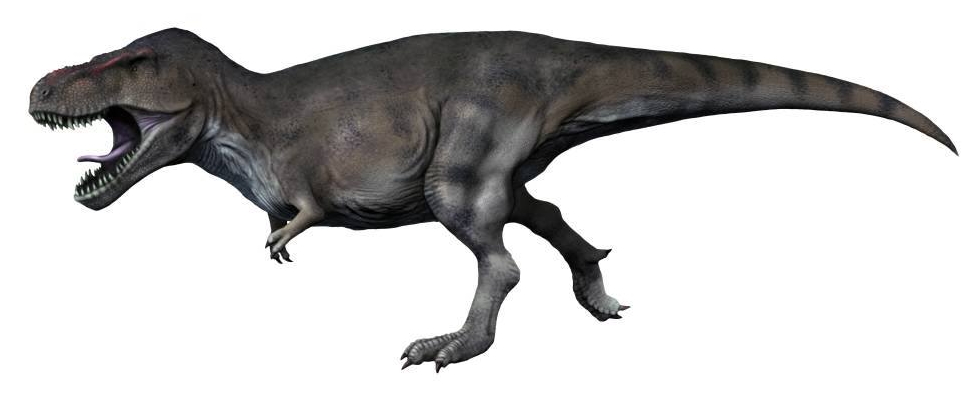

The prehistoric world was dominated by some of the most fearsome predators ever to walk the Earth. Among these ancient titans, Tyrannosaurus rex and Spinosaurus aegyptiacus stand out as two of the most formidable carnivorous dinosaurs. Both were apex predators in their respective environments, equipped with terrifying physical attributes and hunting capabilities. For decades, paleontologists and dinosaur enthusiasts have debated which of these magnificent beasts would emerge victorious in a hypothetical confrontation. This article explores the anatomical features, hunting strategies, and environmental adaptations of both dinosaurs to analyze who might have had the upper hand in a prehistoric showdown.

The Physical Giants: Size Comparison

When comparing these prehistoric titans, size matters significantly. Tyrannosaurus rex typically measured around 40 feet in length and stood about 12 feet tall at the hip, weighing approximately 8-10 tons. Spinosaurus, however, holds the title of the largest known carnivorous dinosaur, reaching lengths of 45-50 feet, standing 16-20 feet tall, and weighing an estimated 7-20 tons, depending on the specimen. Recent fossil discoveries suggest Spinosaurus was even larger than previously thought, with a longer body and more substantial mass. The size advantage clearly goes to Spinosaurus, giving it a potential edge in a confrontation simply through intimidation and reach. However, size alone doesn’t determine the outcome of predatory encounters, as other factors, including strength, speed, and specialized adaptations, play crucial roles.

Jaw Power: Bite Force Analysis

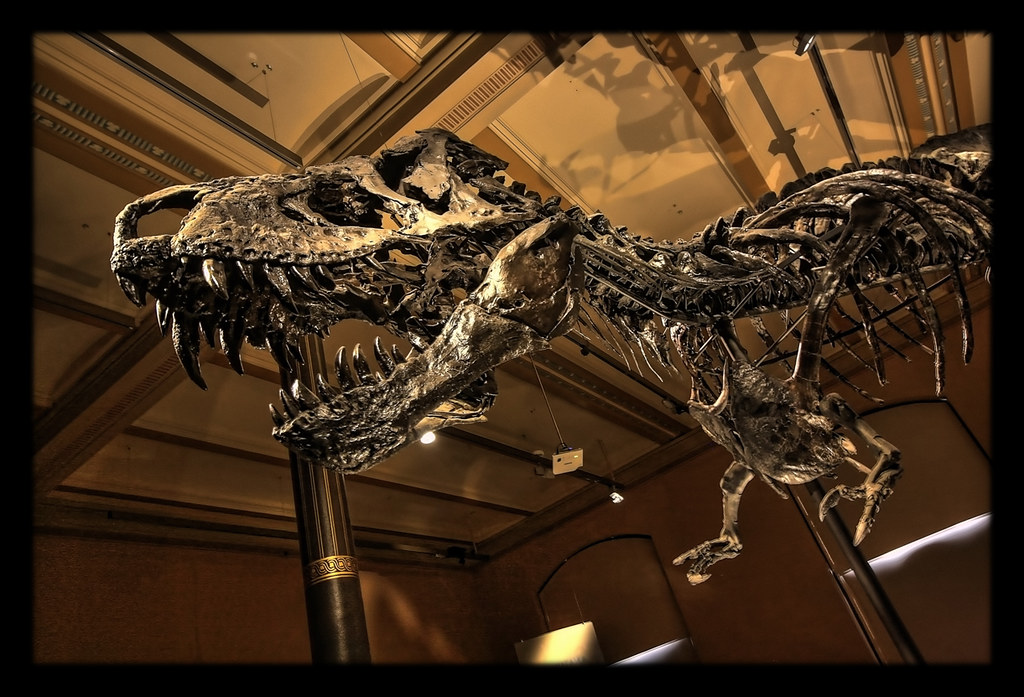

Tyrannosaurus rex possessed what may have been the most powerful bite of any land animal in Earth’s history. Scientific studies estimate its bite force at a staggering 12,800 pounds per square inch, capable of crushing bones and tearing through thick hide with ease. This incredible force was complemented by banana-sized serrated teeth designed for cutting and crushing, allowing T. rex to inflict devastating wounds on prey and potential rivals. Spinosaurus, while formidable, had a notably different jaw structure that evolved primarily for fishing—its long, narrow snout housed conical teeth better suited for grasping slippery prey rather than delivering bone-crushing bites. Biomechanical analyses suggest Spinosaurus had a bite force significantly less powerful than T. rex, estimated at around 4,200 pounds per square inch. In terms of pure bite power and devastating potential, T. rex clearly held the advantage, possessing a specialized killing tool that could potentially end a confrontation with one well-placed bite.

Arms and Claws: Forelimb Comparison

The forelimbs of these two predators differed dramatically in both size and functionality. T. rex famously possessed extremely short arms, measuring only about 3 feet long, with two-fingered hands ending in short claws. Despite their diminutive size, these arms were surprisingly muscular, potentially capable of exerting up to 400 pounds of force, though their practical utility in combat remains debated among paleontologists. Spinosaurus, contrastingly, boasted much longer, more robust forelimbs ending in three-fingered hands with large, curved claws estimated to be around 12 inches in length. These powerful forelimbs likely played a significant role in hunting, possibly used for grasping prey, swimming, and defense. The functional advantage in forelimb capability clearly belongs to Spinosaurus, providing it with an additional weapon system that could potentially inflict serious damage in a close-quarters confrontation while keeping its vital head region at a safer distance from an opponent’s jaws.

Speed and Mobility: Who Was More Agile?

Mobility would play a crucial role in any prehistoric confrontation between these titans. T. rex, despite its massive bulk, was surprisingly swift, with most scientific estimates suggesting it could reach speeds between 12-25 mph during short bursts. Its powerful hind legs were built for pursuit, and its body was balanced by a massive tail that served as a counterweight. Spinosaurus, with its semi-aquatic adaptations, was likely slower on land, with estimates suggesting terrestrial speeds of 5-12 mph. Its center of gravity and leg proportions were optimized for a different locomotion style, particularly swimming. Recent studies of Spinosaurus tail vertebrae indicate it possessed a large, paddle-like tail perfect for aquatic propulsion, making it an excellent swimmer but potentially compromising its land speed. In a terrestrial confrontation, T. rex would likely have the advantage in terms of speed and agility, potentially able to outmaneuver the more aquatically-adapted Spinosaurus on dry land.

Habitat Specialization: Terrain Advantages

The environments these predators evolved to dominate significantly influenced their physical adaptations and hunting strategies. T. rex thrived in the diverse landscapes of what is now western North America during the Late Cretaceous period, hunting in forests, open plains, and river valleys. It was a purely terrestrial predator, evolved for pursuing and overpowering large dinosaurs in these environments. Spinosaurus, however, inhabited the lush river systems of North Africa, evolving specialized adaptations for a semi-aquatic lifestyle. Recent fossil evidence, including dense bones for buoyancy control and that paddle-like tail, strongly suggests Spinosaurus spent considerable time in water pursuing aquatic prey. This habitat specialization means a theoretical confrontation’s location would significantly impact the outcome—Spinosaurus would have a distinct advantage in or near water, where its swimming capabilities could be leveraged, while T. rex would dominate in open terrestrial environments where its speed and power could be fully utilized.

Hunting Strategies: Predatory Techniques

The hunting strategies employed by these dinosaurs reflected their anatomical specializations and environmental adaptations. T. rex was likely an ambush predator that relied on relatively short bursts of speed to overtake prey, using its incredible bite force to deliver fatal wounds. Evidence suggests it hunted large herbivorous dinosaurs, potentially working alone or in small family groups. Its huge olfactory bulbs indicate an exceptional sense of smell for locating prey and carrion over vast distances. Spinosaurus employed a dramatically different hunting strategy, specializing in catching fish and other aquatic creatures. Its crocodile-like snout, pressure-sensitive receptors, and conical teeth were perfectly adapted for detecting and capturing slippery aquatic prey. Recent studies of its bone density suggest it could submerge to pursue fish actively. These contrasting hunting specializations mean each dinosaur was optimized for very different prey and techniques, with T. rex evolved for bringing down large terrestrial animals while Spinosaurus specialized in aquatic hunting—a difference that would significantly influence any potential confrontation.

Timeline Disparity: Did They Ever Meet?

Despite popular imagination pitting these dinosaurs against each other, Tyrannosaurus rex and Spinosaurus existed at different times and places, making a natural encounter between them impossible. Spinosaurus lived during the mid-Cretaceous period, approximately 112 to 97 million years ago, primarily in what is now North Africa. T. rex appeared much later, thriving in western North America during the late Cretaceous period from about 68 to 66 million years ago, just before the mass extinction event that wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs. This temporal separation of nearly 30 million years means these species never encountered each other in the wild. Additionally, they evolved on different continents separated by ancient seas, further ensuring they never competed for territory or resources. This geological and temporal reality underscores that any discussion of combat between these species remains purely hypothetical, based on comparative anatomy and biomechanical analyses rather than historical possibility.

Sensory Capabilities: Detection and Awareness

The sensory adaptations of these predators played a crucial role in their hunting success and would similarly influence any theoretical confrontation. T. rex possessed exceptional senses, particularly its sense of smell, with olfactory bulbs larger than any other dinosaur relative to its brain size. Its vision was also highly developed, with forward-facing eyes providing excellent depth perception and visual acuity estimated to be 13 times that of humans. T. rex also had specialized sensory organs in its jaw that may have helped it detect prey movement. Spinosaurus likely had sensory adaptations more similar to modern crocodilians, with pressure receptors in its snout that would have allowed it to detect movement in water. Its eyes were positioned higher on its skull, providing better visibility while partially submerged. These different sensory specializations meant each dinosaur excelled at detecting prey in its preferred habitat, with T. rex having superior terrestrial awareness while Spinosaurus was better adapted to detecting movement in aquatic environments.

Defensive Capabilities: Protection Mechanisms

Both dinosaurs evolved different protective adaptations suited to their lifestyles and predatory strategies. T. rex relied primarily on its intimidating size, speed, and devastating bite force as both offensive and defensive mechanisms. Its thick skull could withstand tremendous forces, and some paleontologists suggest T. rex engaged in head-pushing contests with rivals, indicating robust cranial defenses. Despite lacking traditional armor, its sheer mass and power served as effective deterrents against most threats. Spinosaurus featured more specialized defensive adaptations, including its most distinctive feature—the enormous sail on its back formed by elongated neural spines. While primarily theorized to serve thermoregulatory or display purposes, this sail may have made Spinosaurus appear even larger to potential threats. Its crocodile-like anatomy also suggests it could potentially retreat to water when threatened on land. In terms of pure defensive capability, both dinosaurs had effective, though different, mechanisms for protection, with T. rex relying on raw power and Spinosaurus utilizing specialized adaptations and environmental advantages.

Social Behavior: Lone Hunters or Pack Predators?

The social behaviors of these prehistoric predators remain subjects of ongoing research and debate, with implications for how they might have approached confrontations. Evidence suggests T. rex may have exhibited more complex social behaviors than previously thought. Some fossil sites show multiple T. rex individuals preserved together, potentially indicating family groups or loose packs. This social dimension might have enhanced T. rex’s hunting capabilities and territorial defense. Spinosaurus, based on current evidence, appears to have been primarily a solitary hunter, specially adapted for fishing and aquatic prey capture rather than cooperative hunting. Its lifestyle, centered around rivers and waterways where it specialized in catching fish, aligns with solitary hunting behaviors seen in many modern piscivorous predators. These different social structures would influence a theoretical confrontation—a solitary Spinosaurus encountering even a pair of T. rex would face significant disadvantages, while a one-on-one encounter might favor the larger Spinosaurus depending on the environment.

Scientific Evidence: Fossil Clues to Combat

Fossil evidence provides intriguing insights into how these predators might have behaved in confrontational situations. T. rex fossils frequently show signs of intraspecific combat—bite marks on facial bones and healed injuries suggesting these dinosaurs engaged in face-biting behaviors with other T. rex individuals. These findings indicate T. rex was accustomed to direct confrontation and had evolved to both deliver and withstand powerful bites. Spinosaurus fossils reveal different patterns, showing adaptations primarily focused on aquatic specialization rather than combat with large terrestrial predators. The 2020 discovery of a remarkably complete Spinosaurus tail confirmed its aquatic lifestyle, suggesting it evolved to avoid direct competition with purely terrestrial predators by exploiting water resources. Stress analyses of both dinosaurs’ skeletons indicate T. rex was built to withstand the forces involved in taking down struggling large prey, while Spinosaurus showed adaptations better suited for handling the lateral stresses of swimming and catching fish. These fossil clues suggest T. rex evolved in an environment where combat with large opponents was common, potentially giving it an experiential advantage in a theoretical confrontation.

The Final Verdict: Environmental Context Is Key

When analyzing this hypothetical prehistoric showdown, environmental context emerges as perhaps the most decisive factor. In a terrestrial environment away from water, T. rex would likely have the advantage. Its superior bite force, terrestrial speed, and specialized sensory adaptations for hunting on land would make it a formidable opponent. The T. rex’s thick skull and powerful neck muscles were specifically evolved for delivering and withstanding massive forces during combat with large prey and rivals. In or near water, however, the advantage would shift dramatically to Spinosaurus. Its swimming capabilities, longer forelimbs with massive claws, and sheer size would become significant advantages in an aquatic environment where T. rex would struggle with mobility. Spinosaurus could potentially use hit-and-run tactics, striking from the water before retreating to safety. This environmental dependency highlights how specialized these apex predators were for their respective niches—T. rex as the ultimate terrestrial predator and Spinosaurus as a masterfully adapted semi-aquatic hunter.

Modern Scientific Perspectives: How Research Has Evolved

Our understanding of these magnificent predators continues to evolve with new fossil discoveries and analytical techniques. Recent research has dramatically revised our conception of Spinosaurus, transforming it from what was once thought to be simply a large terrestrial predator with a sail to a highly specialized semi-aquatic dinosaur with a paddle-like tail and dense bones for buoyancy control. These discoveries have fundamentally changed how paleontologists view potential interactions between large theropods. Similarly, studies of T. rex have revealed a more complex picture of its capabilities, with research into its sensory abilities, growth patterns, and potential social behaviors painting a picture of a highly sophisticated predator rather than a simple brute. Modern biomechanical analyses using computer modeling have allowed scientists to better understand the structural limits and capabilities of these animals, from bite force to movement speed. These scientific advances remind us that our understanding is constantly evolving, and future discoveries may further alter our perspective on how these magnificent predators lived and how they might have interacted had time and geography allowed their paths to cross.

In this hypothetical prehistoric showdown, the winner would ultimately be determined by the specific circumstances of the encounter. T. rex and Spinosaurus evolved as supremely adapted predators for different environments and prey types, each dominant in their respective niches. Rather than declaring an absolute victor, perhaps the most scientifically accurate conclusion is an appreciation for the remarkable evolutionary adaptations that made each of these dinosaurs perfectly suited to their own environments and lifestyles, representing different but equally impressive expressions of predatory excellence in the ancient world.