Throughout history, human and animal remains have served as invaluable scientific resources, offering insights into evolution, disease, culture, and anatomy. However, the path from discovery to scientific study has often been intercepted by theft, commercial sale, or unethical acquisition. This dark chapter in scientific history reveals complex intersections between science, ethics, colonialism, and cultural respect. The unauthorized taking of skeletal remains has not only impeded scientific progress but also perpetuated historical injustices and violated cultural sensitivities. From grave robbing in the Victorian era to modern black market fossil trading, these practices continue to cast shadows over paleontology, archaeology, and anthropology.

The Body Snatchers of 19th Century Medicine

In the 19th century, medical schools faced a critical shortage of cadavers needed for anatomical education. This shortage gave rise to the macabre profession of “resurrection men” or “body snatchers” who exhumed fresh corpses to sell to medical institutions. In Edinburgh, the infamous duo William Burke and William Hare took this practice to horrifying extremes, murdering sixteen people to sell their bodies to Dr. Robert Knox for dissection. This scandal eventually led to the Anatomy Act of 1832 in Britain, which increased the legal supply of cadavers by allowing unclaimed bodies from workhouses and hospitals to be used for medical study. Before this legislation, countless bodies were stolen before proper scientific examination or documentation could occur, creating gaps in medical knowledge and anatomical records that persist to this day.

The Piltdown Man Fraud

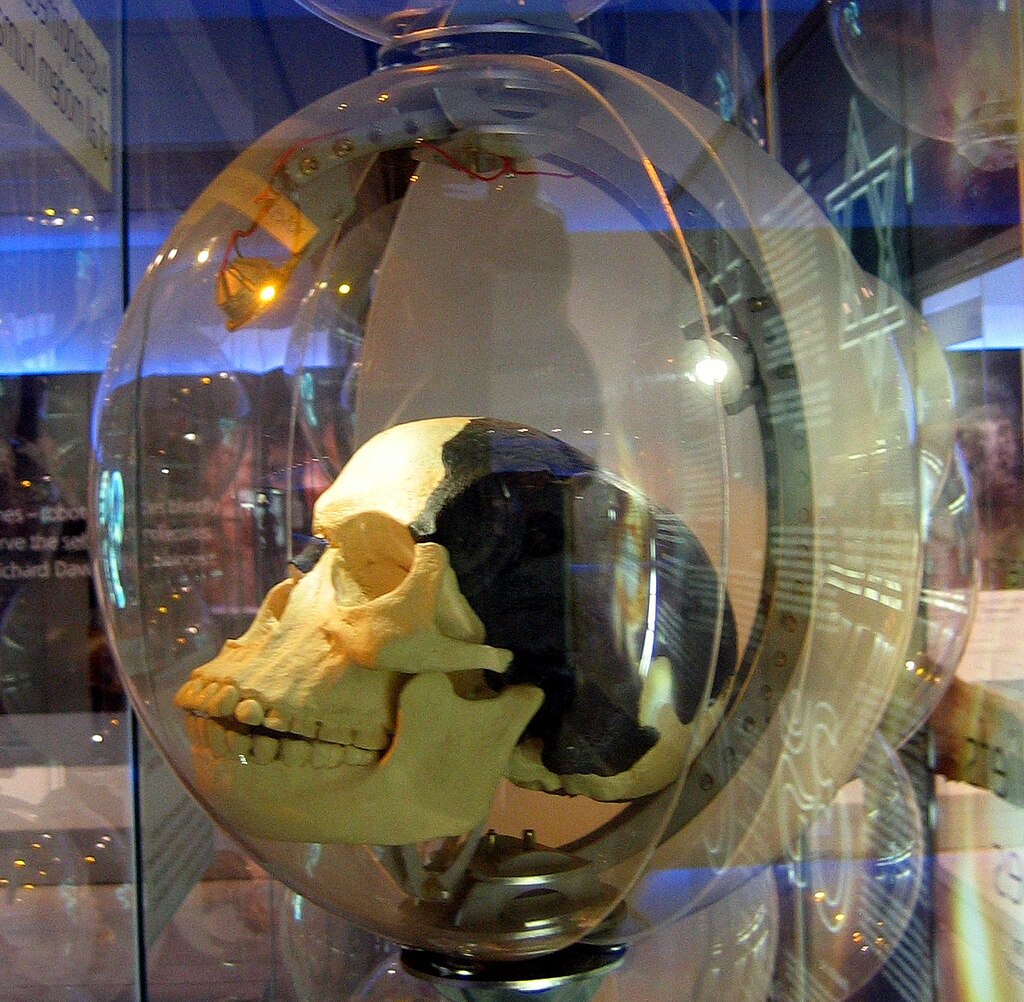

One of the most notorious scientific frauds involving skeletal remains was the Piltdown Man hoax, discovered in 1912 in England. Amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson presented what he claimed were fragments of a previously unknown early human ancestor, combining a human-like skull with an orangutan jawbone. For forty years, these falsified remains diverted legitimate scientific inquiry and delayed accurate understanding of human evolution. What made this case particularly damaging was that genuine fossil specimens that could have advanced evolutionary science were overlooked or misinterpreted as scientists attempted to fit new discoveries into the fraudulent Piltdown paradigm. The bones that should have been available for proper scientific study were instead manipulated, artificially aged, and falsely presented, effectively “stealing” them from legitimate scientific inquiry for decades.

Colonial Acquisition of Indigenous Remains

During the era of European colonization, the remains of indigenous peoples were systematically collected, often without consent, and shipped to museums and institutions in Europe and North America. The Smithsonian Institution alone once housed thousands of Native American remains, many acquired through problematic means. Skull collecting became particularly prevalent in the 19th century, fueled by pseudoscientific theories like phrenology that claimed to determine intelligence and character from skull shapes. These practices not only violated indigenous burial traditions but also prevented communities from conducting their own cultural studies and interpretations of ancestral remains. The scientific narratives developed from these unethically obtained specimens often reinforced racist ideologies rather than producing objective knowledge, demonstrating how the theft of remains corrupted both the scientific process and its outcomes.

The Black Market for Dinosaur Fossils

The commercial market for dinosaur fossils has exploded in recent decades, with specimens fetching millions of dollars at auction. The infamous “Sue” T. rex skeleton sold for $8.4 million in 1997, setting off a fossil gold rush that continues today. When commercially valuable specimens are quickly excavated and sold to private collectors, scientists lose critical contextual information about the discovery site, associated remains, and geological data. Mongolia and China have been particularly affected by illegal fossil poaching, with specimens smuggled across borders before local scientists can properly document or study them. The rush to extract fossils for profit often results in damaged specimens, as proper paleontological techniques are abandoned in favor of speed, permanently destroying scientific data that cannot be recovered once the contextual integrity of a site is compromised.

The Tragedy of Ötzi the Iceman

When hikers discovered the mummified remains of a 5,300-year-old man in the Alps in 1991, initial mishandling nearly destroyed one of the most important archaeological finds of the century. Before proper scientific protocols could be implemented, multiple individuals handled the body, removing it from the ice without documenting its exact position or collecting associated artifacts. The primitive extraction damaged Ötzi’s hip and tore his left arm. Furthermore, the body was stored improperly before reaching the proper authorities, allowing thawing and bacterial growth that potentially destroyed valuable genetic material. The mishandling of this discovery demonstrates how even well-intentioned but unauthorized interaction with ancient remains can permanently compromise scientific value before experts can implement proper preservation and study methods.

Stolen Egyptian Antiquities and Mummies

Ancient Egypt’s rich burial traditions have made its tombs targets for looters for millennia, but the 19th century saw systematic plundering reach new heights. European collectors and museums acquired countless mummified remains through questionable means, often destroying archaeological contexts in the process. Mummy unwrapping parties became fashionable social events in Victorian England, where ancient human remains were desecrated for entertainment before any scientific study could occur. The commercial trade in Egyptian mummies was so extensive that they were even ground up for paint pigments and medicine. Recent scholarship has revealed that many museum collections contain Egyptian remains acquired through colonial exploitation, with documentation deliberately obscured to hide unethical acquisition methods, thus preventing both scientific analysis and potential repatriation.

The Case of Sarah Baartman

The tragic story of Sarah Baartman, a Khoikhoi woman from South Africa who was exhibited as a curiosity in 19th century Europe, represents one of the most dehumanizing examples of scientific exploitation. After her death in 1815, Georges Cuvier, a prominent French naturalist, dissected her body and preserved her brain and genitals for display at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. These remains were exhibited until 1974, decades after such displays had been widely condemned as racist. South Africa repeatedly requested the return of her remains, but France refused until 2002, nearly two centuries after her death. During this time, her remains were subjected to various “studies” that reinforced racist pseudoscience rather than legitimate anthropology, demonstrating how stolen human remains often served to validate prejudice rather than advance genuine scientific understanding.

The Kennewick Man Controversy

The discovery of a 9,000-year-old skeleton along the Columbia River in Washington State in 1996 sparked a nine-year legal battle between scientists and Native American tribes. While anthropologists viewed the remains as a rare opportunity to study ancient North American populations, local tribes considered the remains ancestral and sought their return under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. During the lengthy court proceedings, scientific study was delayed and limited, with deterioration occurring due to improper storage conditions. When DNA analysis was finally conducted in 2015, it confirmed the skeleton’s genetic connection to Native Americans, supporting the tribes’ claims. This case highlighted the tensions between scientific inquiry and indigenous rights, and how legal disputes over possession can prevent timely research while remains deteriorate.

The Gigantopithecus Black Market

Gigantopithecus blacki, the largest known primate to have ever lived, is primarily known from fossil teeth and jaw fragments found in Chinese apothecary shops, where they were sold as “dragon teeth” for traditional medicine. Most scientific knowledge about this extinct ape comes from specimens that were commercially collected without proper documentation of their discovery locations or geological context. The commercial trade in these fossils has been ongoing since the 1930s, with many specimens disappearing into private collections before scientists could study them. Without knowing the precise caves and strata where these remains originated, paleontologists lose critical information about the animal’s habitat, diet, and evolutionary timeline. This case demonstrates how commercial markets can simultaneously reveal the existence of important species while severely limiting scientific understanding of them.

The Trafficking of Human Skulls on Social Media

A disturbing modern trend involves the buying and selling of human skulls through social media platforms and online marketplaces. Research published in 2020 identified hundreds of human skulls for sale on Instagram, Facebook, and eBay, many with dubious provenance and potentially representing recently deceased individuals from vulnerable populations. While sellers often claim these are “medical specimens,” many lack proper documentation and may have been looted from cemeteries or archaeological sites. This unregulated trade prevents proper scientific study of these remains, which might otherwise contribute to bioarchaeological research, forensic science, or medical education. Additionally, the online market creates financial incentives for grave robbing in economically disadvantaged regions, particularly in Southeast Asia and Africa, where protection of burial sites may be limited by resource constraints.

The Tragic Loss of Homo floresiensis Specimens

The 2003 discovery of Homo floresiensis (nicknamed “the hobbit”) on the Indonesian island of Flores represented a groundbreaking addition to our understanding of human evolution. However, the scientific study of these remains was severely compromised when Indonesia’s most prominent paleoanthropologist, Teuku Jacob, removed the specimens from their secure repository without proper authorization. During the several months the bones were in his possession, they were badly damaged—the pelvis was broken, a facial bone was cracked, and portions were detached from the mandible. Additionally, Jacob made unauthorized casts that further damaged the fragile specimens. When the remains were finally returned, scientists discovered that long-term scientific value had been compromised through this unauthorized “borrowing,” demonstrating how even within the scientific community, improper handling and institutional rivalries can effectively “steal” specimens from comprehensive study.

The Lost Legacy of Franz Boas’ Brain Collection

Anthropologist Franz Boas, often considered the father of American anthropology, assembled a collection of hundreds of human brains in the early 20th century to disprove racist theories about brain size and intelligence. Ironically, many of these brains were obtained through problematic means from indigenous communities without proper consent. After Boas’ death, portions of this collection were misplaced, damaged, or discarded during institutional moves and reorganizations. In a twist of scientific negligence, the very brains collected to counter scientific racism were themselves treated carelessly, with many lost before modern neuroimaging techniques could properly analyze them. This case illustrates how even collections assembled for legitimate scientific purposes can be effectively “stolen” from future research through institutional neglect, changing research priorities, and inadequate curation practices.

Ethical Frameworks for the Future

The scientific community has increasingly developed ethical frameworks to address the historical injustices surrounding stolen or improperly acquired remains. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act in the United States, passed in 1990, requires federally funded institutions to return Native American cultural items and human remains to their descendants. Similar legislation has been enacted in Australia regarding Aboriginal remains and in New Zealand for Māori ancestral remains. Modern paleontological and archaeological codes of ethics now emphasize proper documentation, local community involvement, and legal acquisition of specimens. Digital technologies increasingly allow for detailed 3D scanning of remains before repatriation, creating a compromise that respects cultural sensitivities while preserving scientific data. These evolving practices acknowledge that ethical considerations and scientific progress need not be in opposition, but can instead reinforce each other through respectful collaboration.

Conclusion

The history of stolen, sold, or misappropriated skeletal remains represents a complex legacy that modern science continues to grapple with. These cases highlight not only the scientific knowledge lost when specimens are removed from proper study contexts but also the ethical violations inherent in treating human and animal remains as commodities. Today’s researchers face the dual challenge of advancing scientific understanding while addressing historical injustices and respecting cultural sensitivities. Moving forward, transparent acquisition practices, collaborative relationships with source communities, and recognition of both scientific and cultural values will be essential to ensure that the bones that help us understand our past can be studied with integrity and respect.