Picture this: you’re standing in the Morrison Formation 150 million years ago, and the ground trembles beneath your feet. Through the ancient ferns and cycads, you spot them—a massive Allosaurus, its razor-sharp teeth gleaming in the Jurassic sun, locked in a deadly stare-down with an equally imposing Stegosaurus, its tail spikes bristling with menace. This isn’t just some Hollywood fantasy; it’s a confrontation that paleontologists believe actually happened in prehistoric North America. The question that’s been haunting researchers for decades is simple yet electrifying: in this ultimate showdown between predator and prey, who would emerge victorious?

The Gladiators of the Jurassic Arena

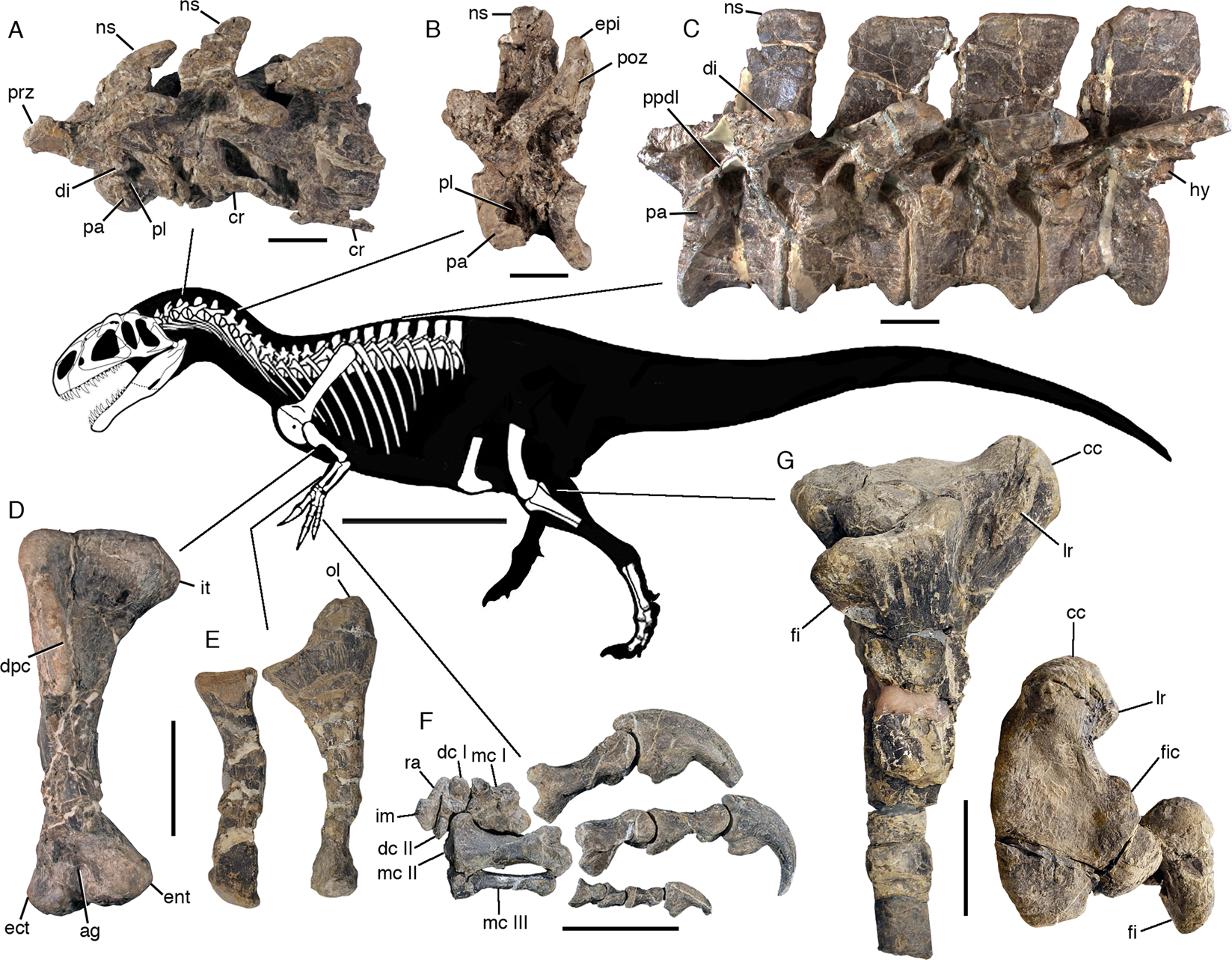

The Late Jurassic period was nature’s ultimate battleground, where titans clashed in what we now call the Morrison Formation. Allosaurus fragilis, the apex predator of its time, ruled these ancient landscapes with ruthless efficiency. Standing up to 28 feet long and weighing around 4,000 pounds, this carnivorous beast was built for one purpose—killing.

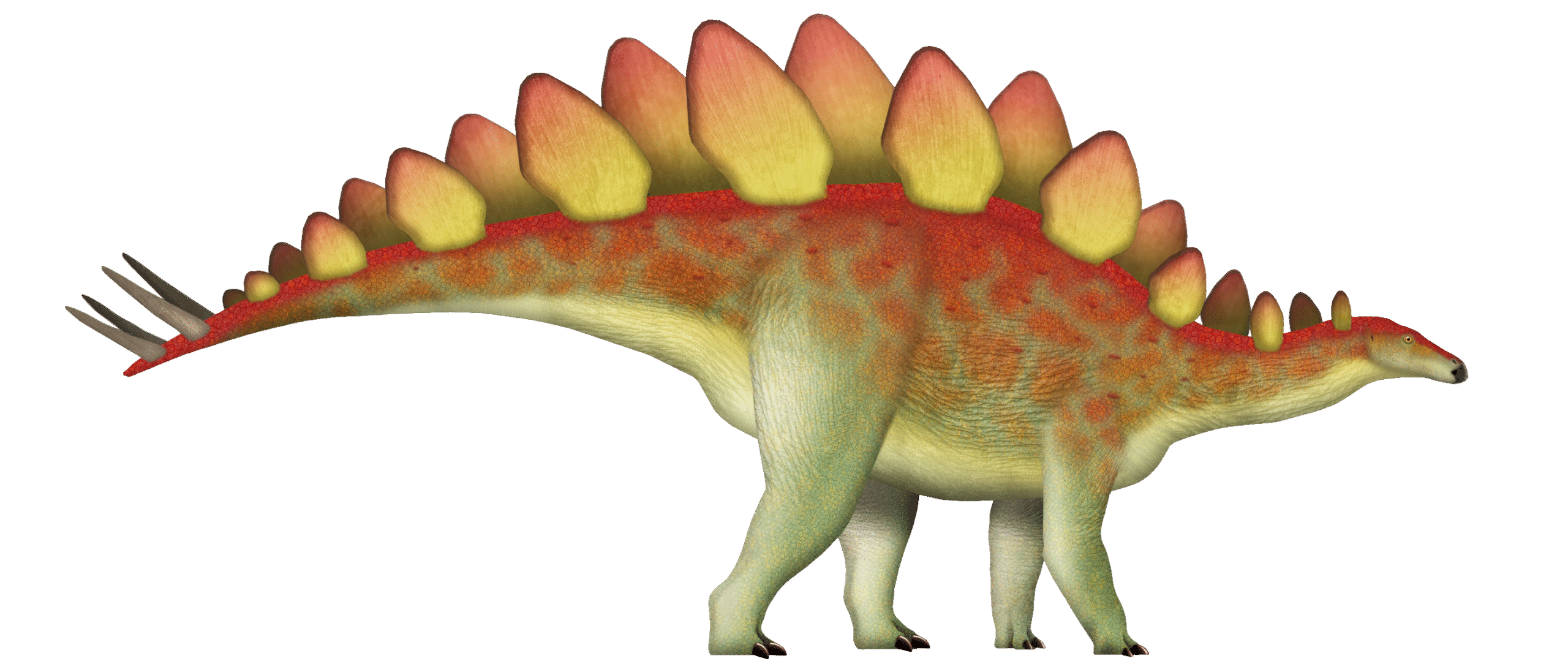

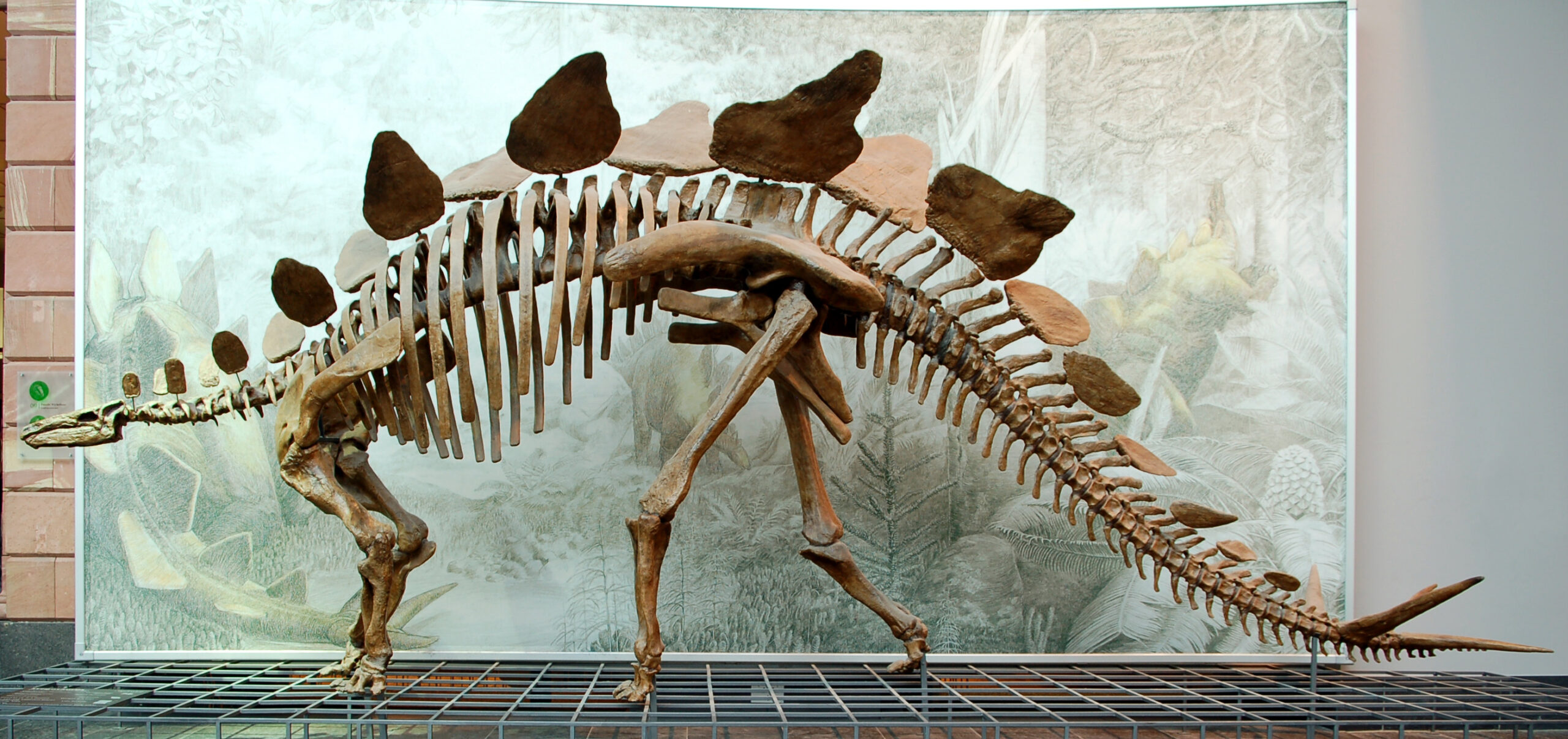

On the other side of this prehistoric coin stood Stegosaurus stenops, an armored herbivore that was no pushover. Measuring up to 30 feet in length and tipping the scales at nearly 5 tons, this plant-eater was essentially a living fortress. The stage was set for epic confrontations that would make today’s nature documentaries look like children’s cartoons.

What makes this matchup so fascinating isn’t just the size difference—it’s the complete contrast in survival strategies. We’re talking about speed versus armor, agility versus brute force, surgical precision versus devastating power.

Allosaurus: The Perfect Killing Machine

When you examine Allosaurus closely, you’re looking at millions of years of evolutionary refinement focused on one goal: efficient predation. This dinosaur’s skull alone tells a story of devastating hunting prowess. Armed with 70 razor-sharp, serrated teeth that could slice through flesh like butter, Allosaurus possessed a bite force estimated at around 3,572 pounds per square inch.

The predator’s long, powerful legs could propel it at speeds reaching 25 miles per hour—fast enough to overtake most prey in short bursts. Its muscular tail served as a perfect counterbalance, allowing for sharp turns and sudden direction changes during pursuit. Those massive arms, ending in three-fingered hands with 8-inch claws, were designed for grappling and holding struggling prey.

But here’s what really sets Allosaurus apart: its brain-to-body ratio was remarkably high for a dinosaur. This suggests sophisticated hunting strategies, possibly including pack coordination and tactical ambush techniques. Recent studies of fossilized brain cases reveal enlarged regions associated with vision and coordination, painting a picture of a predator that was both physically and mentally equipped for complex hunts.

Stegosaurus: The Walking Fortress

Don’t let anyone tell you that Stegosaurus was just a gentle giant munching on plants. This herbivore was armed to the teeth—or should we say, armed to the spikes. The most famous feature of Stegosaurus is undoubtedly its thagomizer, a tail weapon consisting of four massive spikes that could reach lengths of up to 3 feet each.

Those iconic plates running along its back weren’t just for show either. While their primary function was likely thermoregulation, they also served as intimidation displays and potentially offered some protection from attacks from above. The plates could flush with blood, creating a dramatic visual warning to potential predators.

What’s truly remarkable about Stegosaurus is its defensive positioning. When threatened, it would likely position itself with its rear toward the attacker, swinging that devastating tail in wide, bone-crushing arcs. The sheer physics of this defensive maneuver are mind-boggling—imagine a 10,000-pound sledgehammer swinging at 60 miles per hour, tipped with four spear points.

The Evidence Written in Stone

The Morrison Formation has given us more than just fossils—it’s provided us with a crime scene. In 1992, paleontologists discovered something that sent shockwaves through the scientific community: an Allosaurus vertebra with a perfectly preserved Stegosaurus spike embedded in it. This fossil evidence represents the smoking gun of prehistoric predation.

Even more compelling is the discovery of Stegosaurus bones bearing distinctive Allosaurus tooth marks. These bite marks, found primarily on the limbs and lower body, suggest that Allosaurus wasn’t just scavenging—it was actively hunting these armored giants. The positioning of these marks indicates strategic attacks aimed at vulnerable areas.

Recent excavations have uncovered what appears to be a mass death assemblage, with multiple Allosaurus and Stegosaurus remains found in close proximity. While this could represent a drought-induced gathering around a water source, some researchers propose it might be evidence of a coordinated hunting event gone wrong.

Size Matters: The Physics of Prehistoric Combat

When it comes to prehistoric combat, size isn’t everything—but it’s definitely something. Stegosaurus had a significant weight advantage, outweighing Allosaurus by nearly 2,000 pounds. This mass difference meant that in a head-on collision, physics would favor the herbivore. Think of it like a motorcycle hitting an SUV—momentum matters.

However, Allosaurus had advantages that went beyond simple mass. Its center of gravity was positioned for optimal maneuverability, while Stegosaurus was built more like a living tank—powerful but not particularly agile. The predator’s longer legs and more flexible spine meant it could potentially outmaneuver its prey, striking from unexpected angles.

The height difference also played a crucial role. Allosaurus stood taller on its hind legs, giving it a potential advantage in reaching over the defensive plates to strike at the neck or back. But this same height made it vulnerable to those devastating tail spikes, which could reach up to wound the predator’s legs and lower body.

The Weapons Arsenal: Claws, Teeth, and Spikes

Allosaurus came equipped with what paleontologists call the “terrible triumvirate”—teeth, claws, and raw power. Its teeth were continuously replaced throughout its lifetime, ensuring a constant supply of sharp cutting tools. These weren’t just for show; microscopic analysis reveals wear patterns consistent with bone-crushing and flesh-tearing activities.

The predator’s hand claws were engineering marvels, curved like meat hooks and designed for maximum penetration and holding power. These weapons could inflict devastating wounds while simultaneously preventing escape. The foot claws, though smaller, were equally dangerous, capable of delivering killing blows to downed prey.

Stegosaurus countered with its own impressive arsenal. Those tail spikes weren’t just sharp—they were positioned at the perfect angle and height to target an attacking Allosaurus’s legs and lower torso. The spikes could potentially cause massive internal bleeding or even break bones with their tremendous impact force.

Hunting Strategies: Ambush vs. Confrontation

Modern predator-prey relationships give us clues about how these ancient encounters might have played out. Allosaurus likely employed ambush tactics, using terrain and vegetation to mask its approach. The Morrison Formation’s landscape, with its river systems and dense plant growth, provided perfect cover for a patient predator.

The key to success for Allosaurus would have been avoiding that deadly tail. This meant either attacking from the front—a risky proposition given Stegosaurus’s size—or somehow getting alongside the herbivore where the tail’s reach was limited. Some researchers propose that Allosaurus might have used pack hunting strategies, with multiple individuals attacking from different angles.

Stegosaurus, on the other hand, likely relied on early detection and defensive positioning. With its small brain, it couldn’t employ complex strategies, but its defensive instincts were probably finely tuned. The herbivore’s best chance lay in keeping its rear end toward any threat and using those tail spikes to create a deadly perimeter.

The Anatomical Weak Points

Every warrior has vulnerabilities, and these Jurassic giants were no exception. For Stegosaurus, the most obvious weak point was its small head and relatively exposed neck. The brain, roughly the size of a walnut, was protected by limited skull armor. A successful attack to this area could potentially be fatal.

The herbivore’s sides, though partially protected by the plates, were still vulnerable to a determined attacker. The legs, while powerful, were also potential targets—a mobility kill could leave Stegosaurus helpless against a persistent predator.

Allosaurus had its own Achilles’ heels. Those long, powerful legs were perfect for running but became massive targets when within range of Stegosaurus’s tail. A single well-placed spike could shatter a femur or sever major blood vessels. The predator’s relatively light build, while advantageous for speed, made it vulnerable to the herbivore’s massive bulk.

Behavioral Clues from Modern Analogies

Looking at modern predator-prey relationships provides fascinating insights into how these ancient encounters might have unfolded. Lions occasionally take down Cape buffalo, animals that significantly outweigh them and possess dangerous horns. The key is usually patience, teamwork, and targeting the young or weak.

Similarly, Allosaurus might have focused on juvenile or injured Stegosaurus individuals. A full-grown, healthy Stegosaurus would have been a formidable opponent, but a young one lacking full spike development or an injured adult might have been more manageable prey.

The seasonal patterns we see in modern ecosystems also likely applied to the Jurassic. During dry seasons, when herbivores were forced to travel long distances to water sources, they became more vulnerable to predation. Allosaurus may have capitalized on these moments of weakness.

The Environmental Factor

The Morrison Formation’s environment played a crucial role in these prehistoric encounters. The landscape featured river systems, flood plains, and dense vegetation that could either help or hinder both predator and prey. Open areas favored Allosaurus, providing space for pursuit and maneuvering.

Dense vegetation, however, could work in Stegosaurus’s favor by limiting the predator’s approach routes and providing early warning through sound and movement. The herbivore’s lower profile might have allowed it to navigate through brush that would slow down the taller Allosaurus.

Water sources were likely hotspots for these encounters. Stegosaurus, needing to drink regularly, would have been vulnerable during these necessary visits. Allosaurus, understanding this pattern, might have used watering holes as ambush sites, much like modern crocodiles do today.

The Numbers Game: Pack Hunting Evidence

One of the most intriguing aspects of this prehistoric puzzle is the possibility of pack hunting. While Allosaurus was traditionally viewed as a solitary predator, recent fossil evidence suggests otherwise. Multiple Allosaurus fossils found in close proximity, along with bite marks on each other’s bones, hint at complex social behaviors.

If Allosaurus did hunt in coordinated groups, it would have dramatically shifted the balance of power. A single Stegosaurus, no matter how well-armed, would have struggled against multiple attackers approaching from different angles. This strategy would have been particularly effective against the herbivore’s limited maneuverability.

The logistics of pack hunting would have required sophisticated communication and coordination. Recent brain case studies suggest Allosaurus possessed the neural complexity for such behaviors, making coordinated hunting a distinct possibility rather than mere speculation.

Fossil Fight Club: The Smoking Gun Evidence

The most compelling evidence for Allosaurus-Stegosaurus combat comes from a remarkable fossil discovered in Colorado. This specimen shows an Allosaurus caudal vertebra with a Stegosaurus tail spike embedded so deeply that the bone had begun to heal around it. The predator had survived this encounter, at least temporarily.

This fossil tells an incredible story of survival and adaptation. The Allosaurus had taken a potentially fatal wound but managed to escape and live long enough for the bone to begin healing. It raises questions about the frequency of these encounters and the survival rates of both species.

Additional specimens show Stegosaurus fossils with bite marks matching Allosaurus tooth spacing, found primarily on the limbs and lower body. These marks suggest systematic attacks aimed at disabling the herbivore rather than quick kills, indicating that Allosaurus had developed specific strategies for dealing with armored prey.

The Verdict: David vs. Goliath Revisited

After examining all the evidence, the question isn’t whether Allosaurus could take down a Stegosaurus—it’s under what circumstances this might have been possible. The fossil record clearly shows that these encounters happened, and sometimes the predator emerged victorious.

However, success would have depended on numerous factors: the age and health of the Stegosaurus, the hunting strategy employed, environmental conditions, and perhaps most importantly, whether Allosaurus hunted alone or in groups. A healthy adult Stegosaurus would have been a formidable opponent for any single predator.

The evidence suggests that while Allosaurus certainly attempted to hunt Stegosaurus, it was likely a high-risk, high-reward strategy. The potential for catastrophic injury was enormous, but so was the payoff—a single successful kill could feed a predator for weeks. In the harsh world of the Late Jurassic, sometimes the biggest gambles offered the greatest rewards.

When you consider all the factors—size, weaponry, strategy, and sheer prehistoric determination—it becomes clear that both these magnificent creatures were perfectly adapted for their roles in one of nature’s most epic confrontations. The hunt was definitely on, and sometimes, against all odds, the hunter became the hunted.