You’ve probably heard the old tale. Tiny, terrified mammals cowering in the shadows while dinosaurs stomped around like they owned the planet. For over 160 million years, we’re told, our ancestors were nothing but insignificant furballs hiding from the mighty reptiles. Then an asteroid struck and boom, mammals finally got their chance.

Sounds dramatic, right? Here’s the thing though. Recent fossil discoveries have blown that simple story wide open. The truth is far stranger and more fascinating than we ever imagined. So let’s dive in.

Both Groups Started at the Same Time

Contrary to what many assume, mammals and dinosaurs trace their origins to the same time and place: around 225 million years ago, during the Triassic period when Earth’s continents were still jammed together in the supercontinent Pangea. The earliest known members of the mammal family date back to about 225 million years ago, when dinosaurs themselves were newcomers on the evolutionary stage.

This wasn’t some paradise, mind you. The planet was recovering from the worst mass extinction in history, when mega volcanoes in Siberia spewed lava and carbon dioxide for millions of years, causing a global heat spike that killed up to 95 percent of all species. Both groups emerged from this hellscape, but the archosaurs – the ancestors of dinosaurs and crocodiles – quickly seized the top spots in the food chain. Mammals took a different path entirely.

The Nocturnal Strategy Was Key

Placental mammals were mainly or even exclusively nocturnal through most of their evolutionary history, from their origin 225 million years ago during the Late Triassic to after the extinction event 66 million years ago. This wasn’t just a lifestyle choice. It was a survival mechanism.

Nocturnality may have allowed mammals to avoid antagonistic interactions with diurnal dinosaurs during the Mesozoic, essentially creating a temporal partition where both groups could coexist without stepping on each other’s toes. Many early mammals were nocturnal, a strategy that helped them avoid encounters with large, diurnal dinosaurs, opening feeding opportunities on insects and other small invertebrates. The darkness became their domain, their refuge, and ultimately their advantage.

They Were Far More Diverse Than We Thought

Let’s be real here. The old stereotype of tiny, boring insect-eaters doesn’t hold up anymore. Ancient mammals evolved a wide variety of adaptations allowing them to exploit the skies, rivers and underground lairs. We’re talking about gliders, swimmers, burrowers, and yes, even dinosaur hunters.

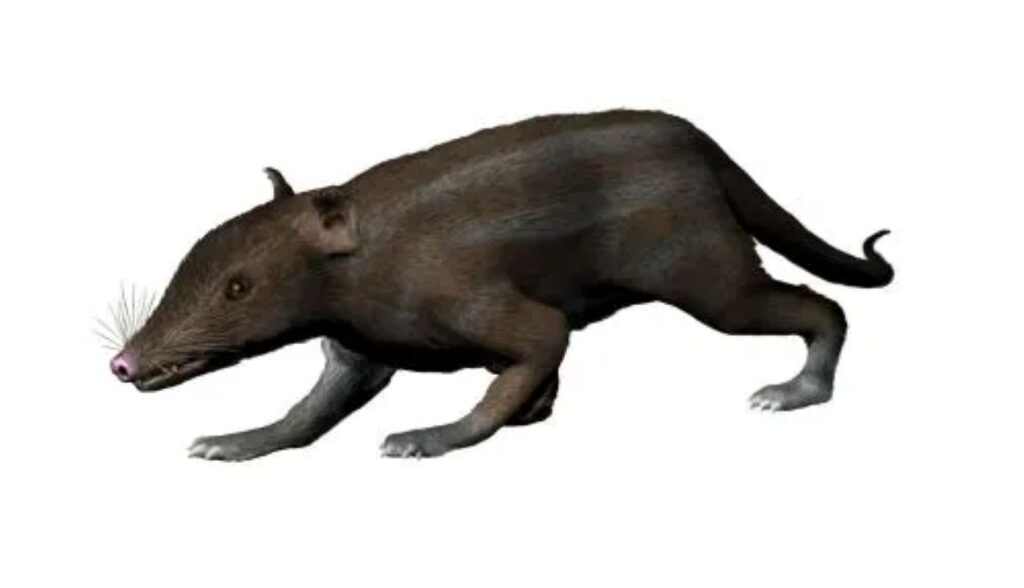

Repenomamus, a eutriconodont from the early Cretaceous 130 million years ago, was a stocky, badger-like predator that sometimes preyed on young dinosaurs, with one species more than 1 meter long and weighing about 12-14 kilograms. The Jurassic radiation included the semi-aquatic, beaver-like Castorocauda; Maiopatagium, which likely resembled today’s flying squirrels; and the tree-climbing Henkelotherium. These weren’t scared little creatures. They were thriving.

Competition Came From Other Mammals, Not Dinosaurs

Here’s where things get really interesting. Results suggest that it may not have been the dinosaurs that were placing the biggest constraints on the ancestors of modern mammals, but their closest relatives. Recent research using sophisticated statistical methods turned the old narrative completely upside down.

There were lots of exciting types of mammals in the time of dinosaurs that included gliding, swimming and burrowing species, but none belonged to modern groups; these other kinds of mammals mostly became extinct at the same time as the non-avian dinosaurs, at which point modern mammals start to become larger, explore new diets and ways of life through competition. Essentially, earlier mammal groups were hogging all the cool ecological niches, keeping modern mammal ancestors small and generalized.

Three Major Evolutionary Radiations Occurred During Dinosaur Times

The oldest mammaliaform ecological radiation ran from 190 to 163 million years ago in the early-to-mid Jurassic Period, right in the middle of dinosaur dominance. This wasn’t a fluke. A second ecological radiation of mammals began 90 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous Period, shortly after flowering plants evolved, and ended at the mass extinction event 66 million years ago.

Each time, mammals diversified from relatively simple ancestors into wildly different forms. In each radiation, mammaliaforms diversified from insect-chomping, rodent-like ancestors and adapted to a variety of ecological niches, with new species that could climb, glide or burrow and ate more specialized diets of meat, leaves or shellfish. They weren’t waiting for dinosaurs to die. They were already experimenting with different lifestyles.

Special Adaptations Made All the Difference

A very important change early on, and one which defines being a mammal, was developing teeth which occlude, or fit together to slice food efficiently. This gave mammals incredible dietary flexibility that dinosaurs simply didn’t have. While dinosaurs had one basic tooth type throughout their mouths, mammals could chew, grind, and process diverse foods.

With the miniaturization of body size, the evolution of endothermy, and the associated increase in body temperature, Mesozoic archaic mammals became obligatorily nocturnal in order to avoid poor sperm quality, hyperthermia, and high rates of evaporative water loss and to maximize foraging time. Their warm-blooded metabolism, combined with fur and the ability to regulate body temperature, allowed them to stay active when the cold-blooded dinosaurs couldn’t.

Small Size and Burrowing Saved Them When the Asteroid Hit

When that six-mile-wide asteroid slammed into what’s now Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula 66 million years ago, roughly three-quarters of all species vanished. Only 7 percent of mammals survived the carnage. So how did any make it?

Underground burrows and aquatic environments protected small mammals from the brief but drastic rise in temperature caused by the huge amount of thermal heat released by the meteor strike. Mammals could eat insects and aquatic plants, which were relatively abundant after the meteor strike, while herbivorous dinosaurs had nothing to consume once the planet’s vegetation was incinerated. Size mattered too, in ways you’d never expect.

They Exploded in Diversity Almost Immediately After

Around 100,000 years post-asteroid, a new eutherian appeared in Montana and swiftly became common: Purgatorius, with gentle molar cusps for eating fruits and highly mobile ankles for clinging and climbing in the trees, was an early member of the primate line and perhaps our ancestor. That’s right – your distant relatives were scurrying around less than 100,000 years after the dinosaurs disappeared.

In the first 10 million years following the mass extinction event, mammals bulked up, rather than evolving bigger brains, to adapt to the dramatic changes in the world around them. They weren’t smarter than the dinosaurs. They were just adaptable, flexible, and already equipped with the right toolkit. The extinction didn’t create mammalian success – it simply removed the competition that had been holding back their expansion for millions of years.

Did you expect that mammals were competing more with each other than with dinosaurs all along? The story of survival isn’t always about defeating the biggest threat. Sometimes it’s about outlasting everyone else in ways nobody saw coming.