For centuries, dinosaurs have captivated our imagination, appearing in countless books, movies, and museum displays. Yet until relatively recently, our understanding of their external appearance—particularly their skin—was largely speculative. Today, thanks to exceptional fossil discoveries and advanced scientific techniques, paleontologists can now paint a more accurate picture of dinosaur skin textures, patterns, and colors. These rare skin impressions provide a remarkable window into the past, revealing dinosaurs not as simple scaled creatures, but as animals with complex and varied dermal coverings that served crucial biological functions.

The Rarity of Skin Impressions in the Fossil Record

Skin impressions are considered extraordinarily rare in the fossil record compared to bones and teeth. This rarity stems from the fact that soft tissues typically decompose rapidly after death, long before the fossilization process can preserve them. For skin impressions to form, very specific burial conditions must occur—typically rapid burial in fine-grained sediments that can capture subtle surface textures before decomposition. Often, these impressions form as natural molds where the actual skin is gone, but its texture has been imprinted in the surrounding sediment. Scientists estimate that less than one percent of dinosaur fossils include any skin impressions, making each discovery particularly valuable for understanding these extinct creatures’ external appearance.

How Dinosaur Skin Becomes Preserved

The preservation of dinosaur skin occurs through several pathways, each requiring exceptional circumstances. In most cases, rapid burial in fine sediments like mud or silt is essential, as these materials can capture minute details before decomposition erases them. Sometimes, skin becomes preserved through mineralization, where minerals replace the original organic material while maintaining its structure. Another pathway involves mummification, where extreme drying prevents bacterial decomposition and preserves the skin’s texture. Occasionally, skin impressions form when a dinosaur lies on soft sediment, leaving an imprint before the body decays. The resulting fossils can take the form of actual skin fragments, impressions (negative molds), or casts (positive molds) that reveal the external texture of the animal’s body covering. Without these rare preservation events, our understanding of dinosaur appearance would be much more limited.

The Discovery of Hadrosaur “Mummies”

Hadrosaurs, commonly known as duck-billed dinosaurs, have provided some of the most spectacular skin impressions in paleontology. The most famous example is “Dakota,” a Edmontosaurus found in North Dakota with approximately 90% of its skin texture preserved. These remarkable specimens are colloquially called “mummies” because of their extensive soft tissue preservation, though they’re not mummified in the traditional sense of ancient Egyptian practices. The Senckenberg hadrosaur and the “Leonardo” specimen (a juvenile Brachylophosaurus) also feature extensive skin impressions that reveal a complex pattern of scales, varying in size and arrangement across different body regions. These specimens show that hadrosaurs possessed a mosaic of scale types—small, polygonal scales covered much of the body, while larger, non-overlapping tubercles appeared in distinctive patterns along the spine and tail. The remarkable preservation of these specimens has revolutionized our understanding of hadrosaur appearance, demonstrating they had much more complex skin textures than initially thought.

Tyrannosaur Skin: Not Just Giant Lizards

Recent discoveries have dramatically altered our understanding of tyrannosaur skin texture, challenging long-held assumptions about these iconic predators. Contrary to traditional depictions as essentially giant lizards, fossilized skin impressions from tyrannosaurs reveal a more nuanced dermal covering. A particularly significant discovery came from Canada, where researchers found skin impressions associated with tyrannosaur fossils showing small, pebbly scales rather than the large, reptilian scales often depicted in earlier reconstructions. These scales varied in size across the body, with some areas showing a distinctive pattern of larger scales surrounded by smaller ones. The texture appears to have been relatively fine in many areas, creating a surface more reminiscent of modern birds’ scaly feet than typical reptile skin. These findings align with our current understanding of tyrannosaurs as theropod dinosaurs closely related to birds, and help correct decades of inaccurate portrayals in popular media and museum displays.

Sauropod Skin: Textures of the Giants

The skin of sauropods—the long-necked giants like Diplodocus and Brachiosaurus—reveals surprising diversity and specialization despite their massive size. Fossil impressions show these dinosaurs typically possessed small, non-overlapping scales arranged in a mosaic pattern across much of their bodies. Particularly intriguing is the discovery that many sauropods featured distinctive rows of larger, bump-like scales running along their sides and backs, creating a textured pattern that may have served as visual identification between species. The skin of Barosaurus and Diplodocus specimens shows these animals didn’t have uniform scaling across their massive bodies; instead, scale size and pattern varied by region, with some areas featuring rosette arrangements where a central larger scale was surrounded by smaller ones. The relatively small scale size compared to body mass likely helped with thermoregulation, as the increased surface area would have facilitated better heat exchange—a critical adaptation for animals of such enormous size navigating Mesozoic climates.

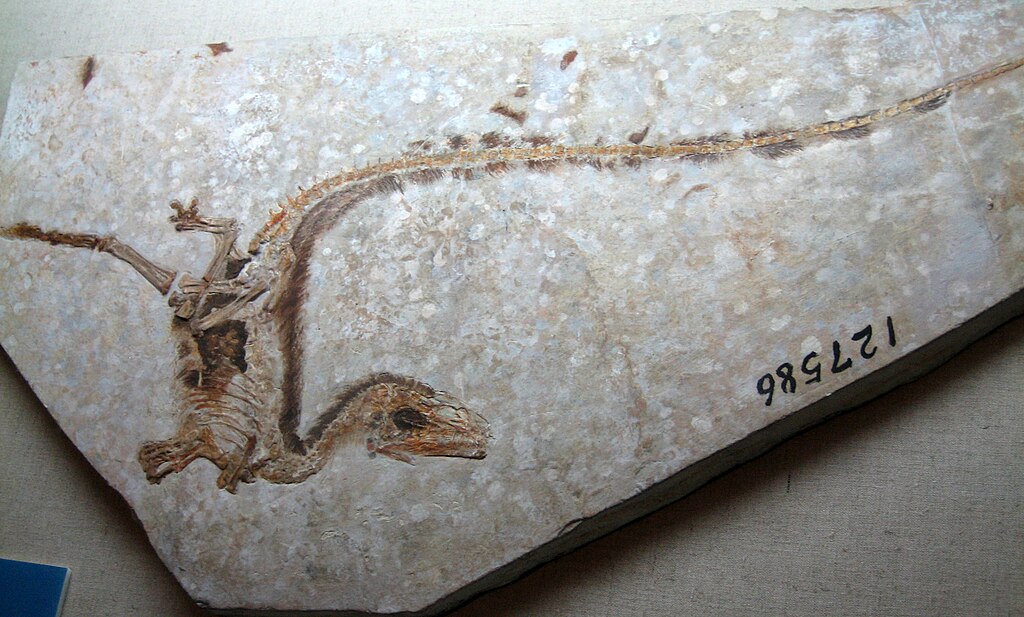

Feathered Dinosaurs: Redefining Dinosaur Skin

The discovery of feathered dinosaurs has fundamentally transformed our understanding of dinosaur skin and its evolution. Beginning with Sinosauropteryx in 1996, a series of extraordinarily preserved fossils from China’s Liaoning Province has revealed that many theropod dinosaurs—the group including Velociraptor and T. rex—possessed feather-like structures. These coverings ranged from simple filaments (proto-feathers) to complex, branching structures resembling modern bird feathers. The evidence now strongly suggests that feathers evolved initially for insulation or display, rather than flight, and were present in the common ancestor of many dinosaur groups. Perhaps most surprisingly, some ornithischian dinosaurs like Kulindadromeus and Psittacosaurus have been found with filamentous coverings, suggesting that feather-like structures might have been more widespread among dinosaurs than previously thought. These discoveries have blurred the once-clear distinction between “scaly” dinosaurs and birds, revealing instead a complex evolutionary continuum of skin coverings that ultimately produced the diverse feathers we see in modern birds.

Scale Patterns and Arrangements

Dinosaur skin fossils reveal remarkable diversity in scale patterns and arrangements that varied not only between species but across different body regions of individual animals. Many dinosaurs displayed a “basement scale” pattern—small, polygonal scales covering most of the body—interspersed with feature scales that were larger and more distinctive in specific areas. Skin impressions from ankylosaurs show how their armor developed from modified scales, while ceratopsian fossils reveal transitions between typical scales and the larger shield elements on their frills. Particularly interesting are the scale arrangements found in some hadrosaurs, where scales formed geometric patterns with five or six scales surrounding a slightly larger central scale, creating a distinctive “rosette” appearance. In some dinosaurs, scales changed dramatically across body regions—Edmontosaurus specimens show at least five distinct scale patterns from the head to the tail. These varied arrangements likely served multiple functions, from physical protection to species recognition to thermoregulation, highlighting the sophisticated adaptation of dinosaur skin to their ecological niches.

Color and Patterning: Breaking the Gray Mold

Contrary to the monochromatic gray or green dinosaurs often depicted in older reconstructions, recent scientific breakthroughs have revealed that dinosaurs displayed a rich variety of colors and patterns. By examining fossilized melanosomes—microscopic structures containing pigments—researchers can now determine some dinosaur coloration with surprising precision. The small feathered dinosaur Sinosauropteryx has been shown to have had a reddish-brown striped tail, while Microraptor likely possessed iridescent black feathers similar to modern crows. Psittacosaurus specimens reveal countershading—darker coloration on top, lighter underneath—a common camouflage strategy in modern animals. Some dinosaurs likely featured bold patterns for display or species recognition, similar to modern birds. The study of Borealopelta, an exceptionally preserved ankylosaur, revealed a reddish-brown top coloration with countershading, suggesting this heavily-armored dinosaur still relied on camouflage to avoid predation. These discoveries have transformed our visualization of dinosaurs from drab, reptilian creatures to colorful animals whose appearance likely played important roles in their behavior and ecology.

Regional Variations Across Dinosaur Bodies

Fossil evidence reveals that dinosaur skin wasn’t uniform but varied dramatically across different body regions, creating complex textural landscapes. The “mummified” Edmontosaurus specimens show at least five distinct scale patterns from head to tail, with particularly fine scales around joints to facilitate movement. In many dinosaurs, the skin along the back featured larger, more prominent scales or tubercles, sometimes forming rows that ran the length of the spine. Skin impressions from the underside of dinosaurs typically show smaller, more flexible scaling that could accommodate expansion during breathing and feeding. The tails of many dinosaurs, including hadrosaurs and some theropods, possessed distinctive scale arrangements that may have served species-recognition functions. Particularly interesting are the transitions between different skin regions, which weren’t abrupt but showed gradual blending of scale types. These regional variations reflect functional adaptations to the different physical demands placed on various body parts, from protection and display to flexibility and thermoregulation, demonstrating that dinosaur skin was as functionally complex as that of modern animals.

Skin Functionality: More Than Just Covering

Dinosaur skin served multiple crucial biological functions beyond simply covering the body. The varying scale patterns provided physical protection against environmental hazards and predators, with some regions featuring thicker, more robust scales in vulnerable areas. The textured surface created by scales likely played a significant role in thermoregulation, as the increased surface area could facilitate heat exchange with the environment—particularly important for large dinosaurs that risked overheating. In some species, especially larger ones, networks of blood vessels beneath thin-scaled areas may have acted as “radiators” to dissipate excess body heat. Skin textures also likely contributed to water conservation by reducing moisture loss in arid environments. Perhaps most overlooked is the role of skin in social and reproductive behavior—distinctive patterns and possibly colorations would have aided in species recognition, territorial displays, and mate selection. Some dinosaurs may have even used their skin for acoustic communication, as some modern reptiles produce sounds by rubbing specialized scales together. These multiple functions demonstrate that dinosaur skin was a sophisticated organ system that contributed significantly to these animals’ evolutionary success.

Modern Analogs: Birds and Reptiles

The study of modern birds and reptiles provides crucial context for interpreting dinosaur skin impressions. Since dinosaurs sit phylogenetically between these two groups—with birds actually being surviving dinosaurs—both provide valuable comparative data. Modern reptiles like crocodilians offer insights into the structure and function of the more heavily-scaled dinosaur species, particularly regarding how scales can form protective armor while maintaining flexibility. The scales on birds’ legs and feet are particularly relevant, as they represent direct descendants of dinosaur scales. Notably, the transition zones between feathered and scaled areas in modern birds help paleontologists understand similar transitions that likely existed in feathered dinosaurs. Emu and ostrich skin provides useful analogs for understanding how large, active animals manage thermoregulation through skin structures. The colorful display patterns seen in modern reptiles and birds also inform hypotheses about dinosaur coloration and its behavioral significance. By studying these living relatives, paleontologists can fill gaps in the fossil record and develop more accurate reconstructions of how dinosaur skin appeared and functioned in life.

Advanced Techniques in Studying Fossil Skin

Modern paleontology employs sophisticated technological approaches to extract maximum information from fossil skin impressions. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) allows scientists to examine skin textures at the microscopic level, revealing details invisible to the naked eye, such as the boundaries between individual scales and growth patterns. Laser-stimulated fluorescence (LSF) techniques can highlight organic residues not visible under normal light, sometimes revealing skin impressions previously undetected in fossils. Chemical analysis methods, including synchrotron rapid scanning X-ray fluorescence (SRS-XRF), can detect trace elements that indicate the presence of original pigments or other biochemical compounds in preserved skin. Three-dimensional photogrammetry creates detailed digital models of skin impressions, allowing researchers to study texture patterns without risking damage to fragile fossils. Perhaps most revolutionary has been the analysis of preserved melanosomes—microscopic structures containing pigment—which has enabled scientists to determine actual coloration in some dinosaur species. These cutting-edge approaches continue to yield new insights from both newly discovered and previously studied specimens, revolutionizing our understanding of dinosaur appearance.

Future Directions in Dinosaur Skin Research

The field of dinosaur skin research stands at an exciting frontier, with several promising directions for future discovery. Researchers are developing increasingly sophisticated techniques to identify and analyze chemical traces of original skin components, potentially revealing new information about coloration and structure. Expanded global sampling represents another important direction, as most well-preserved skin impressions come from North America and China; discoveries from other regions could reveal geographic variations in dinosaur skin adaptations. The application of machine learning algorithms to analyze scale patterns may help identify species-specific characteristics currently overlooked by human observers. Interdisciplinary collaboration with experts in modern animal dermatology promises to improve interpretations of skin function and evolution. Perhaps most tantalizing is the continued search for new “exceptional preservation” sites around the world—locations with geological conditions conducive to preserving soft tissues. Each new discovery has the potential to dramatically reshape our understanding, as demonstrated by the revolutionary impact of feathered dinosaur discoveries over the past three decades. As methods advance and new specimens emerge, our picture of dinosaur skin will continue to become more detailed and accurate.

Conclusion

The study of dinosaur skin has evolved from speculative artistry to rigorous science, fundamentally transforming our vision of these ancient creatures. Far from the uniform, gray-green reptiles of old museum displays, we now understand dinosaurs possessed diverse skin coverings ranging from complex scale patterns to colorful feathers. These coverings varied across body regions and between species, serving multiple biological functions from protection and thermoregulation to species recognition and display. While skin impressions remain rare treasures in the fossil record, each new discovery continues to refine our understanding. As technology advances and new specimens emerge, the textured landscape of dinosaur skin will continue to reveal insights about these remarkable animals’ biology, behavior, and evolution. Through these fossil impressions, we touch—quite literally—the surface of the ancient world.