When most people picture the Triassic period, they picture dinosaurs. Small ones, sure, but still dinosaurs – scurrying around, slowly working their way up the food chain. It’s an image baked into documentaries, textbooks, and museum dioramas. Honestly, it’s also very wrong.

The real story of Triassic predation is far stranger, more dramatic, and in many ways more fascinating than the dinosaur tale you were handed in school. The creatures that actually ruled this world were a group of animals so overlooked that most people have never even heard their names. You might want to sit down for this one. Let’s dive in.

The World You Need to Imagine First

You have to understand the stage before you can appreciate the actors on it. The Triassic period was the first period of the Mesozoic era and occurred between roughly 252 million and 201 million years ago, following the great mass extinction at the end of the Permian period. That extinction was catastrophic beyond comprehension – the fossil record shows that as many as roughly nineteen in twenty of all species on the planet perished.

At the beginning of the Triassic, most of the continents were concentrated in the giant C-shaped supercontinent known as Pangaea, and the climate was generally very dry with very hot summers and cold winters in the continental interior. Life was rebuilding itself from near-zero. The Triassic period was an unusual time, situated between two of the Big Five mass extinctions, meaning that many “experimental” lineages arose and thrived during that time, only to go extinct soon after. The ecosystem was basically a blank canvas, and nature was about to paint something very unexpected.

Dinosaurs Were Not in Charge – Not Even Close

Here’s the thing that surprises almost everyone: dinosaurs existed during the Triassic, yes. A specialized group of archosaurs called dinosaurs first appeared in the Late Triassic but did not become dominant until the succeeding Jurassic Period. In other words, being around and being in charge are two very different things. In the Late Triassic Period, dinosaurs were not at the top of the food chain. Instead, early large reptiles called phytosaurs and rauisuchids dominated, while early meat-eating dinosaurs like Coelophysis relied on their speed and agility to catch a variety of animals like insects and small reptiles.

Most Triassic dinosaurs were small predators, and only a few were common, such as Coelophysis, which was only about one to two metres long. Think about that for a moment. The creatures you’ve been taught to associate with prehistoric dominance were, at this time, basically the underdogs – fast, scrappy, and living in the shadow of something far more terrifying. At the very beginnings of the dinosaur era, they were small and suppressed by their rival rauisuchians, which were the largest terrestrial carnivores during the Middle and Late Triassic and had cosmopolitan distribution.

Meet the Rauisuchians: The True Lords of the Land

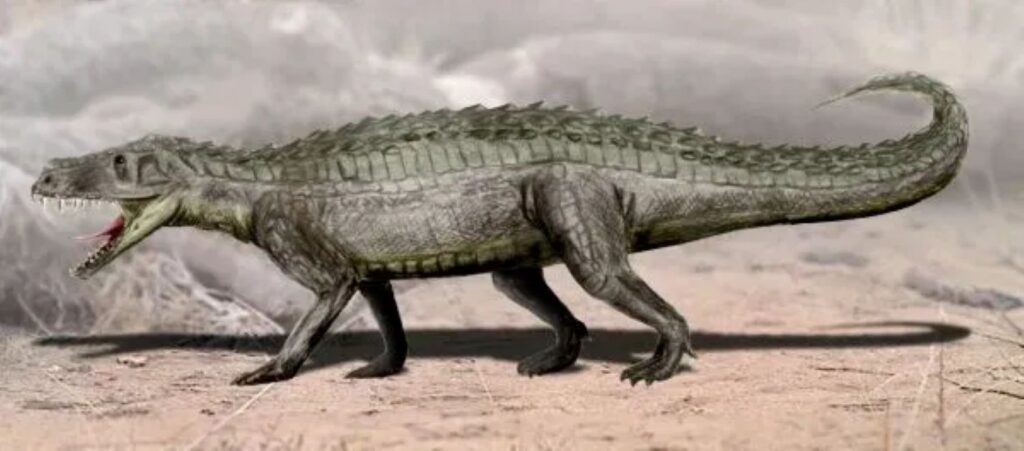

Rauisuchia is a grouping of carnivorous pseudosuchian archosaurs that flourished during the Middle to Late Triassic, serving as dominant apex predators in terrestrial ecosystems worldwide before the rise of dinosaurs. Honestly, “dominant” barely covers it. Rauisuchians were the keystone predators of most Triassic terrestrial ecosystems, and over twenty-five species have been found, including giant quadrupedal hunters, sleek bipedal omnivores, and lumbering beasts with deep sails on their backs. They probably occupied the large-predator niche later filled by theropods.

Their large size – five to eight or more metres long – and morphological similarities to post-Triassic theropod dinosaurs, including deep skulls and serrated dentitions, suggest these animals were apex predators. It’s a classic case of nature building the same tool twice. Middle and Late Triassic pseudosuchian archosaurs exhibit higher levels of morphological diversity than at any other point in their evolutionary history. This group was not a footnote in prehistory – they were the main event.

Postosuchus: The North American Terror

One of the most unusual and interesting rauisuchians discovered is Postosuchus, from the Triassic Dockum Formation of Texas, and Postosuchus and its contemporary animals were found near Post, in Garza County. Think of it as the T. rex of its time – not a dinosaur, but occupying exactly that kind of nightmarish ecological role. Postosuchus was the arch-predator in the Triassic forest of the American Southwest, about fifteen feet long and eight feet high, and its skull was very large and equipped with sharp, serrated teeth for cutting flesh.

Postosuchus was a large four-to-six metre long rauisuchian archosaur from the Late Triassic Period, with dagger-like teeth up to seven or eight centimetres long. You’d never want to be its neighbor. Postosuchus was probably an ambush predator that captured its prey by stealth and surprise, much like the modern Komodo dragon of Indonesia. Nature rarely gets more formidable than a crocodile-relative the size of a car, hiding in dense Triassic brush.

Fasolasuchus: The Biggest Land Predator You’ve Never Heard Of

If Postosuchus was terrifying, Fasolasuchus was something else entirely. Fasolasuchus is likely the largest known rauisuchian, with an estimated length of eight to ten metres. Let that sink in. With an estimated length of eight to ten metres, this would make Fasolasuchus the largest terrestrial predator to have ever existed save for large theropods, surpassing even its rauisuchian counterpart Saurosuchus at seven metres and many medium-sized theropods.

Fossils have been found in the Los Colorados Formation of northwestern Argentina, dating back to the Norian stage of the Late Triassic, making it one of the last rauisuchians to have existed before the group became extinct at the end of the Triassic. I find it genuinely mind-blowing that a predator of this scale barely registers in popular culture. Rauisuchians continued to be the world’s top terrestrial predators until they were replaced by theropod dinosaurs at the end of the Triassic and in the Early Jurassic. They didn’t fade – they were wiped out by catastrophe.

Phytosaurs: The Ambush Artists of the Water’s Edge

Phytosaurs were a particularly common group which prospered during the Late Triassic – long-snouted and semiaquatic predators that resemble living crocodiles and probably had a similar lifestyle, hunting for fish and small reptiles around the water’s edge. But recent evidence shows they were far more dangerous than that simple description suggests. About two hundred and ten million years ago, when the supercontinent of Pangea was starting to break up, phytosaurs and rauisuchids were both apex predators at the top of the food chain.

At twelve metres long, the largest phytosaurs were as large or larger than the biggest living crocs, and they were the largest predators of the Triassic Period outside of the ocean-going ichthyosaurs. Twelve metres. That’s roughly the length of a standard school bus. Phytosaur skeletons have been found with the remains of other reptiles in their stomachs, including terrestrial animals like rhynchosaurs, and phytosaurs may have ambushed land animals when they came to rivers or water holes to drink, just as living crocodilians attack antelopes and deer. The boundary between water and land meant almost nothing to them.

When Predators Ate Each Other: The Chinle Ecosystem Mystery

Here is where things get genuinely strange. The Late Triassic Chinle Formation of North America preserves something that puzzled paleontologists for years. These fossil marks provide an opportunity to start exploring the seemingly unbalanced terrestrial ecosystems from the Late Triassic of North America, in which large carnivores far outnumbered herbivores in terms of both abundance and diversity. Usually, prey animals outnumber their predators by a wide margin – that’s just how food chains work.

This kind of “intraguild predation” happened between carnivores of two different trophic levels in the environment, and the Chinle ecosystem was filled with larger carnivores and very few big herbivores. So what were all these enormous predators eating? It is possible that intraguild predation was higher due to the huge concentration of carnivorous animals – the carnivores were thus feeding on one another, getting past the niche partitioning that would normally allow such animals to coexist. It’s a chilling picture: a world where the top predators hunted each other simply to survive.

The Ocean Had Its Own Nightmare: Triassic Ichthyosaurs

While rauisuchians and phytosaurs ruled the land, the Triassic oceans had their own story of unexpected dominance. Ichthyosaurs radiated in the latest Early to Middle Triassic and became air-breathing top predators during the process of reconstruction of the Triassic marine ecosystem after the end-Permian extinction. They evolved with breathtaking speed to fill a world of empty ecological niches. Fossils likely represent the oldest evidence for predation on megafauna – animals equal to or larger than humans – by marine tetrapods, specifically a thalattosaur of roughly four metres in total length found in the stomach of a Middle Triassic ichthyosaur of about five metres.

Big ichthyosaurs, like the large Triassic-period Thalattoarchon, boasted dangerous teeth that were likely used for catching prey the animals’ own size. These were not gentle filter-feeders drifting through warm seas. They were aggressive, fast, and capable of swallowing prey whole in the open ocean. Megafaunal predation probably started nearly simultaneously in multiple lineages of marine reptiles around two hundred and forty-two to two hundred and forty-three million years ago. The Triassic oceans were, in every sense, a war zone.

The Mass Extinction That Changed Everything

So why don’t most people know any of this? Because the story ended with brutal finality. The end of the Triassic period was marked by a major mass extinction – the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event – that wiped out many groups, including most pseudosuchians, and allowed dinosaurs to assume dominance in the Jurassic. It was catastrophic. The dominant predators of the Triassic were essentially erased from the equation overnight, in geological terms.

At the end of the Triassic there was a drastic change in the global climate, and many of the Triassic forests gave rise to more open prairie with a shift to more dry and arid habitats, reflected by the occurrence of dune sands over a large area of the southwestern United States. The world the rauisuchians had mastered simply ceased to exist. In this open country, the great speed and endurance of dinosaurs became more advantageous, and the ambush hunting strategy of Postosuchus and other rauisuchians became less effective, leading them to decline and go extinct at the end of the Triassic while the dinosaurs proliferated. It was not a defeat in battle – it was a world that moved on without them.

Conclusion: History Belongs to the Survivors, Not the Rulers

The Triassic period is a humbling reminder that dominance is never permanent. The rauisuchians, phytosaurs, and giant ichthyosaurs were the true apex predators of their world – bigger, more established, and more ecologically entrenched than any Triassic dinosaur. Yet almost none of them survived to see the Jurassic sunrise. While early dinosaurs remained minor players compared to other reptilian groups, their agility, upright stance, and efficient breathing gave them advantages that would prove crucial in the long run.

History, it seems, doesn’t reward the strongest. It rewards the most adaptable. The creatures that briefly inherited a post-extinction world built something extraordinary, only to be replaced by what had been living quietly in the margins the entire time. Next time you look at a crocodile resting on a riverbank, remember: its ancient relatives were once the undisputed rulers of Earth’s most violent era. What do you think – does that change the way you see prehistoric life? Tell us in the comments.