In the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 70 million years ago, a fearsome predator roamed the landscapes of Mongolia and China. Tarbosaurus bataar, often referred to as Asia’s Tyrant Lizard, dominated the ecosystem as the apex predator of its time. Closely related to the more famous Tyrannosaurus rex of North America, Tarbosaurus represents one of Asia’s most significant dinosaur discoveries. This massive theropod has fascinated paleontologists since its first discovery in the 1940s, offering crucial insights into dinosaur evolution and the distinct characteristics of Asian dinosaur fauna. Through decades of research and remarkable fossil discoveries, we’ve pieced together the story of this magnificent prehistoric predator that once ruled the ancient Asian continent.

The Discovery of Tarbosaurus

The scientific journey of Tarbosaurus began in 1946 during a Soviet-Mongolian paleontological expedition to the Gobi Desert. Led by Russian paleontologist Evgeny Maleev, the team unearthed several large theropod specimens in the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. Initially, Maleev classified these findings as several different species, including “Tyrannosaurus bataar,” reflecting their similarity to the North American T. rex. It wasn’t until the 1960s that further analysis by paleontologist Anatoly Rozhdestvensky suggested all these specimens represented a single species at different growth stages. This reclassification established the dinosaur as its genus – Tarbosaurus – derived from the Greek “tarbo,” meaning “terror,” and “sauros,” meaning “lizard.” The discovery opened a new chapter in our understanding of Asian dinosaurs and their relationship to their North American counterparts.

Anatomical Features and Size

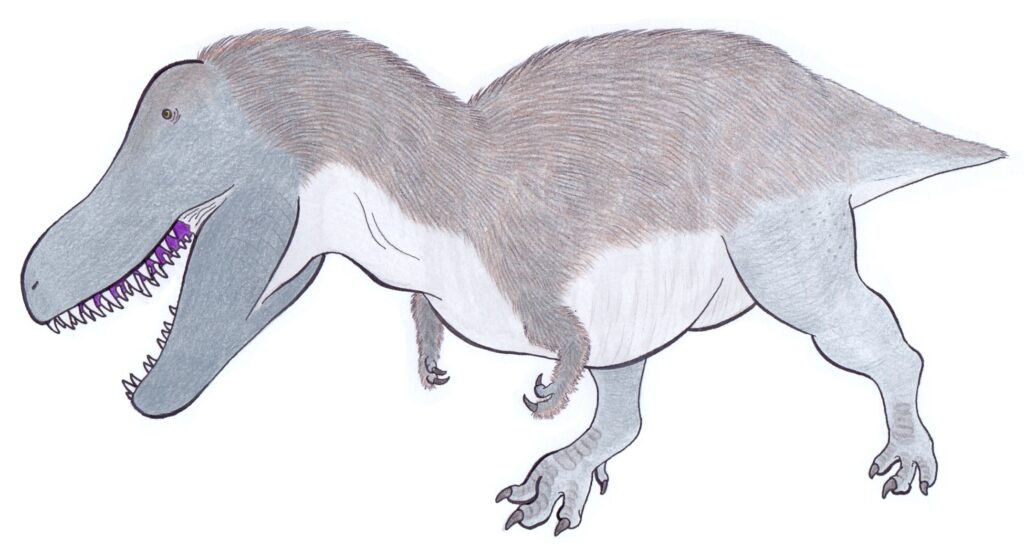

Tarbosaurus was a massive bipedal carnivore that shared many characteristics with its close relative, Tyrannosaurus rex. Adult specimens reached lengths of 10-12 meters (33-39 feet) and stood approximately 4 meters (13 feet) tall at the hip, with weight estimates ranging from 4 to 6 tons. Its enormous skull, measuring up to 1.3 meters (4.3 feet) in length, featured about 60 large, serrated teeth designed for crushing bone and tearing flesh. Despite its overall similarity to T. rex, Tarbosaurus had several distinctive features, including a narrower skull, smaller and more numerous teeth, and proportionally smaller forelimbs with two functional digits instead of three. Its powerful hind limbs and muscular tail provided balance for its massive head, while its relatively stiff neck allowed for powerful biting forces. These anatomical adaptations made Tarbosaurus perfectly suited for its role as the dominant predator in its ecosystem.

Habitat and Geographic Range

Tarbosaurus inhabited what is now the Gobi Desert region of Mongolia and parts of northern China during the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 70-65 million years ago. Unlike the arid desert conditions of today, this region during the Late Cretaceous was considerably more lush and hospitable. Paleoenvironmental studies indicate that the Nemegt Formation, where most Tarbosaurus fossils have been discovered, featured a network of river systems, floodplains, and forest areas that supported diverse plant and animal life. The climate was likely seasonally wet and dry, rather than permanently arid. This rich ecosystem provided Tarbosaurus with abundant prey opportunities and suitable nesting grounds. Fossil evidence suggests that Tarbosaurus had a relatively restricted geographic range compared to some other tyrannosaurs, indicating it was specifically adapted to the unique environmental conditions of central Asia during this period.

The Tyrannosaur Family Tree

Tarbosaurus belongs to the family Tyrannosauridae, a group of large carnivorous theropods that dominated the Northern Hemisphere during the Late Cretaceous period. Within this family, Tarbosaurus is classified in the subfamily Tyrannosaurinae alongside Tyrannosaurus rex, with whom it shares many anatomical similarities. Phylogenetic analyses suggest that Tarbosaurus and Tyrannosaurus were sister taxa, having diverged from a common ancestor perhaps 5-10 million years before their respective reigns. This close evolutionary relationship explains their many similarities, though each evolved specific adaptations to their respective environments. Other members of the tyrannosaur family include Albertosaurus, Daspletosaurus, and Gorgosaurus from North America, and Zhuchengtyrannus from Asia. The study of Tarbosaurus has been crucial in understanding tyrannosaur evolution and biogeography, particularly how these apex predators spread and diversified across Asia and North America during the Late Cretaceous, when these continents were occasionally connected by land bridges.

Hunting and Feeding Behavior

Tarbosaurus was unquestionably the apex predator of its ecosystem, equipped with formidable hunting capabilities. Biomechanical studies of its skull reveal it possessed one of the most powerful bites of any terrestrial predator, capable of crushing bone and tearing through tough tissues. Unlike smaller, more agile predators, Tarbosaurus likely relied on ambush tactics rather than prolonged chases, using its acute senses to detect prey before launching devastating attacks. Its primary prey would have included large herbivorous dinosaurs such as hadrosaurs, sauropods, and possibly ankylosaurs that shared its habitat. Particularly telling are bite marks discovered on herbivore fossils that match Tarbosaurus tooth patterns. Interestingly, the reduced forelimbs of Tarbosaurus suggest they played minimal roles in hunting, with the massive jaws doing most of the work in subduing prey. Some paleontologists have proposed that Tarbosaurus might have hunted in family groups, though conclusive evidence for social hunting behaviors remains elusive.

Growth and Development

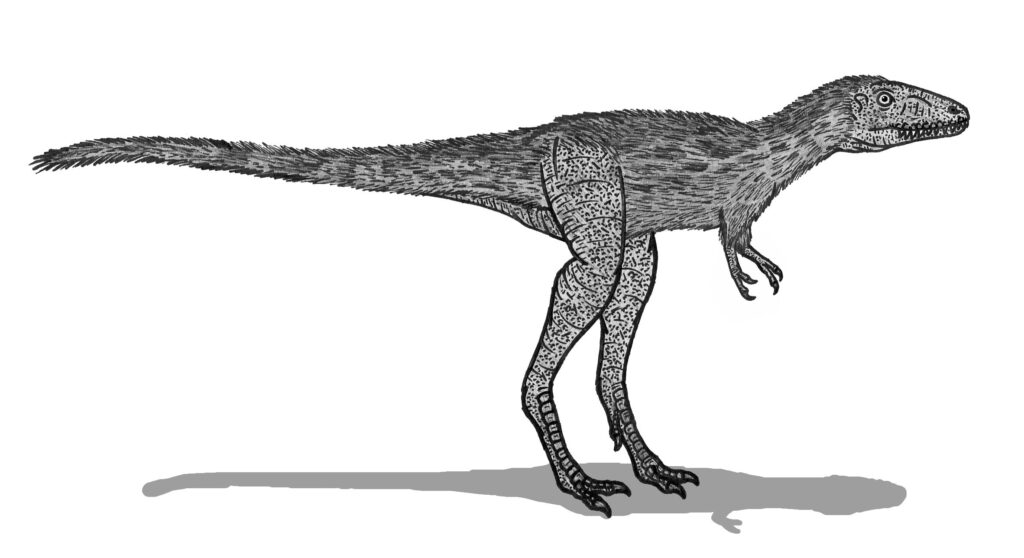

The growth pattern of Tarbosaurus has been illuminated through the study of specimens representing different life stages. Like other tyrannosaurs, Tarbosaurus experienced remarkably rapid growth during its juvenile and subadult years, potentially gaining over 200 kilograms (440 pounds) annually during peak growth phases. Histological studies of Tarbosaurus bones show growth rings similar to tree rings, indicating that these animals reached sexual maturity between 10 and 15 years of age, though they continued growing into their twenties. Juvenile Tarbosaurus specimens display proportionally longer legs, smaller heads, and more slender builds compared to the robust adults, suggesting different hunting strategies at different life stages. Young Tarbosaurus were likely more agile pursuers of smaller prey, while adults evolved into powerful ambush predators capable of tackling the largest herbivores. This dramatic transformation from relatively nimble juveniles to massive adults represents one of the most extreme ontogenetic (developmental) changes known among dinosaurs.

Brain and Sensory Capabilities

Advanced imaging techniques have allowed paleontologists to study endocasts of Tarbosaurus brains, revealing fascinating insights into its sensory capabilities. The brain of Tarbosaurus, while relatively small compared to its body size, featured well-developed olfactory bulbs, suggesting a highly acute sense of smell that would have been crucial for locating prey and carrion. The portions of the brain associated with vision were also substantial, indicating that Tarbosaurus likely had excellent eyesight, possibly with some degree of binocular vision for depth perception. The inner ear structure suggests Tarbosaurus had good hearing and a refined sense of balance. Interestingly, the areas of the brain associated with higher cognitive functions were relatively developed for a non-avian dinosaur, though not nearly as advanced as those of modern birds or mammals. These neurological adaptations collectively equipped Tarbosaurus with the sensory toolkit necessary to reign as the dominant predator in its ecosystem.

The Nemegt Ecosystem

The Nemegt Formation, where most Tarbosaurus fossils have been discovered, preserves one of the most complete Late Cretaceous ecosystems known from Asia. This rich paleoenvironment supported a diverse community of dinosaurs, with Tarbosaurus firmly established at the top of the food chain. Large herbivores sharing this habitat included the duck-billed hadrosaur Saurolophus, the long-necked sauropod Nemegtosaurus, and the heavily armored ankylosaur Tarchia, all potential prey for the mighty Tarbosaurus. The ecosystem also supported smaller predators like the dromaeosaurid Adasaurus and the enigmatic Therizinosaurus with its massive claws, though these would have likely avoided direct competition with Tarbosaurus. Crocodilians, turtles, mammals, and a variety of plants complete this complex ecosystem. The abundance of fossilized material from the Nemegt Formation has allowed paleontologists to reconstruct the paleoecology in remarkable detail, painting a picture of a vibrant, humid floodplain environment that supported one of the most diverse dinosaur communities of the Late Cretaceous period.

Comparison with Tyrannosaurus Rex

The striking similarities between Tarbosaurus and its North American cousin, Tyrannosaurus rex, have fascinated paleontologists for decades. Both were massive apex predators with enormous skulls, powerful jaws, and reduced forelimbs, clearly indicating their close evolutionary relationship. However, subtle anatomical differences tell the story of their divergent evolutionary paths. Tarbosaurus possessed a narrower skull with less binocular vision than T. rex, suggesting slightly different hunting strategies. Its arms were proportionally smaller, with only two functional fingers compared to T. rex’s three. Tarbosaurus also had more numerous teeth that were generally smaller and more laterally compressed than those of T. rex. These differences likely reflect adaptations to different prey types and environmental conditions. Despite these variations, the remarkable convergence in overall body plan between these two giant predators, separated by thousands of miles, demonstrates how similar ecological niches can produce comparable evolutionary outcomes even across different continents.

Fossil Discoveries and Notable Specimens

The catalog of Tarbosaurus discoveries includes several extraordinarily well-preserved specimens that have significantly advanced our understanding of this dinosaur. The holotype specimen, discovered during the Soviet-Mongolian expeditions of the 1940s, provided the first glimpse of this Asian tyrannosaur. Perhaps the most impressive discovery came in 1974 when paleontologists unearthed “Pin,” a nearly complete Tarbosaurus skeleton with approximately 80% of its bones intact, including a beautifully preserved skull. More recently, the “Fighting Dinosaurs” specimen, discovered in 1971, captures a Tarbosaurus locked in combat with a Protoceratops, providing rare behavioral evidence of predator-prey interaction frozen in time. Juvenile Tarbosaurus specimens have also been recovered, allowing scientists to study growth patterns. In 2012, a controversy erupted when a nearly complete Tarbosaurus skeleton was sold at auction in the United States, leading to a legal battle that ultimately resulted in the specimen’s return to Mongolia, highlighting the importance of protecting fossil resources from illegal trafficking.

Reproduction and Life History

The reproductive biology of Tarbosaurus, while not directly preserved in the fossil record, can be reconstructed through comparison with related tyrannosaurs and other theropod dinosaurs. Like other large theropods, Tarbosaurus likely laid elongated eggs in carefully constructed nests, possibly in low mounds of vegetation or shallow depressions in the ground. Based on evidence from related tyrannosaurs, clutch sizes probably ranged from 12-24 eggs. Parental care was likely present, with at least one parent guarding the nest against predators and potentially providing food for the hatchlings. Young Tarbosaurus probably grew rapidly, perhaps reaching half their adult size within 7-10 years. Sexual maturity likely occurred before full adult size was reached, perhaps around 15-18 years of age. The maximum lifespan of Tarbosaurus is estimated at 25-30 years, though few individuals likely survived to maximum age given the hazards of their environment, including combat injuries, disease, and seasonal food shortages.

Extinction and Legacy

Tarbosaurus disappeared from the fossil record approximately 66 million years ago, coinciding with the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event that wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs. This global catastrophe, triggered by a massive asteroid impact and exacerbated by extensive volcanic activity, radically transformed Earth’s ecosystems. As an apex predator dependent on large herbivorous dinosaurs for sustenance, Tarbosaurus would have been particularly vulnerable to ecosystem collapse. The extinction of Tarbosaurus and its contemporaries marked the end of the 80-million-year reign of non-avian dinosaurs and paved the way for the subsequent radiation of mammals. Despite its disappearance, Tarbosaurus has left an indelible legacy in our understanding of dinosaur evolution, particularly regarding the biogeography of Late Cretaceous ecosystems. The remarkable similarities between Tarbosaurus and Tyrannosaurus provide crucial evidence for understanding how dinosaur lineages evolved separately across different continents, making this Asian tyrannosaur far more than just a “T. rex cousin” but a significant evolutionary success story in its own right.

Cultural Impact and Scientific Importance

Tarbosaurus occupies a special place in both scientific research and popular culture, particularly in Mongolia and across Asia. As Mongolia’s most iconic dinosaur, Tarbosaurus features prominently in the country’s natural history museums and has become an important national symbol, even appearing on Mongolian currency and postage stamps. The scientific importance of Tarbosaurus extends far beyond regional pride, however, as it provides crucial evidence for understanding dinosaur evolution across continents. The similarities and differences between Tarbosaurus and its North American relatives offer valuable insights into how geography influences evolutionary pathways. Additionally, Tarbosaurus fossils have been central to ongoing legal and ethical discussions about fossil ownership, repatriation, and the protection of natural history resources. The 2012 case of a smuggled Tarbosaurus skeleton that was eventually returned to Mongolia helped establish important legal precedents for combating the illegal fossil trade and recognizing nations’ rights to their paleontological heritage.

Conclusion

Tarbosaurus bataar stands as one of the most impressive predators to have ever walked the Earth. This Asian tyrannosaur, with its massive skull, bone-crushing bite, and dominant presence in the Late Cretaceous ecosystems of Mongolia and China, continues to captivate paleontologists and dinosaur enthusiasts alike. Through decades of careful excavation, preparation, and study, we’ve pieced together a remarkably detailed portrait of this magnificent creature – from its growth patterns and sensory capabilities to its hunting strategies and evolutionary relationships. As research continues with new technologies and discoveries, our understanding of Tarbosaurus will undoubtedly deepen further. Yet even with what we know today, it’s clear that Tarbosaurus was far more than simply an Asian version of T. rex, but rather a uniquely adapted apex predator that evolved to dominate its specific environmental niche. Asia’s tyrannosaur king may have vanished 66 million years ago, but its scientific and cultural legacy continues to evolve, enriching our understanding of Earth’s incredible prehistoric past.