When we imagine dinosaurs, we often picture ferocious predators like Tyrannosaurus rex tearing into prey. However, the reality of dinosaur diets was far more diverse and fascinating. Approximately 65% of all dinosaur species were herbivores, consuming various types of prehistoric plants throughout the Mesozoic Era (252-66 million years ago). Understanding what plant-eating dinosaurs consumed requires examining both the anatomy of these dinosaurs and the plants that populated their world. This journey through ancient dietary habits reveals a complex relationship between prehistoric creatures and their botanical food sources that helped shape Earth’s ecosystems for millions of years.

The Prehistoric Plant World: Not Your Modern Garden

The plant kingdom during the dinosaur age looked remarkably different from today’s flora. During the Mesozoic Era, flowering plants (angiosperms) had not yet dominated the landscape as they do now. Instead, the world was covered with vast forests of gymnosperms like conifers, cycads, ginkgoes, and seed ferns. These plants lacked the flowers and fruits familiar to us and reproduced primarily through cones and exposed seeds. Ferns and horsetails carpeted the forest floors, while towering tree ferns created dense canopies in many regions. The absence of grasses is particularly notable – the lush meadows we associate with grazing animals didn’t exist for most of dinosaur history, with true grasses only appearing in the Late Cretaceous period, toward the end of dinosaur dominance.

Dental Details: How Teeth Reveal Dinosaur Diets

Paleontologists learn tremendous amounts about dinosaur diets by studying their fossilized teeth. Herbivorous dinosaurs typically had teeth specialized for processing tough plant material – either broad, leaf-shaped teeth for snipping vegetation or batteries of small, tightly-packed teeth for grinding tough plant material. Sauropods like Brachiosaurus had peg-like teeth perfect for stripping leaves, but did minimal chewing, relying instead on gastroliths (stomach stones) and lengthy digestive systems to break down plant matter. In contrast, ornithischian dinosaurs like Triceratops had complex dental batteries that allowed them to thoroughly chew fibrous plants before swallowing. The varying dental adaptations among different dinosaur groups indicate specialization for different types of plant food, much like we see in modern herbivores.

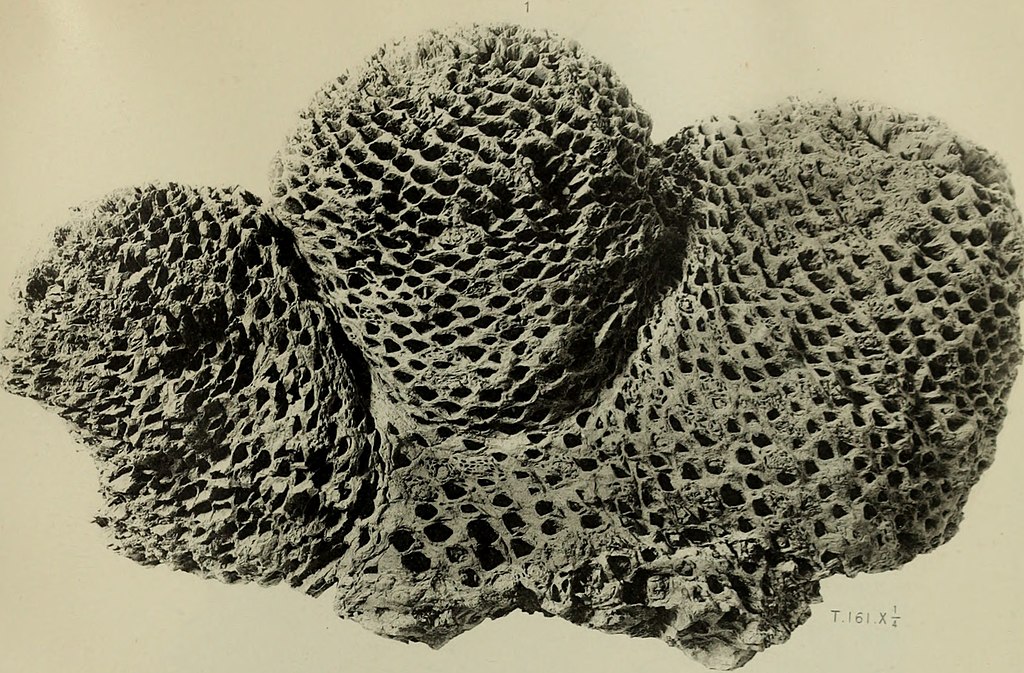

The Cycad Conundrum: Dinosaur Delicacies or Toxic Temptations?

Cycads were particularly abundant during the Mesozoic and resembled modern palm trees, though they’re not closely related. These plants produce large, nutrient-rich seeds and have been traditionally viewed as important dinosaur food sources. However, modern cycads contain high levels of neurotoxins that make them dangerous to consume for most animals, raising questions about their role in dinosaur diets. Some paleobotanists theorize that Mesozoic cycads may have been less toxic than their modern descendants, while others propose that dinosaurs might have developed specialized digestive systems to detoxify these compounds. Evidence from coprolites (fossilized dung) has shown cycad remains, suggesting that at least some dinosaur species did indeed consume these plants, perhaps in moderation or during specific growth phases when toxicity was lower.

The Rise of Flowers: How Angiosperms Changed Dinosaur Diets

The Cretaceous Period witnessed a revolutionary botanical development – the emergence and rapid diversification of flowering plants (angiosperms). This dramatic shift in plant communities likely influenced dinosaur evolution and eating habits. As flowering plants spread across landscapes, offering new nutritional profiles and reproductive strategies, certain dinosaur groups appear to have adapted to take advantage of these resources. Some ornithopods and ceratopsians developed more sophisticated jaws and teeth that could better process angiosperm vegetation. Microscopic wear patterns on fossilized teeth suggest that certain hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) had shifted to incorporate significant amounts of flowering plants in their diets by the Late Cretaceous. This coevolutionary relationship between dinosaurs and flowering plants represents one of the most important ecological developments of the Mesozoic Era.

Tiny Leaves, Massive Appetites: Feeding the Sauropod Giants

The enormous sauropod dinosaurs present a fascinating dietary puzzle. These giants, some weighing upward of 70 tons, required massive amounts of plant material daily, potentially hundreds of pounds, yet had relatively small heads and mouths compared to their body size. Research suggests they employed a feeding strategy that maximized intake while minimizing energy expenditure. Rather than thoroughly chewing food, sauropods likely stripped leaves and branch tips from trees using their peg-like teeth and swallowed them largely intact. Their extraordinarily long necks allowed them to reach vegetation at various heights without moving their massive bodies. Once ingested, plant material would spend days in their enormous digestive systems, where bacteria broke down tough plant fibers. This feeding strategy allowed sauropods to process enormous quantities of relatively low-quality plant matter efficiently.

Fern Fever: The Importance of Pteridophytes in Dinosaur Diets

Ferns and their relatives (collectively called pteridophytes) represented crucial components of many dinosaur diets, particularly for low-browsing species. These spore-producing plants existed in tremendous diversity during the Mesozoic, from tiny ground-covering varieties to massive tree ferns reaching heights of 20 feet or more. Analysis of coprolites has revealed fern spores in the digestive remains of numerous herbivorous dinosaurs, indicating widespread consumption. Some smaller ornithopods appear to have specialized in fern consumption, with dental structures particularly well-suited for clipping fern fronds. Ferns typically contain higher protein levels than many other plant groups, making them nutritionally valuable, though they also contain various chemical defenses. The relationship between ferns and dinosaurs likely drove evolutionary adaptations on both sides – ferns developing stronger chemical deterrents while dinosaurs evolved mechanisms to process or neutralize these compounds.

Conifers: The Backbone of Mesozoic Forests and Dinosaur Nutrition

Coniferous plants dominated many Mesozoic landscapes, providing essential food resources for numerous dinosaur species. These gymnosperms – including ancient relatives of modern pines, redwoods, and yews – offered a variety of edible parts beyond just their needles. Many herbivorous dinosaurs likely consumed young, tender conifer shoots, which contain higher nutrient levels and fewer defensive compounds than mature needles. Fossil evidence suggests that some ornithischians targeted conifer cones for their nutrient-rich seeds. The toughness of mature conifer vegetation potentially drove some of the most extreme adaptations seen in dinosaur skulls and teeth, particularly in ceratopsians and hadrosaurs, whose powerful jaws and dental batteries could efficiently process this fibrous material. Analysis of preserved stomach contents from exceptional fossils has confirmed conifer consumption in several dinosaur species, solidifying their importance in Mesozoic food webs.

Horsetails and Ginkgoes: Overlooked Elements of Dinosaur Diets

Beyond the more prominent plant groups, horsetails (Equisetales) and ginkgoes represent often-overlooked components of dinosaur nutrition. Horsetails, which grew much larger in the Mesozoic than their modern descendants, provided abundant, easily digestible vegetation in wetland environments frequently inhabited by dinosaurs. These plants have high silica content and leave distinctive microscopic wear patterns on teeth, allowing paleontologists to identify horsetail consumers. Ginkgo trees, represented today by only one species but diverse during the dinosaur era, produced nutritious seeds and relatively soft leaves compared to conifers. Remarkably, modern ginkgo trees retain defensive compounds that may have evolved specifically to deter dinosaur browsing. Chemical analysis of preserved ginkgo fossils from the Mesozoic shows evidence of these same compounds, suggesting an evolutionary arms race between these trees and their dinosaur consumers that persisted for millions of years.

Stomach Stones: The Dinosaur’s Secret Digestive Tool

Many herbivorous dinosaurs employed a fascinating digestive adaptation: gastroliths, or stomach stones. These polished rocks, sometimes found with dinosaur skeletons, were intentionally swallowed and retained in the digestive tract. Inside a specialized stomach chamber, these stones would grind against plant material, mechanically breaking it down much like the gizzard in modern birds. This adaptation proved particularly important for sauropods and other dinosaurs that lacked sophisticated chewing teeth. By essentially “chewing” food in their stomachs, these dinosaurs could process tough plant material more efficiently despite anatomical limitations in their jaws. Experimental studies with modern birds have shown that gastroliths significantly improve the breakdown of fibrous plant material, increasing nutritional extraction by up to 30 percent. The size, quantity, and composition of gastroliths varied between different dinosaur species, likely reflecting their specific dietary needs and the types of vegetation they consumed.

Chemical Warfare: Plant Defenses vs. Dinosaur Digestive Systems

The relationship between plants and herbivorous dinosaurs represented a classic evolutionary arms race, with plants developing increasingly sophisticated chemical defenses while dinosaurs evolved countermeasures. Modern plants produce thousands of secondary compounds – tannins, alkaloids, terpenes, and other chemicals – specifically to deter herbivores, and evidence suggests Mesozoic plants employed similar strategies. Plant fossils from the dinosaur era show structural adaptations associated with chemical defense, such as specialized secretory canals and glands. Dinosaurs likely developed various physiological adaptations to counter these toxins, potentially including specialized gut bacteria that could detoxify harmful compounds. The massive size of many herbivorous dinosaurs may itself have been partly an adaptation to plant toxins, as larger bodies can better dilute and process defensive chemicals. This chemical battlefield between plants and dinosaurs drove significant evolutionary innovations on both sides, helping shape the diversity of both groups.

Seasonal Shifts: How Dinosaur Diets Changed Throughout the Year

Unlike the relatively stable year-round vegetation patterns in modern tropical regions, many dinosaurs experienced significant seasonal variations in their food supply. During the Mesozoic, even regions near the equator experienced distinct wet and dry seasons that affected plant growth patterns. Evidence from growth rings in fossil plants and bones suggests that dinosaurs faced seasonal challenges in maintaining adequate nutrition. Many herbivorous dinosaurs likely altered their diets seasonally, focusing on different plant species or plant parts as availability changed. Some paleontologists theorize that certain dinosaur migrations may have been driven by these seasonal shifts in vegetation. Analysis of dental microwear in some species shows patterns suggesting dietary changes throughout the year – worn teeth from one season show different abrasion patterns than those from another, indicating consumption of different plant types. This dietary flexibility likely represented a crucial survival strategy for many herbivorous dinosaurs.

The Digestive Timeline: How Plant Processing Evolved Across Dinosaur History

Over the 165 million years of dinosaur evolution, herbivore digestive strategies underwent significant transformations. Early ornithischians from the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic had relatively simple dental arrangements and likely processed vegetation minimally before swallowing. By the mid-Jurassic, more advanced chewing mechanisms had evolved, particularly in stegosaurs and early ornithopods, allowing more efficient extraction of nutrients from plant tissues. The Late Cretaceous saw the pinnacle of dinosaur digestive adaptations, with hadrosaurs and ceratopsians developing remarkably complex dental batteries capable of thoroughly grinding even the toughest plant materials. Different dinosaur lineages independently evolved various solutions to the challenge of plant digestion. Sauropods relied on extremely long residence times in their massive digestive tracts, while ceratopsians developed some of the most powerful bite forces of any herbivores in Earth’s history. This progressive refinement of plant-processing abilities allowed dinosaurs to exploit increasingly diverse plant resources throughout their reign.

From Fossils to Food Webs: Reconstructing Complete Dinosaur Diets

Modern paleontologists employ multiple lines of evidence to build comprehensive pictures of dinosaur diets. Beyond traditional anatomical studies of teeth and jaws, researchers now analyze microscopic tooth wear patterns that reveal specific plant textures processed during an animal’s final months of life. Chemical analysis of fossilized bones provides isotopic signatures that can distinguish between the consumption of different plant types. Rare fossilized stomach contents offer direct evidence of specific meals, while coprolites provide insights into digestion efficiency and food preferences. Computer modeling of jaw mechanics allows scientists to calculate bite forces and chewing capabilities with unprecedented accuracy. When combined with detailed studies of contemporaneous plant fossils, these approaches allow for increasingly sophisticated dietary reconstructions. The emerging picture reveals that dinosaur herbivory was not a simple matter of indiscriminate plant consumption but involved complex specializations and ecological relationships. Each herbivorous dinosaur species likely occupied a specific dietary niche, targeting particular plants and plant parts that they were uniquely adapted to process.

Exploring What Dinosaurs Ate and Their Ancient Plant Diets

The story of what dinosaurs ate reveals an intricate dance between plant evolution and dinosaur adaptation that spanned millions of years. From the towering sauropods browsing high in conifer canopies to ceratopsians grinding tough cycad fronds with their powerful jaws, herbivorous dinosaurs developed remarkable specializations to exploit the plant resources of their time. As our understanding of both ancient plants and dinosaur physiology continues to improve, we gain deeper insights into the ecological relationships that shaped the Mesozoic world. These prehistoric dietary connections didn’t simply disappear with the dinosaurs – they laid the groundwork for the plant-herbivore relationships we see today. The next time you picture a dinosaur, look beyond the fearsome predators to the equally fascinating plant-eaters, whose daily quest for vegetation helped drive some of the most important evolutionary innovations in Earth’s history.