When we think of dinosaurs, our minds often conjure images of towering behemoths like Brachiosaurus or the fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex. However, the Mesozoic Era was home to a remarkable diversity of dinosaur species, many of which remained surprisingly small throughout their evolutionary history. These diminutive dinosaurs, some no larger than modern chickens or dogs, thrived alongside their gigantic cousins for millions of years. Their success challenges our assumptions about dinosaur evolution and reveals fascinating adaptations that allowed these “lightweights” to carve out their ecological niches in a world of giants. From quick, agile predators to specialized plant-eaters, these smaller dinosaurs represent an often-overlooked but crucial part of prehistoric ecosystems.

The Scale of “Small” in Dinosaur Terms

When paleontologists describe a dinosaur as “small,” they’re using a relative scale that might surprise many people. Small dinosaurs typically weighed between 2 and 100 kilograms (4.4 to 220 pounds), with some species weighing even less. The chicken-sized Compsognathus, for instance, weighed just about 3 kilograms (6.6 pounds) and measured roughly 1 meter (3.3 feet) in length, including its tail. Microraptor, a fascinating genus of feathered dinosaur, weighed only about 1 kilogram (2.2 pounds) when fully grown. Even among the generally large sauropods, some species like Europasaurus were considered dwarfs at “only” 2 tons – enormous by modern animal standards but miniature compared to their 70-ton relatives. This scale reminds us that the dinosaur world operated on different dimensional parameters than our modern ecosystems, with even the “small” species often outweighing many contemporary mammals.

Evolutionary Advantages of Staying Small

Maintaining a smaller body size offered numerous evolutionary advantages for certain dinosaur lineages. Smaller bodies required less food to sustain, allowing these species to survive in resource-limited environments where larger dinosaurs would struggle. Their reduced size often correlated with faster reproductive cycles and shorter generation times, enabling more rapid adaptation to changing conditions. Small dinosaurs could also exploit microhabitats inaccessible to larger species, such as dense underbrush, tree canopies, or small burrows. Many diminutive dinosaurs displayed remarkable agility and speed relative to their size, making them effective at evading predators or, in the case of carnivorous species, pursuing similarly sized prey. Perhaps most importantly, smaller species often survived ecological disruptions better than their larger counterparts, as evidenced by fossil records showing greater resilience among smaller dinosaurs during certain extinction events. These combined advantages made staying small a successful evolutionary strategy for many dinosaur lineages despite the apparent benefits of gigantism seen in other groups.

Island Dwarfism: Nature’s Miniaturization Process

Island dwarfism represents one of the most fascinating evolutionary phenomena that produced smaller dinosaur species. When populations of normally large animals become isolated on islands with limited resources, natural selection often favors smaller body sizes over generations. The classic example in dinosaurs is Europasaurus, a sauropod that lived on an island in what is now northern Germany during the Late Jurassic period. While related sauropods typically reached lengths of 20-30 meters, Europasaurus adults measured just 6-8 meters long – a dramatic size reduction. Similarly, Magyarosaurus, a titanosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Romania, evolved on a prehistoric island archipelago and reached only about one-third the size of its mainland relatives. These island-dwelling dinosaurs developed smaller bodies as an adaptation to the limited food supply and restricted territory of their insular habitats. Their reduced size allowed them to maintain viable populations in environments that simply couldn’t support full-sized versions of their species, demonstrating how powerful ecological pressures can reshape even the largest dinosaur lineages into more compact forms.

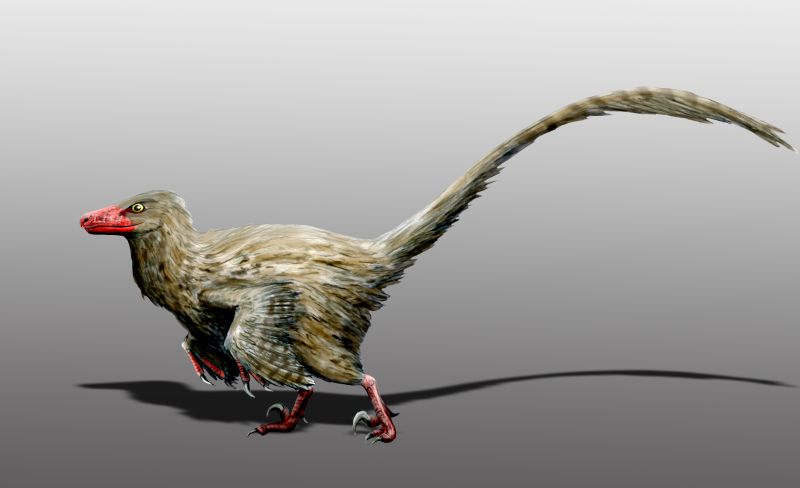

The Quick and Nimble: Small Predatory Dinosaurs

Small predatory dinosaurs occupied crucial ecological niches throughout the Mesozoic, often specializing in hunting prey that larger carnivores couldn’t efficiently pursue. Velociraptor, made famous by popular culture but only about the size of a turkey, possessed remarkable speed and agility that made it a formidable predator of small to medium-sized animals. The previously mentioned Compsognathus likely hunted lizards and small mammals with precision and quickness that larger predators couldn’t match. Microraptor, with its four wings and gliding capabilities, could pursue prey in three-dimensional space, potentially catching insects in flight or small vertebrates in trees. These diminutive hunters often displayed proportionally larger brains relative to their body size compared to giant predators, suggesting enhanced sensory processing and hunting intelligence. Their success is evidenced by the remarkable diversity of small theropod lineages throughout the Mesozoic, with new species continually being discovered by paleontologists. These lightweight predators demonstrate that in the dinosaur world, being small didn’t mean being unsuccessful – it often meant occupying specialized predatory roles with remarkable efficiency.

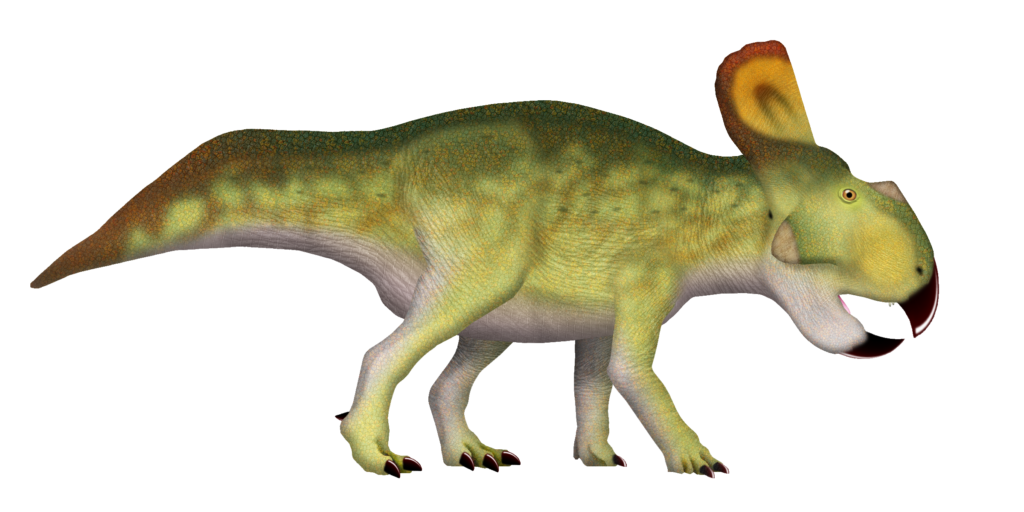

Small But Mighty: Defensive Adaptations

Despite their diminutive stature, many small dinosaurs evolved sophisticated defensive adaptations that allowed them to survive in ecosystems dominated by much larger predators. Protoceratops, a sheep-sized relative of Triceratops, possessed a formidable beak and a defensive frill that made it a challenging target despite being just 2 meters (6.5 feet) long. The dog-sized ankylosaur Minmi developed protective armor plating across its back while maintaining a relatively small body size of about 3 meters (10 feet). Some small ornithopods like Hypsilophodon compensated for their modest size with exceptional running speeds, estimated at up to 50 kilometers (31 miles) per hour. Many small dinosaurs also evolved to live in groups, gaining safety in numbers through collective vigilance and coordinated defensive behaviors. Fossil evidence suggests that even modest-sized pachycephalosaurs used their thickened skull domes not just for competition within their species but potentially as a defensive mechanism against predators. These diverse adaptations demonstrate that small dinosaurs weren’t simply vulnerable prey items but rather well-equipped survivors that could effectively defend themselves despite size disadvantages.

The Energy Equation: Metabolic Considerations

The relationship between body size and metabolism played a crucial role in determining which dinosaur lineages remained small. Smaller bodies generally require less total food, but they also lose heat more rapidly due to their higher surface-area-to-volume ratio. Evidence increasingly suggests that many small dinosaurs, particularly theropods and some ornithischians, possessed elevated metabolic rates similar to modern birds, requiring them to eat frequently to maintain body temperature and energy levels. This higher metabolism likely contributed to the activity levels and cognitive abilities that made many small dinosaurs successful hunters or efficient foragers. For herbivorous species, smaller size meant they could subsist on less abundant or lower-quality plant material than their massive counterparts needed. Fossil evidence of bone microstructure in many small dinosaur species reveals growth patterns consistent with warm-blooded metabolism, including rapid growth phases and complex vascular systems. This metabolic flexibility allowed different small dinosaur lineages to thrive in various environmental conditions, from tropical forests to seasonal temperate regions, where larger species with different metabolic demands might struggle during resource-limited periods.

Small Dinosaurs and the Evolution of Flight

Perhaps the most significant evolutionary trajectory of small dinosaurs was their pivotal role in the development of powered flight. The ancestors of birds were small theropod dinosaurs that likely weighed no more than a few kilograms. Archaeopteryx, often considered the earliest known bird-like dinosaur, measured just 50 centimeters (20 inches) in length and likely weighed under 1 kilogram. The small size of these proto-avian dinosaurs was crucial for the evolution of flight capabilities, as larger bodies would have required prohibitively large wings and immense energy expenditure to become airborne. Specimens like Microraptor, Yi qi, and Ambopteryx demonstrate how various small dinosaur lineages experimented with different flight mechanisms, from four-winged gliding to bat-like membrane wings. The reduced weight of these animals allowed even modest aerodynamic adaptations to provide significant advantages in movement and predator avoidance. Fossil evidence shows a clear pattern where flight-capable dinosaurs emerged exclusively from lineages that maintained relatively small body sizes, never exceeding about 15 kilograms even in specialized gliders. This evolutionary pathway eventually led to modern birds, representing the only dinosaur lineage to survive the end-Cretaceous extinction event – a testament to the evolutionary advantages that small size conferred.

Evolutionary Constraints: Why Some Stayed Small

Not all dinosaurs remained small by choice or advantage – some lineages faced evolutionary constraints that limited their size potential. Certain dinosaur groups inherited body plans and physiological characteristics from their ancestors that made gigantism difficult or impossible to achieve. For instance, many small ceratopsians like Psittacosaurus retained a body structure that would have been biomechanically inefficient at larger sizes without the substantial skeletal modifications seen in their giant relatives like Triceratops. Some lineages evolved in ecological contexts where selection pressures consistently favored smaller individuals, such as forest-dwelling dinosaurs that needed to navigate dense vegetation. Genetic factors likely played a role as well, with some dinosaur groups potentially lacking the genetic architecture needed to achieve the extreme growth rates and delayed maturation that characterized the largest dinosaur species. The highly specialized nature of some small dinosaurs, particularly those adapted for arboreal lifestyles or particular dietary niches, created evolutionary pathways where increasing size would have been disadvantageous. These constraints remind us that evolution doesn’t always favor increasing size and that maintaining smaller dimensions can represent a successful adaptation rather than a failure to grow larger.

Small Herbivores: Specialized Plant-Eaters

Small herbivorous dinosaurs developed specialized feeding strategies that allowed them to thrive without competing directly with larger plant-eaters. Leaellynasaura, a refrigerator-sized ornithopod from prehistoric Australia, possessed large eyes adapted for the low light conditions of polar forests, allowing it to feed on vegetation during the dark winter months when other dinosaurs might have been less active. The turkey-sized Heterodontosaurus had a specialized jaw apparatus with different types of teeth, including prominent canine-like tusks, that enabled it to process tough plant material despite its small size. Hypsilophodon and related small ornithopods likely focused on selecting high-quality, nutrient-rich parts of plants rather than consuming large quantities of lower-quality vegetation, as many larger herbivores did. Some small herbivorous dinosaurs may have engaged in selective browsing on fungi, fruits, seeds, and young shoots – resources too limited to sustain gigantic species but sufficient for maintaining populations of modest-sized animals. Fossil evidence of gut contents and coprolites (fossilized feces) indicates that many small herbivorous dinosaurs had efficient digestive systems capable of extracting maximum nutrition from relatively small quantities of plant matter. These diverse feeding adaptations demonstrate how small herbivorous dinosaurs carved out ecological niches distinct from their massive relatives.

The Smallest of the Small: Microdinosaurs

At the end of dinosaur miniaturization were truly tiny species that pushed the lower boundaries of dinosaur body size. Parvicursor, whose name means “small runner,” was a theropod dinosaur from Mongolia that measured just 39 centimeters (15 inches) in length and likely weighed less than a pound. The recently described Ambopteryx was a strange, bat-winged dinosaur approximately the size of a modern blue jay. Epidexipteryx, a bizarre feathered dinosaur from China, was roughly the size of a pigeon and possessed elongated ribbon-like tail feathers, unlike anything seen in modern birds. Paleontologists continue discovering even smaller dinosaur species, particularly from exceptionally preserved fossil beds in China, Mongolia, and Argentina. These microdinosaurs often display highly specialized anatomies adapted for particular lifestyles, such as insect hunting, seed eating, or gliding between trees. Their small size allowed them to exploit ecological niches unavailable to larger dinosaurs, such as living in the forest canopy or feeding on food sources too small to sustain bigger animals. The existence of these dinosaurian minimalists demonstrates the remarkable evolutionary plasticity of dinosaur lineages and challenges our traditional image of dinosaurs as universally massive creatures.

Small Dinosaurs in Different Ecosystems

Small dinosaur species adapted to thrive in a remarkable variety of prehistoric ecosystems throughout the Mesozoic Era. In dense forest environments, diminutive dinosaurs like Mei long and Sinosauropteryx navigated the undergrowth with agility that larger species couldn’t match. Coastal and shoreline habitats supported small species like Hesperonychus, which likely hunted among tidepools and marshes for fish, crustaceans, and other marine-adjacent prey. Desert-adapted small dinosaurs such as Mononykus developed specialized limbs and feeding adaptations to survive in resource-limited arid environments. The polar regions of both prehistoric northern and southern hemispheres hosted uniquely adapted small dinosaurs like Leaellynasaura and Nanuqsaurus, capable of surviving seasonal darkness and cooler temperatures. Even in montane environments, preserved evidence of small dinosaur species suggests that they could navigate steep terrain more effectively than their massive counterparts. These ecological distributions demonstrate that small dinosaurs weren’t restricted to particular habitats but rather represented successful adaptations across virtually every terrestrial ecosystem of the Mesozoic world. Their fossil remains serve as indicators of ancient environmental conditions and help paleontologists reconstruct the complex ecological communities of prehistoric Earth.

Small Dinosaurs and Mass Extinctions

The relationship between body size and survival during extinction events offers fascinating insights into dinosaur evolution. During the end-Triassic extinction approximately 201 million years ago, smaller dinosaur species appear to have fared better than many larger archosaurs, potentially contributing to dinosaurs’ subsequent dominance in the Jurassic period. Throughout the Mesozoic, minor extinction pulses tended to affect larger specialist species more severely than smaller generalists, who could often adapt to changing conditions more rapidly due to their shorter generation times and lower resource requirements. When the catastrophic end-Cretaceous extinction occurred 66 million years ago, virtually all dinosaurs except for certain small avian species (birds) perished. Recent research suggests that the small body size, flight capability, and seed-based diets of these avian dinosaurs were crucial factors in their survival when their larger relatives perished. The seeds they ate could sustain them when other food sources disappeared, and their flight abilities allowed them to escape localized disasters. Some evidence indicates that even among the birds, it was primarily the smaller ground-dwelling species that survived the extinction event, reinforcing the survival advantage that modest size provided. This pattern across multiple extinction events suggests that smaller dinosaur species possessed inherent resilience that their gigantic relatives lacked when facing severe environmental disruptions.

The Legacy of Small Dinosaurs: Birds Today

The most successful dinosaurs on Earth today are undoubtedly birds – the living descendants of small theropod dinosaurs that maintained relatively modest dimensions throughout their evolution. With approximately 10,000 living species, birds represent the most diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates and inhabit virtually every ecosystem on the planet. Their small size, inherited from their dinosaurian ancestors, enables them to fly efficiently and occupy specialized ecological niches unavailable to larger animals. The smallest modern birds, like the bee hummingbird, weighing just 2 grams, demonstrate the extreme miniaturization possible within the dinosaur family tree. Even the largest living birds, such as ostriches and condors, remain modest-sized compared to many of their extinct dinosaur relatives. The respiratory system of birds, with its efficient air sacs and unidirectional airflow, evolved in their small theropod ancestors and proved crucial for powering their high-energy lifestyles. Modern avian metabolism, with its elevated body temperature and rapid food processing, similarly traces back to adaptations that first appeared in small non-avian dinosaurs. This living legacy demonstrates that the evolutionary strategy of remaining small wasn’t merely a side path in dinosaur evolution but rather the approach that ultimately produced the most enduring and diverse dinosaur lineage of all time.