Picture the morning after the most catastrophic day in Earth’s history. The asteroid had already made its mark, a chunk of extraterrestrial rock over 6 miles wide slammed into what would eventually become known as Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. The shock was a planet-scale version of a gunshot. This wasn’t just another geological event, it was the beginning of an entirely new chapter for life on our planet.

The devastation was beyond imagination, yet somehow life would find a way to continue. What followed that terrible day would set the stage for the rise of mammals, the emergence of modern ecosystems, and ultimately, the world we know today. Let’s journey back to witness what Earth looked like during those first critical hours and days after the dinosaurs vanished forever.

A World Transformed by Fire and Darkness

The immediate aftermath was like something from a nightmare. When the asteroid plowed into the Earth, tiny particles of rock and other debris were shot high into the air. Geologists have found these bits, called spherules, in a 1/10-inch-thick layer all around the world. These weren’t just ordinary particles, they became instruments of global destruction.

The kinetic energy carried by these spherules is colossal, about 20 million megatons total or about the energy of a one megaton hydrogen bomb at six kilometer intervals around the planet. All of that energy was converted to heat as those spherules started to descend through the atmosphere 40 miles up, about 40 minutes after impact. Picture billions of incandescent torches falling from the sky, turning the entire planet into a furnace.

The First Hours: A Planet on Fire

For several hours following the Chicxulub impact, the entire Earth was bathed with intense infrared radiation from ballistically reentering ejecta. Earth became a world on fire. Nothing could escape this global inferno. Any creature not underground or not underwater – that is, most dinosaurs and many other terrestrial organisms – could not have escaped it.

The heat was so intense that it ignited forests thousands of miles from the impact site. The impact event ignited trees and plants that were thousands of miles away, and triggered a massive tsunami, as deep as the ocean and travelling at supersonic speeds, that reached as far inland as Illinois, 2,000km away. Those few creatures that managed to survive the initial blast found themselves in an alien landscape of ash and fire.

The Darkness That Followed

If the fire wasn’t enough, something even more sinister was taking hold. Clouds of pulverized rock and sulfuric acid from the crash would have darkened skies, cooled global temperatures, produced acid rain and sparked wildfires. The once bright blue sky turned into a suffocating blanket of dust and debris.

The prevailing dimness caused by the dust cloud meant photosynthesis would have been dramatically reduced. Plants, the foundation of most food chains, began to die en masse. The soot and ash would have taken months to wash out of the atmosphere, and when it did, the rain would have fallen as acidic mud. This wasn’t just an extinction, it was the complete breakdown of Earth’s life support systems.

Immediate Casualties: The Great Dying

The scope of destruction was staggering. The available fossil record shows that about 75 percent of known species completely disappeared, and things probably weren’t rosy for the survivors. It’s reasonable to suppose that the 25 percent of surviving species had near-total mortality, but these fortunate organisms were the ones that would go on to set the stage for the next 66 million years of evolutionary history.

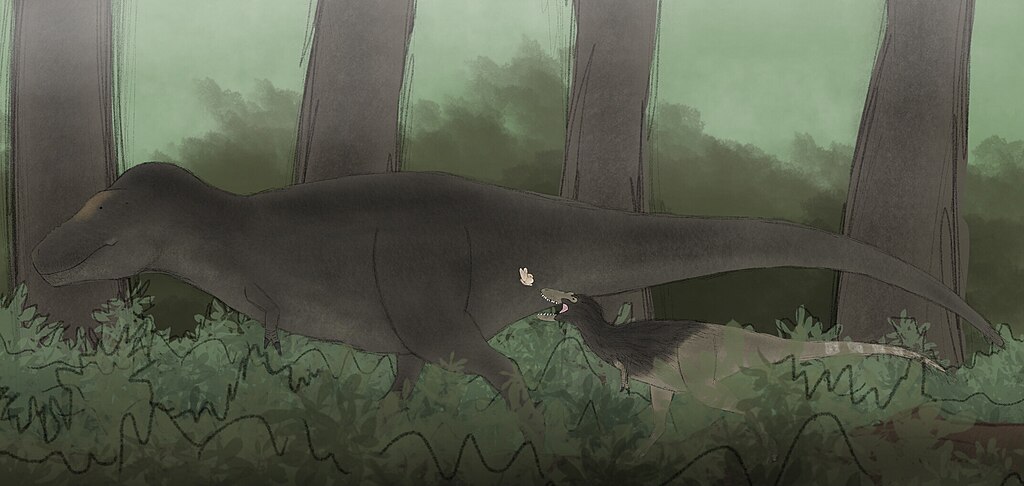

The dinosaurs, who had ruled the Earth for over 170 million years, were among the first to go. The event caused the extinction of all non-avian dinosaurs. Most other tetrapods weighing more than 25 kg (55 lb) also became extinct, with the exception of some ectothermic species such as sea turtles and crocodilians. The age of giants was over, replaced by a world of small survivors.

Rebuilding From the Ashes: The First Signs of Recovery

Yet even in this devastation, life began to stir. Terrestrial Paleocene strata immediately overlying the K-T boundary is, in places, marked by a “fern spike:” a bed especially rich in fern fossils. Ferns are often the first species to colonize areas damaged by forest fires; thus the fern spike may indicate post-Chicxulub devastation. Like nature’s first responders, ferns began to reclaim the scorched earth.

Remarkably, within just a few years, life returned to the submerged impact crater, according to a new analysis of sediments in the crater. Tiny marine creatures flourished thanks to the circulation of nutrient-rich water. Even at ground zero of the apocalypse, life was already planning its comeback.

The Survivors: Who Made It Through

The creatures that survived had specific advantages. K–Pg boundary mammalian species were generally small, comparable in size to rats; this small size would have helped them find shelter in protected environments. It is postulated that some early monotremes, marsupials, and placentals were semiaquatic or burrowing, as there are multiple mammalian lineages with such habits today. Any burrowing or semiaquatic mammal would have had additional protection from K–Pg boundary environmental stresses.

Birds also survived, though drastically reduced in number. Only a small fraction of ground and water-dwelling Cretaceous bird species survived the impact, giving rise to today’s birds. These survivors would become the foundation for entirely new evolutionary branches.

The Dawn of the Paleocene: A New World Emerges

The Paleocene Epoch is the 10 million year time interval directly after the K–Pg extinction event, which ended the Cretaceous Period and the Mesozoic Era, and initiated the Cenozoic Era and the Paleogene Period. This marked the official beginning of our current geological era, though the Earth that emerged was radically different from what came before.

The K–Pg extinction event caused a floral and faunal turnover of species, with previously abundant species being replaced by previously uncommon ones. In the absence of large dinosaurian herbivores, the extinction of large herbivorous dinosaurs may have allowed the forests to grow quite dense, and there is little evidence of wide open plains. Earth was becoming a world of forests once again.

Conclusion: The Day That Changed Everything

, Earth was a planet in ruins, yet it was also a world of infinite possibility. The extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous Period opened numerous ecological niches. These were filled mostly by mammals, which underwent a dramatic evolutionary radiation. From the ashes of that terrible day rose the ancestors of whales, primates, and countless other creatures that would shape the modern world.

Looking back at that catastrophic moment 66 million years ago, it’s humbling to realize that our own existence traces back to those small, furry survivors huddled in burrows and hiding places. What do you think about this incredible transformation? Tell us in the comments.