Long before we understood dinosaurs as the diverse group of animals that dominated Earth for over 165 million years, these prehistoric creatures were grossly misinterpreted. For much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the scientific community viewed dinosaurs simply as enormous reptiles that dragged their massive bodies across primordial landscapes. This mistaken view shaped everything from scientific research to popular culture, creating images of dinosaurs as sluggish, cold-blooded behemoths that bore little resemblance to what we know today. The journey from this misconception to our current understanding represents one of the most dramatic shifts in scientific thought, revealing how scientific knowledge evolves as new evidence emerges and paradigms shift.

The First Dinosaur Discoveries

The modern story of dinosaurs began in the early 19th century with several key discoveries in England. In 1822, Mary Ann Mantell and her husband, Gideon, discovered large fossil teeth that would later be identified as belonging to Iguanodon. Before this, various fossils had been found throughout history, but they were typically attributed to biblical giants or mythological creatures. The Mantells compared their fossil teeth to those of modern iguanas, noting similarities but at a much larger scale. This led to the interpretation that these remains belonged to enormous ancient lizards. The name “dinosaur” hadn’t even been coined yet, and these mysterious creatures were simply considered extinct reptiles of extraordinary size that had somehow vanished from Earth.

Sir Richard Owen and the Term “Dinosauria”

In 1842, British anatomist Sir Richard Owen examined fossils of Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus and recognized that these creatures shared certain anatomical features that distinguished them from modern reptiles. He coined the term “Dinosauria,” meaning “terrible lizard,” to classify this group of extinct animals. Despite recognizing their uniqueness, Owen still envisioned dinosaurs as essentially giant lizards that somewhat resembled modern reptiles like crocodiles and monitor lizards, just dramatically scaled up. His conception, while an advancement at the time, still assumed dinosaurs were cold-blooded and probably moved with splayed limbs like modern reptiles. Owen’s influence was immense, and his vision of dinosaurs would dominate scientific thought for decades to come.

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

Perhaps nothing cemented the “giant lizard” image of dinosaurs in the public imagination more than the Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures, created in the 1850s under Owen’s scientific direction. These life-sized models, still standing today in London, were the world’s first dinosaur reconstructions and represented what was considered cutting-edge science at the time. The sculptures depicted creatures like Iguanodon as heavy, quadrupedal beasts with lizard-like features and, famously, a horn on their nose (which scientists later discovered was a thumb spike). These models had massive, lizard-like bodies with legs sprawling outward rather than positioned beneath them, reinforcing the giant reptile misconception. For generations of visitors, these sculptures defined what dinosaurs looked like, despite being wildly inaccurate by modern standards.

The Bone Wars Era

In the late 19th century, the infamous “Bone Wars” between paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh led to the discovery of numerous dinosaur species in the American West. Despite their bitter rivalry and sometimes questionable practices, their work greatly expanded the catalog of known dinosaur species and provided more complete skeletons than had previously been available. However, even with these discoveries, the dominant interpretation remained that dinosaurs were essentially overgrown lizards. Marsh’s reconstruction of Brontosaurus (now Apatosaurus) depicted it as a massive, swamp-dwelling beast that needed water to support its enormous weight. Although these paleontologists made remarkable discoveries, their interpretations remained constrained by the reptilian paradigm, with dinosaurs envisioned as slow, cold-blooded creatures that could hardly support their weight on land.

The Influence of Victorians on Dinosaur Perception

Victorian-era scientists brought their own cultural biases to dinosaur interpretation, seeing nature as hierarchical with mammals at the pinnacle of evolution. This worldview influenced how they understood dinosaurs, viewing them as evolutionary failures rather than the successful animals we now know them to be. The Victorian fascination with progress and the idea that nature was constantly improving meant dinosaurs were often characterized as primitive, inefficient creatures that nature had rightfully discarded. This perspective reinforced the image of dinosaurs as sluggish, dim-witted animals, an unflattering contrast to the supposedly superior mammals that would eventually replace them. The notion of dinosaurs as evolutionary failures helped explain their extinction in a way that fit with Victorian sensibilities about natural progression and improvement over time.

Early Museum Displays: Reinforcing Misconceptions

Early museum displays of dinosaur fossils further reinforced the giant lizard paradigm through their mounting techniques and accompanying descriptions. Fossils were frequently assembled in positions that mimicked modern reptiles, with tails dragging on the ground and limbs sprawled outward rather than positioned directly under the body. These postures made dinosaurs appear awkward and slow, incapable of the dynamic movements we now associate with them. Museum placards and educational materials described dinosaurs in explicitly reptilian terms, emphasizing their supposedly cold-blooded nature and limited intelligence. For generations of museum-goers, these displays represented authoritative science, embedding the giant lizard image deeply in popular consciousness and making it difficult to dislodge even as evidence mounted against it.

Dinosaurs in Early Popular Culture

Early 20th-century popular culture enthusiastically embraced the giant lizard conception of dinosaurs, further cementing these misconceptions in the public imagination. Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 novel “The Lost World” depicted dinosaurs as essentially scaled-up modern reptiles still surviving on a remote plateau. Early films like the 1925 silent movie adaptation of “The Lost World” and the original 1933 “King Kong” portrayed dinosaurs as slow-moving, reptilian monsters that behaved like enormous lizards. These cultural depictions were not just entertainment—they reflected and reinforced the scientific understanding of the time. The iconic stop-motion dinosaurs created by Willis O’Brien for these films were based on the best scientific knowledge available, demonstrating how thoroughly the giant lizard paradigm dominated both scientific and popular thinking about dinosaurs for generations.

The Dinosaur Renaissance Begins

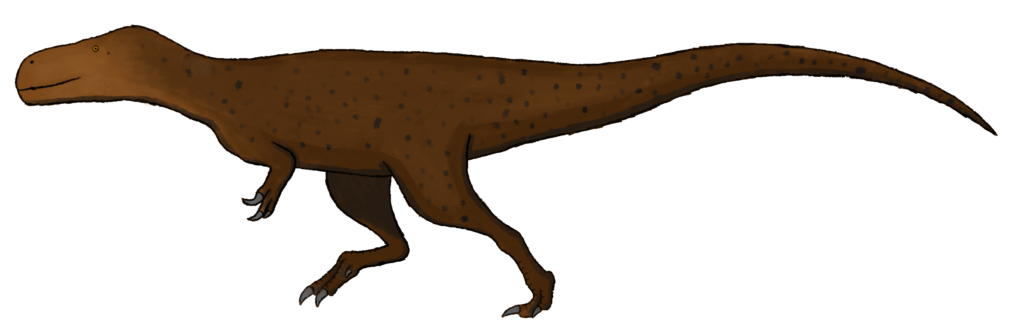

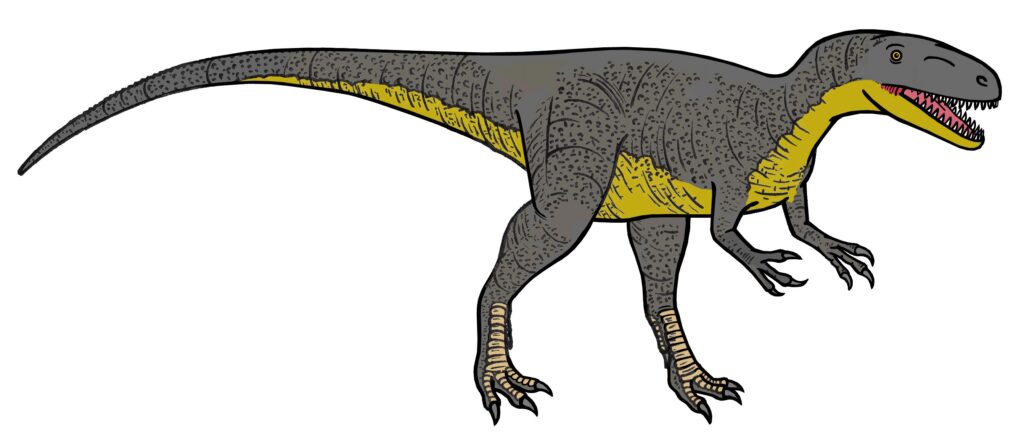

The first significant challenge to the giant lizard paradigm came in the 1960s with the work of paleontologist John Ostrom. His discovery and analysis of Deinonychus, a small predatory dinosaur, revealed anatomical features suggesting active, agile movement utterly unlike a lumbering lizard. Ostrom noted similarities between Deinonychus and birds, reviving the long-dormant hypothesis that birds evolved from dinosaurs. This work coincided with a broader reassessment of dinosaur physiology, with scientists beginning to question whether dinosaurs were truly cold-blooded like modern reptiles. The evidence suggested that at least some dinosaurs had adaptations indicating warm-bloodedness and active lifestyles, directly contradicting the slow, sluggish image that had prevailed for over a century. This period, now known as the “Dinosaur Renaissance,” marked the beginning of a fundamental shift in scientific understanding.

Robert Bakker and the Warm-Blooded Revolution

Paleontologist Robert Bakker, a student of John Ostrom, became the most vocal advocate for a revolutionary new view of dinosaurs in the 1970s and 1980s. In his influential book “The Dinosaur Heresies” (1986), Bakker presented extensive evidence that dinosaurs were warm-blooded, active animals fundamentally different from modern reptiles. He pointed to features like upright posture, predator-prey ratios in fossil ecosystems, growth rates in dinosaur bones, and the global distribution of dinosaurs in various climates as evidence that they could not have been cold-blooded like lizards. Bakker’s illustrations depicted dinosaurs as dynamic, muscular animals that held their bodies off the ground and moved with speed and agility. Although some of his specific claims remained controversial, Bakker’s work was crucial in shifting both scientific and public perception away from the giant lizard paradigm toward a more accurate understanding of dinosaurs as unique animals.

The Discovery of Feathered Dinosaurs

The final nail in the coffin for the “dinosaurs as giant lizards” theory came with the remarkable fossil discoveries from China in the 1990s and 2000s. These exquisitely preserved specimens, mainly from the Yixian Formation in Liaoning Province, revealed something extraordinary: many dinosaurs had feathers. The discovery of dinosaurs like Sinosauropteryx, Caudipteryx, and many others showed unmistakable evidence of feather-like structures on dinosaur bodies, definitively linking them to birds rather than lizards. These fossils demonstrated that the distinction between dinosaurs and birds was much blurrier than previously thought, with many features once considered uniquely avian evolving first in dinosaurs. The presence of feathers also strongly suggested warm-bloodedness in these animals, as such insulating structures would be most useful to creatures that generate their body heat, unlike modern reptiles, which rely on external heat sources.

Modern Understanding of Dinosaur Posture and Movement

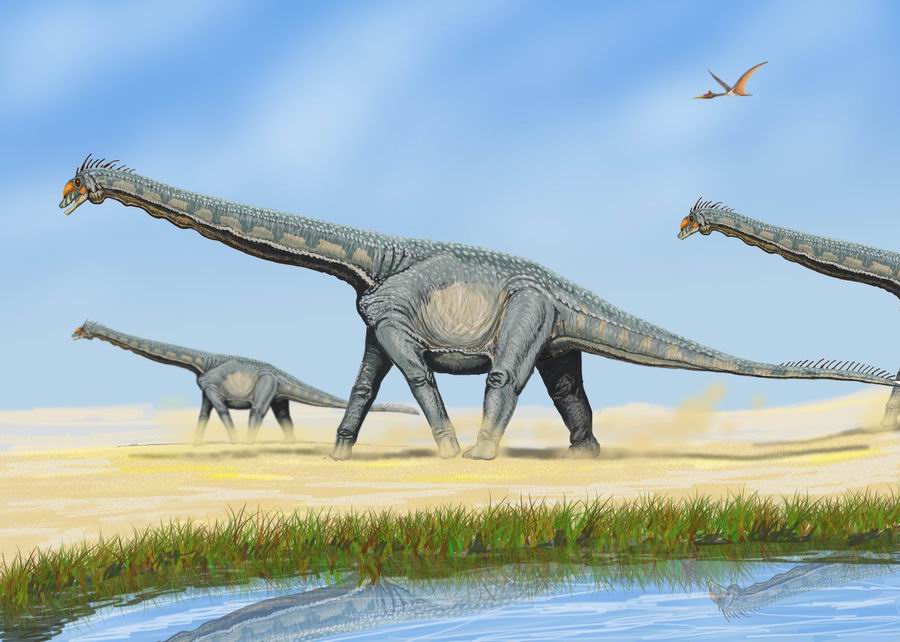

Today’s understanding of dinosaur posture and movement bears little resemblance to the lizard-like dragging envisioned by Victorian scientists. Modern research, incorporating biomechanics, computer modeling, and comparative anatomy, has revealed that dinosaurs held their bodies in ways fundamentally different from lizards. Theropod dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus stood with their spines nearly horizontal and their legs directly beneath them, while sauropods like Apatosaurus had columnar limbs positioned vertically under their bodies to support their massive weight, similar to elephants rather than crocodiles. Analysis of muscle attachment sites on fossil bones and computer simulations of movement have shown that many dinosaurs were capable of surprising speed and agility. The tail-dragging posture once depicted in museums has been replaced with the understanding that dinosaurs typically held their tails off the ground as counterbalances, further distinguishing them from the lizard model.

The Legacy of the Giant Lizard Misconception

The persistence of the giant lizard paradigm for so long despite mounting evidence against it offers important lessons about how science works and how scientific ideas change over time. This misconception persisted in part because of institutional inertia in museums and universities, the power of established scientific authorities, and the difficulty of dislodging ideas that have become embedded in both scientific literature and popular culture. Even today, outdated depictions of dinosaurs continue to appear in children’s books, toys, and some media, showing how scientific misconceptions can linger long after they’ve been debunked by new research. The shift in our understanding of dinosaurs represents one of the most dramatic paradigm shifts in modern paleontology, transforming these animals from oversized lizards to a diverse group of highly successful, often bird-like creatures that dominated Earth’s ecosystems for over 150 million years before birds—the only surviving dinosaur lineage—carried their legacy into the present.

Dinosaurs in Contemporary Science and Culture

The modern scientific understanding of dinosaurs has gradually filtered into popular culture, with films like Jurassic Park (1993) representing a watershed moment in updating public perceptions. While still containing scientific inaccuracies, this film and its sequels depicted dinosaurs as active, intelligent animals rather than slow-moving lizards. Contemporary museums have completely reimagined their dinosaur exhibits, with modern skeletal mounts showing dynamic postures and accompanying information explaining the bird-dinosaur connection. Scientific documentaries like the BBC’s “Walking with Dinosaurs” have attempted to portray dinosaurs according to the latest research, showing feathered raptors and active, complex behaviors. Despite these advances, the transition in public understanding remains incomplete, with the giant lizard image occasionally resurfacing in media and toys. The ongoing evolution of our understanding of dinosaurs highlights how scientific knowledge is always provisional, subject to revision as new evidence emerges and better methods of analysis are developed.

How Science Reimagined Dinosaurs Beyond the Giant Lizard Myth

The journey from viewing dinosaurs as oversized, lumbering lizards to understanding them as diverse, often feathered animals more closely related to birds than to modern reptiles represents one of science’s most remarkable transformations. This shift wasn’t merely a minor adjustment to scientific thinking but a complete overhaul of how we conceptualize a major group of animals that dominated Earth for far longer than humans have existed. Today’s vision of dinosaurs—active, diverse, often feathered, and in many cases remarkably intelligent—bears little resemblance to the sluggish giants imagined by Victorian scientists. The story of this transformation reminds us that science progresses not just through discoveries but through the willingness to question established paradigms when evidence demands it. The dinosaurs we now understand inhabited ancient Earth were far more fascinating, complex, and bird-like than the giant lizards once imagined, making their true story even more remarkable than the misconceptions that preceded it.