The image of dinosaurs in popular culture often depicts them as either solitary predators or vast herds of plant-eaters moving across prehistoric landscapes. This dichotomy raises intriguing questions about dinosaur behavior that paleontologists have been investigating for decades. Were some dinosaurs truly social creatures with complex group dynamics similar to modern elephants or primates? Or were they merely tolerant of one another’s presence, gathering together only for practical reasons like protection or feeding opportunities? The distinction between genuine sociality and simple tolerance is crucial for understanding these ancient creatures and their ecosystems. Recent fossil discoveries and innovative research methods have begun to shed new light on this fascinating aspect of dinosaur paleobiology, revealing a more nuanced picture than previously thought.

Defining Sociality in Extinct Animals

Studying social behavior in extinct animals presents unique challenges for paleontologists. Unlike with living species, scientists cannot directly observe interactions between dinosaurs, making it necessary to rely on indirect evidence. True sociality involves complex, cooperative behaviors, communication systems, and potentially social hierarchies—all difficult to determine from fossil evidence alone. Researchers must therefore establish clear criteria to distinguish between genuine social behavior and simple tolerance or coincidental grouping. These criteria often include evidence of coordinated activities, parental care, communication structures, and consistent group living across multiple sites and periods. The challenge is further complicated by taphonomic biases—how preservation processes can create misleading patterns in the fossil record that might be mistaken for behavioral signals.

The Evidence from Mass Death Assemblages

One of the most compelling lines of evidence for potential dinosaur sociality comes from mass death assemblages—sites where multiple individuals died and were fossilized together. Famous examples include the Centrosaurus bone beds in Alberta, Canada, which contain thousands of individuals that appear to have died together during flooding events. Similarly, sites containing multiple Allosaurus or Mapusaurus specimens suggest these predators may have been together at the time of death. However, mass death sites require careful interpretation, as animals might congregate for reasons other than social bonds, such as around water sources during droughts. Paleontologists analyze the age profiles, preservation conditions, and geological context of these assemblages to determine whether they represent genuinely social groups or coincidental gatherings. When mass death sites show consistent age distributions across multiple locations, the case for sociality becomes stronger.

Trackway Evidence and Group Movements

Fossil footprints provide another window into potential dinosaur social behavior, capturing moments of movement frozen in time. Multiple parallel trackways of the same species moving in the same direction suggest coordinated group movement rather than random encounters. Notable examples include sauropod trackways from the Middle Jurassic of Yorkshire, England, and hadrosaur tracks from western North America, which show evidence of multiple individuals traveling together while maintaining consistent spacing. The orientation, spacing, and size variation within these trackways can reveal information about group composition and organization. Some hadrosaur trackways, for instance, show a pattern of larger (presumably adult) tracks on the periphery with smaller (juvenile) tracks protected in the center—a pattern reminiscent of protective herding behaviors seen in modern elephants. Such preserved movement patterns provide some of the strongest evidence for coordinated group behavior in certain dinosaur species.

Nesting Sites and Colonial Breeding

The discovery of extensive dinosaur nesting grounds has revolutionized our understanding of potential social behavior in these ancient reptiles. Sites like “Egg Mountain” in Montana have revealed multiple Maiasaura nests nearby, suggesting colonial nesting similar to that seen in modern birds. The consistent spacing between nests at many sites indicates these weren’t random placements but coordinated breeding colonies. Evidence from some nesting sites also suggests parental care, with nests containing juvenile remains showing signs of extended nest occupation and potential feeding by parents. The oviraptorid dinosaur Citipati has been found fossilized in brooding positions atop nests, similar to modern birds, indicating parental investment. Colonial nesting doesn’t automatically prove complex sociality, as many modern reptiles nest communally without forming social bonds, but it does suggest at minimum a high degree of tolerance and potentially coordinated breeding behaviors.

Brain Structure and Social Capacity

Advances in paleoneurology—the study of ancient brain structures—have provided insights into dinosaurs’ potential capacity for social behavior. By examining endocasts (natural casts of brain cavities) or using CT scanning to visualize brain structure, researchers can estimate the relative size of brain regions associated with sensory processing, communication, and social cognition. Some dinosaurs, particularly certain theropods and ornithischians, show enlarged cerebral hemispheres and optic lobes that might have supported more complex behavioral repertoires. Troodontids and dromaeosaurids had relatively large brains for their body size, with proportions approaching those of primitive birds, suggesting potential for more sophisticated behaviors. However, brain structure alone cannot definitively prove sociality, as many solitary animals also have complex brains. The cerebral expansion in some dinosaur lineages does suggest these animals possessed the neural hardware that could support social interactions, even if it doesn’t confirm they engaged in them.

Case Study: Theropod Pack Hunting

The question of whether large predatory theropods engaged in cooperative hunting has fascinated both scientists and the public. Some fossil sites provide tantalizing hints of potential pack behavior in certain species. The Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry in Utah, with its unusual concentration of Allosaurus remains, has been interpreted by some researchers as evidence of pack hunting gone wrong, with multiple predators becoming trapped while pursuing prey. Similarly, sites in Argentina have revealed multiple specimens of the giant carcharodontosaurid Mapusaurus found together, suggesting possible group activity. Perhaps the strongest case comes from dromaeosaurids like Deinonychus, whose remains have been found associated with much larger prey animals that would have been difficult for a single individual to subdue. Critics note that modern predatory reptiles rarely hunt cooperatively, and these fossil associations could represent scavenging aggregations rather than coordinated hunting parties. The debate continues, highlighting the challenge of distinguishing genuine social hunting from opportunistic gathering at feeding sites.

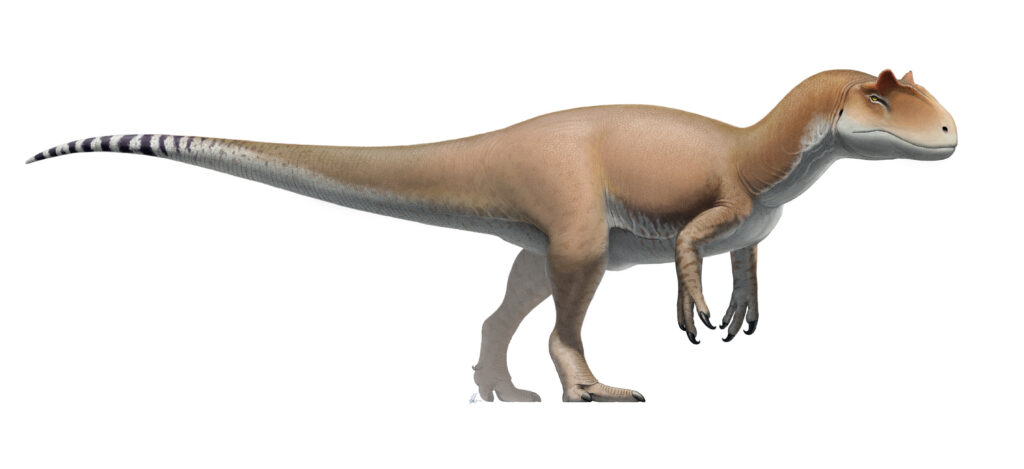

Ornithischian Social Structures

Ornithischian dinosaurs—including hadrosaurs, ceratopsians, and ankylosaurs—have provided some of the most compelling evidence for potential complex sociality. The extensive bone beds of ceratopsians like Centrosaurus and Pachyrhinosaurus suggest these horned dinosaurs may have lived in large aggregations. Age profiles from these sites often include individuals ranging from juveniles to adults, suggesting family groups rather than age-segregated herds. Some hadrosaur specimens show evidence of having recovered from serious injuries that would have required extended periods of reduced mobility, suggesting they may have received protection within a social group while healing. The discovery of the pachycephalosaur Pachycephalosaurus with healed cranial injuries has led some researchers to hypothesize that these dome-headed dinosaurs engaged in head-butting contests similar to modern rams, potentially as part of social dominance displays. These lines of evidence, while still circumstantial, build a case for more complex social structures in ornithischians than previously recognized.

Sauropod Aggregations: Social or Circumstantial?

The massive sauropod dinosaurs present an interesting case study in the sociality versus tolerance debate. Multiple sauropod track sites show evidence of groups moving in the same direction, and some fossil deposits contain multiple individuals of the same species. However, interpreting these patterns requires caution. Modern large herbivores often gather in groups for protection or to exploit patchy resources without necessarily forming complex social bonds. Some sauropod track sites show age segregation, with groups of similarly-sized individuals traveling together, which differs from the family group structure seen in truly social modern mammals like elephants. The sheer metabolic demands of these giant animals would have required constant movement to find sufficient food, potentially making prolonged social grouping impractical. Yet the consistent patterns of group movement seen at multiple track sites suggest at minimum a high degree of tolerance and possibly some level of coordinated movement. Whether this represents true sociality or simply pragmatic grouping remains debated.

Evolutionary Context: Reptile vs. Bird Sociality

Understanding dinosaur social behavior requires placing them in the proper evolutionary context between their reptilian ancestors and avian descendants. Modern reptiles generally show limited sociality, with few examples of complex social structures beyond basic parental care in some species. Birds, in contrast, display a wide range of social behaviors, from colonial nesting to cooperative breeding and complex flock dynamics. As dinosaurs—particularly theropods—are directly ancestral to birds, questions arise about when and in which lineages more complex social behaviors might have evolved. Some researchers propose that the evolution of feathers, which originally served functions other than flight, may have created new opportunities for visual display and communication that could support more complex social interactions. The discovery of elaborate display features like crests, frills, and feathers in many dinosaur species suggests they may have engaged in social signaling more complex than that seen in most modern reptiles. This evolutionary perspective suggests the possibility that some dinosaur groups were developing social behaviors that would later become more elaborate in their avian descendants.

Modern Analogues: Crocodilians and Birds

Examining the social behaviors of dinosaurs’ closest living relatives—birds and crocodilians—provides valuable context for interpreting fossil evidence. Modern crocodilians, while generally less social than many birds, do show some surprising social behaviors, including coordinated feeding strategies, communal nesting, and extended parental care. American alligators, for instance, create nursery pools where multiple females may guard young collectively. Birds display an even wider range of social behaviors, from simple flocking to the complex cooperative breeding systems seen in some species. These modern analogues demonstrate that complex sociality can evolve within archosaurs—the group containing crocodilians, dinosaurs, and birds. The presence of social behaviors in both major surviving archosaur lineages suggests their common ancestor may have possessed some baseline capacity for social interaction. This phylogenetic bracketing approach supports the hypothesis that at least some dinosaur groups likely exhibited social behaviors more complex than simple tolerance, particularly in lineages closely related to birds.

The Role of Environmental Factors

Environmental conditions likely played a crucial role in shaping dinosaur social behavior, just as they do for modern animals. Resource distribution, predation pressure, and climatic factors all influence whether sociality or solitary living provides greater survival advantages. In environments where resources were patchily distributed but locally abundant, such as seasonal wetlands favored by many hadrosaurs, group living might have been advantageous even without complex social bonds. Harsh seasonal conditions might have driven some species to migrate in groups, as suggested by some trackway evidence. Predation pressure could have selected for herding behaviors in vulnerable species while simultaneously favoring pack hunting in some predators. The Mesozoic world experienced several major environmental shifts, including changing continental configurations, sea level fluctuations, and climate changes. These changing conditions might have driven evolutionary shifts in social behavior over time, with different patterns emerging in different dinosaur lineages as they adapted to their specific ecological circumstances.

Technological Advances in Paleosociality Research

Recent technological innovations have revolutionized the study of potential dinosaur social behavior, allowing researchers to extract more information from fossil evidence than ever before. Advanced imaging techniques like computed tomography (CT) scanning can reveal internal bone structures that indicate growth patterns, potentially helping distinguish between individuals who grew up under different social conditions. Stable isotope analysis of fossil teeth and bones can provide insights into diet and migration patterns, potentially revealing whether individuals from the same site shared similar life histories consistent with group living. Sophisticated statistical methods for analyzing spatial patterns in bone beds and trackways can help distinguish between random aggregations and non-random groupings that might indicate social structure. Digital modeling of dinosaur sensory capabilities, based on detailed studies of skull anatomy, can suggest whether particular species had the sensory prerequisites for complex social communication. These technological approaches, combined with traditional paleontological methods, are creating a more nuanced understanding of dinosaur behavior that moves beyond simple dichotomies of “social” versus “non-social.”

Future Directions in Understanding Dinosaur Sociality

The study of dinosaur social behavior continues to evolve as new fossil discoveries and analytical methods emerge. Several promising research directions may yield further insights in the coming years. Expanded global sampling of dinosaur trace fossils—including tracks, nests, and feeding sites—across different environmental contexts could reveal whether social patterns varied by habitat or changed through time. More detailed studies of ontogenetic (developmental) changes in dinosaur bones might reveal whether individuals experienced different growth patterns depending on their social context, similar to how social versus solitary elephants show different growth trajectories. Advanced statistical methods comparing dinosaur social evidence to that of modern animals with known behavior patterns could help establish more objective criteria for identifying sociality in the fossil record. Integration of multiple lines of evidence—combining neuroanatomy, biomechanics, sensory biology, and traditional paleontological approaches—offers the most promising path forward for unraveling the complex question of dinosaur sociality. As these approaches develop, our understanding of dinosaur behavior will likely continue to shift away from simple categorizations toward recognition of a spectrum of social complexity across different dinosaur groups.

Conclusion

The question of whether dinosaurs were genuinely social creatures or merely tolerant of one another represents a fascinating frontier in paleontological research. The evidence suggests that dinosaur sociality likely existed along a spectrum, with different groups showing varying degrees of social complexity. Some lineages, particularly certain theropods closely related to birds and some ornithischians, show multiple lines of evidence consistent with complex social structures beyond mere tolerance. Others may have exhibited intermediate levels of sociality, gathering in groups for practical benefits without the elaborate social bonds seen in highly social modern animals. What seems increasingly clear is that the traditional view of dinosaurs as simply “reptilian” in their behavior underestimates their behavioral complexity. As with many aspects of dinosaur biology, their social lives were likely more diverse and sophisticated than previously recognized, reflecting the remarkable evolutionary success of these animals across 165 million years of Earth’s history. The ongoing research into dinosaur sociality not only enhances our understanding of these fascinating creatures but also provides insights into the evolution of social behavior across vertebrate evolution.