Picture yourself walking through ancient forests and grasslands where massive, fearsome predators once ruled the earth. The last of these incredible creatures vanished less than 10,000 years ago, leaving behind only fossils and our endless fascination. These weren’t your average big cats.

Although commonly known as the saber-toothed tiger, it was not closely related to the tiger or other modern cats, belonging to an entirely different evolutionary lineage. You’ll discover that everything you thought you knew about these prehistoric hunters might surprise you. From their shocking social behaviors to their mysterious extinction, these ancient predators continue to reveal secrets that challenge our understanding of Ice Age life.

So let’s dive into the most captivating about these legendary creatures.

They Weren’t Actually Tigers at All

You might be shocked to learn that calling them “saber-toothed tigers” is completely misleading. Despite the colloquial name, Smilodon was not closely related to the tiger or any other modern cats, with ancestors estimated to have diverged around 20 million years ago. Think of it like calling a whale a fish because they both live in water.

These cats belonged to a separate lineage called Machairodontinae that diverged early from the ancestors of living cats. Modern tigers belong to the Pantherinae subfamily, making them about as related to saber-toothed cats as you are to your distant cousin from centuries ago. This is why a more acceptable generic name for Smilodon is “saber-toothed cat” rather than tiger.

Their Teeth Were Absolutely Massive

Smilodon is most famous for its relatively long canine teeth, which are the longest found in the saber-toothed cats, at about 15-17 cm (6-7 inches) long in the largest species. Imagine carrying around two knives in your mouth that are nearly a foot long each. The canines were slender and had fine serrations on the front and back side, making them perfect slicing weapons.

These weren’t just for show either. The immense upper canine teeth were probably used for stabbing and slashing attacks, possibly on large herbivores such as the mastodon. However, those impressive fangs came with a serious downside. Analysis indicates they could produce a bite only a third as strong as that of a lion, proving that sometimes bigger isn’t always better.

They Could Open Their Jaws Impossibly Wide

Smilodon’s jaw could open to about a 90° angle, with some estimates reaching up to 120 degrees compared to around 65 degrees for modern large cats. Picture trying to fit a basketball in your mouth, and you’ll get an idea of how incredible this adaptation was. This massive gape was absolutely necessary for their hunting strategy.

The enormous gape was necessary for food items to get past the long canine teeth, allowing them to position their sabers for the killing blow. The protruding incisors were arranged in an arch and were used to hold the prey still and stabilize it while the canine bite was delivered. Without this incredible jaw flexibility, their massive teeth would have been useless weapons.

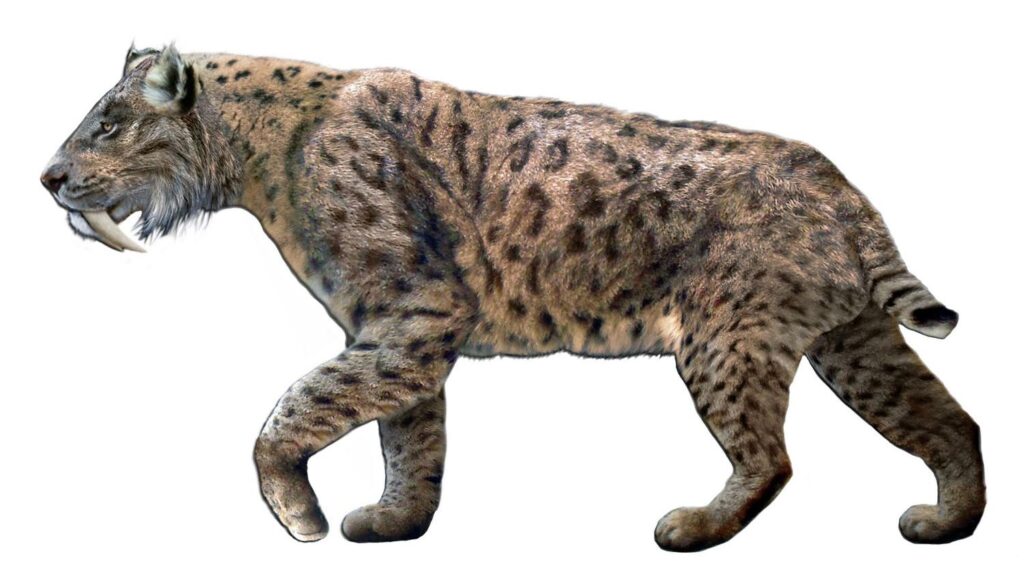

They Were Built Like Tanks

Smilodon was around the size of modern big cats but was more robustly built, with a reduced lumbar region, high scapula, short tail, and broad limbs with relatively short feet. The largest species could reach up to approximately 220-400 kilograms (485-880 lb) with a shoulder height about the same as a lion or tiger’s. They were basically the bodybuilders of the cat world.

Their limbs were shorter and thicker than other felines, with powerful abductor muscles and denser bones. This wasn’t about looking intimidating. These physical adaptations gave them more stability and power when wrestling with their prey, making them incredibly effective at taking down massive Ice Age megafauna that would dwarf modern elephants.

They Were Ambush Predators, Not Sprinters

These physical adaptations suggest that saber-toothed tigers were ambush hunters that stalked their prey, supported by evidence from their head structure and teeth. Unlike modern cats with long tails for stability during chases, Saber tooth tigers had a bobtail, suggesting they would have hidden and waited for their prey. Think patient spider rather than racing cheetah.

Instead of chasing prey, saber-toothed cats were ambush predators who stalked their prey while hiding in tall grasslands, then pounced and inflicted deep wounds with their teeth before waiting for the prey to bleed to death. This hunting style perfectly matched their muscular build and massive weapons, making them devastatingly effective killers when they struck.

They Likely Lived in Social Groups

This might be the most surprising fact of all. Unlike modern cats which are solitary hunters, the saber tooth tiger was a social animal thought to have lived in packs with a social structure much like lions do. The evidence for this claim is absolutely fascinating and comes from studying their injuries.

Fossils from La Brea tar pits show proof that some animals had experienced severe injuries including fractures and arthritis, yet showed extensive healing and regrowth, suggesting they survived after injuries and were most likely cared for by other cats who enabled them to feed. One individual with hip dysplasia from birth survived to adulthood, which would have been impossible without family support since it could never have hunted or defended territory on its own.

They Hunted Massive Prehistoric Beasts

Isotopes preserved in bones reveal that ruminants like bison (which was much larger than the modern American bison) and camels were most commonly taken by the cats. The size of their teeth and robustness of their skeleton suggest their prey included large mammals like bison, horses, camels, giant ground sloths, and probably young mammoths and mastodonts. These weren’t house cats hunting mice.

They mostly hunted large prey that moved slowly, with the elephantlike mastodon probably being their usual meal, along with mammoths and bison. Evidence shows they could even occasionally prey upon armored Glyptotherium, successfully biting through the glyptodont’s armored cephalic shield. Their specialized hunting equipment was perfectly designed for taking down giants.

They Lived Across the Americas for Millions of Years

Smilodon lived in North and South America, with fossil evidence dating back around 1.8 million years ago, and a similar but smaller species existing 2.5 million years ago. They were extremely widespread, found on several continents including North America, South America, and Europe, living from the Miocene to the Pleistocene epochs and roaming diverse habitats including forests, grasslands, and deserts.

Fossils have been found throughout the Americas, with the northernmost remains found in Alberta, Canada, and the southernmost in Patagonia near the Strait of Magellan. For millions of years, these incredible predators dominated their ecosystems from the frozen north to the southern tip of South America.

Their Extinction Remains a Scientific Mystery

Scientists have uncovered enough to formulate ideas about how they passed from the world 10,000 years ago, but each theory has its challengers. The extinction remains “the million-dollar question” according to researchers. Was it climate change, human competition, or something else entirely?

The Smilodon went extinct during the Quaternary extinction event when fifteen kinds of large mammals went extinct in North America during a 1,500-year window, compared to only 33 total extinctions during the past 50,000 years. It’s probably most likely that a combination of human hunting and climate change contributed to their extinction, though evidence on whether humans lived alongside these cats is still uncertain.

They Left Behind an Incredible Fossil Legacy

Smilodon californicus is the second most common mammal fossil found in the famous Rancho La Brea tar pits in Los Angeles. With 13,000 specimens from some 2,000 individuals recovered, Smilodon is one of the most abundant fossils in La Brea tar pits, second only to the dire wolf. These natural traps created an incredible window into their world.

One of the most famous of prehistoric mammals, Smilodon has often been featured in popular media and is the state fossil of California. The first species was discovered in Brazil in 1830, followed by North American discoveries in 1869, and the third species in 1880. Their fossils continue to reveal new secrets about these magnificent predators, helping us understand one of evolution’s most successful and specialized hunters.

Conclusion

These remarkable predators were far more complex and fascinating than most people realize. From their surprising social behaviors to their incredibly specialized hunting adaptations, saber-toothed cats represent one of evolution’s most successful experiments in predatory design. The Saber-toothed Cats continue to captivate our collective imagination and provide essential insights into the ecological dynamics of the past.

Their story reminds us how quickly even the most successful species can vanish when their world changes too rapidly. What do you think about these incredible Ice Age hunters? Tell us in the comments.