You’ve heard about Tyrannosaurus rex, Triceratops, and countless other dinosaurs that captured our imagination. Yet these spectacular beasts weren’t Earth’s first rulers. Long before the first dinosaur took its initial breath, ancient nightmares stalked our planet – armored behemoths with bone-crushing jaws, massive millipede-like creatures the size of cars, and flying predators with wingspans wider than a basketball court.

These forgotten apex predators dominated Earth for millions of years, evolving into forms so alien and terrifying that they make modern predators look tame. From the crushing depths of Devonian seas to the oxygen-rich swamps of the Carboniferous, these ancient titans shaped life on Earth in ways we’re only beginning to understand. So let’s get started on this journey through deep time to meet the monsters that ruled before the Age of Reptiles.

Dunkleosteus: The Armored Terror of Ancient Seas

Picture a predator that could bite down at a force of approximately 5,300 pounds per square inch, capable of crushing steel and bone with equal ease. Dunkleosteus existed during the Late Devonian period, about 382–358 million years ago, and was one of the first vertebrate apex predators of any ecosystem. This armored nightmare didn’t just hunt – it dominated every creature unfortunate enough to share its waters.

Dunkleosteus terrelli is one of the largest known placoderms, with its maximum size being variably estimated as anywhere from 4.1–10 metres (13–33 ft) by different researchers. Honestly, imagine encountering something that massive in the water. Like all Placoderms, Dunkleosteus was toothless. However, its armored jaw plates formed massive self-sharpening blades!

What made this creature particularly terrifying was its hunting strategy. Using its powerful jaws, Dunkleosteus was able to open its mouth in just 20 milliseconds and, in doing so, create a vacuum that would have sucked in its prey. Its mouth would have then clamped shut, its blades sinking straight through the shell, bony plates, or fleshy skin of its prey. Nothing was off the menu for Dunkleosteus, even other Dunkleosteus.

Arthropleura: The Giant Millipede That Terrorized Forest Floors

At 2.6m in length and nearly 50kg in weight, Arthropleura is widely regarded as the largest terrestrial invertebrate to ever live. Think about that for a moment – a millipede longer than most cars and heavier than an adult human. Arthropleura armata was the largest land-based invertebrate to have ever lived on Earth. It was a species of giant millipede that lived near modern-day Scotland and North America around 320 million years ago.

Despite its intimidating size, this ancient giant wasn’t the monster you might expect. Like today’s millipedes, Arthropleura was a detritivore that fed on either dead and decaying plant matter or animal remains – on the rare occasions that it stumbled across them. However, its sheer size made it virtually untouchable in its ecosystem.

In terms of natural predators, Arthropleura had very few if any that it had to watch out for. As mentioned above, it was the largest animal in its environment by far and its size alone would have likely deterred any would-be predators. It was also covered in thick dorsal armor made of chitin, which gave it an extra layer of protection. Arthropleura was a survivor, persisting for more than 50 million years and weathering a series of climatic events in the Late Carboniferous before it ultimately faced extinction in the Early Permian, ~290 million years ago.

Meganeura: The Giant Dragonfly That Owned the Skies

With single wing length reaching 32 centimetres (13 in) and a wingspan about 65–75 cm (2.13–2.46 ft), M. monyi is one of the largest-known flying insect species. With wings spanning up to 28 inches (about 2.3 feet) – this prehistoric dragonfly was roughly the size of a modern hawk. Imagine encountering one of these aerial predators during a peaceful walk through the forest!

Meganeura wasn’t just big for show; it was a perfectly designed killing machine. Its massive compound eyes, each containing thousands of individual lenses, gave it incredible vision for spotting prey from great distances. Those powerful wings could propel it at speeds that would make modern dragonflies jealous, while its strong mandibles could crush smaller insects with ease.

Meganeura had spines on the tibia and tarsi sections of the legs, which would have functioned as a “flying trap” to capture prey. These giants ruled the airways for millions of years, patrolling their territories like feathered raptors do today. They likely preyed on smaller flying insects, amphibians, and probably even small early reptiles, making them apex predators of their time.

Inostrancevia: The Saber-Toothed Nightmare of the Permian

Perhaps the most charismatic of all Permian fauna are the gorgonopsians, with their lion heads and saber teeth. While still basal and cold-blooded, they were the top predators of the Late Permian, the largest of which, Inostrancevia, may have weighed half a tonne, or the size of a very large tiger. This creature represented the pinnacle of pre-dinosaur predatory evolution, combining massive size with weaponry that would make modern big cats envious.

The Permian did have its predators, and one of the most impressive was Inostrancevia – one of the largest and most fearsome of a group known as the Gorgonopsids. These creatures weren’t true mammals or reptiles but represented something in between, occupying a crucial evolutionary position.

Late Permian faunas are dominated by advanced therapsids such as the predatory sabertoothed gorgonopsians and herbivorous beaked dicynodonts, alongside large herbivorous pareiasaur parareptiles. Though these animals lived before dinosaurs evolved, they filled similar ecological niches with remarkable efficiency. While it’s unknown whether their saber teeth would have been visible outside the mouth in life, it’s not impossible that they would have been, especially because ancestral amniotes didn’t have the flexible, loose facial skin that allow modern mammals to chew with their mouths closed and make complex facial expressions. Certain modern animals with large, non-tusk canines, like muntjac deer, red foxes, and Tasmanian devils, have their teeth protruding from their mouths most or all of the time, without ill effects on the enamel. So I chose to depict my gorgonopsians that way, mostly because it’s more fun.

Cotylorhynchus: The Massive Plant-Eater with Seven Chins

Cotylorhynchus was massive, estimated to have topped 4.5 meters (14.8 feet) in length and weighing around 330 kilograms (728 pounds). This ancient giant looked like nature’s first attempt at creating a massive land herbivore, though the result was utterly bizarre by today’s standards.

We simply can’t touch on synapsids without a hat tip to Cotylorhynchus, an animal that’s best described as a pea-headed croc with about seven more chins than you’d expect. It had a barrel-shaped body and broad, thick skull, and was an important part of the ecosystem as one of the earliest large herbivores.

This creature represents an important evolutionary milestone – The Permian period lasted from 299 to 251 million years ago and produced the first large plant-eating and meat-eating animals. Cotylorhynchus proved that massive size was possible on land long before dinosaurs appeared, though its unusual proportions suggest early land animals were still experimenting with different body plans.

Pulmonoscorpius: The Cat-Sized Scorpion

The gigantic Pulmonoscorpius from the early Carboniferous reached a length of up to 70 cm (2 ft 4 in). There was also a giant scorpion, known as Pulmonoscorpius, that exceeded lengths of 70cm and was one of the top predators in Scotland during the Early Carboniferous. Imagine walking through ancient forests and encountering a scorpion nearly the size of a house cat stalking through the undergrowth.

Pulmonoscorpius kirktonensis was a large scorpion-like species that lived between 336 and 326 million years ago. Its fossil remains were first discovered at the East Kirkton Quarry in Scotland (1994). This discovery revealed that even arachnids reached gigantic proportions during the oxygen-rich Carboniferous period.

Pulmonoscorpius: This early scorpion likely grew to be over 2 feet long and used its size to overpower prey in the open. Unlike modern scorpions that rely primarily on stealth and ambush tactics, Pulmonoscorpius could use its massive size to actively hunt and overpower prey that would be impossible for modern scorpions to tackle.

Temnospondyls: The Crocodile-like Amphibian Giants

Triassic amphibians were dominated by temnospondyls. Temnospondyls could reach sizes not seen in modern amphibians, such as the 10-foot-long metoposaurs of Petrified Forest National Park. These semiaquatic predators looked something like salamanders with enormous broad, flat, toothy heads. These weren’t your garden-variety amphibians – they were apex predators in their own right.

Amphibians were primarily represented by the temnospondyls, giant aquatic predators that had survived the end-Permian extinction and saw a new burst of diversification in the Triassic, before going extinct by the end; however, early crown-group lissamphibians (including stem-group frogs, salamanders and caecilians) also became more common during the Triassic and survived the extinction event.

These creatures bridged the gap between aquatic and terrestrial life in ways that modern amphibians simply cannot match. They represented the last gasp of giant amphibians before reptiles and early mammals took over terrestrial ecosystems. Their massive heads and powerful jaws made them formidable predators in the semi-aquatic environments they inhabited.

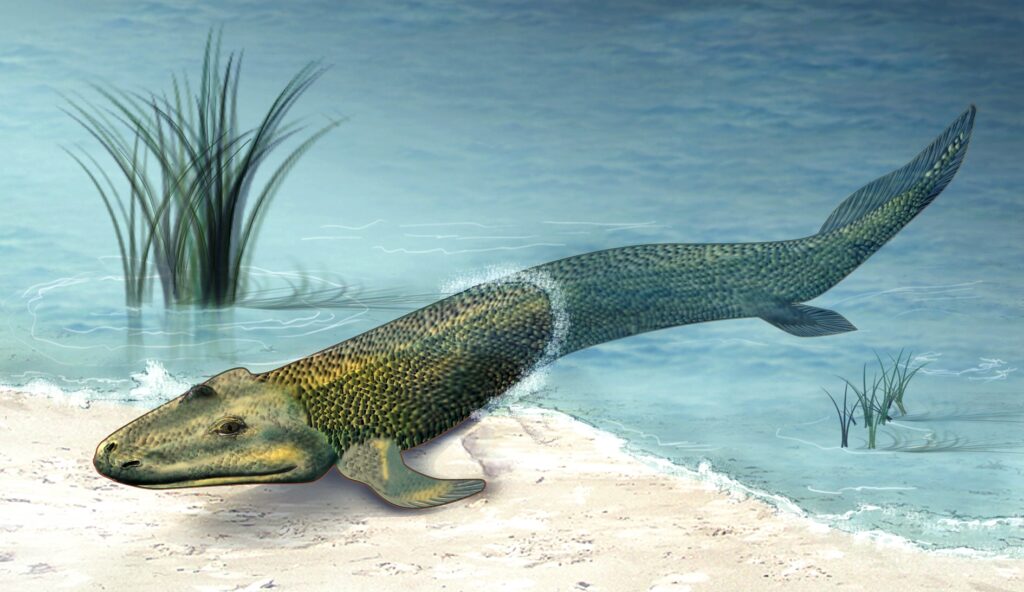

Tiktaalik: The Fish That Learned to Walk

Fish aren’t typically known for their ability to walk on land, but Tiktaalik wasn’t your typical fish. It was, by definition, a fish, but sporting primitive, air-breathing lungs (as well as gills) and four fleshy appendages that resembled limbs, it was well on its way to becoming a fully fledged, terrestrial tetrapod. This was evolution in action – a creature caught in the very act of making one of life’s most significant transitions.

From fossils found in Arctic Canada, it’s estimated that Tiktaalik grew to lengths of 3m. This huge size, combined with large jaws full of needle-like teeth, a mobile neck and eyes on the top of its head, suggests it was a predator specially adapted for hunting fish in the shallows.

As mentioned above, Tiktaalik was a trailblazer that paved the way for all vertebrates that live on land today, including us. However, it was also a predator that, 375 million years ago, terrorised a lot of the animals that lived in and around the shallow, freshwater swamps that once covered parts of northern Canada. Tiktaalik is often referred to as a ‘fishapod’ – an animal that blurs the lines between ‘fish’ and ‘tetrapod’. In life, it would have looked quite similar to today’s crocodiles, with a flat, pointed snout, upward-pointing eyes, paddle-shaped limbs, and an elongated, streamlined body.

The Giant Insects of the Carboniferous Oxygen World

The Carboniferous was dominated by huge expanses of swampland, and all of the vegetation released so much oxygen that atmospheric oxygen levels were about 67% higher than they are today (reaching 35% compared to today’s 21%). Arthropods responded to this huge increase in oxygen by getting huge themselves. This created a world where insects ruled both land and air with unprecedented size and ferocity.

Other than the dragonfly-like Meganeura, this prehistoric world played host to several other intimidating insects: Arthropleura: These millipede-like organisms were the largest known land invertebrates of all time, with lengths that reached up to 8.5 feet. Pulmonoscorpius: This early scorpion likely grew to be over 2 feet long and used its size to overpower prey in the open. Proliferation was not limited to just the traditional predators – even everyday insects like cockroaches and mayflies saw massive growth.

Even mayflies, those delicate insects known for their brief adult lives, got supersized during the Carboniferous. Some species had wingspans reaching up to 18 inches, making them among the largest mayflies ever discovered. These gentle giants would have created spectacular mating swarms above ancient rivers and lakes. So arthropods got big because they had to survive, not because they could, and luckily for all of us, most of the giant insects died out at the end of the Carboniferous when the Earth began to get drier and the swamps they made their homes in disappeared.

The Great Permian Extinction: When the Monsters Died

The Permian ended with the largest mass extinction in the history of Earth: some 90% of all plant and animal life was wiped out. The Permian (along with the Paleozoic) ended with the Permian–Triassic extinction event (colloquially known as the Great Dying), the largest mass extinction in Earth’s history (which is the last of the three or four crises that occurred in the Permian), in which nearly 81% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial species died out, associated with the eruption of the Siberian Traps.

This catastrophic event marked the end of an era dominated by these alien predators. The Permian-Triassic extinction event, also known as the Great Dying, took place roughly 252 million years ago and was one of the most significant events in the history of our planet. By some estimates, it may have taken up to 10 million years for the planet to recover from the devastation caused by the Great Dying.

It took well into the Triassic for life to recover from this catastrophe; on land, ecosystems took 30 million years to recover. The extinction cleared the stage for new players – eventually including the dinosaurs that would dominate the planet for the next 165 million years. Yet it also meant the end of some of Earth’s most remarkable and terrifying predators.

Conclusion

These forgotten apex predators remind us that Earth’s history is far stranger and more violent than we often imagine. From bone-crushing armored fish to flying insects with hawklike wingspans, from saber-toothed mammal ancestors to millipedes the size of cars, life experimented with forms that seem almost alien today. They ruled their respective worlds with the same dominance that later dinosaurs would achieve, yet they remain largely unknown to the general public.

These ancient monsters shaped evolution in profound ways, driving prey species to develop armor, speed, and cunning that would influence life’s trajectory for millions of years. Their legacy lives on in the descendants that survived the great extinctions – including, ultimately, us. Understanding these forgotten rulers gives us perspective on how dynamic and resilient life can be, even in the face of unimaginable catastrophe.

What would you have guessed was Earth’s largest land predator 300 million years ago? Tell us in the comments.