Picture this: a colossal Argentinosaurus, weighing as much as twelve elephants, casually strolling from what we now call Argentina to Madagascar without ever getting its feet wet. Sound impossible? Welcome to the Mesozoic Era, when our planet looked nothing like the fragmented jigsaw puzzle we see today. For over 165 million years, dinosaurs ruled a world where continents were either fused together or separated by narrow seaways that could be crossed with relative ease. This wasn’t just a different world—it was a completely unified stage where these magnificent creatures could roam freely across vast distances, creating migration patterns and ecosystems that would make today’s wildlife corridors look like backyard gardens.

When Continents Kissed: The Supercontinent Reality

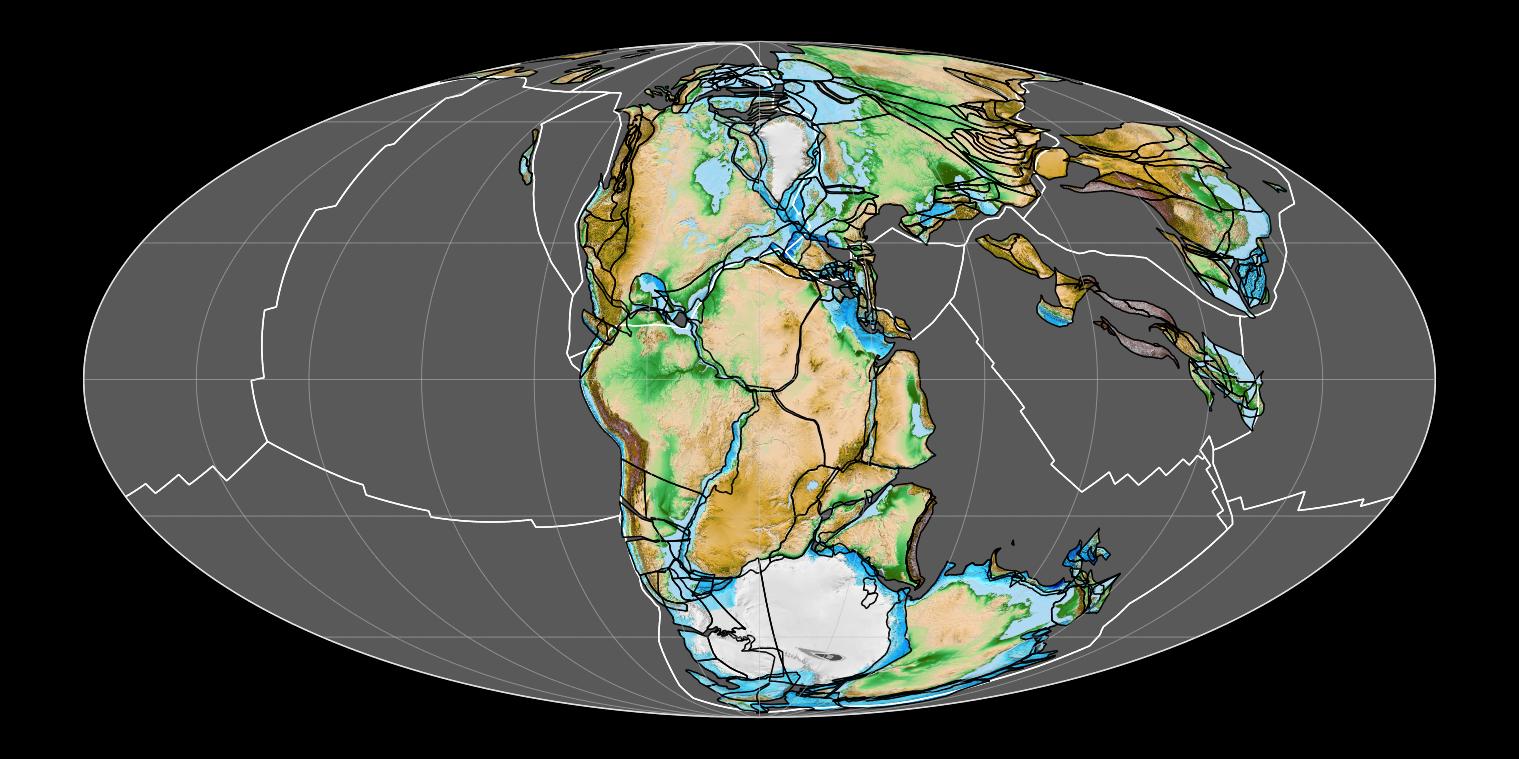

The early dinosaurs didn’t need passports or worry about oceanic barriers. They lived during the twilight years of Pangaea, the last supercontinent that had most of Earth’s landmasses squeezed together like pieces of a cosmic puzzle. When the first dinosaurs emerged around 230 million years ago, they could theoretically walk from the South Pole to the North Pole without swimming a stroke.

This geological reality shaped everything about how dinosaurs spread across the globe. The breakup of Pangaea was a slow-motion dance that took tens of millions of years, creating temporary land bridges and narrow waterways that served as highways for dinosaur migration. Think of it like a giant continent slowly cracking apart, but the cracks took longer to widen than entire dinosaur lineages existed.

The Great Rift: When Pangaea Started Breaking Apart

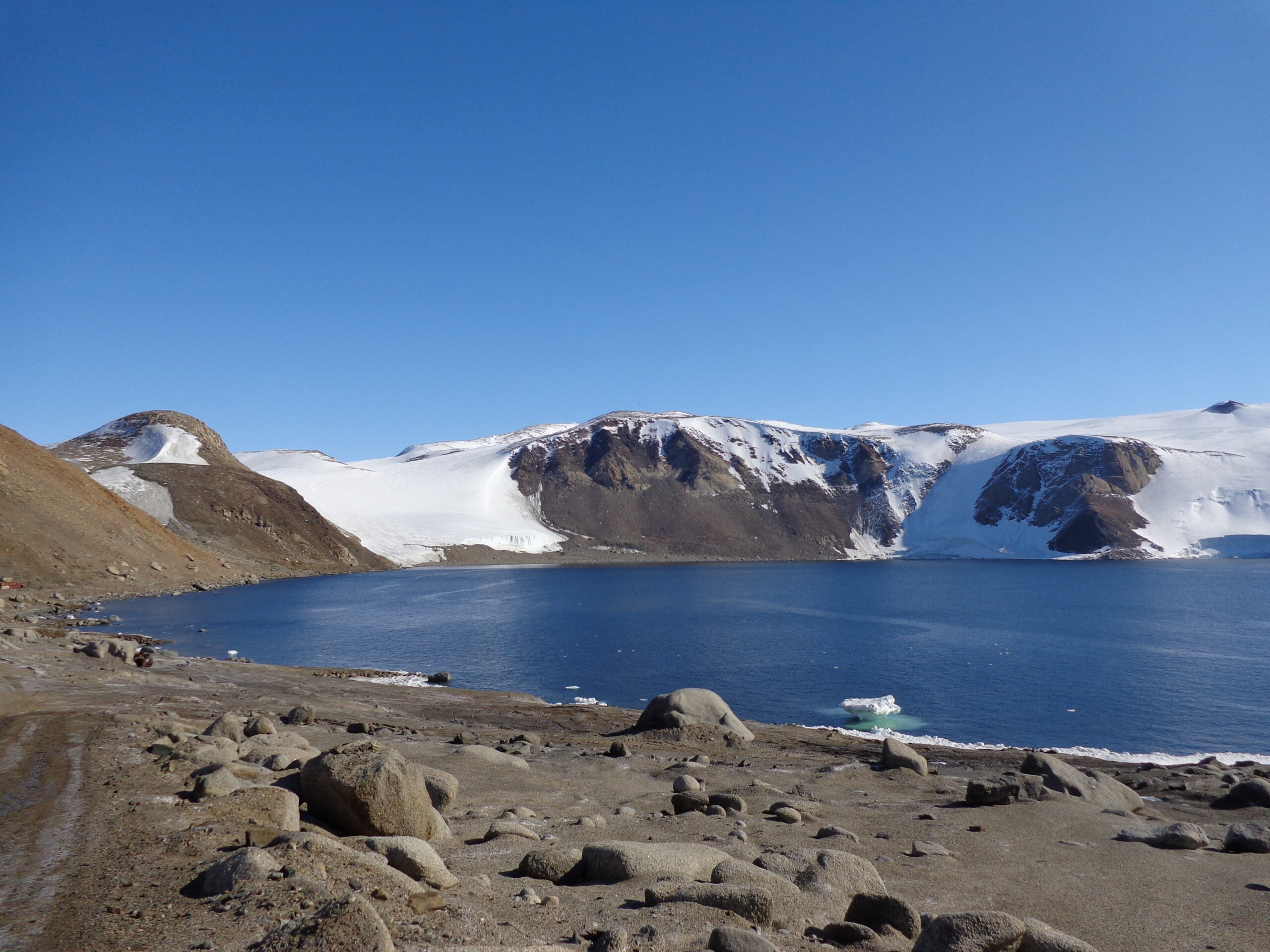

Around 200 million years ago, Pangaea began its dramatic breakup, but this wasn’t an overnight event. The supercontinent split into two major pieces: Laurasia in the north and Gondwana in the south, separated by the expanding Tethys Sea. However, these weren’t isolated landmasses—they remained connected by narrow strips of land and island chains that dinosaurs could navigate.

The rift created new opportunities and challenges for dinosaur populations. Some species found themselves suddenly living in different climatic zones as the continents drifted apart. Others discovered new ecological niches as volcanic activity and changing sea levels reshaped their world. This gradual separation explains why we find similar dinosaur fossils on continents that are now thousands of miles apart.

Highway Systems of the Mesozoic

Dinosaurs didn’t just wander aimlessly across this united Earth—they followed specific routes that paleontologists now recognize as prehistoric highways. These pathways were determined by geography, climate, and food availability. River valleys, coastal plains, and mountain passes became the Interstate system of the dinosaur world.

The most famous of these routes connected the northern and southern hemispheres through what is now the Middle East and Eastern Europe. Fossil evidence shows that sauropods regularly traveled these corridors, following seasonal patterns that brought them to different feeding grounds. These weren’t casual strolls—they were epic migrations that could span thousands of miles and take entire generations to complete.

Climate Corridors: Following the Weather

The Mesozoic climate was remarkably different from today’s world, with no ice caps and much warmer temperatures overall. This created vast climate corridors that dinosaurs could follow as seasons changed. Unlike modern animals that migrate north and south, dinosaurs often moved east and west, following bands of similar climate across the connected continents.

Temperature gradients were gentler, and seasonal changes were less extreme, making long-distance travel more feasible. A herd of Diplodocus could spend winter in what is now Morocco and summer in present-day Germany, following familiar weather patterns across a landscape that remained hospitable year-round. These climate highways were like moving walkways for dinosaur populations, facilitating gene flow and preventing isolation.

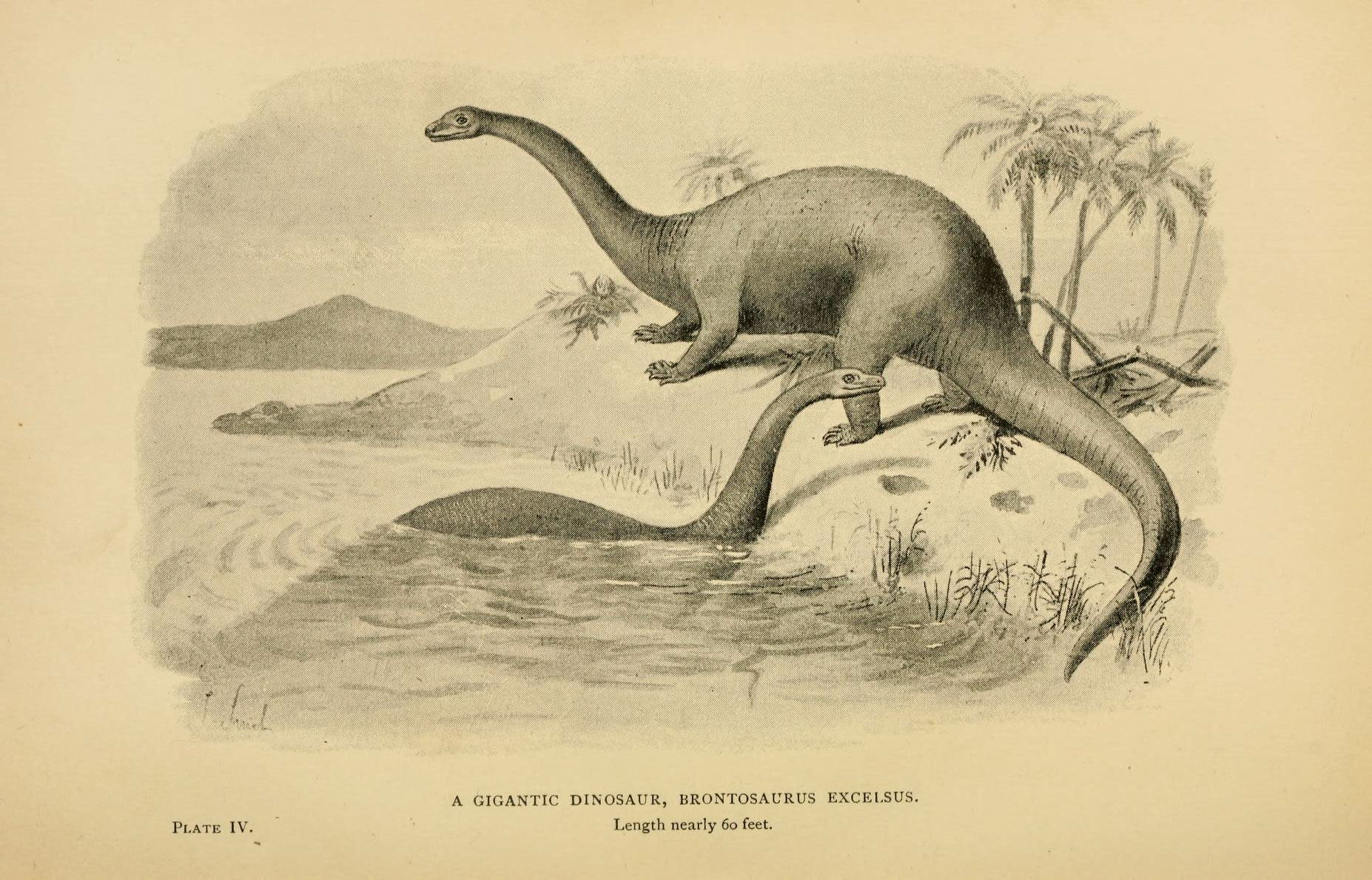

The Sauropod Superhighways

No dinosaurs were better equipped for long-distance travel than the sauropods—those long-necked giants that dominated the landscape for over 100 million years. Their massive size and efficient locomotion made them the trucks of the dinosaur world, capable of covering vast distances while carrying enormous body weights.

Sauropod trackways found in locations as diverse as Portugal, Morocco, and the American Southwest show remarkably similar patterns, suggesting these animals followed established routes across the connected continents. Their sheer size meant they could ford rivers, cross marshlands, and navigate terrain that would stop smaller dinosaurs. These gentle giants were the pioneers of intercontinental travel, creating paths that other dinosaurs would follow for millions of years.

Island Hopping in the Tethys Sea

As Pangaea continued to break apart, the expanding Tethys Sea created a complex archipelago of islands and shallow seas. Rather than being a barrier, this became a stepping-stone system that dinosaurs could navigate. Fossil evidence suggests that even large dinosaurs could island-hop across relatively short water gaps, either by swimming or walking across exposed land bridges during low sea levels.

The Tethys archipelago was like a prehistoric Mediterranean, with countless islands providing rest stops and feeding grounds for traveling dinosaurs. Some species may have even developed semi-aquatic lifestyles, spending part of their lives on islands and part in coastal waters. This island-hopping ability explains how dinosaur populations remained connected even as continents drifted apart.

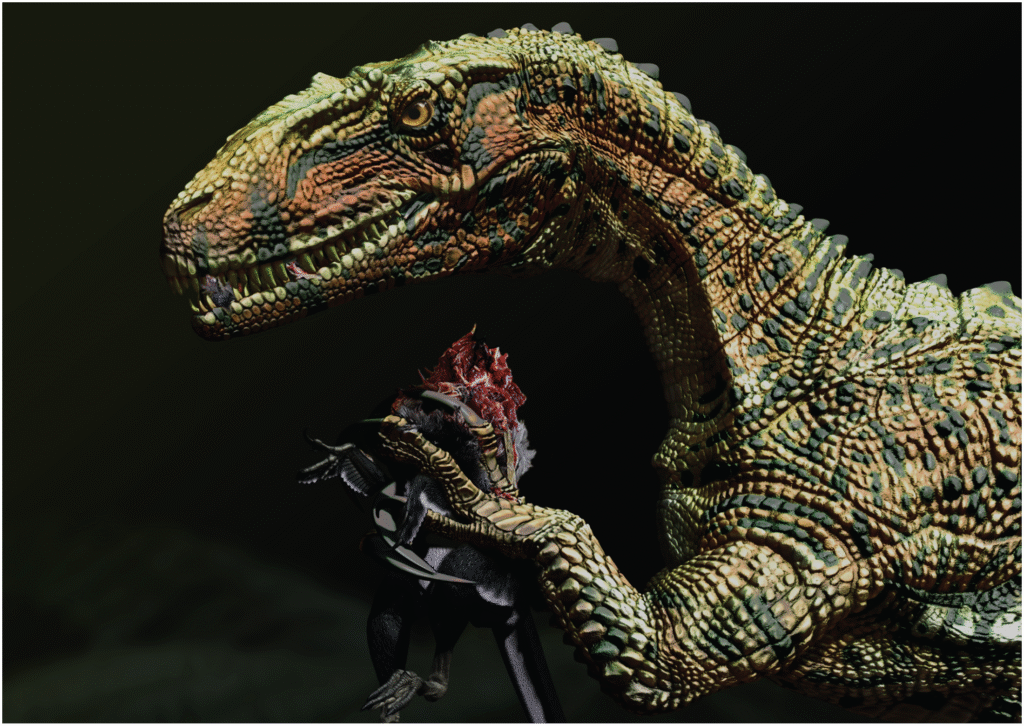

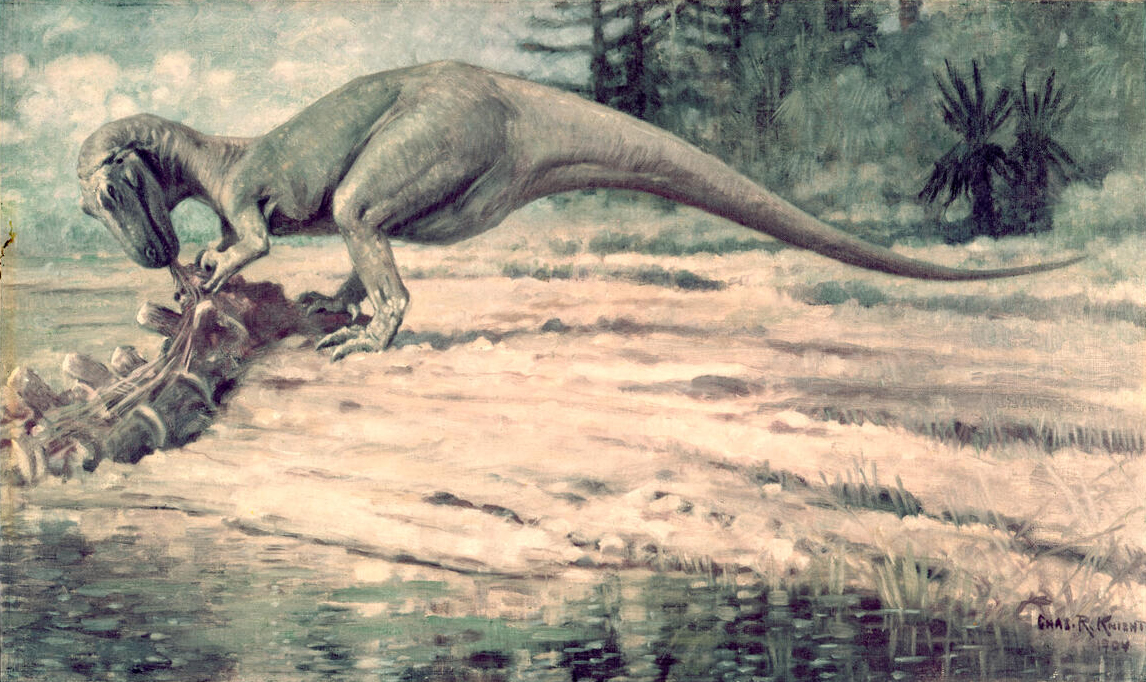

The Carnivore Express: Predator Migration Patterns

Where plant-eaters went, predators followed, creating a complex web of migration patterns that crisscrossed the united Earth. Large theropods like Allosaurus and later Tyrannosaurus relatives didn’t just hunt in one location—they followed the herds across vast distances, creating predator-prey relationships that spanned continents.

These carnivorous migrations were different from herbivore movements. Predators moved in smaller groups, followed different routes, and often took advantage of seasonal concentrations of prey animals. A pack of Utahraptor might follow a sauropod herd from Europe to Africa, picking off the weak and young during the journey. This created a dynamic ecosystem where predator and prey were locked in an eternal dance across the connected world.

Mountain Passes and Valley Routes

The geography of the united Earth created natural highways through mountain passes and river valleys that dinosaurs used for millions of years. The Central Pangaean Mountains, which ran through the heart of the supercontinent, had specific passes that became major migration routes. These weren’t just convenient pathways—they were evolutionary highways that shaped the development of dinosaur species.

Valley systems created by ancient rivers provided year-round water sources and diverse plant communities that could support large dinosaur populations during migration. The Western Interior Seaway, which later divided North America, began as a series of river valleys that dinosaurs followed from the Arctic to the Gulf Coast. These natural corridors were like prehistoric Interstate highways, complete with rest stops and feeding stations.

The Role of Sea Level Changes

Sea levels during the Mesozoic Era fluctuated dramatically, creating temporary land bridges and closing others. These changes happened on timescales that dinosaurs could adapt to, sometimes within a single generation. When sea levels dropped, new migration routes opened up; when they rose, dinosaur populations found alternative paths or became temporarily isolated.

These sea level changes were like traffic lights for dinosaur migration, directing the flow of animals across the united Earth. During low sea level periods, dinosaurs could walk across areas that are now deep ocean. During high sea level periods, they concentrated along coastal routes or used island chains as stepping stones. This dynamic system kept dinosaur populations connected while also creating opportunities for new species to evolve in temporary isolation.

Fossil Highways: Reading the Evidence

Modern paleontologists can trace these ancient migration routes through fossil evidence scattered across multiple continents. Trackways in Morocco match footprints in Connecticut, while bone beds in Argentina contain the same species found in Madagascar. These fossil highways tell the story of a connected world where dinosaurs moved freely across vast distances.

The most convincing evidence comes from juvenile dinosaur fossils found thousands of miles from where adults of the same species lived. This suggests that young dinosaurs were born in nursery areas and then traveled to adult feeding grounds, creating age-segregated migration patterns that spanned continents. These fossil highways are like ancient roadmaps, showing us exactly how dinosaurs navigated their united world.

Communication Across Continents

Long-distance migration requires communication, and dinosaurs developed sophisticated ways to stay in touch across vast distances. Hadrosaurs, with their elaborate crests and trumpeting calls, could communicate across miles of open terrain. Sauropods may have used infrasonic calls—sounds too low for humans to hear—that could travel hundreds of miles through the ground.

These communication networks were like prehistoric cell phone towers, allowing dinosaur groups to coordinate their movements across continents. A herd in Morocco could signal to relatives in Spain, coordinating seasonal movements and sharing information about food sources or dangers. This acoustic landscape was part of what made long-distance migration possible in the dinosaur world.

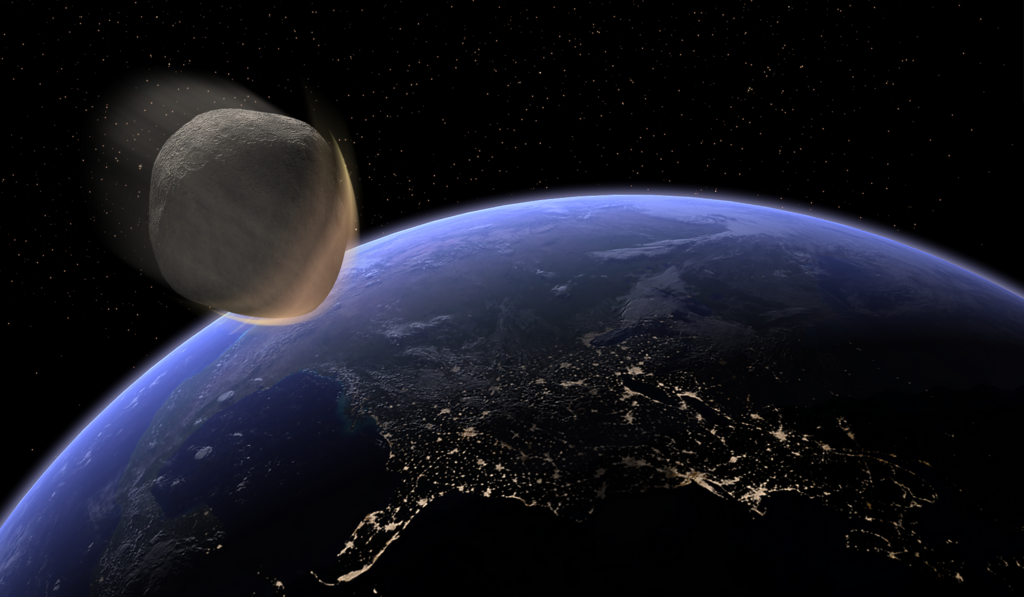

The End of an Era: Continental Drift and Isolation

As the Mesozoic Era progressed, the continents continued to drift apart, gradually closing the highways that dinosaurs had used for millions of years. By the Late Cretaceous period, around 70 million years ago, the world was becoming more fragmented, with widening oceans separating dinosaur populations that had once moved freely between continents.

This increasing isolation had profound effects on dinosaur evolution. Species that had once been connected across continents began to evolve in different directions, creating the regional differences we see in Late Cretaceous dinosaur faunas. The united Earth was becoming the fragmented world we know today, and dinosaurs were forced to adapt to smaller, more isolated territories.

Legacy of a Connected World

The dinosaurs’ experience of a united Earth left lasting impacts that we can still see today. Their migration routes influenced the distribution of modern ecosystems, and their movements helped spread plant species across continents. The paths they carved through mountains and valleys became the foundation for modern river systems and wildlife corridors.

Understanding how dinosaurs navigated their connected world also provides insights into how modern animals might adapt to climate change and habitat fragmentation. The dinosaur world shows us what’s possible when barriers are removed and animals can move freely across vast distances. Their 165-million-year success story demonstrates the power of connectivity in maintaining healthy, diverse ecosystems.

The world beneath their feet was vastly different from our own—a connected, dynamic landscape where giants roamed freely across continents that are now separated by vast oceans. These ancient highways carried more than just dinosaurs; they carried the seeds of evolution, the patterns of climate, and the blueprint for life on a united Earth. Did you ever imagine that the ground you walk on once supported the footsteps of creatures traveling between continents that are now thousands of miles apart?