The Mesozoic Era, often called the “Age of Dinosaurs,” spans an immense 186 million years of Earth’s history. Divided into three distinct periods—the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous—this era witnessed dramatic transformations in Earth’s climate, geography, and most notably, its inhabitants. While dinosaurs dominate our popular imagination of this time, the transitions between these periods represent profound evolutionary turning points and environmental shifts that shaped life as we know it today. Each period had its unique character, with different dominant species, climate conditions, and geological features. Let’s explore what truly changed as Earth moved through these fascinating chapters of prehistoric time.

The Mesozoic Timeline: Setting the Stage

The Mesozoic Era began approximately 252 million years ago following the devastating Permian-Triassic extinction event, which eliminated about 95% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrates. This era continued until about 66 million years ago, ending with another mass extinction that famously wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs. The Triassic period lasted from 252 to 201 million years ago, followed by the Jurassic period from 201 to 145 million years ago, and finally the Cretaceous period from 145 to 66 million years ago. These dates weren’t arbitrary divisions but rather marked by significant extinction events and changes in the fossil record. Understanding this timeline helps contextualize the massive transformations that occurred as life recovered, diversified, and evolved through these three distinct chapters of Earth’s history.

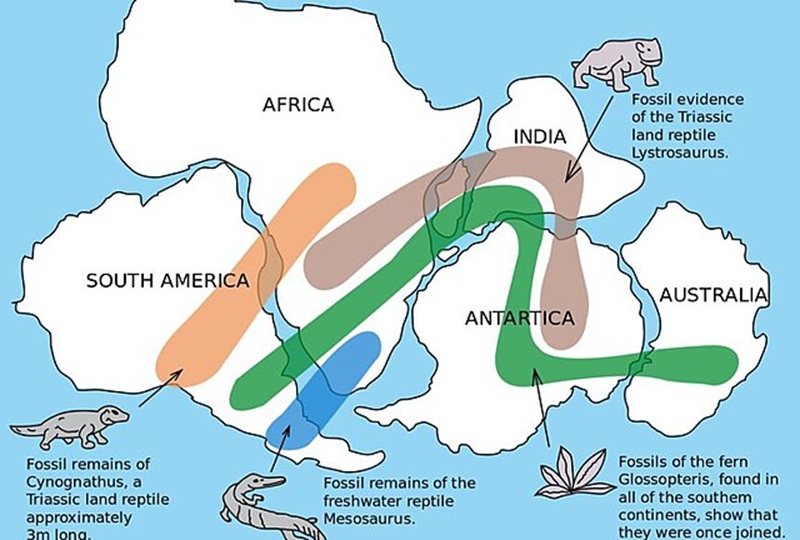

Pangaea’s Breakup: Reshaping Earth’s Geography

One of the most significant changes across these three periods was the gradual breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea, which fundamentally altered global geography. During the early Triassic, nearly all landmasses were fused together in this single massive continent surrounded by the vast Panthalassa Ocean. By the mid-Triassic, rifting began as Pangaea started to split into Laurasia in the north and Gondwana in the south, separated by the developing Tethys Sea. The Jurassic period witnessed continued fragmentation as the Atlantic Ocean began forming between what would become North America and Africa. By the Cretaceous period, continents were approaching their modern configurations, with India still separated as an island continent moving northward, and Australia-Antarctica beginning to separate from Africa and South America. This continental drift dramatically affected ocean currents, weather patterns, and created isolated environments where evolution could proceed along different paths.

Climate Transformations: From Hot and Dry to Warm and Wet

Climate patterns shifted dramatically between these three periods, influencing the evolution and distribution of life. The Triassic period began with a hot, arid climate worldwide, partly due to Pangaea’s interior being far from moderating oceanic influences. Extreme seasonality characterized this time, with intense monsoons along coastal regions and severe droughts inland. The Early Jurassic saw a shift to generally warmer, more humid conditions globally as the breakup of Pangaea created more coastlines and maritime climates. Sea levels rose significantly during the Jurassic, creating vast shallow seas and more moderate temperatures. The Cretaceous period is known for having one of the warmest global climates in Earth’s history, with little to no polar ice and sea levels up to 200 meters higher than today. Atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were significantly higher throughout the Mesozoic than today, contributing to the greenhouse conditions that allowed dinosaurs and lush vegetation to thrive even at high latitudes.

Mass Extinction Boundaries: Nature’s Reset Buttons

The transitions between these periods were defined by significant extinction events that functionally served as evolutionary reset buttons. The Triassic began in the aftermath of the Great Dying—the Permian-Triassic extinction that eliminated most of life on Earth. The Triassic-Jurassic boundary around 201 million years ago was marked by another major extinction event that wiped out approximately 80% of species, possibly linked to massive volcanic eruptions in what is now the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province. This event eliminated most large amphibians and many marine reptiles, opening ecological niches that dinosaurs would rapidly fill. The Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary was less catastrophic but still saw significant turnover in marine life and some terrestrial groups. Finally, the Cretaceous ended with the famous Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event approximately 66 million years ago, triggered by a massive asteroid impact combined with volcanic activity, eliminating roughly 75% of all species including all non-avian dinosaurs. These extinction boundaries represent crucial turning points in evolutionary history, allowing surviving lineages to diversify into newly vacant ecological niches.

Triassic Pioneers: The First Dinosaurs Emerge

The Triassic period witnessed the humble beginnings of the dinosaur lineage, though these early forms were far from the dominant creatures they would later become. The earliest known dinosaurs appeared in the Late Triassic, around 230 million years ago, with primitive forms like Eoraptor and Herrerasaurus from South America representing some of the first members of this evolutionary line. These early dinosaurs were relatively small, bipedal creatures that shared their environments with many other reptilian groups that were actually more diverse and numerous at the time. Notably, dinosaurs coexisted with and competed against pseudosuchians (relatives of modern crocodilians), large amphibians, and various other reptile groups like the sail-backed Placerias. What made early dinosaurs special was their upright posture with legs positioned directly beneath their bodies—a more energy-efficient stance than the sprawling gait of many contemporaries. This innovation, along with other adaptations, would give dinosaurs a crucial edge after the Triassic-Jurassic extinction eliminated many competing groups.

Jurassic Giants: The Age of Sauropods

The Jurassic period saw dinosaurs truly come into their own, evolving larger sizes and greater diversity, particularly the sauropods—those iconic long-necked giants. This period witnessed the rise of some of the largest land animals to ever walk the Earth, including Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus, and Apatosaurus, some reaching lengths of over 30 meters and weights exceeding 50 tons. These massive herbivores developed specialized features to support their enormous size, including hollow bones to reduce weight, air sacs connected to their lungs for efficient breathing, and unique egg-laying strategies. The Jurassic also saw the emergence of the first birds, with Archaeopteryx appearing around 150 million years ago, representing a crucial evolutionary bridge between dinosaurs and modern birds. Medium-sized predators like Allosaurus dominated the carnivorous niches, while early stegosaurs with their distinctive back plates and spiked tails evolved as a defensive adaptation. Marine ecosystems teemed with plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and massive marine crocodilians, creating complex food webs in the expanding shallow seas.

Cretaceous Diversity: The Peak of Dinosaur Specialization

The Cretaceous period represented the pinnacle of dinosaur evolution, with unprecedented diversity and specialization across numerous ecological niches. This period introduced many of the most recognizable dinosaur groups, including Tyrannosaurus rex, Triceratops, and Velociraptor. Ceratopsians evolved elaborate frills and horns, likely used for species recognition and competition for mates. Hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) developed complex dental batteries capable of efficiently processing plant material, while ankylosaurs featured heavy body armor and club-like tails for defense. The famous Tyrannosauridae family evolved in the Late Cretaceous, with T. rex representing the apex predator of its time in North America. Perhaps most importantly, small feathered dinosaurs continued to diversify, with the ancestors of modern birds becoming increasingly specialized for flight. Dinosaur diversity reached its zenith during this period, with distinct regional faunas developing on the separated continents, demonstrating incredible evolutionary adaptability before their sudden extinction at the period’s end.

Marine Life Evolution: Changing Oceans Across Periods

The oceanic ecosystems underwent dramatic transformations across the three periods, reflecting changes in sea levels, ocean chemistry, and evolutionary pressures. Triassic seas were initially depauperate following the Permian extinction, but gradually recovered with the evolution of new groups of mollusks, particularly ammonites with their distinctive spiral shells that would become key index fossils for dating rocks. Marine reptiles like ichthyosaurs and nothosaurs (early relatives of plesiosaurs) began to dominate as top predators. The Jurassic saw an explosion of marine diversity with the evolution of more specialized plesiosaurs, pliosaurs, and highly adapted fish-like ichthyosaurs. Reef ecosystems flourished during this period, though composed of different organisms than modern reefs, with corals and sponges creating complex habitats. The Cretaceous brought even more dramatic changes as sea levels rose significantly, creating vast inland seas like the Western Interior Seaway that split North America. Massive marine reptiles reached their peak diversity, including mosasaurs—enormous marine lizards that became top predators. The first truly modern sharks appeared, and teleost fishes (the dominant fish group today) underwent substantial diversification, setting the stage for modern marine ecosystems.

Plant Life Revolutions: From Seed Ferns to Flowering Plants

Plant communities underwent revolutionary changes across the Mesozoic, fundamentally altering terrestrial ecosystems and food webs. Early Triassic landscapes were initially dominated by lycopods, horsetails, and ferns—plant groups that could quickly recolonize devastated landscapes after the Permian extinction. By the Middle Triassic, gymnosperms (non-flowering seed plants) including conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes became dominant components of most terrestrial ecosystems. The Jurassic continued this trend, with dense conifer forests covering much of the land, creating the lush vegetation needed to support massive herbivorous dinosaurs. The most dramatic botanical change occurred during the Cretaceous with the emergence and rapid diversification of angiosperms—flowering plants—starting around 125 million years ago. By the Late Cretaceous, angiosperms had become the dominant plant group in many ecosystems, triggering co-evolutionary relationships with insects and other pollinators. This angiosperm revolution dramatically increased the complexity and productivity of terrestrial ecosystems, providing new food sources and habitats that would profoundly influence animal evolution, including the dietary adaptations of many dinosaur groups like hadrosaurs and ceratopsians.

Mammal Origins: Small But Significant Changes

While dinosaurs commanded center stage, the Mesozoic witnessed the crucial early evolution of mammals from their cynodont ancestors. During the Triassic, early mammaliaforms like Morganucodon emerged, showing the first mammalian characteristics including specialized jaw joints and inner ear bones that evolved from reptilian jaw bones. These early proto-mammals were small, likely nocturnal creatures that probably fed on insects and avoided competition with the larger reptiles. The Jurassic saw the appearance of true mammals, including the earliest monotremes (egg-laying mammals), as well as primitive marsupials and placentals. These early mammals remained small, rarely exceeding the size of a modern house cat, but they were diversifying into different ecological niches. By the Cretaceous, mammals had developed most of the major lineages that would later flourish after the dinosaur extinction, including multituberculates (a now-extinct group that was highly successful), as well as the ancestors of modern marsupials and placentals. The long “shadow” period of mammalian evolution under dinosaur dominance was characterized by important adaptations including advanced thermoregulation, greater intelligence, and specialized dentition that would later prove advantageous when the ecological opportunity presented itself after the dinosaur extinction.

Atmospheric Composition: Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide Fluctuations

The Mesozoic Era experienced significant fluctuations in atmospheric composition that influenced the evolution and distribution of life. Oxygen levels during the Triassic were initially relatively low (around 15%) compared to today’s 21%, a lingering effect of the Permian extinction that had disrupted global ecosystems and carbon cycles. Carbon dioxide levels, however, were substantially higher than present-day values, creating strong greenhouse conditions. Throughout the Jurassic, oxygen levels gradually increased to closer to modern values, while CO₂ concentrations remained elevated at roughly 4-5 times current levels. The Cretaceous saw some of the highest oxygen levels of the Mesozoic, potentially reaching 30% in the Late Cretaceous according to some models, which may have supported the gigantism seen in many animals of this period. Concurrently, CO₂ concentrations fluctuated but remained high, contributing to the extremely warm climate. These atmospheric conditions had profound effects on organisms, potentially enabling the evolution of more efficient respiratory systems in dinosaurs and contributing to the rapid growth rates of vegetation that fed the massive herbivores. The higher oxygen levels may have also influenced wildfire frequency and intensity, shaping plant adaptations and ecosystem dynamics.

Evolutionary Arms Races: Predator-Prey Dynamics

The relationship between predators and prey evolved dramatically across the three periods, creating complex evolutionary arms races that drove adaptation. During the Triassic, early dinosaur predators like Coelophysis competed with dominant pseudosuchians (crocodile relatives) such as Postosuchus, while prey species had limited defensive adaptations. The Jurassic saw more sophisticated relationships develop, with predators like Allosaurus evolving powerful biting techniques and blade-like teeth, while prey species like stegosaurs developed defensive tail spikes and plates, and sauropods relied on sheer size for protection. By the Cretaceous, these dynamics had become even more specialized, with predators like Tyrannosaurus developing massive crushing bite forces that could shatter bone, while prey species evolved remarkable defensive adaptations—Triceratops with its three horns and neck frill, Ankylosaurus with its armored body and tail club, and Parasaurolophus with its keen senses and possible herding behavior. The most dramatic evolutionary arms race occurred between small predatory dinosaurs (particularly dromaeosaurs like Velociraptor) and their prey, driving the evolution of greater intelligence, improved vision, and faster running speeds on both sides. These predator-prey relationships were major drivers of evolutionary change throughout the Mesozoic, constantly pushing species to develop new adaptations to survive.

From Triassic to Cretaceous: The Evolution of Flight

The conquest of the air represents one of the most remarkable evolutionary developments across the three periods, occurring through multiple independent lineages. During the Late Triassic, pterosaurs became the first vertebrates to evolve powered flight, with early forms like Eudimorphodon having wingspans of about 1 meter and likely feeding on fish and insects. Throughout the Jurassic, pterosaurs diversified into numerous specialized forms, while a separate lineage of dinosaurs began developing feathers and proto-wings, culminating in Archaeopteryx—often considered the first bird, though it retained many dinosaurian features like teeth and a long bony tail. The Cretaceous witnessed an explosion of flying creatures, with pterosaurs reaching their peak diversity and size (Quetzalcoatlus had a wingspan of 10-11 meters, making it the largest flying animal ever known), while birds underwent rapid diversification into multiple lineages. Many non-avian dinosaurs also evolved feathers and wing-like structures without becoming fully flight-capable, suggesting these features may have initially evolved for display, insulation, or other purposes before being co-opted for flight. By the Late Cretaceous, modern-looking birds had evolved alongside the still-dominant pterosaurs, creating complex aerial ecosystems with different species specializing in various ecological niches, from fish-catching to forest gliding, demonstrating the incredible versatility of flight as an evolutionary strategy.

The Signature Fossil Record: How We Know What Changed

Our understanding of the transitions between these periods comes primarily from the fossil record, which provides distinctive signature assemblages for each time. Triassic rocks typically contain an abundance of primitive archosaurs, temnospondyl amphibians, and early synapsids, along with distinctive plant fossils like the seed fern Dicroidium.