When you think about great ancient civilizations, chances are your mind wanders to Egypt, Rome, or perhaps the Aztecs and Maya of Mesoamerica. Yet the landscape north of Mexico holds secrets that would stun most visitors who travel through the American heartland today. Long before European contact, complex societies thrived across , constructing massive earthworks, establishing extensive trade networks, and creating architectural marvels that rivaled those found anywhere else on the planet.

Most of these accomplishments have been overlooked or misunderstood for centuries. Some earthworks were plowed under by farmers who had no idea what lay beneath their fields. Others were dismissed by early settlers who refused to believe that Indigenous peoples could have built such sophisticated structures. Now, as archaeology advances and ancient voices begin to speak through the evidence left behind, a richer story emerges. What you are about to discover might just change how you view the deep history of this continent.

Cahokia: North America’s Lost Metropolis

Around the year 1100, a city covering roughly six square miles rose near the confluence of the Mississippi, Missouri, and Illinois Rivers, housing between 15,000 and 20,000 people. Let’s be real, that population figure was comparable to London and Paris at the same time. Cahokia’s population was larger than New York City or Philadelphia would be until the late 1700s.

The urban center contained about 120 earthworks of varying sizes, shapes, and functions, including 120 earthen pyramids. The main pyramid, Monks Mound, covered fifteen acres and rose in three major terraces to a height of one hundred feet, making it the third largest in the Americas. Monks Mound was over 100 feet high and covered 16 acres at its base. Walking around the reconstructed plaza today, you can barely grasp the scale of human effort this required. The inhabitants left no written records beyond symbols on pottery, marine shell, copper, wood, and stone.

In its heyday in the 1100s, Cahokia was the center for Mississippian culture and home to tens of thousands of Native Americans who farmed, fished, traded and built giant ritual mounds. Materials excavated at the site indicate that the city traded with peoples from as far away as the Gulf of Mexico, the Appalachians, the Great Lakes, and the Rocky Mountains. It’s hard to say for sure, but the civilization’s sudden rise and equally mysterious decline continues to puzzle scholars. Climate change in the form of back-to-back floods and droughts played a key role in the 13th century exodus.

The Ancestral Puebloans and Their Cliff Cities

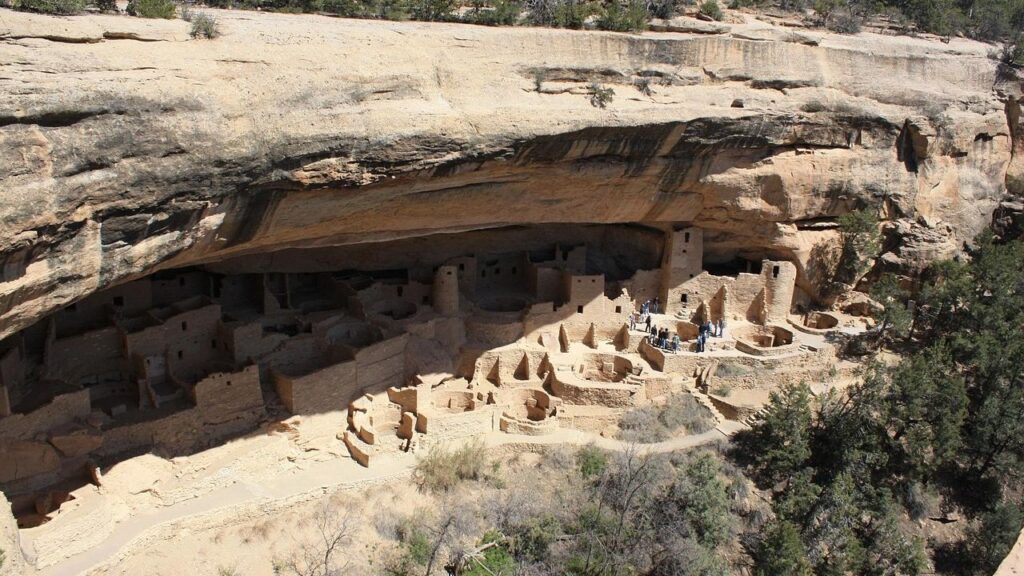

Picture yourself standing at the base of a towering sandstone cliff in what is now southwestern Colorado. High above, tucked into natural alcoves in the rock face, entire villages cling to the walls. Cliff Palace is the largest cliff dwelling in North America, built by the Ancestral Puebloans in Mesa Verde National Park.

Cliff dwellings were used during the Pueblo III period from roughly 1150 to 1300 in the Four Corners area, where Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah meet. During the 13th century, pueblo people constructed entire villages in the sides of cliffs. Honestly, the engineering challenges alone would have been staggering. The Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde had about 150 rooms and nearly two dozen kivas, which were circular ceremonial chambers.

The shift to cliff dwellings around 1150 may have been a defense against invading groups of ancestral Navajo and Apache. The ground-floor rooms lacked doors and windows, so houses could be entered only by climbing a ladder to the higher floor, and if the town were attacked, the ladders could be pulled up. These structures offered both protection and thermal efficiency. Most cliff dwellings face south, which would be advantageous during different seasons as the sun would be higher up in summer and not penetrate the overhangs, providing a cool place, while in winter the lower sun would warm the dwellings. By the end of the 13th century, the Ancestral Puebloans abandoned the cliff dwellings, and an examination of tree trunks indicates that a severe drought occurred between 1276 and 1299.

Poverty Point: An Archaic Engineering Marvel

Here’s the thing about Poverty Point that makes it so mind-blowing. Indigenous people built earthen ridges and mounds between 1700 and 1100 BCE during the Late Archaic period. This wasn’t just ancient by North American standards. The Poverty Point culture flourished at the same time as the Minoan civilization, the rise in Babylon of King Hammurabi, and the rule of Akhenaton and Queen Nefertiti in Egypt.

Men and women shaped nearly 2 million cubic yards of soil into stunning landscapes, resulting in a massive 72-foot-tall mound and enormous concentric half-circles. The central site features remarkable earthworks, including six concentric half-hexagonal embankments, which served various social, ceremonial, and possibly astronomical purposes. What makes this even more remarkable is the context. The Poverty Point inhabitants built a complex array of earthen mounds and ridges overlooking the Mississippi River flood plain, which is particularly impressive for a pre-agricultural society.

Research revealed that this culture was primarily a highly organized hunter-gatherer society, known for extensive trade networks spanning the eastern half of North America, and archaeologists believe Poverty Point was a major commercial hub. Poverty Point was at the center of a vast exchange network, with more than 78 tons of rocks and minerals brought from as far as 800 miles away. It is a remarkable achievement in earthen construction in North America that was unsurpassed for at least 2,000 years.

The Hopewell Tradition and Ceremonial Earthworks

Travel to the river valleys of southern Ohio and you’ll encounter something truly extraordinary. Eight monumental earthen enclosure complexes built between 2,000 and 1,600 years ago are the most representative surviving expressions of the Hopewell culture, with scale and complexity evidenced in precise geometric figures as well as hilltops sculpted to enclose vast, level plazas.

An earthen circle large enough to contain the Empire State Building on its side, and an octagonal earthwork capable of holding four Roman Coliseums stand among these wonders. I know it sounds crazy, but the Octagon has sides enclosing approximately 50 acres and openings that mark the major rising and setting points of the moon over an 18.6-year cycle. This level of astronomical knowledge and engineering precision challenges many assumptions about prehistoric societies.

The Hopewell culture flourished from about 200 BCE to 500 CE chiefly in what is now southern Ohio, with related groups in Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa. Their metalwork has been called the finest in pre-Columbian North America, using copper sheet extensively along with some silver, meteoric iron, and occasionally gold. Trade routes were evidently well developed, as material from as far away as the Rocky Mountains and the coasts of the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean are found in Hopewell sites. Despite having no written language nor centralized form of government, the Hopewells periodically gathered from tiny villages scattered across great distances to erect these elaborate structures, one basketful of dirt at a time.

The Adena Culture: First of the Mound Builders

Before the Hopewell came another group whose achievements set the stage for everything that followed. The Adena culture took form in the Ohio River valley from 1000 BC to 100 AD, and Adena people erected earthworks and mounds in present-day Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania. The Adena were the first ancient American culture with wide-ranging influence, known for their conical burial mounds and shared concept of an afterlife.

They also might have been the continent’s first habitual tobacco smokers. Think about that for a moment. While the archaeological record provides clues about their spiritual practices and social organization, much remains mysterious. The Adena culture and the ensuing Hopewell tradition built monumental earthwork architecture and established continent-spanning trade and exchange networks.

The Adena developed sophisticated burial practices that would influence later cultures. Their conical mounds often contained multiple burials, with grave goods that demonstrated both artistic skill and far-reaching trade connections. Unlike later mound-building cultures, the Adena seemed more focused on vertical construction, stacking burials atop one another over generations.

Networks of Trade and Cultural Exchange

One aspect that truly unites these forgotten civilizations is the vast web of connections they maintained across enormous distances. The scale of trade would impress even modern logistics experts. Many raw materials used at Poverty Point, such as slate, copper, galena, jasper, quartz, and soapstone, came from as far as 620 miles away.

The Hopewell culture is known for a network of contacts stretching from the Atlantic coast to the Rocky Mountains, bringing materials such as mica, shark’s teeth, obsidian, copper, and shells to Ohio. Consider what this means. Without horses, without wheels, without modern transportation of any kind, these societies moved precious materials across half a continent. Mississippian culture pottery and stone tools in the Cahokian style were found at the Silvernale site near Red Wing, Minnesota, and materials from Pennsylvania, the Gulf Coast, and Lake Superior have been excavated at Cahokia.

These weren’t isolated villages struggling for survival. They were interconnected societies participating in what archaeologists now recognize as one of the most extensive trade networks in the ancient world. The movement of exotic goods also facilitated the spread of ideas, artistic styles, and religious practices. Shared symbols appear across vast distances, hinting at common spiritual beliefs or ceremonial practices that linked these diverse peoples.

The Mystery of Their Disappearance

Perhaps the most haunting aspect of these civilizations is their abandonment and decline. Cahokia’s rapid expansion has been called a great civilizing social movement, but this big bang did not last, and only one hundred years after its peak the waning began, with the Mississippian world collapsing around 1200 AD. The great earthen mounds remained on the landscape, silent witnesses to what had been.

Toward the end of the 13th century, some cataclysmic event forced the Anasazi to flee their cliff houses and homeland to move south and east, becoming the greatest puzzle facing archaeologists who study the ancient culture. Changes in temperature, precipitation, and increased flooding may have caused an ecological imbalance that led to the abandonment of Poverty Point. After about 400 CE the more spectacular features of the Hopewell culture gradually disappeared, and the quantity and quality of fine articles and mounds declined.

Climate change, resource depletion, social upheaval, warfare, disease. Scholars debate the causes, but the results remain undeniable. Thriving centers of population, commerce, and ceremony were abandoned, sometimes seemingly overnight. By the time European explorers arrived centuries later, the descendants of these civilizations had scattered, and the connections to the mound builders had grown dim. Early Anglo settlers promulgated a myth of the moundbuilders, arguing that the simple tribes they saw could not possibly have built the mound-marked landscape, until indisputable evidence proved the contemporary Indians were related to the ancient peoples.

Conclusion: Reclaiming a Hidden Legacy

The civilizations that flourished across prehistoric North America deserve recognition alongside the great societies of antiquity. They built monuments that still impress modern engineers, established trade networks spanning thousands of miles, created sophisticated artwork, and developed complex social and spiritual systems. Cahokia is the largest pre-Columbian settlement north of Mexico and the pre-eminent example of a cultural, religious, and economic centre of the Mississippian culture. Poverty Point is an outstanding example of landscape design and monumental earthwork construction by a population of hunter-fisher-gatherers.

These achievements didn’t happen in isolation. They represent centuries of accumulated knowledge, cooperative effort, and cultural innovation by Indigenous peoples. When you stand before Monks Mound, walk the ridges of Poverty Point, or gaze up at the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde, you’re witnessing testaments to human ingenuity that have endured for over a thousand years. These forgotten civilizations weren’t primitive or simple. They were dynamic, sophisticated, and deeply connected to the land and cosmos around them.

The story is finally being told with the respect and wonder it deserves. What other secrets might still be waiting beneath the soil, ready to reshape our understanding once again?