The popular image of dinosaurs often portrays them as voracious, indiscriminate eaters – tyrannosaurs tearing into any prey they could catch or long-necked sauropods stripping entire forests bare. However, recent paleontological discoveries have painted a much more nuanced picture of dinosaur dietary habits. Far from being opportunistic consumers of whatever organic matter was available, many dinosaur species appear to have been remarkably selective in their food choices. Through advanced research techniques including tooth wear pattern analysis, fossilized stomach contents, and comparative anatomy studies, scientists have uncovered evidence suggesting that dinosaurs exhibited specialized feeding behaviors and preferences that would qualify many as genuinely “picky eaters” by any reasonable definition. This selective eating likely played a crucial role in allowing different dinosaur species to coexist in the same ecosystems without directly competing for the same food resources.

The Evolution of Dinosaur Diet Studies

Understanding what dinosaurs ate has undergone a remarkable transformation over the past century. Early paleontologists made educated guesses about dinosaur diets based primarily on tooth morphology – sharp teeth for meat-eaters, flat teeth for plant-eaters. Today, researchers employ a sophisticated arsenal of analytical techniques, including stable isotope analysis of fossilized bones and teeth, microscopic examination of tooth wear patterns, and biomechanical modeling of jaw mechanics. These advanced approaches have revealed that dinosaur feeding strategies were far more complex than previously imagined. For instance, CT scanning technology now allows scientists to examine the internal structures of dinosaur skulls, revealing specialized sensory adaptations that would have helped certain species locate specific food items. This methodological revolution has transformed our understanding of prehistoric food webs and ecological relationships, showing that dinosaurs weren’t simply generalized feeders but often had remarkably specific dietary preferences.

Specialized Dental Equipment: Nature’s Custom Utensils

Dinosaur teeth were remarkably adapted to specific diets, functioning essentially as specialized tools for processing particular foods. The therizinosaurs, for example, possessed unusual leaf-shaped teeth perfectly suited for stripping specific types of vegetation, while avoiding others that might have been toxic or difficult to digest. Troodontids, small carnivorous dinosaurs, had serrated teeth with remarkably precise configurations that suggest they may have specialized in hunting particular prey items. Even among the famous Tyrannosaurus rex, tooth structure analysis suggests these apex predators may have preferred certain parts of carcasses, using their massive bone-crushing teeth to access nutritious marrow unavailable to other predators. Among hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs), the elaborate dental batteries consisting of hundreds of teeth allowed them to selectively process specific plant materials while rejecting others. These specialized dental adaptations strongly suggest that many dinosaurs weren’t opportunistic feeders but had evolved to exploit specific dietary niches.

Herbivorous Hauteur: Plant-Eating Specialists

The plant-eating dinosaurs display perhaps the clearest evidence of dietary specialization and selectivity. Rather than consuming all available vegetation, many herbivorous dinosaurs appear to have targeted specific plant types. The long-necked diplodocid sauropods, with their pencil-like teeth, appear to have selectively stripped soft leaves from conifers while avoiding tougher vegetation. In contrast, their relatives the titanosaurs had broader teeth that allowed them to consume different plant materials, creating a form of resource partitioning. Ankylosaurs, with their low-browsing habits and specialized jaws, likely focused on particular understory plants while ignoring others. Perhaps most strikingly, analysis of fossilized Edmontosaurus (a hadrosaur) stomach contents revealed a highly selective diet consisting primarily of specific conifer needles and twigs, suggesting these animals deliberately chose certain plant foods over others despite the abundance of other vegetation. This degree of selectivity challenges the notion that herbivorous dinosaurs simply consumed any plant material they encountered.

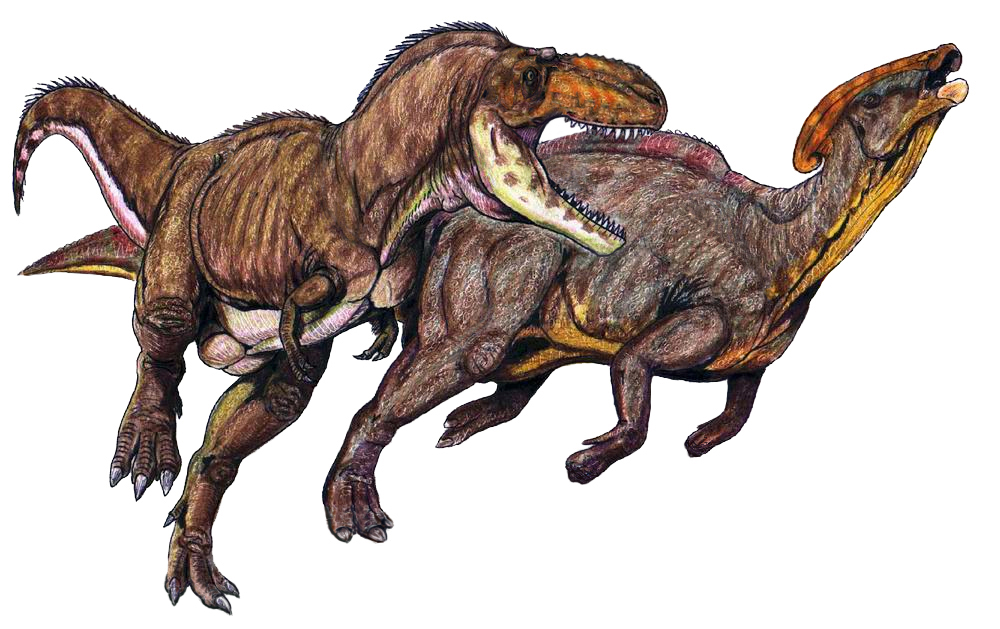

Carnivore Connoisseurs: Meat-Eating Preferences

Predatory dinosaurs also exhibited remarkable dietary specialization that goes far beyond simply hunting whatever prey was available. The small, bird-like compsognathids appear to have specialized in hunting lizards, with multiple fossil specimens preserved with lizard remains in their stomach cavities. Spinosaurids, with their crocodile-like snouts and specialized sensory organs, appear to have been selective fish hunters rather than generalized predators. Dromaeosaurids (the “raptors”) show adaptations suggesting they may have targeted specific prey types or even specific parts of carcasses. Microraptor, a small four-winged dinosaur, appears to have been specialized for hunting birds and tree-dwelling mammals in forest canopies. Even among the largest carnivores, evidence suggests possible specialization – Tyrannosaurus rex’s powerful jaws may have allowed it to target specific high-nutrient areas of prey like the nutrient-rich liver, leaving other less valuable parts for smaller scavengers. This evidence collectively suggests many carnivorous dinosaurs were selective predators with specific dietary preferences.

Evidence from Fossilized Stomach Contents

The ultimate smoking gun for dinosaur dietary preferences comes from the rare but invaluable discoveries of fossilized stomach contents, known as “bromalites.” These exceptional fossils provide direct evidence of an animal’s last meal, offering a window into specific food choices. The ornithomimid Sinornithomimus, often assumed to be an omnivore, was discovered with a stomach full of gastroliths (stomach stones) and specific seeds, suggesting a specialized plant diet rather than a generalized omnivorous one. A remarkable specimen of the small theropod Compsognathus was found with remains of a specific lizard species in its abdominal cavity, indicating targeted hunting of particular prey. The primitive ceratopsian Psittacosaurus has been found with selective collections of seeds and specific plant tissues in its digestive tract, indicating discriminating feeding habits. Perhaps most compelling is the “mummy” Edmontosaurus specimen that preserved actual stomach contents consisting primarily of specific conifer needles and particular fruits, demonstrating clear dietary selectivity despite the diversity of plants that would have been available. These direct lines of evidence conclusively demonstrate that many dinosaurs were indeed choosing specific foods rather than consuming whatever was available.

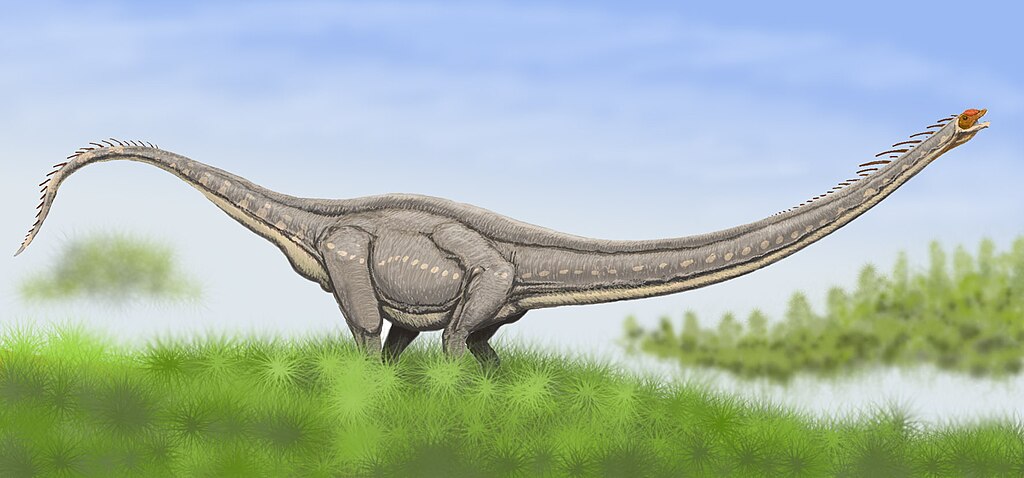

The Picky Sauropods: Not Just Indiscriminate Browsers

The enormous sauropods, despite their reputation as walking appetites that consumed vast quantities of vegetation, show surprising evidence of dietary selectivity. Different sauropod families had distinctly different tooth morphologies that appear adapted for specific types of vegetation. Diplodocids, with their pencil-like teeth arranged at the front of the mouth, appear to have selectively stripped soft foliage from branches while avoiding tougher vegetation. Camarasaurids, with their stronger, spoon-shaped teeth, specialized in different plant materials that required more crushing force. Isotope analysis of sauropod teeth has revealed different carbon signatures between co-existing species, indicating they were consuming different plant types rather than competing for the same resources. The remarkable vertical feeding range of these animals, with some species capable of reaching vegetation over 40 feet high while others browsed close to the ground, further suggests specialized feeding strategies rather than generalized consumption. This evidence dramatically revises our understanding of these giants, suggesting they were selective feeders despite their prodigious appetites.

Selective Feeding Based on Nutritional Needs

Growing evidence suggests dinosaurs may have selected specific foods to meet particular nutritional requirements, much like modern animals. Analysis of coprolites (fossilized feces) from herbivorous dinosaurs sometimes shows specific plant residues that would have provided particular nutrients, suggesting intentional selection. Some hadrosaur specimens show seasonal variation in tooth wear patterns, indicating they may have shifted food preferences throughout the year to meet changing nutritional needs. Certain dinosaurs appear to have consumed particular rocks as gastroliths, carefully selecting stones of specific sizes and compositions to aid in digestion of their preferred foods. Carnivorous dinosaurs may have targeted specific prey or prey body parts to obtain critical nutrients – a behavior observed in modern predators that selectively consume nutrient-rich organs. The massive Shantungosaurus, a hadrosaur the size of a full-grown elephant, appears to have selectively consumed certain conifers rich in specific compounds beneficial for their digestive processes. These behaviors suggest dinosaurs weren’t simply eating to satiate hunger but were making sophisticated food choices based on nutritional requirements.

Dinosaur Taste Buds: The Sensory Side of Selection

The question of whether dinosaurs could actually taste their food and make decisions based on flavor preferences has gained traction in recent paleontological discussions. Analysis of dinosaur brain cases, particularly in theropods closely related to birds, suggests many possessed the neurological structures necessary for taste perception. Studies of dinosaur tongues, based on hyoid bone structures (which support the tongue), indicate some species had muscular, dexterous tongues similar to modern birds and reptiles that use taste to evaluate food items. Genetic studies of living dinosaur descendants (birds) have identified taste receptor genes that likely existed in their dinosaur ancestors, suggesting they could perceive different flavors. Paleontologists have identified preserved oral tissues in some exceptionally preserved fossils that appear to show taste-related structures similar to those in modern animals. While we can’t know for certain if a Triceratops preferred the taste of certain cycads over others, the evidence suggests many dinosaurs possessed the sensory equipment to make such discriminations, potentially explaining some of their selective feeding behaviors.

Dietary Specialization in Ornithopods

The ornithopods, a diverse group including the famous duck-billed hadrosaurs, show some of the most compelling evidence for dietary selectivity among dinosaurs. These animals possessed the most sophisticated dental arrangements of any reptile, with complex dental batteries containing hundreds of teeth that were continuously replaced. Microscopic analysis of these teeth reveals distinctive wear patterns that differ between ornithopod species living in the same environments, indicating they were eating different plant materials. The elaborate cranial crests of some hadrosaurs, once thought to be purely for display, may have housed specialized sensory equipment that helped them locate or evaluate specific plant foods. Coprolites attributed to hadrosaurs sometimes contain concentrated remains of particular plant types rather than a diverse mixture, suggesting selective consumption. The varied beak shapes among different ornithopod species, from the broad bills of some hadrosaurs to the narrow beaks of hypsilophodonts, indicate specialization for harvesting particular plant parts. Together, this evidence paints a picture of ornithopods as highly discriminating plant-eaters with sophisticated feeding preferences.

Theropod Predators: Beyond Opportunistic Hunting

The carnivorous theropods, rather than being generalist predators taking any available prey, exhibit numerous adaptations suggesting specialized hunting and feeding preferences. The famous Velociraptor, with its sickle-shaped foot claw and relatively weak bite force, appears specialized for dispatching specific prey types rather than tackling any available animal. Spinosaurids evolved remarkably crocodile-like snouts with sensory pits and conical teeth perfectly adapted for catching slippery fish, suggesting a highly specialized piscivorous (fish-eating) diet rather than general carnivory. Tooth-marked bones indicate some theropods may have consistently targeted specific parts of carcasses, ignoring other available tissues. The diminutive Microraptor shows adaptations for pursuing specific prey in forest canopies, with four winged limbs that allowed it to chase particular arboreal prey species. Stable isotope analyses of theropod teeth sometimes show signatures consistent with specialized rather than generalized diets. These patterns suggest that theropods weren’t simply opportunistic killers but had evolved to exploit specific predatory niches, often avoiding direct competition with other carnivores by focusing on different prey types.

Coexisting Through Dietary Differentiation

One of the most compelling reasons to believe dinosaurs were selective eaters comes from examining diverse dinosaur communities where multiple species coexisted in the same habitats. The famous Late Cretaceous ecosystems of western North America supported numerous large herbivores including several hadrosaur species, multiple ceratopsians, ankylosaurs, and pachycephalosaurs simultaneously. This coexistence was possible largely because each group specialized in different food resources rather than competing directly. Similarly, predatory dinosaurs in the same environments, from massive tyrannosaurids to mid-sized dromaeosaurids to tiny troodontids, appear to have focused on different prey types or hunting strategies. The Morrison Formation of the Late Jurassic supported multiple sauropod species simultaneously, with diplodocids, camarasaurids, and brachiosaurids all coexisting through dietary niche partitioning. The principle of competitive exclusion in ecology suggests this level of coexistence would have been impossible without significant dietary specialization among these dinosaurs. Their success in developing complex, diverse ecosystems for over 150 million years suggests dinosaurs weren’t generalists but highly adapted specialists each filling specific ecological niches.

Modern Analogues: Lessons from Living Relatives

The living descendants of dinosaurs – birds – provide valuable insights into potential feeding behaviors of their extinct relatives. Modern birds display remarkably diverse and often highly specialized feeding strategies, from the specialized bill of flamingos for filter feeding to the hooked beaks of eagles for tearing specific prey tissues. This diversity suggests their dinosaur ancestors may have shown similar specialization. Many modern reptiles, including crocodilians (the closest living relatives to dinosaurs besides birds), exhibit surprisingly selective feeding behaviors despite their reputation as indiscriminate predators. Young crocodiles focus on insects and small fish, while adults target specific prey types based on size and habitat. Studies of bird digestive systems show many species have evolved specialized gut anatomy to process particular foods – a pattern likely present in their dinosaur ancestors. The dietary selectivity seen in modern herbivorous reptiles like iguanas, which can distinguish between toxic and non-toxic plants, suggests herbivorous dinosaurs likely possessed similar discriminatory abilities. These modern examples reinforce the likelihood that dinosaurs weren’t indiscriminate feeders but had evolved specific dietary preferences and specializations.

Implications for Understanding Dinosaur Ecology

Recognizing dinosaurs as selective eaters rather than generalist consumers fundamentally changes our understanding of prehistoric ecosystems and evolutionary dynamics. Dietary specialization helps explain how incredibly diverse dinosaur communities could coexist without excessive competition for resources, with different species focusing on different food sources within the same environment. The recognition of dinosaurs as selective feeders suggests they played more specific and varied ecological roles than previously thought, potentially functioning as keystone species that influenced the evolution of certain plant groups through selective consumption. Understanding dinosaur dietary preferences provides insights into extinction patterns, as highly specialized feeders would have been more vulnerable to environmental changes that affected their specific food sources. This perspective also illuminates dinosaur evolution, suggesting that many unusual anatomical features evolved not just for combat or display but as adaptations for accessing specific food resources unavailable to other species. By recognizing dinosaurs as discriminating diners rather than indiscriminate consumers, paleontologists gain a more nuanced understanding of the complex ecological relationships that shaped the Mesozoic world for over 150 million years.

Conclusion

Far from being opportunistic feeders consuming whatever crossed their paths, the evidence overwhelmingly suggests many dinosaurs were indeed selective eaters with specific dietary preferences. From the specialized teeth of hadrosaurs to the fish-hunting adaptations of spinosaurs, from the selective browsing of sauropods to the specialized predatory tactics of dromaeosaurids, dinosaurs evolved remarkable adaptations for targeting specific foods while avoiding others. This dietary specialization helps explain how such diverse dinosaur communities could coexist in shared environments and sheds new light on their ecological relationships. As paleontological techniques continue to advance, we’re likely to discover even more evidence of dinosaur dietary preferences, further refining our understanding of these remarkable animals not as indiscriminate eating machines but as sophisticated organisms with specific tastes and feeding strategies finely tuned to their particular ecological niches.