diverse but highly specialized dinosaur communities. Isolation protected these populations from mainland competitors and predators but also limited genetic diversity. Island-dwelling dinosaurs often developed unique characteristics in response to their restricted habitats, making them valuable case studies in evolutionary processes. Their fossils provide crucial evidence of how quickly dinosaurs could adapt to changing environmental conditions.

Forests and Woodlands: Not All Were Tropical

While forests were indeed common dinosaur habitats, they were far more diverse than the stereotypical tropical jungles depicted in popular media. Conifer forests dominated many high-latitude regions, as evidenced by the abundant remains of pine relatives found alongside dinosaur fossils in formations like the Prince Creek Formation in Alaska. The Yixian Formation in China preserves dinosaurs like Microraptor and Psittacosaurus in a temperate forest setting with seasonal variations. During the early Jurassic, forests were dominated by cycads, ginkgoes, and conifers rather than flowering plants, creating very different understory conditions than modern forests. Evidence suggests some dinosaurs, particularly smaller species, were well-adapted for life among trees, with some even showing arboreal adaptations. The forest floor environment, with its complex three-dimensional structure, offered numerous microhabitats that could support high dinosaur diversity within relatively small areas. These woodland settings evolved significantly throughout the Mesozoic as flowering plants began their rise to dominance.

Volcanic Landscapes

Active volcanism was a feature of many landscapes throughout the Mesozoic, creating both hazards and opportunities for dinosaur communities. The Two Medicine Formation preserves dinosaurs that lived in the shadow of an active volcanic arc, with ash falls periodically impacting the region. These volcanic soils, once weathered, created exceptionally fertile grounds that supported abundant plant life and, consequently, diverse dinosaur communities. Catastrophic eruptions occasionally resulted in mass mortality events, such as those preserved in the Jianshangou Bed in northeastern China, where dinosaurs and other animals were killed and exceptionally preserved by volcanic ash falls. Volcanically active regions typically featured diverse topography, from ash plains to highlands, supporting varied dinosaur communities within relatively small geographical areas. The fossils preserved in volcanic contexts often show exceptional preservation due to rapid burial, providing some of our most detailed insights into dinosaur anatomy and appearance.

Seasonal Changes and Migration Patterns

Many dinosaur habitats experienced significant seasonal changes that influenced dinosaur behavior and distribution. Growth rings in fossil bones, similar to tree rings, indicate periods of abundant resources alternating with more challenging conditions. The Judith River Formation in Montana preserves evidence suggesting that hadrosaurs and ceratopsians may have undertaken seasonal migrations to follow optimal feeding conditions. Some high-latitude dinosaurs show adaptations for living in environments with extreme seasonal variation in daylight, including enhanced vision and possibly specialized metabolic adaptations. Nesting sites often show evidence of seasonal usage, suggesting dinosaurs timed reproduction to coincide with optimal conditions for raising young. Seasonal resource fluctuations likely influenced herd behavior, with some evidence suggesting dinosaurs formed larger aggregations during certain seasons and dispersed during others. Understanding these seasonal patterns is crucial for interpreting dinosaur behavior and ecology beyond the simplified depictions common in popular media.

The Evolution of Habitats Through the Mesozoic

Dinosaur habitats weren’t static but evolved dramatically throughout the Mesozoic Era’s 165 million years. The early Triassic world, where dinosaurs first emerged, was dominated by seed ferns and conifers, with true flowering plants completely absent. By the late Cretaceous, angiosperms (flowering plants) had diversified explosively, transforming landscapes and creating new feeding opportunities for herbivorous dinosaurs. Climate fluctuated significantly throughout this span, with evidence for several warming and cooling events that would have shifted habitat boundaries. The gradual breakup of Pangaea created new coastlines, inland seas, and mountain ranges, fragmenting once-continuous habitats and driving speciation. Some dinosaur groups show clear habitat preferences that evolved over time, such as sauropods transitioning from widespread distribution in the Jurassic to primarily low-latitude environments by the late Cretaceous. Understanding these dynamic habitat changes is essential for interpreting the evolutionary history of different dinosaur lineages and their adaptations.

How We Reconstruct Ancient Habitats

Paleontologists use multiple lines of evidence to reconstruct the environments where dinosaurs lived. Sedimentology—the study of ancient sediments—reveals the physical conditions where fossils were deposited, distinguishing between river channels, floodplains, dune fields, or shallow seas. Plant fossils found alongside dinosaur remains provide crucial information about the vegetation that supported herbivorous species. Fossil pollen, extremely resistant to decay, offers insights into plant communities even when larger plant fossils are absent. Chemical analyses of fossil soils (paleosols) can indicate ancient rainfall patterns, temperature ranges, and seasonality. Microscopic analysis of fossil teeth can reveal wear patterns indicating the types of vegetation consumed. Isotope studies of fossil bones and teeth provide clues about diet, water sources, and even body temperatures. By combining these various approaches, scientists continue refining our understanding of the diverse environments that dinosaurs inhabited throughout their long evolutionary history.

Modern Misconceptions vs. Paleontological Reality

Popular media have significantly shaped public perception of dinosaur habitats, often inaccurately. The persistent image of dinosaurs primarily inhabiting steamy jungles contradicts the evidence that they thrived across nearly every terrestrial environment from poles to equator. Another common misconception is depicting dinosaurs from different time periods and continents living together, when in reality, Tyrannosaurus and Stegosaurus were separated by a greater time span than Tyrannosaurus and humans. Modern depictions often fail to capture the truly alien nature of Mesozoic landscapes, with their different atmospheric composition, unfamiliar plant communities, and unique geological features. Contemporary reconstructions increasingly incorporate paleobotanical evidence to accurately portray the plants that would have surrounded dinosaurs rather than using anachronistic modern species. Perhaps most importantly, the fossil record shows dinosaurs were not evolutionary failures but highly successful animals that dominated terrestrial ecosystems for far longer than mammals have existed, adapting to countless environmental changes before their extinction.

Conclusion

The environments where dinosaurs lived were remarkably diverse, from parched deserts to lush wetlands, from polar forests to tropical coastlines. This environmental flexibility helps explain their extraordinary evolutionary success over millions of years. As paleontological methods become increasingly sophisticated, our understanding of these ancient habitats continues to improve, revealing dinosaurs as supremely adaptable creatures that could exploit almost any terrestrial niche. Far from the simplistic portrayal of dinosaurs in steamy jungles, the fossil record shows they conquered virtually every habitat available to them—a testament to their remarkable adaptability and evolutionary success. By accurately reconstructing these environments, we gain not just a clearer picture of dinosaur biology and behavior, but also valuable insights into how ecosystems respond to environmental changes over geological timescales.