Imagine standing in a vast prehistoric landscape, hearing the thunderous calls of massive three-horned giants echoing across ancient plains. The Triceratops, one of the most iconic dinosaurs that ever lived, roamed North America around 68 million years ago, but what did they actually sound like? This question has puzzled scientists and dinosaur enthusiasts for decades, sparking fascinating research into the vocal capabilities of these magnificent creatures. While we can’t travel back in time to record their calls, cutting-edge science is helping us piece together the acoustic puzzle of Triceratops communication.

The Challenge of Recreating Ancient Voices

Scientists face an enormous challenge when trying to determine what extinct animals sounded like. Unlike bones and teeth, soft tissues like vocal cords rarely fossilize, leaving researchers to work like acoustic detectives. They must analyze skull structures, examine modern relatives, and use computer modeling to make educated guesses about prehistoric sounds. The Triceratops presents a particularly intriguing case because of its unique skull features and massive size. Think of it like trying to figure out what a song sounds like by only looking at the instrument – possible, but requiring incredible scientific creativity.

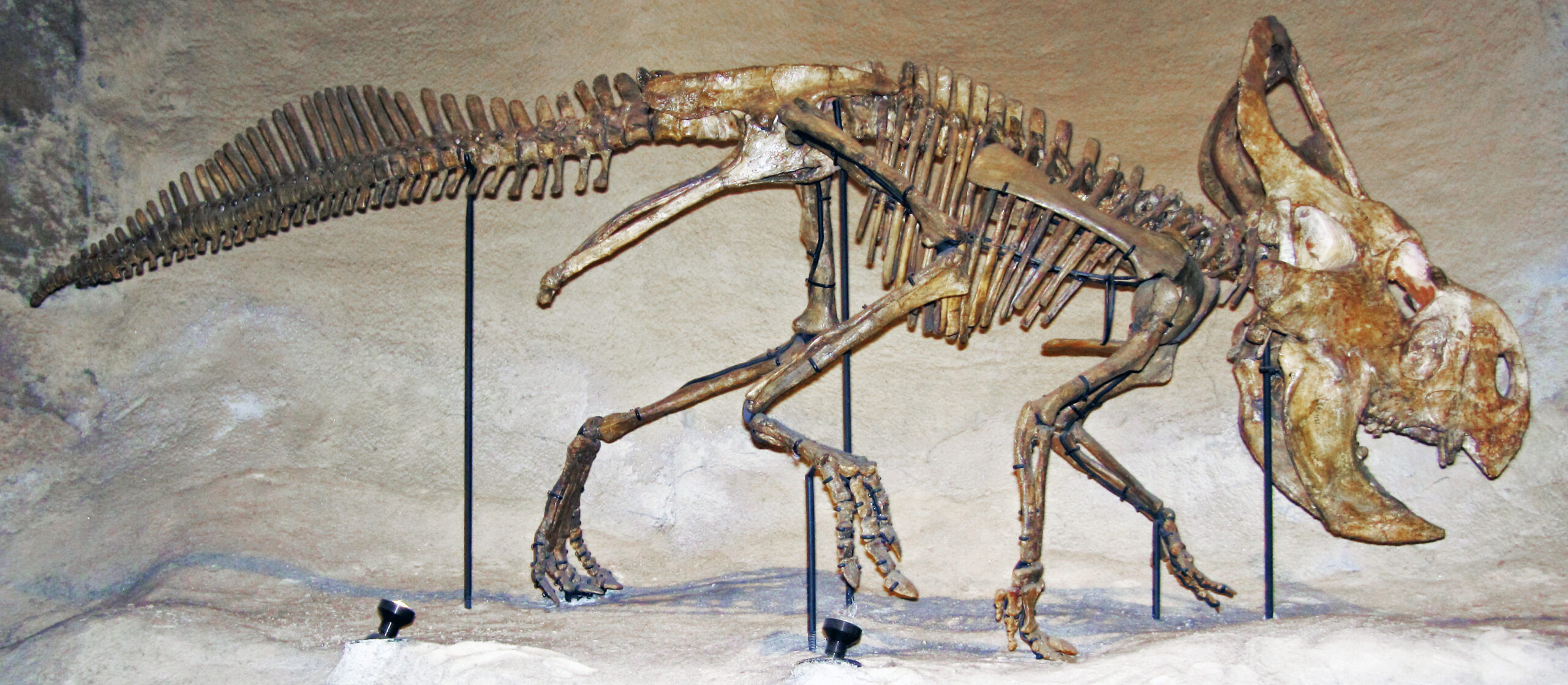

Skull Structure Clues in Triceratops

The massive skull of a Triceratops, which could measure up to 10 feet long, provides crucial hints about their vocal abilities. These skulls contained large nasal passages and sinus cavities that could have acted like resonance chambers, similar to how a guitar’s body amplifies string vibrations. The positioning of these air spaces suggests that Triceratops could produce deep, booming sounds that would travel great distances across prehistoric landscapes. Scientists have discovered that the skull’s internal structure was remarkably complex, with interconnected air pockets that would have influenced the quality and pitch of any sounds produced. This sophisticated acoustic architecture hints at a creature capable of more than just simple grunts or roars.

Modern Bird Relatives Hold Vital Clues

Birds are the closest living relatives to dinosaurs, and their vocal abilities offer fascinating insights into what Triceratops might have sounded like. Many large birds today, such as cassowaries and emus, produce deep, rumbling sounds that can travel for miles through dense forest. These booming calls serve multiple purposes, from attracting mates to warning off rivals or coordinating with family groups. The vocal organ in birds, called a syrinx, is different from mammalian vocal cords and allows for incredible sound diversity. If Triceratops possessed a similar organ, they could have produced a wide range of vocalizations, from subtle communication calls to earth-shaking territorial displays.

Size Matters in Animal Communication

The sheer size of Triceratops – weighing up to 12 tons and measuring 30 feet long – would have significantly influenced their vocal capabilities. In the animal kingdom, larger creatures typically produce lower-frequency sounds that can travel much farther than high-pitched calls. Think about how a blue whale’s song can travel hundreds of miles underwater, or how an elephant’s infrasonic rumbles can be heard by other elephants miles away. A Triceratops would likely have produced incredibly deep, powerful sounds that modern humans would feel as much as hear. These low-frequency calls would have been perfect for long-distance communication across the vast plains where these giants lived.

The Role of the Frill in Sound Production

The distinctive bony frill behind a Triceratops’s head wasn’t just for protection – it may have played a crucial role in their vocal abilities. This large, flat structure could have acted like a natural amplifier, reflecting and directing sound waves forward like a megaphone. Some scientists theorize that the frill might have vibrated when the dinosaur vocalized, adding unique harmonic qualities to their calls. The size and shape of individual frills varied between Triceratops specimens, suggesting that each individual might have had a slightly different vocal signature. This would have allowed these social creatures to recognize each other by voice alone, much like how we can identify friends by their laughter.

Crocodilian Connections to Prehistoric Sounds

Crocodilians, being archosaurs like dinosaurs, provide another window into prehistoric vocal behavior. Large crocodiles and alligators produce incredibly deep, resonant bellows that can be felt through the ground and water from great distances. These sounds are produced not just through their throat, but their entire body acts as a resonating chamber, creating vibrations that ripple through their environment. If Triceratops used similar mechanisms, their calls would have been felt as much as heard, creating a truly overwhelming sensory experience. The infrasonic components of such calls – sounds below human hearing range – could have traveled for miles, allowing these massive herbivores to stay in contact across vast territories.

Herd Communication and Social Calls

Evidence suggests that Triceratops lived in herds, which would have required sophisticated communication systems. Like modern elephants or buffalo, these prehistoric giants would have needed various types of calls for different situations – alarm calls to warn of danger, contact calls to maintain group cohesion, and probably specific sounds for coordinating movement. The complexity of managing a herd of massive animals across changing landscapes would have demanded a rich vocabulary of sounds. Picture a family of Triceratops moving across an ancient floodplain, constantly communicating through a series of deep rumbles, snorts, and perhaps even more subtle vocalizations that helped maintain their social bonds.

Mating Calls and Territorial Displays

The breeding season would have brought out the most spectacular vocal displays from Triceratops. Male dinosaurs likely competed for mates through impressive sound displays, much like how elk bugle during rutting season or how howler monkeys stake out territory. The combination of their massive size, resonant skull structure, and powerful lung capacity would have created truly awe-inspiring mating calls. These vocalizations might have been accompanied by visual displays involving their colorful frills and intimidating horns, creating a multi-sensory spectacle that would have dominated the prehistoric soundscape. The deepest, most powerful calls would have signaled the strongest, most desirable mates.

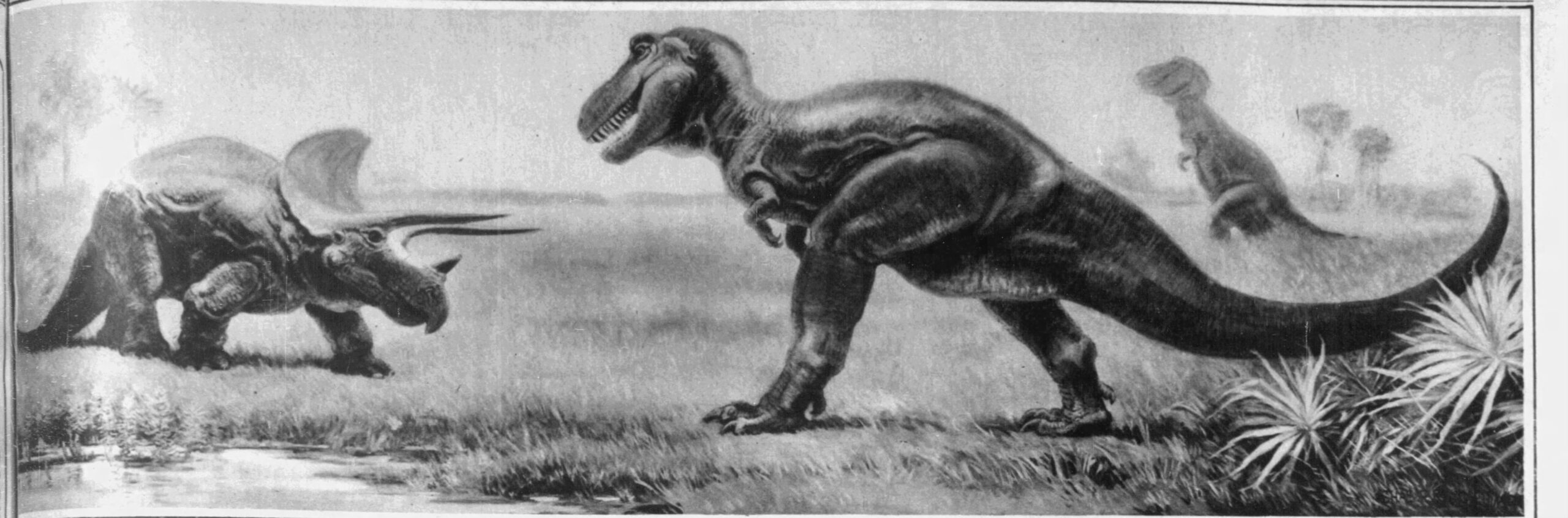

Defensive and Alarm Vocalizations

When faced with predators like Tyrannosaurus rex, Triceratops would have needed effective alarm calls to warn their herd and coordinate defensive strategies. These alarm calls were probably sharp, attention-grabbing sounds that could cut through the ambient noise of the prehistoric environment. Think of how a mother goose’s alarm call instantly alerts her goslings to danger – Triceratops likely had similar urgent warning calls. The ability to quickly communicate threat levels and coordinate group responses would have been crucial for survival in a world filled with massive predators. These defensive calls might have been some of the loudest sounds these creatures could produce, designed to startle attackers and rally the herd.

Environmental Acoustics of the Cretaceous Period

The world of the Triceratops was acoustically very different from today’s environments. The late Cretaceous period featured vast, open landscapes with different vegetation and atmospheric conditions that would have affected how sounds traveled. Without the dense forests and urban noise of modern times, the prehistoric soundscape would have been dominated by natural sounds – wind, water, and the calls of various dinosaur species. In this environment, the deep, booming calls of Triceratops would have carried incredibly far, perhaps for many miles across open plains. The acoustic properties of their world would have shaped how these creatures evolved their communication strategies.

Computer Modeling of Dinosaur Vocalizations

Modern technology is revolutionizing our understanding of how dinosaurs might have sounded. Scientists use sophisticated computer models that analyze skull structure, air flow patterns, and resonance chambers to simulate prehistoric vocalizations. These digital reconstructions suggest that Triceratops could have produced sounds ranging from deep, subsonic rumbles to higher-pitched calls for close-range communication. The models take into account the size and shape of nasal passages, the volume of air that could be moved, and the resonant properties of different skull features. While these simulations can’t perfectly recreate the actual sounds, they provide our best scientific estimates of what these magnificent creatures might have sounded like.

Comparing Triceratops to Other Horned Dinosaurs

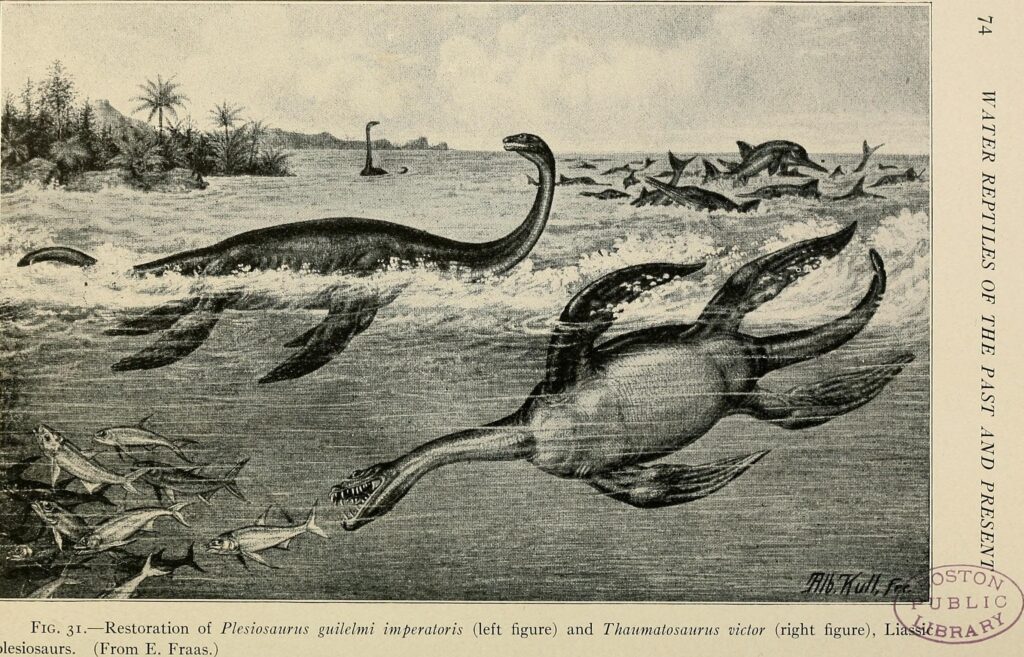

The ceratopsian family, which includes Triceratops, featured many species with different horn arrangements and frill shapes, likely resulting in unique vocal signatures for each species. Smaller ceratopsians like Protoceratops probably had higher-pitched calls, while larger relatives like Torosaurus might have produced even deeper sounds than Triceratops. The diversity in skull structures across this dinosaur family suggests a rich variety of vocalizations, each adapted to specific environmental and social needs. Some species might have been the “singers” of the dinosaur world, while others were the “drummers,” creating a complex acoustic ecosystem. This vocal diversity would have helped different species avoid confusion and maintain clear communication within their own groups.

The Mystery of Infrasonic Communication

One of the most intriguing possibilities is that Triceratops used infrasonic communication – sounds below the range of human hearing. Many large modern animals, including elephants, whales, and rhinos, use infrasound to communicate over vast distances. These low-frequency sounds can travel through dense vegetation, around obstacles, and across many miles without losing their strength. If Triceratops possessed this ability, much of their communication would have been completely silent to human ears, felt only as vibrations through the ground. This “secret” communication channel would have allowed them to coordinate herd movements, share information about food sources, and maintain social bonds across enormous territories without alerting predators to their presence.

What We Still Don’t Know

Despite all our scientific advances, many mysteries remain about Triceratops vocalizations. We can’t be certain whether they had vocal cords like mammals, a syrinx like birds, or some entirely different sound-producing mechanism. The emotional range of their calls – whether they could express joy, fear, anger, or other complex emotions through sound – remains purely speculative. We also don’t know how their vocalizations might have changed throughout their lives, from baby Triceratops with presumably higher-pitched calls to the deep, resonant voices of full-grown adults. The specific “language” they might have developed, with different calls meaning different things, is lost to time, leaving us to imagine the rich acoustic conversations that once filled prehistoric landscapes.

Conclusion

The quest to understand what Triceratops sounded like combines paleontology, acoustics, and computer science to paint a picture of prehistoric communication that’s both scientifically grounded and wonderfully mysterious. These massive creatures likely filled their ancient world with deep, powerful calls that would have been unlike anything in today’s natural world, creating an acoustic landscape as magnificent and awe-inspiring as the dinosaurs themselves. What sounds do you think would have been most important for these gentle giants to survive in their dangerous world?