The history of life on Earth remains one of our most fascinating scientific narratives, with dinosaurs occupying a particularly special place in our collective imagination. For over 165 million years, these magnificent creatures dominated terrestrial ecosystems across the globe. But what if the fossil record we have today represents only a fraction of dinosaur diversity? What if entire dinosaur civilizations evolved on landmasses that no longer exist—continents that have since disappeared beneath the waves? This article explores this tantalizing hypothetical scenario, examining the scientific possibilities, geological realities, and what we might be missing in our understanding of prehistoric life.

The Geological Reality of Lost Continents

While popular culture sometimes references mythical sunken lands like Atlantis or Lemuria, geology does recognize several actual “lost continents” or significant landmasses that have disappeared beneath the oceans. Most notably, Zealandia—a continent that is 94% submerged beneath the Pacific Ocean with only New Zealand and New Caledonia remaining above water—represents a genuine sunken landmass. Other examples include the microcontinent of Mauritia in the Indian Ocean and several now-submerged continental shelves that were exposed during periods of lower sea levels. These lost landmasses didn’t simply sink dramatically like in disaster movies; rather, they underwent complex geological processes including crustal thinning, subsidence, and flooding over millions of years. The geological record confirms that throughout Earth’s history, the configuration of continents has changed dramatically due to plate tectonics, with landmasses appearing and disappearing from the surface.

Mechanisms of Continental Submergence

Continental submergence occurs through several geological mechanisms, none of which involve sudden catastrophic sinking like popular myths suggest. The primary process is crustal thinning, where continental crust stretches and becomes thinner during tectonic rifting events, causing the land surface to subside gradually. Sea level changes also play a crucial role, with global sea levels fluctuating by hundreds of meters throughout Earth’s history due to factors like ice age cycles and changes in ocean basin volume. During the dinosaur era, sea levels were generally much higher than today, with Cretaceous levels potentially 100-200 meters above present, flooding vast continental areas. Post-glacial rebound and isostatic adjustment represent additional factors where land rises or sinks in response to the weight of ice sheets or sediment accumulation. Finally, continental margins can experience thermal subsidence, gradually sinking as they cool and contract after initial formation, resulting in formerly exposed lands becoming permanently submerged.

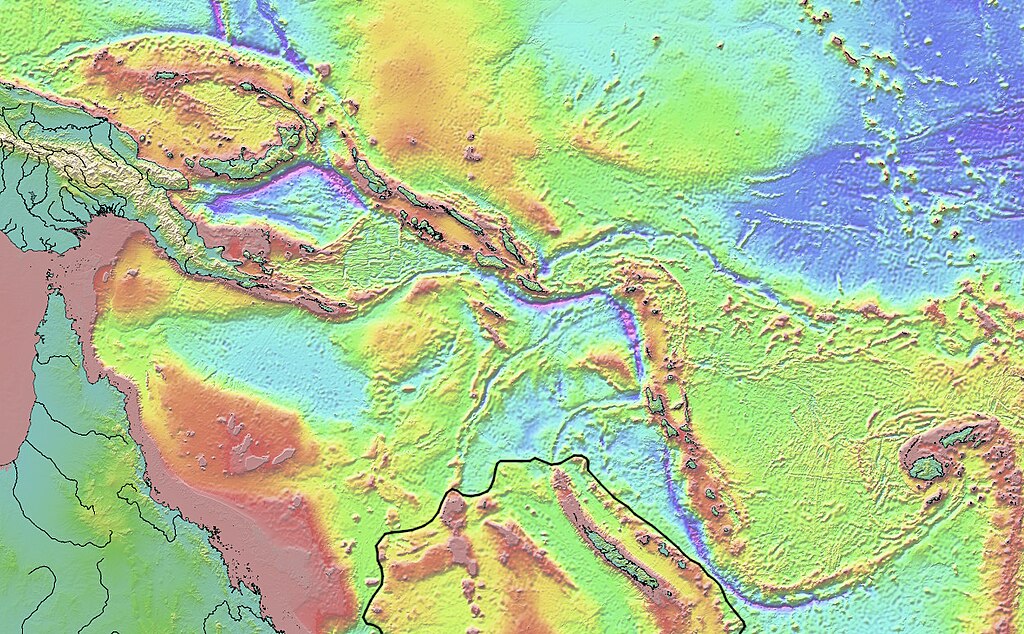

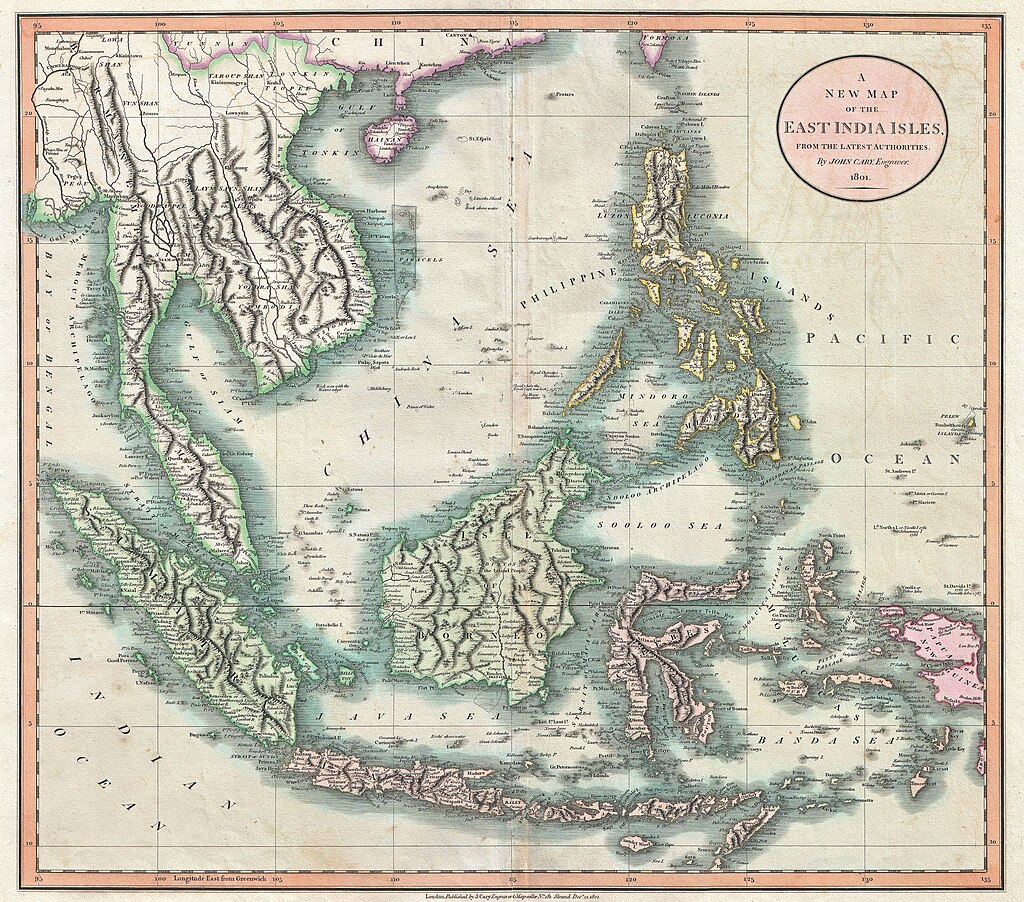

Known Submerged Paleoenvironments

Geological evidence confirms numerous once-terrestrial environments now lie beneath the oceans, potentially with their own unique dinosaur fossils. The North Sea basin between Great Britain and continental Europe was largely dry land during the Mesozoic era, hosting dinosaur communities whose traces are occasionally recovered from drilling operations. The Sundaland region of Southeast Asia represented a vast continuous landmass during periods of lower sea levels, connecting what are now separate islands like Borneo, Java, and Sumatra. The Kerguelen Plateau in the southern Indian Ocean was partially above water during the Cretaceous period, potentially supporting distinct dinosaur populations in an area now entirely underwater. The continental shelves surrounding most modern landmasses extended much further during dinosaur times, creating vast coastal plains that would have supported unique ecosystems. These submerged environments represent significant “missing pieces” in our understanding of dinosaur biogeography and evolution.

Dinosaur Biogeography and Continental Distribution

The distribution of dinosaur species across different landmasses followed complex patterns influenced by continental positioning, climate zones, and evolutionary pressures. During the early Mesozoic, when most continents were united in the supercontinent Pangaea, dinosaur groups showed relatively similar compositions worldwide. As Pangaea fragmented through the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, dinosaur populations became increasingly isolated, developing distinctive regional characteristics. The fossil record reveals clear biogeographic provinces by the Late Cretaceous, with unique dinosaur assemblages evolving in separate continental regions like North America, South America, Asia, and Africa. These patterns suggest that any now-submerged continents would likely have developed their own distinctive dinosaur faunas, particularly if they experienced significant isolation. The longer a landmass remained isolated, the more divergent and unique its dinosaur population would have become, potentially leading to entirely novel evolutionary lines not represented in our current fossil record.

The Possible Sunken Dinosaur Civilizations of Zealandia

Zealandia represents our most compelling example of a sunken continent that almost certainly hosted unique dinosaur species during the Mesozoic era. This nearly New Zealand-sized landmass was largely above water during dinosaur times, becoming progressively submerged over the past 80 million years. The limited terrestrial exposures in modern New Zealand have yielded tantalizing dinosaur fossils, including evidence of unique theropods, sauropods, and ornithischians adapted to life in this southern continent. Given Zealandia’s isolation from other major landmasses after the breakup of Gondwana, it likely developed a highly specialized dinosaur fauna with distinctive adaptations and evolutionary trajectories. Paleontologists speculate that the continent may have harbored dwarf forms of larger dinosaur groups, unique flightless birds, and specialized forest-adapted species suited to its temperate rainforest environments. The full diversity of Zealandia’s dinosaur communities remains largely hypothetical, with the vast majority of potential fossil-bearing strata now lying hundreds of meters beneath the Pacific Ocean.

Microcontinent Mauritia and the Dinosaurs of the Indian Ocean

The relatively recently discovered microcontinent of Mauritia, now mostly submerged beneath the Indian Ocean between Madagascar and India, represents another potential lost world of dinosaur evolution. Geological evidence suggests this continental fragment remained above water during significant portions of the Mesozoic era as India separated from Madagascar and Africa during the breakup of Gondwana. Given its position along a crucial migration corridor between major landmasses, Mauritia may have hosted important transitional dinosaur faunas containing elements from both African and Indo-Madagascan evolutionary lines. The few exposed portions of this former microcontinent, including Mauritius and Réunion islands, consist primarily of much younger volcanic materials overlying the ancient continental crust, meaning any dinosaur fossils remain deeply buried or submerged. Paleontologists speculate that as a relatively small, isolated landmass, Mauritia may have experienced pronounced island effects on its dinosaur populations, potentially hosting dwarf forms of larger dinosaurs and unusual adaptive radiations in response to limited resources.

Hypothetical Evolutionary Trajectories

Had dinosaurs evolved on now-submerged continents in isolation, they would likely have followed distinctive evolutionary pathways not represented in our current fossil record. Isolation drives speciation and novel adaptations, as demonstrated by the unique fauna that evolved on island continents like Australia and Madagascar. On sunken landmasses with different climate regimes or ecological pressures, dinosaur groups might have developed body plans and adaptations entirely unknown to paleontology. Small isolated continents might have driven miniaturization in typically large dinosaur groups, while unique predator-prey dynamics could have resulted in novel defensive or predatory adaptations. The complex interaction between geological processes, climate changes, and biological evolution would have shaped these dinosaur populations in ways we can only theoretically model. Given the extraordinary diversity and adaptability demonstrated by known dinosaur fossils, the range of possible forms that might have evolved on lost continents staggers the imagination, from specialized marine-adapted coastal species to highly derived arboreal forms in isolated forest ecosystems.

The Fossil Record Gap

The submergence of formerly terrestrial environments creates significant gaps in our understanding of dinosaur evolution and diversity. While terrestrial fossils can occasionally form in underwater settings, the process of continental submergence typically subjects fossil-bearing rocks to erosion, chemical breakdown, and physical destruction. Marine sediments eventually cover these formations, placing potential dinosaur-bearing strata hundreds or thousands of meters below the modern ocean floor. The technological challenges of accessing these deposits mean they remain largely unexplored by paleontologists, creating what scientists call “sampling bias” in the fossil record. This bias particularly affects our understanding of island and coastal ecosystems, which are disproportionately affected by sea level changes and marine transgression. The areas most likely to contain fossils from unique isolated dinosaur populations—island continents and microcontinents—are precisely those most vulnerable to submergence and loss from the accessible fossil record.

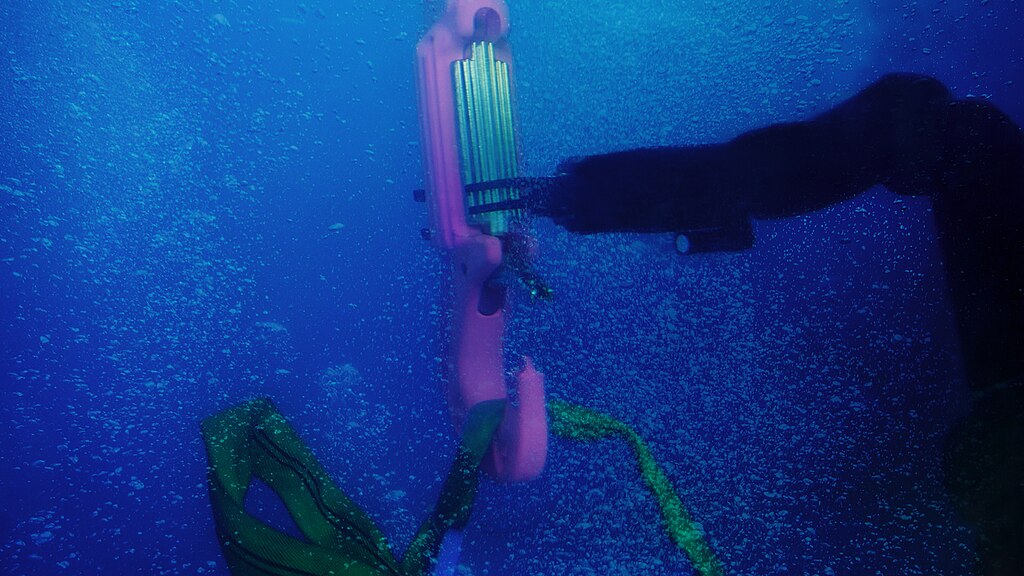

Modern Technology and Submarine Paleontology

Recent technological advances offer tantalizing possibilities for someday accessing dinosaur fossils from submerged continental regions. Deep-sea drilling operations occasionally recover sediment cores containing terrestrial materials, though these operations are primarily conducted for resource exploration rather than paleontology. Advanced seismic imaging techniques can now identify potential fossil-bearing formations beneath the seabed, allowing more targeted exploration efforts. Robotic submersibles equipped with sampling tools can investigate submarine outcrops where ancient terrestrial layers might be exposed on deep ocean slopes or in submarine canyons. As offshore wind farm construction and underwater infrastructure projects increase, incidental discovery of submarine fossils becomes more likely, similar to how construction projects on land frequently uncover paleontological treasures. Though the challenges remain formidable, these technologies suggest future generations of paleontologists might directly study the dinosaur communities of currently inaccessible submerged continents.

Case Study: The Western Interior Seaway

While not a fully submerged continent, North America’s Western Interior Seaway provides a valuable analog for understanding how marine transgression affects dinosaur habitats and fossil preservation. During the Cretaceous period, a vast inland sea divided North America into two separate landmasses, creating distinct eastern and western dinosaur provinces with increasingly divergent evolutionary trajectories. The seaway repeatedly expanded and contracted, alternately submerging and exposing large areas of dinosaur habitat over millions of years. Fossil evidence from the boundaries of this ancient seaway shows how coastal dinosaur communities adapted to changing environments, with certain species specializing in these dynamic shoreline habitats. The excellent preservation conditions in these settings have gifted paleontologists with remarkable fossils that might hint at what we could discover from other, more permanently submerged regions. The Western Interior Seaway example demonstrates how sea level fluctuations create complex patterns of habitat fragmentation and reconnection, driving evolutionary diversification in dinosaur populations.

Implications for Dinosaur Diversity Estimates

The existence of now-inaccessible dinosaur-bearing formations on submerged continents significantly impacts our understanding of prehistoric biodiversity. Current estimates suggest paleontologists have identified less than 1% of all dinosaur species that ever lived, with the fossil record capturing only a tiny fraction of ancient life. If substantial landmasses with unique dinosaur communities existed and are now permanently submerged, actual dinosaur diversity could greatly exceed even the most generous current estimates. The question extends beyond simply adding more species to our catalogs—entirely unique evolutionary lineages, body plans, and ecological adaptations may remain completely unknown to science. This “hidden diversity” would particularly affect our understanding of island endemism, where unique species evolve in isolation, as island environments are disproportionately vulnerable to submergence. Recognizing these knowledge gaps has led some paleontologists to employ statistical methods that attempt to account for missing data when reconstructing patterns of dinosaur evolution and extinction.

Extinction Patterns and Survival Possibilities

The gradual submergence of dinosaur-bearing continents would have created fascinating extinction patterns distinct from the sudden Chicxulub impact that ended the Mesozoic era. As sea levels rose and habitats contracted, dinosaur populations would face increasing ecological pressure, with more specialized forms typically disappearing first as generalists adapted to shrinking territories. Island continents undergoing submergence would essentially create a long-term natural experiment in extinction dynamics, potentially selecting for smaller-bodied species with lower resource requirements. The fossil record shows that isolated dinosaur populations often evolved distinct survival adaptations, raising the intriguing possibility that unique evolutionary solutions might have emerged on these lost landmasses. Some paleontologists have even speculated whether certain isolated dinosaur populations might have survived longer than their continental counterparts, persisting on shrinking islands into the early Cenozoic before their habitats finally disappeared beneath the waves, though no conclusive evidence for this scenario has been discovered.

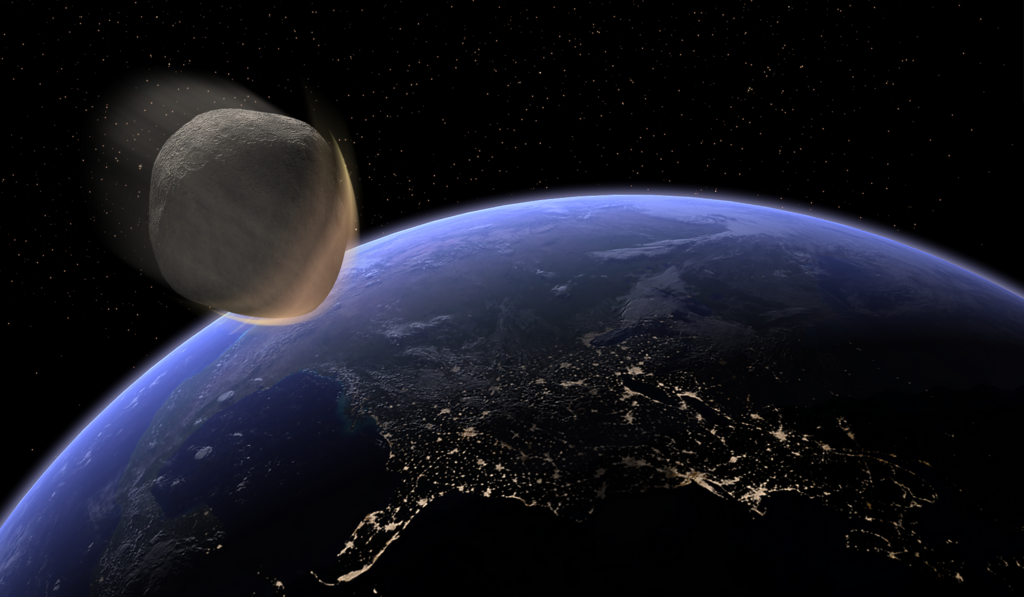

The Science Fiction Versus Scientific Reality

While the concept of lost dinosaur worlds evokes dramatic science fiction scenarios like “The Lost World” or “King Kong,” the geological reality would have been far more gradual and less cinematic. Continental submergence occurs over millions of years, not in sudden catastrophic events, giving animal populations time to adapt, migrate, or gradually decline. The notion that dinosaur species might have survived extinction on isolated islands that later sank makes for compelling fiction but contradicts our understanding of Earth’s history and the global nature of the end-Cretaceous extinction event. Scientists can confidently state that no non-avian dinosaurs survived into the modern era, regardless of where they evolved. However, the scientific reality—that unique evolutionary experiments played out on now-inaccessible terrains—remains almost as fascinating as fiction. The true “lost worlds” of dinosaur evolution represent not living prehistoric animals but rather the countless extinct species whose remains lie permanently beyond our reach beneath the ocean floor.

Conclusion

The possibility that unique dinosaur communities once thrived on now-submerged continents represents one of paleontology’s most tantalizing unknowns. While we may never recover fossils from these hypothetical lost ecosystems, geological evidence confirms that significant landmasses have indeed disappeared beneath the waves since the Mesozoic era. These sunken territories almost certainly hosted dinosaur populations that evolved in partial or complete isolation, potentially developing forms and adaptations unknown to science. As our understanding of Earth’s complex geological history improves and technology advances, we may someday glimpse these missing chapters in the story of dinosaur evolution. Until then, the dinosaurs of lost continents remain a scientific mystery—a reminder that for all we’ve learned about prehistoric life, substantial portions of Earth’s biological history remain hidden beneath the oceans, their secrets perhaps permanently beyond our reach.