Picture yourself wandering through an English quarry in the late 1600s, stumbling upon a bone the size of a baseball bat, thick as your forearm. You’d have no idea you were holding the key to unlocking Earth’s most magnificent creatures. This moment sparked a scientific revolution that would reshape our understanding of prehistoric life forever.

The story begins centuries before anyone knew what dinosaurs were. It’s a tale of mistaken identities, brilliant deductions, and the gradual dawning of an incredible truth. Most remarkably, it all started in one small English village where workers split stones for roofing tiles, accidentally uncovering giants that had been sleeping for millions of years.

The Mysterious Giant Bone of 1676

In 1676, the lower part of a massive femur was discovered in the Taynton Limestone Formation of Stonesfield limestone quarry, Oxfordshire. The bone was given to Robert Plot, Professor of Chemistry at the University of Oxford and first curator of the Ashmolean Museum. Plot stared at this colossal fragment, roughly two feet long and wider than a human hand.

He thought it must be a thigh bone from a war elephant, from some ancient battle. Or the femoral head of a giant human, as described in the Bible. Plot published a description of it in 1677 in the Natural History of Oxfordshire. The illustration that accompanied the description is the first known published illustration of a dinosaur bone. Little did Plot realize he was documenting humanity’s first scientific encounter with a dinosaur fossil.

The Stonesfield Slate Quarry: A Prehistoric Treasure Trove

The quarry area in the small town of Stonesfield, Oxfordshire, England, has been called the “best Middle Jurassic terrestrial reptile site in the world.” Curiously, the so-called Stonesfield slate isn’t slate, which makes sense considering the source rock is so fossiliferous. It is, in fact, limestone, deposited in a shallow marine environment.

The limestone formed roughly 165 million years ago during the Middle Jurassic period, when this area was a shallow sea dotted with lagoons. The bones most likely washed into the water followed by rapid burial by sand transported offshore during storm events. Other fossils found in the quarries include fish, reptiles, mammals, ammonites, bivalves, gastropods, insects, and 13 species of terrestrial plants.

Workers split the stone using an ingenious method that relied on winter frost. They would pull the limestone out of the ground (20 to 70 feet deep) in a rough block called a “pendle” and let it sit in a field and absorb water. To ensure moisture retention, the quarrymen would pile dirt atop the blocks and/or douse the stone in water. Over several cold winters, water would penetrate the bedding planes and split the stone into usable pieces.

William Buckland: The Eccentric Genius Who Identified the First Dinosaur

It was acquired by William Buckland (1784–1856), Reader in Geology at the University of Oxford, after being found in a slate quarry in Stonesfield, Oxfordshire. Buckland was no ordinary professor. One of my all-time favorite geologists, Buckland was an ordained priest in the Church of England; notorious for eating practically everything; one of earliest professional geology instructors, at Oxford University; a fellow of the Royal Society; and the first to recognize the importance of coprolites (he coined the term).

The bones were apparently acquired by William Buckland, Professor of Geology at the University of Oxford and fellow of Corpus Christi. Suspecting he’d come across something special, Buckland showed this and other Stonesfield bones to comparative anatomist Georges Cuvier, who noted similarities with living lizards. This iconic fossil was used in the first scientific description of a dinosaur – Megalosaurus – in 1824. The name Buckland chose, Megalosaurus, means ‘great lizard’.

The Historic 1824 Scientific Description

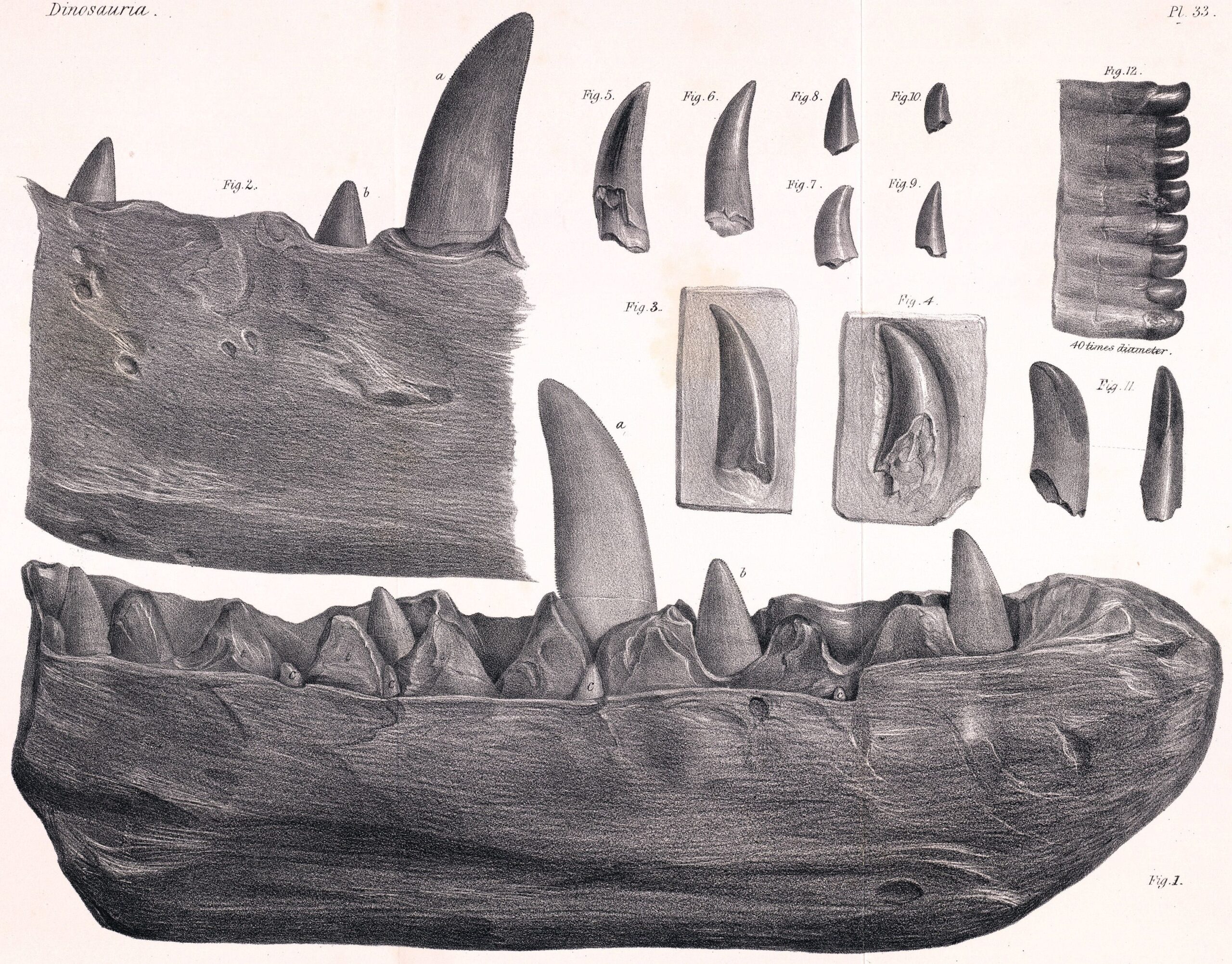

In 1824, William Buckland gave the genus the name Megalosaurus in his article “Notice on the Megalosaurus or Great Fossil Lizard of Stonesfield,” describing it as an extinct giant reptile. Among these early efforts, in 1824, University of Oxford geologist William Buckland dubbed the collection of skeletal pieces from Stonesfield Megalosaurus, the first dinosaur to receive a scientific name. Working through the science of comparative anatomy, Buckland was sure that Megalosaurus was a giant reptile.

The publication was groundbreaking, though Buckland’s interpretation reflected the scientific understanding of his time. Even though the leg bones indicated an animal with upright, column-like legs, like most mammals, the details of the teeth were clearly reptilian. He envisioned the animal as crocodile-like in nature. “The megalosaurus itself was probably an amphibious animal,” he wrote in his paper.

The lithograph of the Megalosaurus jaw that accompanied the description was based on drawings done by Buckland’s wife, Mary Morland. These detailed illustrations became some of the most important scientific images in paleontological history.

Richard Owen Coins “Dinosaur” in 1842

It was only later, in 1842, that Richard Owen coined the term ‘dinosaur’ to describe a group of animals including Megalosaurus and other recently found ‘great lizards’ such as Iguanodon. In 1842, the anatomist Richard Owen attempted to bring order to the recent discoveries of prehistoric reptiles. In what we today would call a “review article,” Owen discussed in considerable detail all of the bones and teeth found by Gideon Mantell, William Buckland, and many others, and he tried valiantly to sort them out in good Linnaean fashion. He found that three of the vanished genera–Iguanodon, Megalosaurus, and Hylaeosaurus– shared similarities in the structure of their vertebrae, and in their sturdy, elephant-like posture.

So Owen grouped them as a sub-order in the Saurian order, and he called them: Dinosauria, the “terrible lizards”. The term “dinosaur” was born. The term is derived from Ancient Greek δεινός (deinos) ‘terrible, potent or fearfully great’ and σαῦρος (sauros) ‘lizard or reptile’. Though the taxonomic name has often been interpreted as a reference to dinosaurs’ teeth, claws, and other fearsome characteristics, Owen intended it also to evoke their size and majesty.

The First Mesozoic Mammal Discovery

Stonesfield Slate Quarry holds another extraordinary distinction beyond dinosaurs. The first mammal fossil was discovered from Stonesfield Slate Mines in approximately 1764, although the significance of the material was not fully appreciated until subsequent study by Buckland some 50 years later. The Stonesfield Slate Mines site is significant as a historical site, the location of the first reported Mesozoic mammal remains and the first site to yield tritylodont fossils.

Found in the Stonesfield Slate, it was one of the first Mesozoic mammals ever found and described, although like the other mammal jaws found at the same time, it was mistakenly thought at first to be a marsupial. Phascolotherium was one of the first mammals described from Mesozoic-aged rocks. Buckland showed the fossil jaws of Stonesfield to the exceptional comparative anatomist, Georges Cuvier, who incorrectly identified them as marsupials, based on the similarity of the bones to modern marsupials.

From Mr. W. J. Broderip we learn that these rare fossils were obtained as follows : – “An ancient stonemason living at Heddington … made his appearance in my rooms at Oxford with two specimens of the lower jaws of mammiferous animals, embedded in Stonesfield slate… . The fossil purchased by Broderip himself is the type specimen of Phascolotherium; Buckland’s fossil is the type specimen with which we are now concerned.

The Revolutionary Impact on Science and History

The Stonesfield discoveries fundamentally transformed humanity’s understanding of Earth’s history. One hundred and fifty years later, in 1824, Oxford University’s first geologist studied more fossils that had been found in English canals and quarries and concluded they came from an extinct giant reptile species. This revelation shattered prevailing beliefs about the age and nature of our planet.

In April 1842, 175 years ago this year, the dinosaurs were created – in a taxonomic sense at least. In a landmark paper in the Report for the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Richard Owen, one of the world’s best comparative anatomists, introduced the term ‘Dinosauria’ for the very first time. Owen coined the term using a combination of the Greek words Deinos, meaning ‘fearfully great’, and Sauros, meaning ‘lizard’, in order to describe a new and distinct group of giant terrestrial reptiles discovered in the fossil record.

The discoveries proved that massive creatures once dominated Earth, challenging religious and scientific orthodoxy. To this day, however, no one has ever found anything near a complete skeleton of Megalosaurus. The task of reconstructing the form of such a dinosaur is like trying to put together a puzzle when you have a pile of pieces from different sets, but no box. Yet from these fragments, scientists began piecing together an entirely new chapter of natural history.

These first fossil finds from Stonesfield Slate Quarry ignited a passion for paleontology that continues today. Scientists now know that Megalosaurus bucklandii was a Jurassic theropod dinosaur – a carnivore that walked on its hind legs and was about 20 ft (6 m) long. The only specimens of this particular dinosaur come from the Bathonian Age (166 million years ago) of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, England. From Plot’s mysterious giant bone to Owen’s scientific revolution, these discoveries opened our eyes to the incredible diversity of ancient life.

Conclusion

The humble Stonesfield Slate Quarry became the birthplace of paleontology as we know it. What started as a puzzling oversized bone fragment in 1676 evolved into the foundation of our modern understanding of prehistoric life. These discoveries didn’t just introduce us to dinosaurs, they revolutionized our comprehension of Earth’s deep history and the incredible creatures that once called it home.

The journey from Robert Plot’s mysterious “giant human femur” to Richard Owen’s scientific taxonomy of dinosaurs demonstrates how persistent curiosity and rigorous study can unlock nature’s greatest secrets. Today, as we continue discovering new dinosaur species worldwide, we owe a debt to that small English quarry where workers splitting slate accidentally split open the door to the Age of Dinosaurs.

What strikes me most about this story is how close we came to missing these discoveries entirely. What do you think might still be waiting beneath our feet, just waiting for the right moment to rewrite history again?