For centuries, paleontologists have been piecing together the puzzle of dinosaur diets through fossilized teeth, coprolites (fossilized feces), and skeletal adaptations. However, perhaps the most direct evidence comes from the rare and remarkable discovery of actual stomach contents preserved within dinosaur fossils. These extraordinary findings, known as gastric residues or gut contents, provide a literal snapshot of a dinosaur’s last meal, offering unprecedented insights into prehistoric food chains and feeding behaviors. By examining these fossilized meals, scientists can determine not just what dinosaurs ate but also how they processed food, their position in ancient ecosystems, and how their diets evolved over millions of years. This fascinating field of study continues to challenge and refine our understanding of these magnificent creatures that dominated Earth for over 165 million years.

The Rarity of Preserved Stomach Contents

Fossilized stomach contents are exceptionally rare treasures in the paleontological record. The conditions required for the preservation of soft tissues and partially digested food are remarkably specific, requiring rapid burial and unique chemical environments that prevent complete decomposition. For every thousand dinosaur skeletons discovered, perhaps only a handful contain identifiable stomach contents. This scarcity makes each discovery particularly valuable, with scientists meticulously analyzing every fragment and fiber. The preservation process typically involves mineralization, where the organic materials are replaced by minerals while maintaining their original structure. Some of the best-preserved examples come from fine-grained sedimentary deposits where dinosaurs were quickly entombed after death, such as ancient lake beds or areas of volcanic ash fall that rapidly buried the animals.

Techniques for Identifying Ancient Meals

Paleontologists employ an impressive array of techniques to identify fossilized stomach contents. Microscopic analysis allows scientists to examine cellular structures of plant materials or identify bone fragments from prey animals. Chemical analysis, including stable isotope studies, can reveal dietary preferences by examining the ratio of carbon and nitrogen isotopes preserved in tissues. Advanced imaging technologies such as CT scans permit non-destructive examination of fossils, revealing hidden stomach contents without damaging the specimen. Comparative anatomy plays a crucial role as researchers compare the discovered contents with known plants and animals from the same period and locality. Additionally, electron microscopy can reveal minute details, such as tooth marks on bones or the cellular structure of fossilized plant material, providing further clues about feeding mechanisms and digestion processes.

The Carnivorous Diet of Tyrannosaurus Rex

The eating habits of Tyrannosaurus rex have captivated scientists and the public alike, with fossilized evidence confirming its reputation as a fearsome predator. Stomach contents found in T. rex specimens include partially digested bones of other dinosaurs, particularly hadrosaurs and ceratopsians, supporting the view that these massive theropods hunted large prey. The bone fragments often show signs of powerful acid digestion, indicating the T. rex had a highly acidic stomach environment capable of breaking down bone. Interestingly, some specimens contain multiple prey species, suggesting opportunistic feeding behaviors rather than the specialized hunting of particular dinosaurs. The spacing and size of bone fragments in the stomach contents also provide clues about the T. rex’s feeding mechanics, supporting theories that these predators tore large chunks from carcasses and swallowed them with minimal chewing, relying on their powerful digestive system to process the food. This feeding strategy aligns with their massive skull design and serrated teeth, perfectly evolved for ripping flesh and crushing bone.

Herbivorous Dinosaurs and Their Plant-Based Diets

Fossilized stomach contents from herbivorous dinosaurs reveal sophisticated plant-processing capabilities that evolved over millions of years. Specimens of hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) have been found containing remains of conifer needles, twigs, seeds, and other plant materials, indicating they fed primarily on gymnosperms. Some sauropod discoveries show evidence of selective feeding on particular plant types, challenging the notion that these long-necked giants indiscriminately consumed vegetation. The preservation of gastroliths—stomach stones used to grind plant material—alongside plant remains offers insights into the mechanical digestion processes of these animals. Microscopic analysis of preserved plant cells shows evidence of the specific parts of plants consumed, from nutrient-rich shoots to fibrous stems. The diversity of plant material found in different herbivorous species demonstrates dietary specialization and niche partitioning among dinosaurs, allowing multiple species to coexist in the same ecosystems without direct competition for food resources.

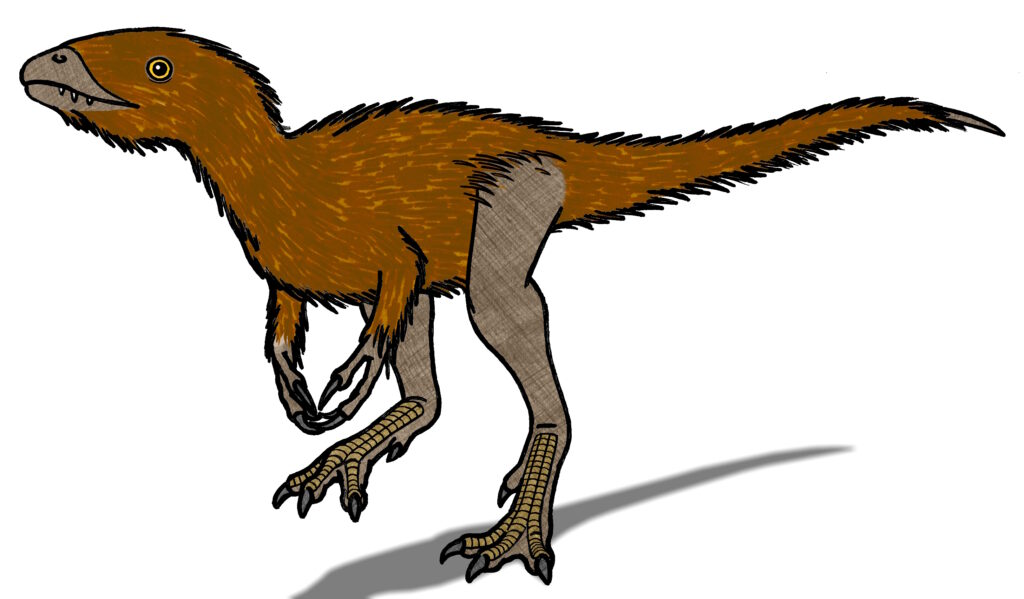

Omnivorous Dinosaurs: The Best of Both Worlds

Some dinosaur species exhibited omnivorous tendencies, consuming both plant matter and animal tissue, as evidenced by their fossilized stomach contents. Specimens of ornithomimids (ostrich-like dinosaurs) have revealed mixed content, including seeds, fruits, and small animal remains, suggesting a flexible diet that changed seasonally or opportunistically. The omnivorous Oviraptor, once thought to be an egg thief, has been found with stomach contents containing shellfish, seeds, and small vertebrates, indicating a varied diet that helped these dinosaurs adapt to changing environments. Gastric contents from juvenile dinosaurs sometimes differ from adults of the same species, suggesting dietary shifts throughout their life cycles. This dietary flexibility may have provided significant evolutionary advantages, allowing omnivorous dinosaurs to survive environmental changes and resource fluctuations that might have threatened more specialized feeders. The ability to process both plant and animal material also required specialized digestive adaptations, including dental structures that could both slice meat and crush plant material.

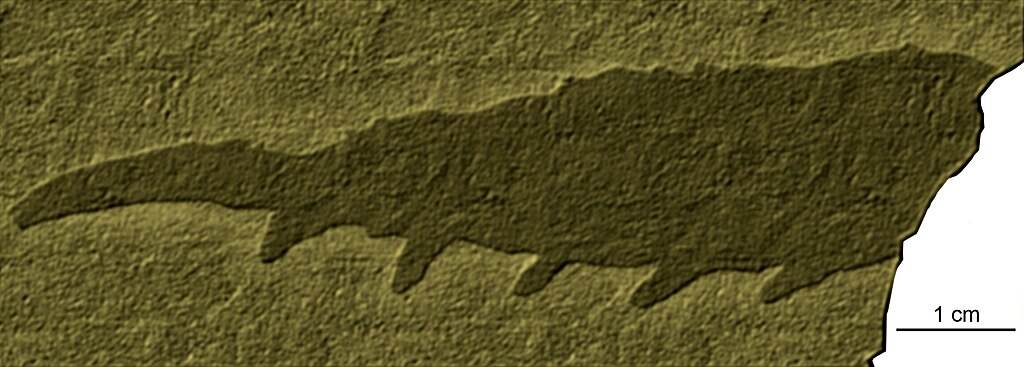

Famous Fossil Finds: The Scipionyx Case Study

One of the most remarkable discoveries in dinosaur dietary research came with the unearthing of Scipionyx samniticus in Italy in 1993, a juvenile theropod with extraordinarily preserved soft tissue, including intestinal contents. This specimen, nicknamed “Scipio,” revealed not just the stomach contents but the actual structure of internal organs, providing unprecedented insights into dinosaur digestion. The stomach contents included fish bones and possibly small reptiles, indicating that this small predator hunted aquatic and semi-aquatic prey. The preservation was so exceptional that scientists could identify different sections of the digestive tract, showing how food was processed from ingestion through elimination. This remarkable fossil demonstrated that young theropods were active hunters rather than scavengers, capable of capturing and consuming prey at a very early age. The Scipionyx discovery revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur physiology and represented a watershed moment in paleontological research into dinosaur diets.

The Brontosaurus Mystery: What Did Sauropods Eat?

The massive sauropods, including Brontosaurus and its relatives, have presented particular challenges for dietary research due to the rarity of preserved stomach contents for these giants. Recent discoveries have revealed conifer needles, seed pods, and ferns in sauropod digestive tracts, confirming their herbivorous nature while suggesting they fed primarily on gymnosperms and pteridophytes. The surprising discovery of charcoal in some sauropod stomach contents indicates they may have fed in recently burned areas, possibly taking advantage of new growth or exposed food sources. Analysis of tooth wear patterns and rare stomach contents reveals that different sauropod species evolved specialized feeding strategies, with some focusing on high-browsing in the canopy while others grazed on lower vegetation. The enormous food requirements of these titans—potentially hundreds of pounds of plant matter daily—meant they likely spent the majority of their waking hours feeding, stripping branches with rake-like teeth and processing vegetation with the help of gastroliths in their muscular gizzards. The efficient digestive systems of sauropods, evidenced by fossilized stomach contents, allowed them to process low-nutrient plant materials and reach their gigantic sizes.

Microstructure Analysis: The Tiny Details of Dinosaur Diets

Advanced microscopic examination of fossilized stomach contents has revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur diets through the analysis of cellular structures preserved for millions of years. Paleontologists using scanning electron microscopy can identify specific plant tissues, distinguishing between woody stem material, leaf fragments, seeds, and reproductive structures in herbivorous dinosaurs. For carnivorous specimens, microstructure analysis reveals details such as feather barbules, scales, or distinctive bone cell patterns that identify prey species that would be unrecognizable to the naked eye. The orientation and degradation of these microstructures provide insights into digestive efficiency, showing which dinosaurs thoroughly processed their food and which relied on fermentation or other digestive strategies. In some exceptionally preserved specimens, scientists have identified pollen grains within stomach contents, offering precise information about the plants consumed and even the season in which the dinosaurs died. These microscopic details help reconstruct ancient food webs with previously impossible precision, transforming our understanding of dinosaur ecology and interspecies relationships within prehistoric ecosystems.

Dietary Changes Through Growth Stages

Fossilized stomach contents from dinosaurs of different ages reveal fascinating shifts in diet throughout their lifespans. Juvenile tyrannosaurs show evidence of having consumed smaller, more agile prey than their adult counterparts, suggesting a shift toward larger prey as they grew in size and strength. Similarly, some herbivorous dinosaurs appear to have consumed softer, more nutrient-rich vegetation when young, transitioning to tougher, more fibrous plant materials as their dental and digestive capabilities matured. These dietary shifts likely reduced competition between juveniles and adults of the same species, allowing different generations to exploit different resources within the same habitat. In some hadrosaur specimens, researchers have found evidence that younger individuals consumed more fruits and seeds, while adults processed greater quantities of woody material, indicating age-related specialization. These ontogenetic dietary shifts parallel those seen in many modern animals, where nutritional needs and physical capabilities change dramatically from birth to adulthood, demonstrating the complex ecological roles dinosaurs played throughout their lives.

Regional and Environmental Variations in Dinosaur Diets

Fossilized stomach contents from the same dinosaur species found in different geographic regions often reveal substantial dietary variations based on local food availability. Hadrosaurs from coastal environments show evidence of having consumed different plant materials than their inland counterparts, suggesting dietary flexibility based on habitat. This dietary adaptability likely contributed to the global success and wide distribution of many dinosaur groups across varied ecosystems. Seasonal variations are also evident in some specimens, with stomach contents reflecting different food resources available during specific times of year, indicating dinosaurs adjusted their feeding habits as environmental conditions changed. Analysis of dinosaur fossils across latitudinal gradients shows that species living in higher latitudes often had different diets than their equatorial relatives, adapting to regional flora and the challenges of seasonal resource availability. These geographic and environmental variations in diet demonstrate that dinosaurs were not rigid in their feeding behaviors but rather displayed ecological plasticity that helped them thrive across the supercontinent Pangaea and later, as the continents began to separate during the Mesozoic Era.

Cannibalism and Unusual Feeding Behaviors

Perhaps some of the most surprising discoveries in fossilized stomach contents involve evidence of cannibalism among certain dinosaur species. Several theropod specimens have been found with the remains of smaller individuals of the same species in their digestive tracts, suggesting opportunistic cannibalistic behavior during times of resource scarcity or perhaps as a form of population control. Beyond cannibalism, unusual items found in dinosaur stomachs include small mammals, eggs of other species, and in one remarkable case, a pterosaur, indicating that dinosaurs sometimes consumed prey or food items outside their typical dietary range. These unexpected findings challenge simplified notions of dinosaur feeding behavior and reveal the complexity of prehistoric food webs. Some specimens show evidence of selective feeding on specific organs or body parts of prey, suggesting sophisticated hunting strategies rather than indiscriminate consumption. The discovery of marine organisms in the stomachs of predominantly terrestrial dinosaurs indicates that some species opportunistically foraged along shorelines or in shallow waters, demonstrating behavioral flexibility that likely contributed to their evolutionary success across diverse habitats.

Implications for Dinosaur Physiology and Metabolism

The examination of fossilized stomach contents provides crucial insights into dinosaur metabolism and physiology, helping resolve long-standing debates about whether these creatures were cold-blooded like modern reptiles or warm-blooded like birds and mammals. The quantity and type of food found in carnivorous dinosaur stomachs suggest high metabolic rates requiring substantial caloric intake, supporting theories that many dinosaurs maintained elevated body temperatures. For herbivorous dinosaurs, the discovery of extensive plant processing adaptations, including gastroliths and fermentation chambers evidenced by partially decomposed plant materials, indicates complex digestive systems that efficiently extracted nutrients from fibrous vegetation. The presence of highly processed food in the intestinal regions of some specimens suggests lengthy digestion times, which aligns with the massive food requirements of larger dinosaurs. Some discoveries reveal seasonal variation in food consumption, indicating dinosaurs may have adjusted their metabolic rates during different environmental conditions, similar to some modern animals. These physiological insights help explain how dinosaurs could maintain their often enormous body sizes and high activity levels across the various climatic conditions they encountered during their 165-million-year reign.

Future Frontiers in Dinosaur Diet Research

The field of dinosaur dietary research stands at an exciting frontier, with new technologies promising unprecedented insights from fossilized stomach contents in the coming decades. Advanced chemical analysis techniques, including organic compound identification and molecular paleontology, may soon allow scientists to identify specific proteins and other biomolecules preserved in dinosaur gut contents, revealing details about their diets undetectable through conventional methods. The application of artificial intelligence to analyze complex patterns in fossilized stomach contents could help identify previously overlooked dietary components and patterns across species. Non-destructive imaging technologies continue to advance, allowing paleontologists to examine stomach contents still embedded in rock matrices without damaging precious specimens. Comparative studies incorporating modern animals’ digestive processes may help scientists better interpret the fossilized evidence, creating more accurate models of dinosaur digestion and metabolism. As new specimens are discovered in previously unexplored regions of the world, our understanding of dinosaur dietary diversity will continue to expand, potentially revealing specialized feeding adaptations unique to different geographic areas and evolutionary lineages.

Conclusion: What Dinosaur Diets Tell Us About Prehistoric Ecosystems

Fossilized stomach contents serve as time capsules that illuminate not just what individual dinosaurs ate but the complex relationships that structured entire Mesozoic ecosystems. These precious specimens reveal intricate food webs connecting plants, herbivores, omnivores, and carnivores in relationships that sustained biodiversity for millions of years. The specificity of many dinosaurs’ diets, evidenced by their stomach contents, demonstrates sophisticated niche partitioning that allowed multiple species to coexist by utilizing different food resources within the same habitats. The evolution of specialized feeding strategies visible in the fossil record tracks alongside environmental changes throughout the Mesozoic, showing how dinosaurs adapted to shifting climates and plant communities over time. As research techniques continue to advance, each discovery of fossilized stomach contents adds another piece to our understanding of how these remarkable animals lived, interacted, and ultimately dominated Earth’s terrestrial ecosystems for longer than any other vertebrate group in our planet’s history. Through these dietary snapshots frozen in time, we continue to develop a more nuanced and complete picture of dinosaurs not as monsters or movie villains but as living animals intricately connected to their environments and to each other.