In the shadow of Industrial Revolution smokestacks and beneath the weight of rigid social hierarchies, a remarkable scientific revolution was quietly taking place in Victorian Britain. Armed with hammers, chisels, and an insatiable curiosity about Earth’s ancient past, fossil hunters of the 19th century ventured into quarries, along coastal cliffs, and through limestone caves to unearth evidence of creatures that had vanished millions of years before. This era marked the transition of paleontology from casual curiosity to rigorous science, all against a backdrop of class struggles, gender limitations, and fierce academic rivalries. The Victorian fossil hunters didn’t just discover extinct species; they challenged religious orthodoxy, established new scientific disciplines, and in some cases, defied the social constraints of their time to leave an indelible mark on our understanding of natural history.

The Birth of Modern Paleontology

The Victorian era coincided with a critical juncture in the scientific understanding of Earth’s history, as the emerging discipline of geology was beginning to reveal the planet’s true age. Prior to this period, most Europeans believed in a young Earth created just thousands of years ago, but evidence of extinct creatures embedded in ancient rock layers suggested a much longer timeline. Pioneers like James Hutton and Charles Lyell had established principles of geological uniformitarianism that suggested Earth had undergone slow, gradual changes over immense periods. This intellectual environment proved fertile ground for fossil hunters, whose discoveries would become crucial evidence supporting theories of an ancient Earth with a succession of different life forms. The Victorian fossil hunters weren’t merely collectors of curiosities; they were assembling the pieces of a revolutionary scientific puzzle that would ultimately transform our understanding of life’s history and challenge fundamental religious beliefs about creation.

Mary Anning: The Unsung Heroine of Paleontology

On the windswept beaches of Lyme Regis, a working-class woman named Mary Anning became one of history’s most important fossil hunters despite receiving little formal education and facing severe gender discrimination. Beginning her career as a child collecting fossils to sell to tourists, Anning discovered the first complete ichthyosaur skeleton recognized by science when she was just twelve years old. Throughout her life, she uncovered numerous marine reptile fossils including the first complete plesiosaur, the first pterosaur outside Germany, and countless invertebrate specimens that helped establish the field of paleontology. Despite her extraordinary contributions, Anning was frequently denied credit for her discoveries, with male scientists often publishing her finds under their own names. The scientific societies of London refused her membership because of her gender, and she died in relative obscurity and poverty in 1847, though her discoveries had fundamentally altered scientific understanding of prehistoric life. Today, Mary Anning is rightfully recognized as one of the most influential figures in the history of paleontology, her story illustrating both the remarkable scientific advances and the profound social limitations of the Victorian era.

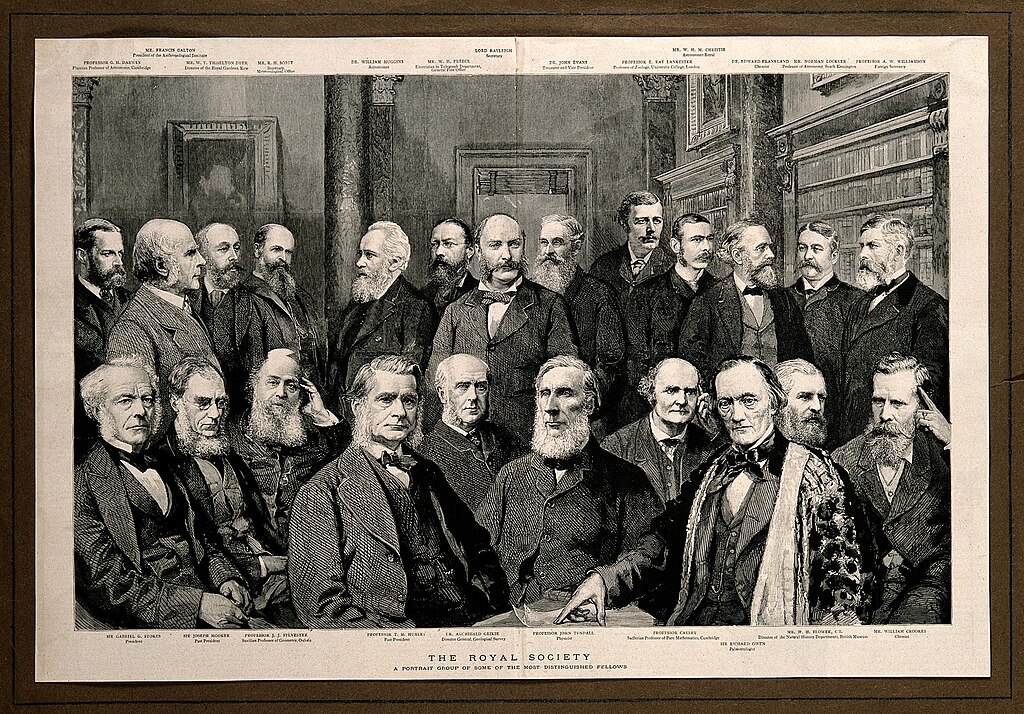

Gentlemen Scientists and Class Dynamics

Victorian paleontology reflected the rigidly stratified society in which it operated, creating distinct classes of fossil hunters with dramatically different resources and recognition. At the top of this hierarchy stood the “gentlemen scientists” – wealthy, university-educated men like Sir Richard Owen and Gideon Mantell who could pursue scientific interests without financial concerns and who dominated the prestigious scientific societies. The middle tier comprised professional collectors like Mary Anning, who possessed extraordinary expertise but lacked social standing and often struggled financially, selling their specimens to museums and wealthy collectors to survive. At the bottom were working-class fossil hunters who provided physical labor in quarries and cliff faces, frequently making important discoveries but receiving minimal compensation or acknowledgment. This class structure meant that the official scientific record often obscured the contributions of those of lower social standing, particularly women and working-class collectors. The scientific establishment’s journals, meetings, and published works primarily reflected the voices of privileged men, leaving others’ contributions to be recovered by later historians of science who recognized the collaborative nature of Victorian paleontological advances.

The Great Dinosaur Rush

The discovery of massive reptilian fossils in the early Victorian period triggered what became known as “dinosaur fever,” a competitive rush to unearth, name, and display these spectacular creatures. The term “dinosaur” itself was coined in 1842 by anatomist Richard Owen, providing a scientific classification for the increasingly numerous fossils of enormous extinct reptiles being discovered throughout Britain. Gideon Mantell’s discovery of Iguanodon teeth in 1822 and the subsequent unveiling of complete skeletons captivated both scientific circles and the general public’s imagination. As more specimens emerged, wealthy collectors and institutions engaged in fierce bidding wars for the most impressive examples, while scientists competed intensely to name new species, sometimes rushing to publication with incomplete evidence. This competitive atmosphere occasionally led to scientific fraud and exaggeration as reputations and fortunes hung in the balance. The Crystal Palace dinosaur models, unveiled in 1854, represented the culmination of this dinosaur mania, bringing full-sized representations of these prehistoric creatures to public view for the first time and cementing their place in Victorian popular culture despite being anatomically inaccurate by modern standards.

The Owen-Huxley Scientific Feud

Few scientific rivalries in Victorian Britain matched the intensity and significance of the conflict between anatomist Richard Owen and Darwin’s champion Thomas Henry Huxley. Owen, the established scientific authority who had coined the term “dinosaur,” initially enjoyed considerable prestige and power within scientific circles, using his influence at the British Museum and with the Royal Society to advance his career and sideline rivals. Huxley, younger and more progressive, challenged Owen’s scientific conclusions and ethical conduct on multiple occasions, most famously regarding human evolution and anatomical comparisons between humans and great apes. Their clashes extended beyond scientific disagreement into personal animosity, with Huxley once describing Owen as having “a mendacity that is incomprehensible except on the assumption of a certain amount of moral obliquity.” The rivalry reached its climax in the debates following Darwin’s publication of “On the Origin of Species,” with Owen opposing evolutionary theory while Huxley became its most vigorous defender. Their public confrontations in scientific journals, at meetings of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, and through proxies in the popular press brought paleontological disputes to public attention and helped shape Victorian society’s understanding of evolution, human origins, and the relationship between science and religion.

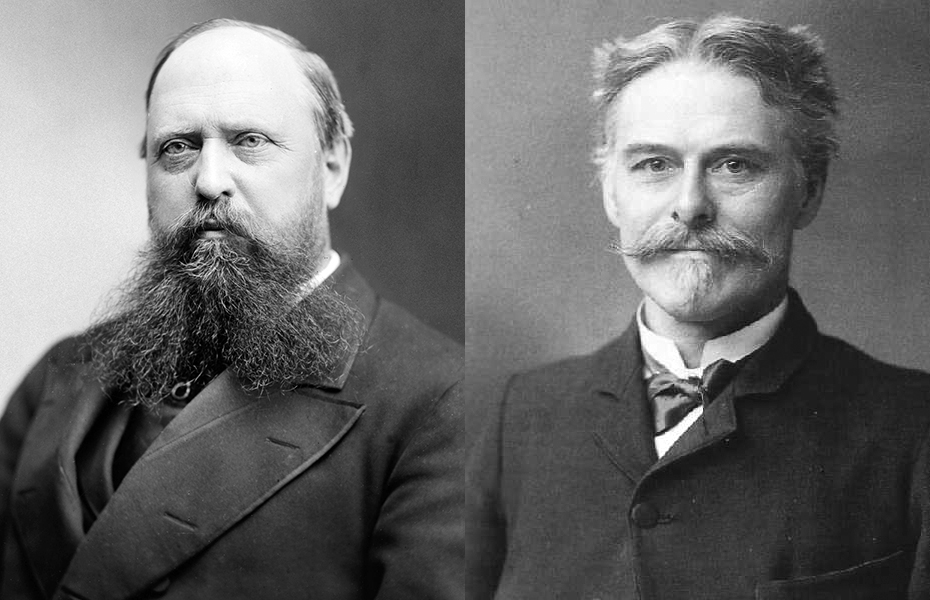

The Bone Wars: Competition Across the Atlantic

While British fossil hunters were engaged in their own rivalries, an even more dramatic and destructive competition unfolded in America between paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh. Beginning as colleagues and ending as bitter enemies, these scientists engaged in what became known as the “Bone Wars” – a frantic race to discover, name, and publish new dinosaur species from the American West. Their competitive zeal led them to employ unethical tactics including bribery, theft, sabotage of each other’s dig sites, and the deliberate destruction of fossils to prevent rivals from obtaining them. The financial and personal costs were enormous – Cope died nearly bankrupt after spending his fortune on expeditions, while Marsh’s reputation suffered from allegations of scientific dishonesty. Despite these shortcomings, their combined efforts resulted in the discovery of over 130 new dinosaur species including iconic specimens like Triceratops, Stegosaurus, and Allosaurus. The scientific competition that began in Victorian Britain thus found its most extreme expression in the American frontier, demonstrating how the prestige associated with paleontological discovery had become international in scope by the late nineteenth century.

Fossils and Faith: Religious Controversies

The proliferation of fossil discoveries in the Victorian era created profound theological challenges for a society steeped in traditional Christian beliefs about creation. Mounting evidence of extinct species, geological strata suggesting immense time periods, and anatomical similarities between fossil creatures and living animals all contributed to a growing crisis of faith for many Victorians. Clergymen-scientists attempted various reconciliations between scripture and the fossil record, with theories like Philip Henry Gosse’s “Omphalos” hypothesis suggesting God had created the world with fossils already embedded in rocks to test human faith. Others, like the Reverend William Buckland, incorporated fossils into religious narratives by interpreting geological layers as evidence of Noah’s flood or multiple divine creation events. The publication of Charles Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species” in 1859 intensified these debates, with fossils serving as key evidence for his evolutionary theory. The famous Oxford debate of 1860 between Thomas Henry Huxley and Bishop Samuel Wilberforce represented the public culmination of this tension between paleontology and traditional faith. For many Victorian fossil hunters, their scientific pursuits required complicated negotiations between religious upbringing and mounting evidence that contradicted literal biblical interpretation, leading some to abandon faith entirely while others developed more nuanced theological positions that accommodated both science and spirituality.

Women Breaking Boundaries in Paleontology

Despite formidable social barriers, numerous women beyond Mary Anning made significant contributions to Victorian paleontology, often finding creative ways to circumvent gender restrictions. Elizabeth Philpot, who collaborated with Anning, assembled an important collection of fossil fish and developed techniques for preserving fossil ink sacs. The wealthy aristocrat Barbara Hastings, Marchioness of Hastings, built one of the era’s finest private fossil collections and conducted field research personally despite societal disapproval of women engaging in such physical pursuits. Across the Atlantic, Annie Alexander founded and funded the University of California’s Museum of Paleontology, personally leading fossil-hunting expeditions into remote terrain. Many women participated as “invisible assistants” – wives, sisters, and daughters who prepared specimens, illustrated findings, organized collections, and sometimes wrote portions of scientific papers that were published under male relatives’ names. Educational opportunities gradually expanded, with universities slowly beginning to admit female students in the late Victorian period, though full participation in scientific societies remained largely closed to women until well into the 20th century. These pioneering women paleontologists demonstrated remarkable determination, often sacrificing social approval and marriage prospects to pursue their scientific passions in a society that viewed such intellectual ambitions as unfeminine and potentially harmful to women’s health.

The Museum Revolution and Public Engagement

The Victorian era witnessed a transformation in natural history museums from private curiosity cabinets to grand public institutions, with fossil displays at their center. The founding of the Natural History Museum in London in 1881, separate from the British Museum, represented the culmination of this movement, creating dedicated spaces where the public could encounter evidence of prehistoric life. Museum architecture itself reflected the new scientific understanding, with many institutions adopting evolutionary sequences in their displays to show the progression of life forms through geological time. Fossil specimens became centerpieces of these public collections, with complete dinosaur skeletons in particular drawing unprecedented crowds of visitors from all social classes. Public lectures on paleontology attracted large audiences, while affordable illustrated publications brought fossil discoveries to wider readerships. The Crystal Palace dinosaur models in London, though scientifically inaccurate by modern standards, represented the first attempt to create life-sized reconstructions of extinct animals for public education and entertainment. This democratization of paleontological knowledge contributed to broader social changes, as working-class people gained access to scientific ideas that had previously been the domain of educated elites, undermining traditional authority structures and contributing to the secularization of Victorian society.

Fossil Collecting as a Victorian Pastime

Beyond the professional realm, fossil hunting became a popular recreational activity across Victorian society, practiced by people of various social backgrounds. The growing railway network made previously inaccessible geological sites reachable for day trips, while inexpensive popular guides like “Fossil Hunting for Amateurs” provided practical instruction to novices. Middle-class families often spent seaside holidays searching for fossils along coastal exposures, combining healthy outdoor exercise with educational enrichment in a manner that perfectly aligned with Victorian values. Children’s collections were encouraged as morally uplifting pursuits that developed patience, observational skills, and appreciation for natural order. Women, restricted from many public activities, found fossil collecting an acceptable outdoor pursuit that allowed for scientific engagement within the bounds of propriety, particularly when conducted as family groups. Local fossil clubs and natural history societies flourished in industrial towns and rural parishes alike, holding regular meetings where members could display finds and hear lectures on geological topics. This widespread amateur engagement with fossils helped normalize evolutionary concepts in Victorian society, as ordinary citizens could see for themselves the evidence of extinct creatures and changing life forms over time, gradually shifting public opinion on controversial scientific theories through direct personal experience with the fossil record.

Colonial Fossil Hunting and Imperial Science

The Victorian era coincided with the expansion of the British Empire, creating new opportunities for fossil hunters to explore previously unstudied geological formations across the globe. British colonial administrators, military officers, and missionaries frequently collected fossils as a sideline to their official duties, sending specimens back to institutions in London, Edinburgh, and Oxford. These colonial fossil networks extended British scientific influence while expanding paleontological knowledge, uncovering extinct fauna from the Himalayas to Australia and South Africa. The 1862 discovery of Archaeopteryx in Germany became an international scientific sensation and bidding war, with the British Museum ultimately securing this crucial evolutionary missing link between reptiles and birds for the national collection, demonstrating how fossil acquisition became entangled with national prestige. Colonial fossil hunting also reflected Victorian racial attitudes, with indigenous knowledge of fossil locations often appropriated without credit, and local interpretations of fossils dismissed as superstition rather than recognized as valid traditional knowledge. By the late Victorian period, American and German institutions began mounting their own colonial expeditions, creating international competition for the most significant specimens that mirrored broader imperial rivalries. This global expansion of paleontology created the foundation for our modern understanding of prehistoric biogeography and evolutionary patterns across continents, though it occurred within problematic colonial power structures that privileged European interpretations over indigenous perspectives.

Technological Innovations in Victorian Fossil Hunting

Victorian fossil hunters developed numerous scientific and technical innovations that transformed paleontology from casual collecting into rigorous science. Field techniques evolved substantially, with pioneers like William Buckland developing systematic approaches to excavation that preserved crucial contextual information about fossil discoveries rather than merely extracting appealing specimens. Laboratory methods advanced similarly, including Anning’s techniques for exposing delicate specimens using specially adapted tools and Huxley’s improved microscopy methods for examining fossil microstructures. The challenge of transporting fragile fossils from remote locations led to the development of plaster jacketing—a technique still used today—where specimens are wrapped in bandages soaked in plaster of Paris to create protective casings. Documentation standards improved dramatically, with detailed field notes, precise geological maps, and professional scientific illustrations becoming standard practice by mid-century. Photography, emerging during this period, was quickly adopted for fossil documentation, allowing more accurate recording of specimens than hand drawings alone could provide. By the late Victorian era, paleontologists had established standardized nomenclature systems, publication protocols, and specimen preparation techniques that created a foundation for the modern discipline, transforming what had begun as gentleman’s hobby into a sophisticated scientific field with consistent methodological standards.

The Legacy of Victorian Fossil Hunters

The contributions of Victorian fossil hunters extend far beyond their immediate discoveries, shaping science and culture in ways that continue to resonate today. The specimens they collected form the core of major museum collections worldwide, providing an irreplaceable scientific resource for modern researchers studying evolution, extinction, and climate change. The theoretical frameworks they developed—particularly regarding geological time, extinction as a natural process, and anatomical connections between fossil and living species—laid essential groundwork for Darwin’s theory of evolution and subsequent biological understanding. Their public engagement efforts created enduring institutional structures for science communication, establishing museums, popular publications, and lecture traditions that continue to make paleontology one of the most accessible sciences to the general public. The social dynamics of Victorian fossil hunting have also provided important case studies for historians of science examining how gender, class, and colonial power structures influence scientific knowledge production, leading to reassessments of previously marginalized contributors like Mary Anning. Perhaps most significantly, the Victorian fossil hunters helped transform Western cultural understanding of time itself, expanding humanity’s conceptual horizon from biblical chronologies measured in thousands of years to the vast geological timescales in which we now locate ourselves—a profound shift in perspective that fundamentally altered how humans understand their place in natural history.

The Victorian fossil hunters embodied the contradictions of their age—simultaneously progressive in their scientific thinking yet often constrained by social conventions; driven by genuine curiosity yet engaged in bitter personal rivalries; expanding human knowledge while sometimes reinforcing existing power structures. Their efforts transformed paleontology from scattered observations into a cohesive scientific discipline with standardized methods, established institutions, and theoretical frameworks that continue to guide research today. The fossils they unearthed didn’t merely fill museum cases; they fundamentally altered humanity’s understanding of life’s history, Earth’s age, and our own place in the natural world. As we continue to build on their discoveries and correct their misconceptions, we remain indebted to these hammer-wielding pioneers who quite literally