Long before humans understood what dinosaurs were, our ancestors were finding their fossilized remains and creating narratives to explain them. These massive bones and strange teeth inspired myths of dragons, giants, and monsters across cultures worldwide. However, it wasn’t until relatively recently in human history that we began to develop the scientific framework to accurately interpret these ancient relics. The discovery and scientific interpretation of the first dinosaur fossils marked a pivotal moment in our intellectual development, initiating a profound shift in how we understand Earth’s history and our place within it. This transformation didn’t just change science—it changed storytelling itself, creating a new genre of narrative that blended rigorous evidence with imaginative reconstruction. Let’s explore how the first dinosaur discoveries sparked a revolution in scientific thinking and public imagination that continues to evolve today.

The Prehistory of Paleontology: Fossils Before Science

Before the scientific revolution, fossils were frequently misinterpreted through the lens of local mythology and biblical narratives. In ancient China, dinosaur bones were thought to be the remains of dragons and were carefully documented in medicinal texts as “dragon bones.” Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder described fossilized shark teeth as “tongue stones” that fell from the sky during lunar eclipses. Throughout medieval Europe, massive dinosaur bones were often displayed in churches and town halls as evidence of biblical giants or the victims of Noah’s flood. These interpretations weren’t merely superstitious—they represented sincere attempts to incorporate physical evidence into existing worldviews. The cognitive framework necessary to understand fossils as prehistoric animals simply didn’t exist yet, demonstrating how profoundly our cultural context shapes our interpretation of physical evidence. These early misidentifications remind us that seeing isn’t just about the eye, but about the mind that interprets what the eye perceives.

The Birth of Systematic Fossil Study

The groundwork for dinosaur paleontology was laid during the scientific revolution of the 17th and 18th centuries, as naturalists began developing more systematic approaches to studying the natural world. Danish scientist Nicolas Steno established the foundational principles of stratigraphy in 1669, demonstrating that rock layers form chronologically with the oldest at the bottom. His contemporary Robert Hooke proposed that fossils were the remains of extinct creatures rather than “sports of nature” or failed creations. By the late 18th century, Georges Cuvier in France had established comparative anatomy as a discipline, demonstrating that fossils could be reconstructed by comparing them with living animals. These methodological advances were revolutionary, creating the intellectual framework necessary for interpreting fossil evidence scientifically. Crucially, this period also saw the emergence of a community of scholars who communicated through letters and published works, establishing the social infrastructure that would eventually allow dinosaur discoveries to be shared, debated, and incorporated into a cohesive scientific narrative.

Mary Anning: The Mother of Paleontology

Though not specifically a dinosaur discoverer, Mary Anning deserves prominent mention in any discussion of early fossil science. Born to a poor family in Lyme Regis, England, Anning became one of history’s most skilled fossil hunters despite having no formal scientific education. Beginning in the 1810s, she discovered the first complete ichthyosaur skeleton, the first complete plesiosaur, and numerous other marine reptiles along the Jurassic Coast. Despite her groundbreaking discoveries, Anning struggled for recognition in the male-dominated scientific community of 19th-century Britain. Gentlemen scientists often purchased her specimens and published papers about them without crediting her work. Nevertheless, Anning’s meticulous methods and observational skills established standards for fossil collection that influenced all subsequent paleontology. Her life demonstrates both the democratic nature of fossil discovery—requiring keen eyes and persistence more than formal credentials—and the social barriers that have shaped who gets credit in the history of science.

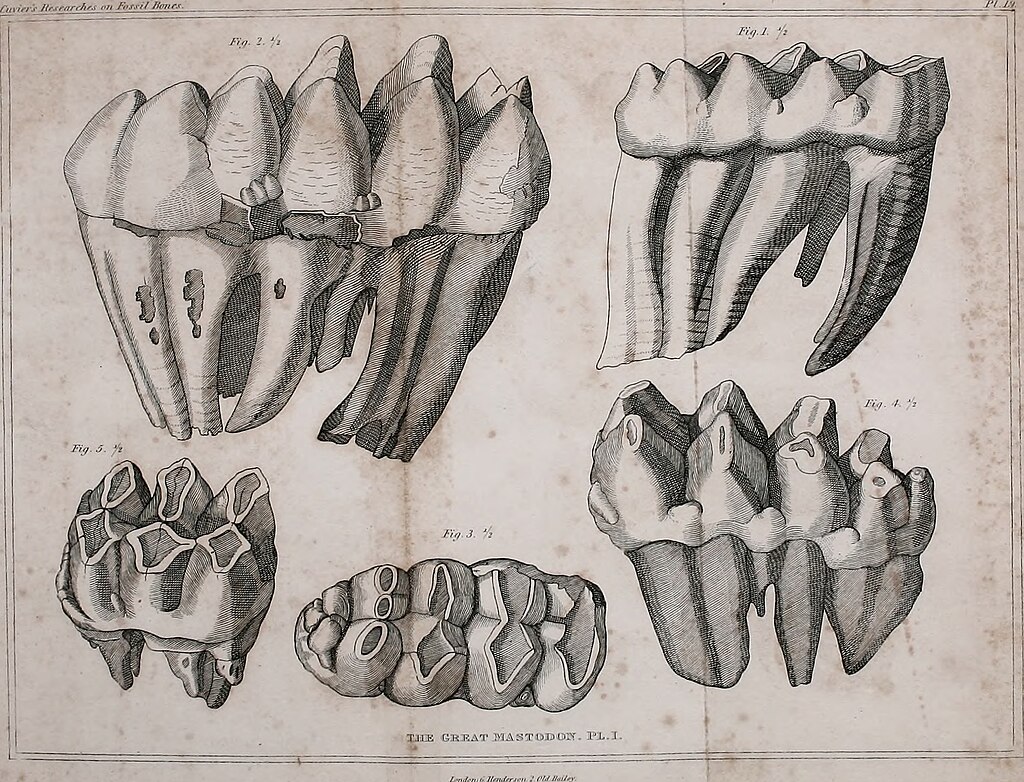

Gideon Mantell and the Iguanodon Mystery

The scientific recognition of dinosaurs began in earnest with Gideon Mantell, a country doctor with a passion for geology. In 1822, his wife Mary Ann noticed unusual fossilized teeth while accompanying him on a house call near Sussex, England. After years of research and comparison with modern reptiles, Mantell determined they belonged to a massive extinct herbivorous reptile. He named it Iguanodon, meaning “iguana tooth,” based on similarities to modern iguana teeth, though much larger. Mantell’s discovery was revolutionary because it clearly represented a giant land-dwelling reptile unlike any known to exist in the modern world. Initially met with skepticism by the scientific establishment, Mantell persisted in collecting more fossils and evidence. His 1825 paper on Iguanodon became a cornerstone of early dinosaur science, despite initial resistance from established figures like Georges Cuvier. Mantell’s work demonstrates how scientific breakthroughs often come from passionate amateurs working at the periphery of established institutions, driven more by curiosity than career advancement.

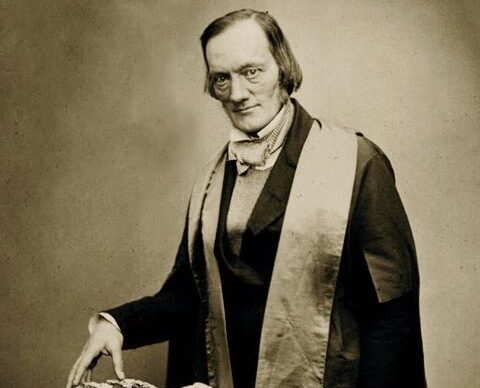

Sir Richard Owen and the Coining of “Dinosauria”

While Mantell and others had discovered individual dinosaur species, it was anatomist Richard Owen who recognized these creatures represented a distinct group of reptiles. In 1842, after studying the fossils of Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus, Owen coined the term “Dinosauria,” meaning “terrible lizards,” to describe these extinct giants. Owen was a brilliant anatomist but a controversial figure who often clashed with contemporaries and sometimes took credit for others’ discoveries. His conception of dinosaurs differed significantly from our modern understanding—he envisioned them as massive, mammal-like reptiles rather than the diverse group we recognize today. Nevertheless, Owen’s taxonomic work gave these creatures a collective identity in scientific literature and public imagination. He also played a crucial role in bringing dinosaurs to the public through his collaboration with sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins on the Crystal Palace dinosaur models, unveiled in 1854. These life-sized reconstructions, though inaccurate by modern standards, were the first attempt to visualize dinosaurs for the public and sparked tremendous popular interest.

The Bone Wars: Competition Fuels Discovery

The most dramatic chapter in early dinosaur paleontology unfolded in post-Civil War America with the infamous “Bone Wars” between Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh. What began as a professional rivalry escalated into a bitter feud as both men raced to discover and name new dinosaur species across the American West. Their teams dynamited fossil sites after excavation to prevent rivals from finding more specimens, bribed railroad workers for information about new discoveries, and published hasty descriptions to claim priority. Despite these unethical tactics, the Cope-Marsh rivalry dramatically accelerated dinosaur discovery, with over 142 new species identified between them. The Bone Wars yielded iconic dinosaurs like Allosaurus, Diplodocus, Stegosaurus, and Triceratops, transforming public and scientific understanding of prehistoric life. This period demonstrates how human ambition, ego, and competition can simultaneously advance and corrupt scientific progress. It also established America as a center for dinosaur paleontology, shifting the focus from European museums to the fossil-rich American West.

Bringing Dinosaurs to Life: Early Artistic Reconstructions

As scientists assembled dinosaur skeletons, a parallel challenge emerged: how to translate these bone puzzles into convincing depictions of living creatures. Early artistic reconstructions reveal as much about Victorian cultural assumptions as about dinosaur anatomy. Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’ Crystal Palace dinosaurs depicted Iguanodon as a mammal-like quadruped with a horn on its nose (which was actually a thumb spike). Charles R. Knight’s paintings from the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought more scientific accuracy but still portrayed dinosaurs as slow, lumbering creatures, reflecting the prevailing scientific view. These reconstructions weren’t merely illustrations of scientific knowledge—they actively shaped both scientific and public perception of how dinosaurs looked and behaved. The most influential early popularizer was Knight, whose dramatic murals for the American Museum of Natural History established the dominant visual vocabulary for dinosaurs that persisted for decades. His work demonstrates how artistic interpretation inevitably fills the gaps in fossil evidence, making paleoart a unique fusion of scientific data and creative inference that continues to evolve with new discoveries.

From Cold-Blooded Failures to Dynamic Predators

Perhaps the most dramatic shift in dinosaur science occurred in the 1960s through 1980s with what became known as the “Dinosaur Renaissance.” Before this period, dinosaurs were generally portrayed as evolutionary dead-ends—cold-blooded, slow-moving, and dim-witted creatures that deservedly went extinct. This view began to change when paleontologist John Ostrom discovered Deinonychus in 1964, a swift predator with features suggesting high activity levels and possibly warm-blooded metabolism. Ostrom’s student, Robert Bakker, further developed these ideas in his provocative 1986 book “The Dinosaur Heresies,” arguing that dinosaurs were active, warm-blooded, and behaviorally complex animals. This revolution in thinking transformed dinosaurs from evolutionary failures into the dominant terrestrial vertebrates of their era—successful creatures whose descendants still thrive today as birds. The Dinosaur Renaissance didn’t just change scientific understanding; it dramatically altered cultural depictions of dinosaurs, as evidenced by the agile, intelligent Velociraptors of “Jurassic Park.” This period demonstrates how scientific narratives about nature are constantly evolving, shaped by new evidence and changing cultural contexts.

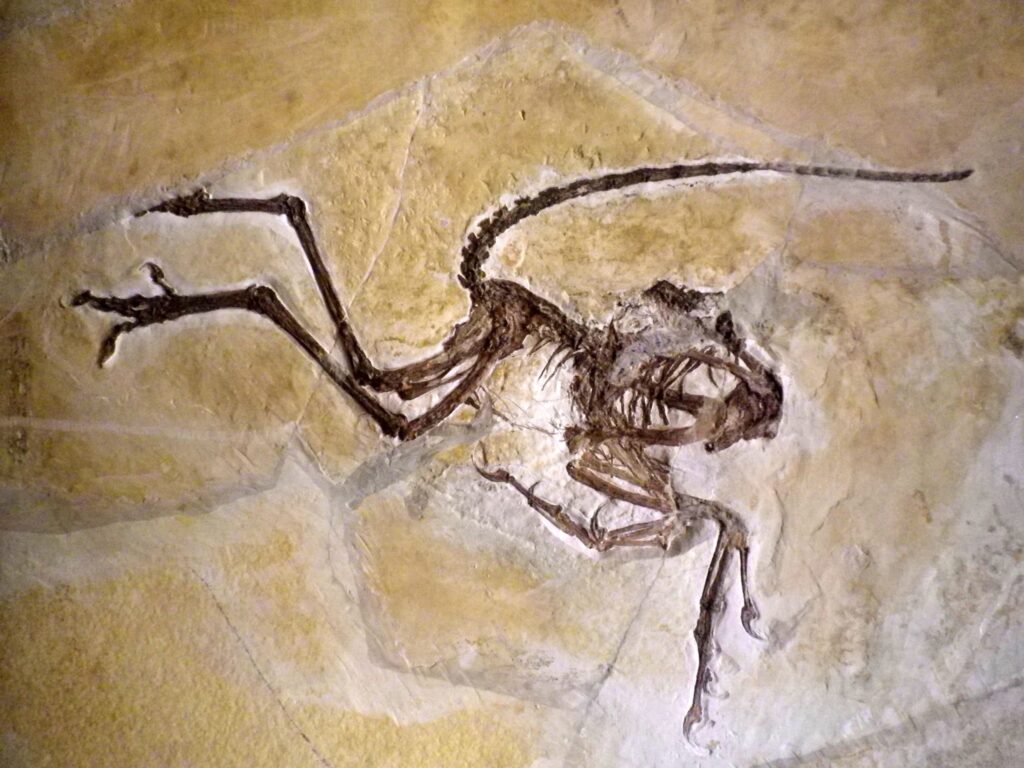

Dinosaurs and the Development of Evolutionary Theory

Dinosaur fossils played a crucial role in the development and acceptance of evolutionary theory. When Charles Darwin published “On the Origin of Species” in 1859, the fossil record was still relatively sparse, leading to criticism that the “missing links” between species undermined his theory. The discovery of Archaeopteryx in 1861—just two years after Darwin’s publication—provided dramatic evidence for evolution, showing a creature with both reptilian features (teeth, bony tail) and avian characteristics (feathers, wishbone). Though not recognized as a dinosaur at the time, Archaeopteryx is now understood as a transitional form between dinosaurs and birds. As the dinosaur fossil record expanded through the late 19th century, it provided compelling evidence for the gradual transformation of species over time. Today, the evolutionary relationship between dinosaurs and birds is one of the most well-documented examples of macroevolution, supported by hundreds of specimens showing the progressive acquisition of avian characteristics in theropod dinosaurs. This evidence demonstrates how fossil discoveries have been crucial in shaping our understanding of life’s history on Earth.

Museums and the Public Imagination

Natural history museums have been essential in translating dinosaur science into compelling public narratives. The first complete dinosaur skeleton mounted for public display was a Hadrosaurus assembled by Joseph Leidy at Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences in 1868, drawing record crowds fascinated by this glimpse into Earth’s past. By the early 20th century, philanthropists like Andrew Carnegie were funding expeditions to discover spectacular specimens for their namesake institutions, making dinosaur displays central to museum identity. These exhibits did more than present scientific information—they created narrative experiences that placed visitors within the sweep of deep time. The dramatic central halls of institutions like the American Museum of Natural History, with their towering Tyrannosaurus and Barosaurus specimens, became cathedral-like spaces celebrating evolutionary science. Museums thus became crucial mediators between scientific discovery and public understanding, translating technical papers into three-dimensional stories accessible to all ages and educational backgrounds. Even as scientific understanding has evolved, this public fascination with the tangible remains of prehistoric giants has remained constant.

Dinosaurs in Popular Culture

From Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 novel “The Lost World” to the blockbuster “Jurassic Park” franchise, dinosaurs have inspired countless fictional narratives that blend scientific fact with speculative storytelling. These popular depictions have profoundly influenced public perception of prehistoric life, sometimes spreading misconceptions but also sparking genuine interest in paleontology. The 1925 film adaptation of “The Lost World” featured groundbreaking stop-motion animation by Willis O’Brien, establishing dinosaurs as cinema stars decades before CGI. Ray Harryhausen continued this tradition with films like “One Million Years B.C.” (1966), though these productions often sacrificed scientific accuracy for dramatic effect by placing humans alongside dinosaurs. Michael Crichton’s “Jurassic Park” (1990) and Steven Spielberg’s 1993 film adaptation marked a turning point, incorporating contemporary scientific theories about active, intelligent dinosaurs while still employing creative license. This cultural fascination reveals how dinosaurs occupy a unique space in our collective imagination—scientifically documented yet distant enough in time to serve as projection screens for our fears and fantasies about nature’s power and the limitations of human control.

Modern Paleontology: New Technologies and Discoveries

Today’s paleontologists employ technologies that would seem like science fiction to the field’s pioneers. CT scanning allows researchers to examine fossils without damaging them, revealing internal structures and even brain cases that help determine sensory capabilities and intelligence. Scanning electron microscopy can identify microscopic structures in fossils, including the melanosomes that indicate the original colors of dinosaur feathers. Ancient DNA analysis, though not yet possible for dinosaurs themselves due to DNA degradation over millions of years, has revolutionized our understanding of more recent extinct species and the evolutionary relationships among living organisms. Perhaps most revolutionary has been the application of computational methods, from cladistics to determine evolutionary relationships to biomechanical modeling that can test hypotheses about how dinosaurs moved and functioned. These technologies have transformed paleontology from a primarily descriptive science to one that can test sophisticated hypotheses about ancient life. The fossil discoveries continue as well, with new dinosaur species being named at the rate of approximately one every two weeks, often from previously unexplored regions in China, Argentina, and Africa.

The Legacy of Scientific Storytelling

The journey from mysterious bones to scientifically reconstructed prehistoric ecosystems represents one of humanity’s greatest intellectual achievements. The development of dinosaur paleontology wasn’t merely a accumulation of fossils but the creation of a new kind of narrative—one that used physical evidence to reconstruct worlds no human had ever witnessed. This scientific storytelling required both rigorous methodology and disciplined imagination, combining the factual precision of science with the narrative power of art. Today’s paleoartists and science communicators stand in a tradition that began with those early Victorian reconstructions, continuing to translate technical findings into compelling stories that capture public imagination. The evolution of dinosaur science demonstrates how scientific understanding isn’t a simple march toward truth but a complex dialogue between evidence, interpretation, and cultural context. As new methods and discoveries continue to refine our understanding of these ancient creatures, the fundamental achievement remains: humans have learned to read the story of life’s past from fragments preserved in stone, extending our collective memory millions of years beyond human experience.

Conclusion

From misidentified “dragon bones” to precisely reconstructed ecosystems, the study of dinosaur fossils represents a profound evolution in how humans understand and narrate the natural world. The first dinosaur discoveries didn’t just add new creatures to our catalog of nature—they fundamentally altered our perception of Earth’s history and humanity’s place within it. They revealed a world before humans, populated by magnificent creatures that thrived for millions of years before disappearing, challenging religious narratives and inspiring new scientific methods. As we continue to unearth new fossils and develop new technologies to analyze them, the story of dinosaurs continues to evolve, reminding us that science itself is not a static body of facts but a dynamic process of discovery and interpretation. The enduring fascination with dinosaurs across cultures and generations speaks to their power as scientific evidence and as symbols that connect us to the vast, humbling timescale of our planet’s history.