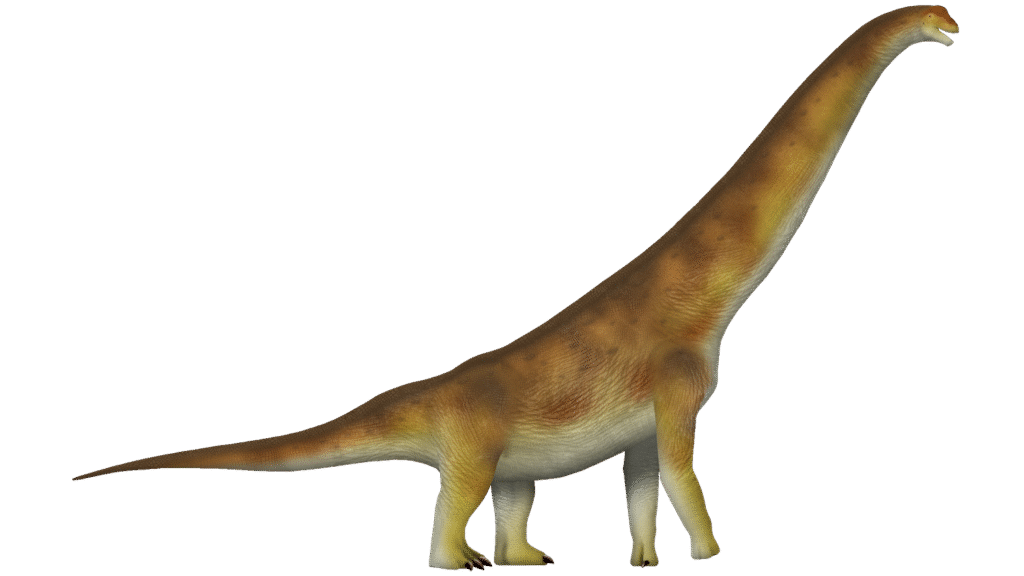

When you think of dinosaurs, what comes to mind? Perhaps the ferocious Tyrannosaurus rex or the armored Stegosaurus. Yet the true giants of the Mesozoic world were the sauropods, those impossibly long-necked behemoths that once roamed every continent. These creatures weren’t just big. They were complicated, fascinating beings with secrets that paleontologists are only beginning to unravel.

Most of us imagine sauropods as solitary wanderers, slowly munching on ancient plants with brains barely larger than walnuts. That mental image misses so much of the story. These animals lived intricate social lives, employed surprising feeding strategies, and solved biological puzzles that modern science still struggles to fully explain. Let’s be real, they were engineering marvels wrapped in scales.

Herding Together: The Surprising Social World

You might picture these titans as lone giants, but fossil evidence shows that sauropod trackways progressed in parallel directions toward a common objective, suggesting herding behavior. It’s hard to say for sure, but imagine the ground shaking as dozens of these creatures moved in coordinated groups across ancient floodplains.

Some sites contain assemblages of entirely juvenile sauropods, implying social partitioning by age. This is fascinating because it suggests these dinosaurs weren’t simply mindless plant-eating machines. Certain species like Alamosaurus seemed to group together in small herds as juveniles and either become solitary or form age-segregated adult herds. Think about that: teenage sauropods hanging out together, separate from the adults. The parallels to modern animal behavior are striking.

Colonial Nesting: Returning to the Same Spot

Nesting sites discovered in the late twentieth century reveal dozens to thousands of nests and eggs that were possibly used for thousands of years by evolving populations. Recent discoveries indicate social cohesion throughout life and age-segregation within herd structures, alongside colonial nesting behavior.

These weren’t random egg deposits. Colonial nesting behavior has been reported for sauropods, indicated by extensive clutches and morphologically similar eggs. The sheer organization required is mind-boggling. Fossil evidence suggests that herds of some titanosaurs returned to the same nesting site year after year. Generation after generation, these creatures found their way back home, a behavior more sophisticated than we once credited them with.

Parental Care: Did They Stay or Did They Go?

Here’s where things get contentious among paleontologists. Since segregation of juveniles and adults took place soon after hatching, species with age-segregated herds likely would not have exhibited much parental care, though scientists studying age-mixed herds suggested extended care before reaching adulthood.

For some groups like sauropods, we don’t have evidence of post-laying care, as researchers have no evidence that parents stuck around. The tiny titanosaur was mobile at hatching and less reliant on parental care than other animals. It appears baby sauropods hit the ground running, so to speak. Honestly, it’s a bit sad to imagine these hatchlings fending for themselves immediately, but that’s the evidence we’ve got.

Diet Detective Work: What Did They Actually Eat?

A cololite associated with a Diamantinasaurus specimen provides the first direct empirical evidence of herbivory in sauropods, demonstrating generalist feeding and minimal oral processing of food. For decades, scientists assumed these animals were herbivores based on their anatomy alone. Now we finally have proof from fossilized gut contents.

Horsetails, which were widespread during the Jurassic period, released more energy than any other plant group when tested. That’s right: these unassuming spore-bearing plants might have been the dinosaur equivalent of a power bar. Morrison Formation Diplodocus consumed monilophytes like ferns whereas Camarasaurus showed evidence for higher browsing with more woody, probably coniferous material. Different species, different menus.

Those Peculiar Teeth and Beaks

Sauropods had very simple teeth unlike any other known herbivores extinct or living, instead linking tooth complexity to replacement rates. You’d expect plant eaters to have complex grinding teeth, right? Nope. Sauropods took a completely different evolutionary path.

Camarasaurus had a robust skull and strong bite for tough leaves and branches, while Diplodocus had a weaker bite and delicate skull restricted to softer foods like ferns. Research on seven sets of tooth rows from sauropods including Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus, and Apatosaurus suggests paleontologists may have had the faces wrong, as the behemoths likely had turtlelike beaks. The mental image just shifted, didn’t it?

The Neck Enigma: More Than Just Reaching High

Long necks of sauropods have been subject to many studies regarding posture and flexibility, with length varying among groups. For years, artists depicted these animals with gracefully curved necks reaching into treetops. The reality was probably more horizontal and less swan-like.

Sauropod necks were probably less flexible than previously thought, though studies analyzing flexibility in Apatosaurus and Diplodocus revealed complexities. When activated bilaterally, oblique muscles kept the neck balanced in an energy-saving upright posture, though long cervical ribs in brachiosaurids seemed to have limited flexibility. The neck wasn’t just a feeding tool. It was a complex biomechanical system that had to balance weight, flexibility, and energy conservation.

The Cardiovascular Challenge: Pumping Blood Uphill

This is where things get seriously complicated. Hypothesized upright neck postures require systemic arterial blood pressures reaching 700 mmHg at the heart, meaning their left ventricles would have weighed 15 times those of similarly sized whales.

As cervical ribs flexed, muscle would have pushed on air sacs wrapped around the vertebral artery, acting as an accessory pump to the heart. That’s elegant problem-solving. As the neck got longer, more skeletal muscle provided more pump, meaning extreme sauropods would have had plenty of extra power to keep blood pumping. The neck literally paid for itself in terms of circulatory support.

Growth Rates: From Hatchling to Colossus

Giant sauropods reached nearly full size in as little as 12 years. Think about that timeline. A creature weighing potentially dozens of tons achieved its adult size faster than most humans reach puberty. The metabolic demands must have been staggering.

Features indicate Rapetosaurus grew as rapidly as a newborn mammal, with the newly hatched specimen weighing around 3.5 kilograms. From roughly the weight of a house cat to potentially 20 tons or more in little over a decade. That’s not just growth. That’s explosive development requiring enormous food intake and efficient digestion.

The Unanswered Questions That Keep Scientists Guessing

Despite anatomical clues indicating some sauropods held their heads high, paleontologists have yet to solve the mystery of how dinosaurs solved biological problems involving bloodflow, as the cardiovascular system remains a field of speculation. We have the bones, we have computer models, yet fundamental questions persist.

Analysis shows it would have required the animal to expend approximately half of its energy intake just to circulate blood if the neck was vertical, making it energetically more feasible to use a more horizontal neck. This is the kind of biological constraint that forces us to reconsider those iconic museum poses. Form follows function, even millions of years later.

Conclusion: Giants With Hidden Depths

The more we learn about sauropods, the more complex they become. These weren’t dim-witted eating machines trudging through prehistoric swamps. They were sophisticated animals with social structures, specialized diets, remarkable cardiovascular adaptations, and growth rates that defy easy explanation. Findings add to the perception of sauropods as fast-growing and autonomous giants with manifold facets of reproductive and social behavior.

Every fossil discovery, every biomechanical model, every comparative study with modern animals peels back another layer of mystery. The sauropods lived secret lives that we’re only now beginning to glimpse, and honestly, that makes them even more remarkable than the towering skeletons suggest. What other surprises are still buried in the rock, waiting to rewrite what we think we know about the largest land animals that ever lived?