The history of paleontology is filled with remarkable stories where chance, luck, and happy accidents have led to some of the most significant fossil discoveries in scientific history. While modern paleontology relies on methodical research and advanced technologies, many pivotal finds throughout history occurred when someone simply stumbled upon something extraordinary. From children playing in fields to construction workers breaking ground for new buildings, these accidental discoveries have revolutionized our understanding of prehistoric life and Earth’s history. The serendipitous nature of these finds reminds us that sometimes the most significant scientific breakthroughs happen not in laboratories or during planned expeditions, but in moments of unexpected fortune when the past emerges from beneath our feet.

The Nature of Serendipity in Paleontology

Serendipity—the occurrence of fortunate discoveries by accident—plays a surprisingly crucial role in the field of paleontology. Unlike controlled laboratory sciences, paleontology often relies on chance encounters with fossils that have remained hidden for millions of years. These accidents of discovery happen when the right combination of erosion, exposure, and human presence converge at the perfect moment in time. Professional paleontologists acknowledge that even with advanced techniques for locating fossil-bearing formations, many groundbreaking discoveries still occur through fortuitous circumstances rather than methodical searching. This element of chance adds a unique dimension to paleontology that distinguishes it from other scientific disciplines, making it a field where expertise and preparation meet opportunity and luck.

Mary Anning: The Ultimate Accidental Fossil Hunter

Perhaps no figure better embodies serendipitous fossil discovery than Mary Anning, whose remarkable finds along the Dorset coast of England in the early 19th century helped establish paleontology as a scientific discipline. Anning, who began collecting fossils simply to supplement her family’s meager income, had no formal scientific training but possessed an exceptional eye for fossil specimens. Her most famous accidental discovery came in 1811 when her brother spotted a strange skull protruding from a cliff face, leading Mary to excavate the first complete ichthyosaur skeleton recognized by science. Throughout her life, Anning continued to make groundbreaking discoveries while simply walking the beaches after storms, including the first complete plesiosaur and the first British pterosaur fossil. Despite receiving little recognition during her lifetime due to her gender and social class, Anning’s accidental discoveries fundamentally changed our understanding of prehistoric marine reptiles.

The Accidental Discovery of Sue the T. Rex

One of the most famous accidental fossil discoveries occurred in 1990 when amateur fossil hunter Sue Hendrickson decided to explore a cliff face while the rest of her team fixed a flat tire in South Dakota. During this unplanned detour, Hendrickson noticed several vertebrae weathering out of the cliff and stumbled upon what would become the most complete and best-preserved Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton ever found. This magnificent specimen, later named “Sue” in her honor, consists of 250 of the approximately 380 bones in a T. rex skeleton, including a nearly intact skull. The chance discovery led to a complex legal battle over ownership before eventually selling at auction for $8.4 million to the Field Museum in Chicago. Sue’s accidental discovery not only provided unprecedented insights into T. rex anatomy but also highlighted the complex issues of fossil ownership and commercialization that continue to challenge paleontology today.

Construction Sites: Unexpected Windows to Prehistory

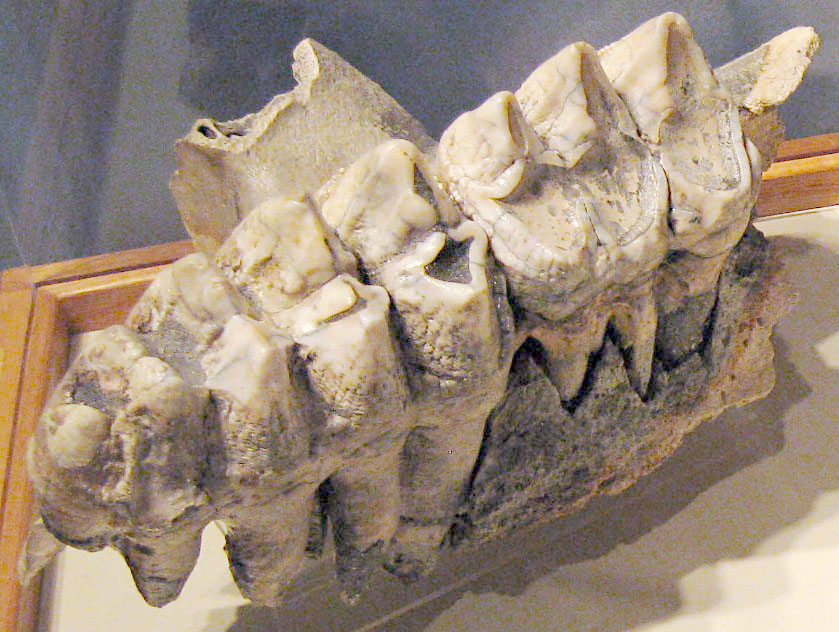

Construction projects around the world have unexpectedly unearthed some of paleontology’s most significant finds when workers simply trying to complete their jobs stumbled upon prehistoric treasures. In 2009, a bulldozer operator working at the Ziegler Reservoir expansion near Snowmass Village, Colorado, uncovered a mammoth tusk that led to one of the most important high-altitude ice age fossil sites in North America. The site ultimately yielded more than 36,000 bones from 52 different species, including mastodons, giant ground sloths, and ancient camels. Similarly, in 1993, workers digging the foundation for a housing development in San Diego County, California, accidentally exposed remains of an ancient whale along with other marine fossils dating back 3.5 million years. These construction site discoveries demonstrate how development projects, while potentially threatening paleontological resources, can also provide unprecedented access to fossil-bearing layers that might otherwise remain hidden from scientific view.

Children as Accidental Fossil Hunters

The uninhibited curiosity and ground-level perspective of children have repeatedly led to remarkable fossil discoveries throughout history. In 1824, 12-year-old William Mantell accompanied his father, amateur paleontologist Gideon Mantell, on a walk when he picked up an unusual tooth that would later be identified as belonging to an Iguanodon—one of the first dinosaurs ever described scientifically. More recently, in 2020, 4-year-old Lily Wilder was walking with her family on a beach in Wales when she spotted a perfectly preserved 220-million-year-old dinosaur footprint that experts described as “one of the best examples ever found.” Children’s natural tendency to notice small details in their environment, combined with their proximity to the ground and lack of preconceived notions about what they might find, makes them surprisingly effective fossil hunters. Many professional paleontologists credit childhood discoveries with sparking their lifelong passion for prehistoric life.

Farming: Plowing Up the Past

Agricultural activities have repeatedly led to significant paleontological discoveries when farmers, going about their daily work, unexpectedly plow up ancient remains from their fields. In 2014, a Michigan farmer named James Bristle was digging to install a drainage pipe when his equipment struck something unusual—the remains of a woolly mammoth that had been butchered by early humans approximately 15,000 years ago. The accidental discovery provided important evidence of human-mammoth interactions in North America. Similarly, in Argentina’s La Pampa Province, farmers frequently encounter giant glyptodont fossils—car-sized ancient relatives of modern armadillos—while working their fields in an area that was once prehistoric grassland. These agricultural discoveries often occur in regions that might not be the focus of dedicated paleontological expeditions, helping scientists understand the broader geographic distribution of ancient species and ecosystems that might otherwise remain unknown.

Mining Operations: Industrial Pathways to Prehistoric Life

Mining activities have inadvertently uncovered extraordinary fossils when workers penetrating deep into the Earth’s crust in search of valuable minerals instead found priceless scientific treasures. The most spectacular example may be the accidental discovery in 2011 of an exceptionally well-preserved nodosaur at the Suncor Millennium Mine in Alberta, Canada. Mine operator Shawn Funk was excavating with a mechanical shovel when he struck something unlike the surrounding rock—a dinosaur so well preserved that it has been described as a “dinosaur mummy” with intact skin, armor plates, and even stomach contents. Similarly, coal mines have frequently yielded important plant fossils and occasional animal remains that help scientists reconstruct ancient forests and swamp environments. The deep excavations and extensive rock exposure created by mining operations provide access to fossil-bearing strata that might otherwise remain inaccessible, making these industrial activities important, if accidental, contributors to paleontological knowledge.

Beach and Shoreline Discoveries

Coastlines around the world represent particularly productive zones for accidental fossil discoveries due to the constant erosion of fossil-bearing cliffs and the washing ashore of specimens. In 2011, a family walking their dogs along Lyme Regis in England—the same area where Mary Anning made her historic finds—stumbled upon a fossilized skull that turned out to belong to a 200-million-year-old ichthyosaur. The power of wave action had naturally exposed the specimen just hours before their chance encounter. Beaches along North Carolina’s coast similarly yield frequent discoveries of prehistoric shark teeth, including those of the massive megalodon, which wash ashore after storms stir up offshore sediments. These coastal discoveries often occur when storms or unusually high tides expose new material, creating brief windows of opportunity where anyone walking along the shore might make a significant find simply by glancing down at the right moment.

The La Brea Tar Pits: From Nuisance to Scientific Treasure

One of paleontology’s richest accidental discoveries began when ranchers in Los Angeles viewed the natural asphalt seeps on their property as merely an industrial resource and nuisance. The sticky tar pits had been trapping and preserving animals for tens of thousands of years, but their scientific significance wasn’t recognized until 1901 when W.W. Orcutt, a petroleum geologist, noticed fossilized bones in some excavated asphalt. What started as an industrial extraction site was revealed to be one of the world’s most important Pleistocene fossil localities, preserving over 3.5 million specimens from more than 600 species. The accidental recognition of La Brea’s scientific importance transformed our understanding of ice age ecosystems, providing unprecedented insights into predator-prey relationships and environmental change. Even today, discoveries continue to emerge from this site that was valued first for its commercial properties rather than its scientific significance.

Hobby Fossil Hunters and Citizen Science

Amateur fossil collectors pursuing their passion as a hobby have made countless significant discoveries that professional paleontologists might never have found. In 1983, amateur fossil hunter Stan Sacrison discovered what would become known as “Stan” the T. rex in South Dakota—one of the most complete tyrannosaur specimens ever found—while simply exploring areas he found interesting. In the UK, hobby fossil hunter Marie Woods was walking along the Yorkshire coast to collect shellfish in 2021 when she accidentally stumbled upon a 165-million-year-old dinosaur footprint, one of the largest and best-preserved ever found in the region. These citizen scientists, lacking formal training but possessing enthusiasm and dedication, frequently explore areas that fall outside the focus of professional research expeditions. Many museums and research institutions now actively collaborate with amateur fossil hunters through formal citizen science programs that harness this widespread interest while ensuring important discoveries are properly documented and preserved for scientific study.

The Technological Enhancement of Serendipity

While many fossil discoveries remain genuinely accidental, modern technology has created new contexts for serendipitous finds by allowing non-specialists to recognize significant specimens they might otherwise overlook. Smartphone apps that help identify fossils have enabled hikers, beachcombers, and other outdoor enthusiasts to recognize the scientific importance of objects they discover by chance. Satellite imagery and Google Earth have similarly democratized fossil hunting, with some amateur paleontologists using these tools to identify potentially fossil-rich formations before visiting them in person. In a remarkable example from 2020, a student browsing Google Earth during the COVID-19 lockdown spotted what appeared to be a fossil sticking out of the ground at Big Bend National Park in Texas, which he reported to authorities and was later confirmed as a significant find. These technological tools don’t eliminate the element of chance but instead create an expanded interface between accident and discovery, making serendipitous finds more likely to be recognized and properly reported.

From Accidents to Science: The Critical After-Discovery Phase

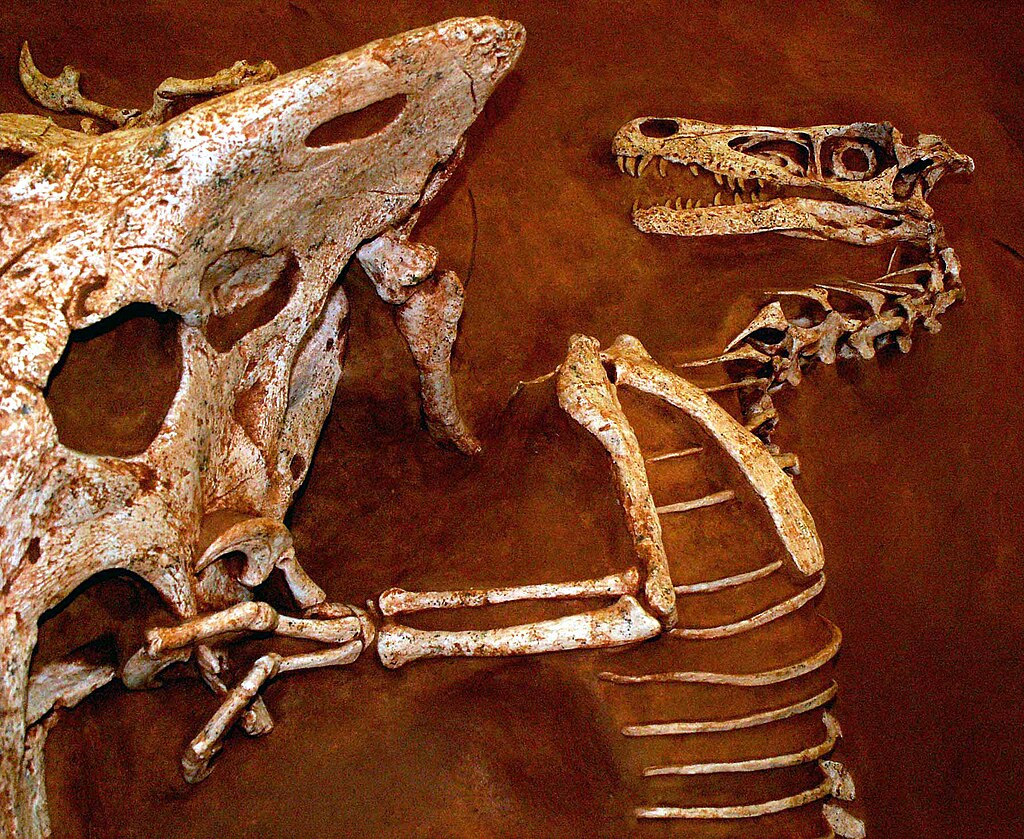

The scientific value of accidental fossil discoveries depends entirely on what happens after the initial find—a phase requiring expertise, careful documentation, and proper excavation techniques. Many significant fossil discoveries have been damaged or lost scientific value because finders attempted excavation without proper knowledge or failed to report their finds to relevant authorities. When non-specialists discover potentially important fossils, the most scientifically valuable action is to photograph the find in place, note its exact location, and contact local museums or university geology departments without attempting removal. The story of Mongolia’s famous “fighting dinosaurs”—a Velociraptor and Protoceratops preserved in combat—illustrates the importance of proper scientific follow-up, as this extraordinary specimen was nearly lost to science when initially discovered by a non-paleontologist during a 1971 expedition. Only the recognition of its significance and subsequent scientific excavation preserved this unprecedented fossil, capturing a predator-prey interaction frozen in time.

The Future of Accidental Discovery in the Digital Age

As paleontology becomes increasingly high-tech with tools like ground-penetrating radar, CT scanning, and predictive modeling, one might expect the role of accidental discovery to diminish—yet the opposite appears to be occurring. The democratization of knowledge through digital platforms has created an army of informed citizen scientists who, while not professionally trained, are increasingly aware of what constitutes a significant find. Social media and specialized online communities allow accidental discoveries to be quickly shared, identified, and reported to appropriate scientific authorities. The increased accessibility of remote or previously unexplored regions due to improved transportation infrastructure continually brings more people into potential fossil-bearing areas, increasing the statistical likelihood of chance encounters with important specimens. Rather than eliminating serendipity, modern technology appears to be expanding it by creating more informed accidental discoverers and more efficient pathways from chance encounters to scientific documentation, suggesting that happy accidents will continue to play a crucial role in paleontological discovery well into the future.

When Chance Becomes a Scientific Breakthrough

The remarkable stories of accidental fossil discoveries remind us that science sometimes advances through unexpected paths. While modern paleontology employs sophisticated technologies and methodical approaches, the element of chance—the farmer’s plow striking a mammoth tusk, the child noticing an unusual stone, or the hiker spotting bones eroding from a hillside—continues to unveil chapters of Earth’s past that might otherwise remain hidden. These serendipitous moments connect professional researchers, amateur enthusiasts, and complete novices in a shared enterprise of discovery. As technology advances and more people gain awareness of fossil identification, the potential for meaningful accidental discoveries only increases. The next major paleontological breakthrough might well come not from a planned expedition but from someone who, like Mary Anning two centuries ago, simply happens to be in the right place at the right time, with eyes open to the possibilities beneath their feet.