In the popular imagination, dinosaurs often roam through lush tropical landscapes or arid deserts. However, paleontological evidence increasingly suggests a more complex picture of these ancient creatures and their environmental adaptations. While we commonly associate dinosaurs with warm climates, fossil discoveries and anatomical studies indicate that some dinosaur species may have been well-equipped to handle cold temperatures and even snowy conditions. This article explores the fascinating evidence for cold-tolerant dinosaurs and the various adaptations that might have helped them survive in chilly environments, challenging our traditional view of these magnificent prehistoric animals.

The Misconception of Dinosaurs as Purely Tropical Creatures

For decades, scientists and the public alike envisioned dinosaurs as inhabitants of exclusively warm, tropical environments. This misconception stemmed partly from early fossil discoveries concentrated in warmer regions and the initial classification of dinosaurs as reptiles, which are typically cold-blooded animals that thrive in heat. The early paleontological narrative failed to account for the Earth’s changing climate over the Mesozoic Era, which spanned approximately 180 million years. During this vast timeframe, the planet experienced various climate shifts, including periods of global cooling. Additionally, even during warmer global periods, polar regions and high elevations would have experienced seasonal cold and potential snowfall, creating environments where cold-adapted dinosaurs could have evolved and thrived. This broader understanding of prehistoric climate variability has forced scientists to reconsider dinosaurs’ temperature tolerances and adaptations.

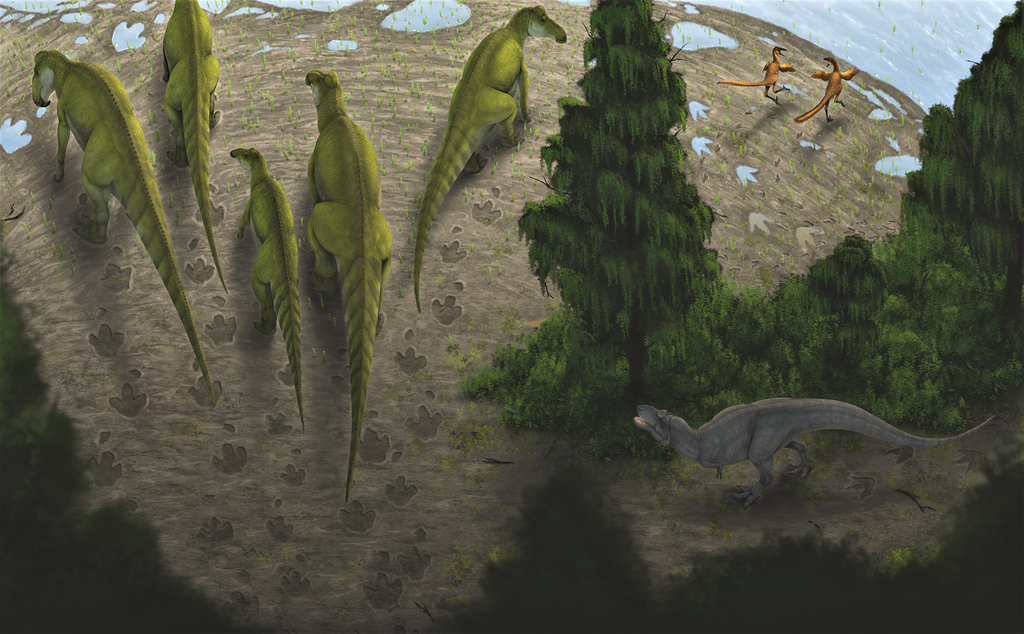

Polar Dinosaurs: Evidence from High Latitudes

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for cold-tolerant dinosaurs comes from fossil discoveries in ancient polar regions. Remarkable finds in places like Alaska, northern Canada, Australia (which was closer to the South Pole during the Mesozoic), and Antarctica have revealed diverse dinosaur communities that lived at high latitudes. These polar dinosaurs endured conditions dramatically different from their tropical counterparts, including months of darkness during winter and significantly colder temperatures. The Alaskan North Slope, for example, has yielded fossils of hadrosaurs, ceratopsians, and small theropods that lived approximately 70 million years ago when the region experienced temperatures that likely dropped below freezing during winter months. Similarly, discoveries in southeastern Australia have uncovered evidence of small ornithopods and theropods that survived in a cold, dark environment close to the ancient South Pole. These findings strongly suggest that at least some dinosaur lineages possessed adaptations allowing them to thrive in seasonally cold environments rather than migrating to warmer regions.

Cretaceous Climate and Seasonal Challenges

While the Mesozoic Era is often characterized as a greenhouse period with generally warmer global temperatures than today, significant temperature variations existed both geographically and seasonally. During the Late Cretaceous period (100-66 million years ago), polar regions experienced mean annual temperatures estimated between 0-10°C (32-50°F), with winter temperatures dropping below freezing. Paleoclimate data from fossil plants, sediments, and oxygen isotope analyses confirm that these polar regions experienced freezing conditions and likely snowfall during winter months. The seasonal challenges faced by polar dinosaurs included not just cold temperatures but also reduced food availability during winter and the psychological stress of prolonged darkness. Despite these challenging conditions, fossil evidence shows diverse dinosaur communities persisted in these environments, suggesting they possessed physiological or behavioral adaptations to cope with seasonal extremes. This climatological context provides crucial evidence that at least some dinosaur species must have developed cold-tolerance mechanisms to survive in these demanding environments.

Warm-Bloodedness and Dinosaur Thermoregulation

The question of dinosaur thermoregulation lies at the heart of their potential cold tolerance. Traditional views classified dinosaurs as ectothermic (cold-blooded) like modern reptiles, which would have made survival in cold environments nearly impossible. However, modern paleontological consensus has shifted dramatically toward viewing many dinosaur groups as endothermic (warm-blooded) or having unique intermediate metabolic strategies. Evidence for warm-bloodedness comes from multiple sources, including bone microstructure showing rapid growth rates typical of endothermic animals, the presence of respiratory turbinates that help conserve water and heat in fast-breathing animals, and the discovery of dinosaurs in polar environments where ectotherms could not maintain adequate body temperatures. Endothermy would have allowed dinosaurs to generate internal heat regardless of external temperatures, making survival in cold conditions physiologically possible. Some researchers propose that different dinosaur groups had varying metabolic rates, with small theropods (including the ancestors of birds) being fully endothermic, while larger sauropods might have used gigantothermy—maintaining stable body temperatures through sheer body mass—combined with elevated metabolic rates.

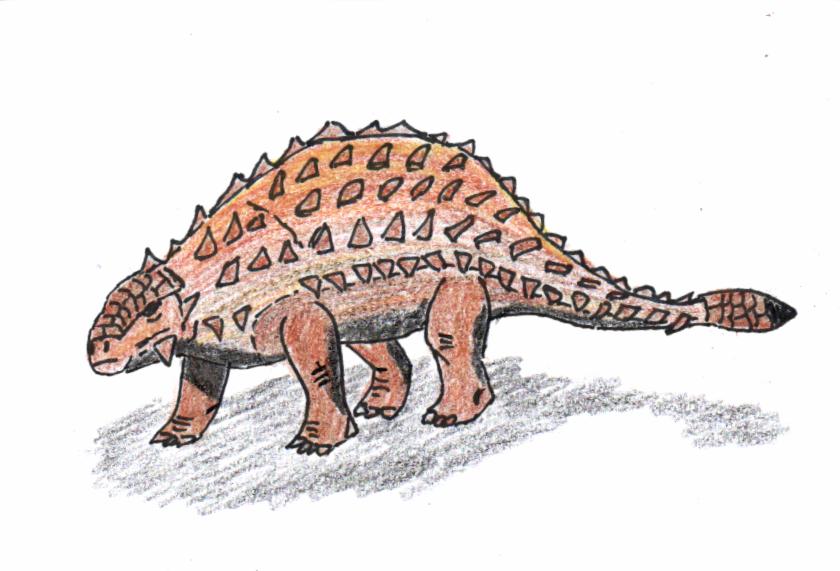

Insulation: Feathers, Proto-Feathers, and Fur-Like Coverings

One of the most revolutionary discoveries in paleontology over the past few decades has been the widespread presence of feathers and feather-like structures among dinosaurs. Particularly among theropods (the group that includes Tyrannosaurus rex and the ancestors of modern birds), evidence of feathery coverings has transformed our understanding of dinosaur appearance and physiology. These integumentary structures would have provided crucial insulation in cold environments, trapping a layer of warm air against the body. Remarkably, some of the best-preserved feathered dinosaur fossils come from regions that experienced cool temperatures, such as Yutyrannus huali, a 9-meter long tyrannosaur relative from Early Cretaceous China that possessed primitive feathers. Other dinosaur groups, including certain ornithischians like Kulindadromeus from Siberia, show evidence of different types of filamentous coverings that may have served insulating functions. The presence of these insulating structures strongly suggests that many dinosaur species were pre-adapted for cold tolerance, with their “fuzzy” coverings serving the same function that fur provides for mammals in cold environments.

Size Adaptations and Bergmann’s Rule

Body size plays a critical role in how animals adapt to cold environments, often following Bergmann’s rule—the principle that populations and species of larger size are found in colder environments, while smaller sizes dominate in warmer regions. This pattern emerges because larger bodies have a lower surface-area-to-volume ratio, allowing them to retain heat more efficiently. Interestingly, some polar dinosaur discoveries appear to support this pattern. For example, certain Arctic hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) were notably larger than their lower-latitude relatives, potentially representing an adaptation to colder climates. However, the fossil record also shows examples that contradict this pattern, with some small-bodied dinosaurs thriving in polar regions. These smaller species likely relied more heavily on insulation from feathers or other coverings rather than body size alone. The complex relationship between dinosaur body size and latitude suggests that different dinosaur lineages employed varied strategies for thermal regulation, combining metabolic adaptations, insulation, and body size to meet the challenges of their specific environments.

Behavioral Adaptations for Cold Survival

Beyond physiological adaptations, dinosaurs likely employed various behavioral strategies to cope with cold conditions, similar to modern animals. Seasonal migration represents one possibility, with some dinosaur species potentially traveling hundreds of kilometers to escape the harshest winter conditions. However, for many species, especially smaller ones, such long-distance travel would have been impractical or impossible. Hibernation or a state of torpor during the coldest months might have been another strategy, allowing dinosaurs to lower their metabolic requirements when food was scarce. Communal behavior offers another potential adaptation, with evidence of dinosaurs living in herds or groups that could huddle together for warmth during cold periods. Some fossil sites show evidence of multiple individuals preserved together, potentially indicating such social behaviors. Additionally, dinosaurs might have engaged in behavioral thermoregulation by seeking microhabitats that provided shelter from extreme cold, such as forests that moderated temperature fluctuations or geothermally warmed areas. While direct evidence for these behaviors is limited in the fossil record, they represent plausible strategies based on the behaviors observed in modern animals facing similar environmental challenges.

Dinosaur Nesting in Cold Environments

The discovery of dinosaur nesting sites in ancient polar regions provides fascinating insights into how these animals reproduced in cold environments. Remarkably, fossil evidence from Alaska and other high-latitude locations shows that some dinosaur species nested permanently in these regions rather than migrating to lay eggs. This behavior suggests they possessed adaptations for successful reproduction despite challenging conditions. Some nesting strategies might have included building vegetation-filled nests that generated heat through decomposition, similar to modern megapode birds. Others may have directly incubated their eggs, with the adults using body heat to maintain appropriate egg temperatures. The timing of reproduction would have been crucial, with egg-laying likely synchronized with the brief polar summer when temperatures were warmer and food more abundant. The successful reproduction of dinosaurs in these environments reinforces the view that they were not simply visitors to cold regions but permanent residents with sophisticated adaptations for the full lifecycle in challenging climates.

Evidence from Bone Histology and Growth Patterns

The microscopic structure of dinosaur bones provides valuable clues about their growth patterns and potential cold adaptations. Studies of bone histology from polar dinosaurs show interesting features that may represent adaptations to seasonal environments. Some specimens display distinct growth rings (similar to tree rings) that indicate periodic slowing or cessation of growth, likely corresponding to the resource-limited winter months. This pattern differs from many low-latitude dinosaur species that show more continuous growth, suggesting polar dinosaurs had physiological mechanisms to cope with seasonal resource scarcity. Additionally, some polar dinosaur species show evidence of sustained growth during colder periods, indicating they remained active rather than entering full hibernation. The density and vascularization patterns in dinosaur bones also provide clues about their metabolism, with highly vascularized bones suggesting elevated metabolic rates capable of generating internal heat. Together, these histological features paint a picture of dinosaurs physiologically equipped to handle seasonal temperature variations and food scarcity in cold environments.

The Role of Dinosaur Respiratory Systems

Dinosaurs possessed a respiratory system remarkably different from most modern reptiles, featuring air sacs extending from the lungs into various parts of the skeleton. This avian-style respiratory system, most advanced in theropod dinosaurs but present to varying degrees across dinosaur groups, would have provided significant advantages in cold environments. The unidirectional airflow through this system is more efficient at extracting oxygen than the bidirectional breathing of mammals, allowing for higher metabolic rates necessary to generate internal heat. Additionally, the extensive air sac network throughout the body could have helped regulate temperature by controlling the distribution of warm air. The respiratory turbinates (thin, scroll-like bones) found in some dinosaur nasal passages would have helped conserve heat and moisture during respiration in cold, dry conditions. This sophisticated respiratory apparatus represents another piece of evidence suggesting many dinosaurs possessed the physiological infrastructure necessary for enduring cold temperatures, enabling them to maintain active lifestyles even during chilly conditions.

Cold-Adapted Dinosaur Species Examples

Several dinosaur species stand out as particularly compelling examples of cold adaptation. Edmontosaurus, a large hadrosaur found in Alaska, appears to have been a year-round resident of the Arctic region during the Late Cretaceous. Its robust build and evidence of specialized dentition for processing tough vegetation suggest adaptation to the seasonal plants available in polar forests. Troodon formosus, a small theropod found in Alaska and other northern regions, possessed one of the largest brain-to-body ratios among dinosaurs, suggesting advanced behavioral adaptations possibly related to surviving in challenging environments. Its large eyes would have been advantageous during the dim polar winters. Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum, an Arctic ceratopsian, shows unique cranial features that differ from its southern relatives, potentially representing adaptations to polar conditions. Among more basal dinosaurs, Cryolophosaurus from Antarctica represents one of the earliest large carnivorous dinosaurs and demonstrates that even Early Jurassic dinosaurs could thrive in polar environments. These examples span different dinosaur lineages and time periods, suggesting cold tolerance evolved multiple times throughout dinosaur evolution.

Comparing Dinosaur Cold Adaptations to Modern Animals

Examining how modern animals survive in cold environments provides valuable analogies for understanding dinosaur adaptations. Today’s cold-adapted birds, the living descendants of theropod dinosaurs, offer particularly relevant comparisons. Emperor penguins endure the Antarctic winter through a combination of dense feather insulation, social huddling, and specialized circulation that minimizes heat loss—strategies potentially employed by their dinosaur ancestors. Similarly, Arctic mammals like muskoxen demonstrate how large body size, insulation, and social behavior create effective cold-survival strategies. Modern reptiles generally avoid truly cold environments, but exceptions exist—the painted turtle can survive being frozen solid through specialized blood chemistry, suggesting the possibility of similar biochemical adaptations in some dinosaur species. The leatherback sea turtle maintains elevated body temperatures in cold water through a combination of large size, specialized circulation, and high metabolism, representing a modern parallel to how large dinosaurs might have maintained thermal homeostasis. These comparative examples help scientists reconstruct plausible mechanisms through which dinosaurs navigated cold environments, even when direct evidence from fossils is limited.

The Evolutionary Advantages of Cold Tolerance

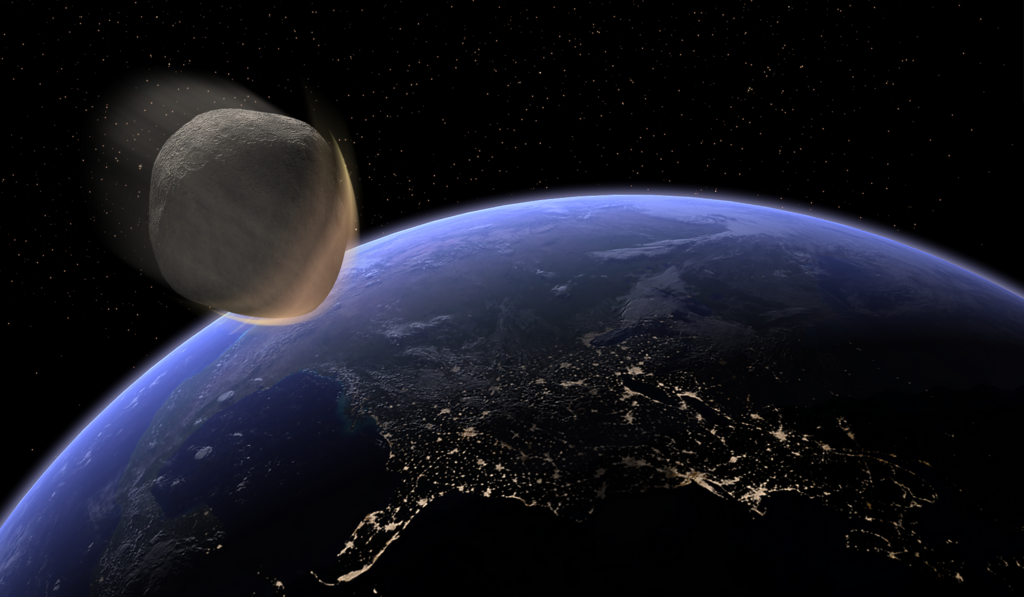

Developing cold tolerance offered significant evolutionary advantages for dinosaurs, extending far beyond simple survival. By adapting to cooler environments, dinosaurs could exploit ecological niches unavailable to strictly warm-adapted species, reducing competition for resources. Cold-tolerant species could expand their geographic ranges into higher latitudes and elevations, increasing their resilience against localized environmental disturbances and potentially explaining the remarkable global distribution of many dinosaur groups. During periods of global cooling, cold-adapted dinosaur lineages would have experienced selection advantages, potentially explaining why certain groups flourished while others declined during climate transitions. Additionally, the physiological adaptations for cold tolerance—including enhanced metabolism, improved insulation, and advanced respiratory systems—provided collateral benefits like increased stamina, improved thermoregulation in all environments, and enhanced growth rates. These advantages helped dinosaurs dominate terrestrial ecosystems for over 160 million years across varying climatic conditions. Ironically, the ultimate global cooling following the Chicxulub asteroid impact created conditions too extreme even for cold-adapted dinosaurs, with only the most specialized members—the ancestors of modern birds—surviving the ensuing nuclear winter.

Implications for Understanding Dinosaur Extinction

The evidence for cold-tolerant dinosaurs significantly impacts our understanding of their eventual extinction. The traditional narrative suggests that dinosaurs were ill-equipped for the rapid cooling following the Chicxulub asteroid impact 66 million years ago, giving mammals an advantage during this crisis. However, the existence of cold-adapted dinosaurs complicates this story, suggesting that temperature drop alone cannot explain the extinction pattern. Instead, it appears that the combination of multiple stressors—including darkness limiting plant growth, acid rain, wildfires, and subsequent food chain collapse—overwhelmed even cold-adapted dinosaurs. Interestingly, the only dinosaur lineage to survive—the ancestors of modern birds—possessed some of the most advanced cold-adaptations, including full feathering, high metabolic rates, and small body sizes that required less food during the crisis. This suggests that while cold tolerance was necessary for survival, it needed to be combined with other adaptations like dietary flexibility and reduced resource requirements. The extinction event thus represents not a simple case of cold-intolerance but a complex ecological catastrophe that exceeded the adaptive capacity of most dinosaur lineages, regardless of their impressive cold-weather adaptations.

Conclusion

The evidence for cold-tolerant dinosaurs fundamentally transforms our understanding of these remarkable animals. Far from being restricted to tropical paradises, dinosaurs conquered a wide range of environments through sophisticated adaptations including potential warm-bloodedness, insulating feathers, and behavioral strategies. The discovery of thriving dinosaur communities in ancient polar regions confirms that at least some species could handle freezing temperatures and seasonal snow. This cold-tolerance challenges simplistic explanations for dinosaur extinction and reveals these animals to be even more adaptable and resilient than previously thought. As paleontologists continue to uncover new evidence, our picture of dinosaurs evolves—not as climate-limited reptiles, but as diverse creatures whose adaptability allowed them to become one of Earth’s most successful groups of animals across a spectrum of environments, including those with long, snowy winters.