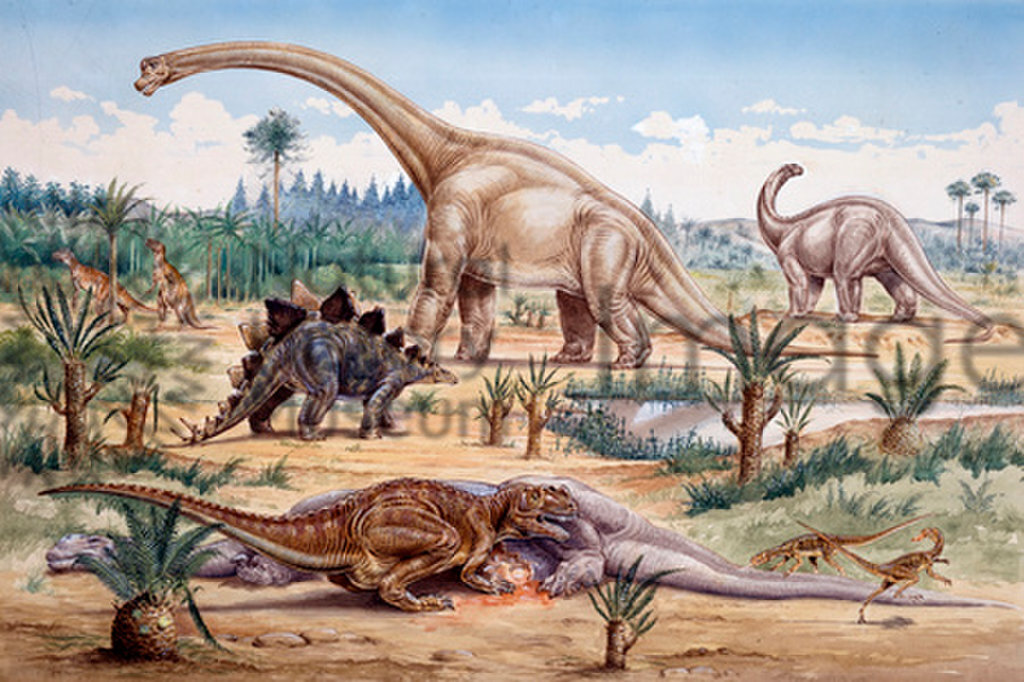

The ancient world was a dynamic place where the very ground beneath dinosaurs’ feet was constantly shifting. As continental landmasses split, merged, and transformed through tectonic activity, they created crucial pathways that influenced dinosaur migration patterns and ultimately shaped the course of evolutionary history. The relationship between plate tectonics and dinosaur distribution offers fascinating insights into how Earth’s geological processes directed biological diversity during the Mesozoic Era. This intricate dance between shifting continents and dinosaur populations reveals a complex story of adaptation, isolation, and expansion that continues to captivate paleontologists and geologists alike.

The Mesozoic Stage: Setting the Scene for Dinosaur Migration

When dinosaurs first appeared during the Late Triassic period, approximately 230 million years ago, Earth’s continents were united in the supercontinent Pangaea. This massive landmass created an uninterrupted terrain where early dinosaurs could potentially range across much of the planet without encountering oceanic barriers. The climate zones stretched continuously from pole to pole, creating bands of habitat that encouraged migration along similar environmental conditions.

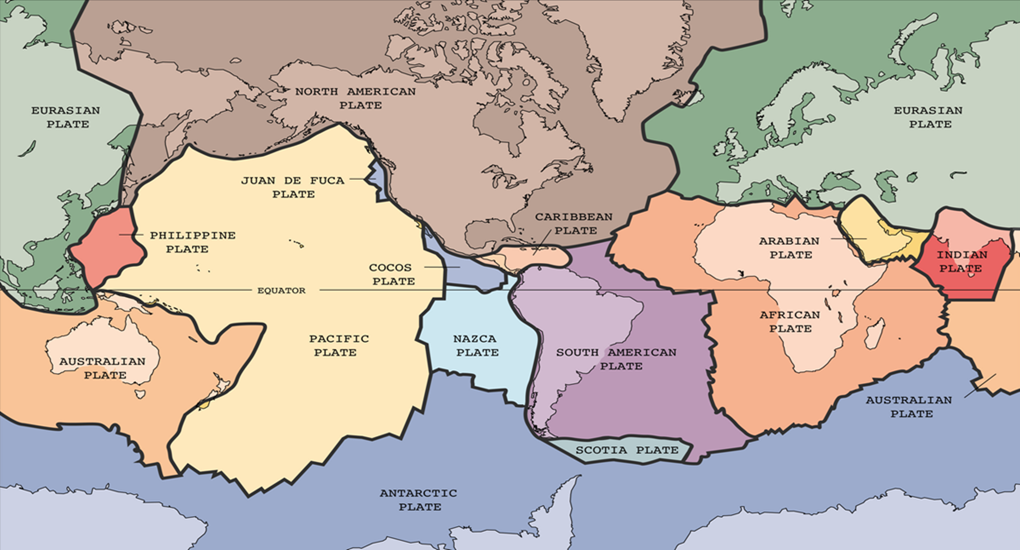

As the Mesozoic progressed through the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, Pangaea gradually fragmented, first into Laurasia (northern continents) and Gondwana (southern continents), and then into configurations more recognizable today. These tectonic shifts fundamentally altered the migratory possibilities for dinosaur species, creating both opportunities and barriers that would influence their distribution patterns for millions of years.

Pangaea: The Original Dinosaur Highway

Pangaea served as the first great dinosaur highway, allowing for widespread distribution of early dinosaur species across what would eventually become separate continents. The supercontinent’s integrity during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods (about 230-180 million years ago) meant that dinosaurs like the small, swift-footed Coelophysis or the larger Plateosaurus could potentially traverse vast distances without encountering major geographical barriers. Fossil evidence supports this continental connectivity, with similar dinosaur species appearing in regions that would later become widely separated.

For example, fossils of the prosauropod Massospondylus have been found in areas that would later become South Africa, Argentina, and parts of North America, demonstrating how Pangaea facilitated dinosaur dispersal. This period of continental unity created the foundation for dinosaur distribution patterns that would later be altered by tectonic separation.

The Great Rift: When Continents Began to Separate

Around 180 million years ago, during the Mid-Jurassic period, Pangaea began its significant fragmentation as tectonic forces pulled the supercontinent apart. This initial split created Laurasia in the north (containing what would become North America, Europe, and Asia) and Gondwana in the south (comprising future South America, Africa, India, Australia, and Antarctica). The formation of the Tethys Sea between these landmasses created the first major oceanic barrier to dinosaur migration, fundamentally altering previously established movement patterns.

As this rift expanded, dinosaur populations on either side began to evolve independently, responding to their increasingly distinct environments and ecological pressures. The timing of this separation coincides with noticeable divergences in dinosaur lineages, with unique groups beginning to appear in the northern and southern hemispheres. These early continental divisions laid the groundwork for the distinctive dinosaur faunas that would later characterize different regions of the globe.

Land Bridges: Temporary Connections in a Changing World

Even as the continents drifted apart, temporary land bridges periodically formed due to fluctuating sea levels and ongoing tectonic activity, creating crucial migration corridors for dinosaurs. These ephemeral connections allowed for intermittent exchanges between otherwise isolated dinosaur populations, contributing to the complex patterns of dinosaur distribution observed in the fossil record. The Bering land bridge between Asia and North America, for example, existed intermittently throughout the Late Cretaceous, enabling faunal exchanges that explain the similarities between dinosaur species on these continents.

Similarly, connections between South America and Africa persisted longer than many other Gondwanan links, allowing for continued migration between these regions well into the Early Cretaceous. These temporary pathways created by tectonic positioning and sea level changes acted as intermittent highways for dinosaur dispersal, resulting in the mosaic pattern of dinosaur distribution that paleontologists work to unravel today.

The North Atlantic Corridor: A Critical Migration Route

As Laurasia began breaking apart, a crucial migration corridor existed across what would become the North Atlantic Ocean, connecting North America with Europe well into the Early Cretaceous period. This land bridge, sometimes called the “North Atlantic Land Bridge,” persisted even as other continental connections dissolved, creating a vital pathway for dinosaur movement between these regions for millions of years. Evidence for this connection can be seen in the striking similarities between dinosaur fossils found in eastern North America and western Europe from this time period.

For instance, the Early Cretaceous dinosaur Iguanodon has been discovered on both sides of the modern Atlantic, suggesting a shared fauna facilitated by this tectonic configuration. The presence of this corridor helps explain why North American and European dinosaur communities remained relatively similar during this time while both became increasingly distinct from their southern counterparts in Gondwana.

The Gondwanan Fragmentation and Southern Dinosaur Diversity

The breakup of Gondwana proceeded more gradually than that of Laurasia, with South America, Africa, India, Australia, and Antarctica separating in stages throughout the Cretaceous period. This sequential fragmentation created a fascinating pattern of dinosaur endemism, with unique species evolving in isolation on each landmass. Africa separated relatively early, while South America and Antarctica remained connected until nearly the end of the Mesozoic, explaining certain similarities in their dinosaur faunas.

Perhaps the most dramatic example of isolation-driven evolution occurred in India, which broke away and drifted northward as an island continent for over 30 million years before colliding with Asia. This isolation allowed for the development of highly specialized dinosaur species, though unfortunately, India’s fossil record from this period remains relatively sparse. The complex choreography of Gondwana’s breakup created a natural experiment in dinosaur evolution, with each fragment developing its own distinct dinosaur communities.

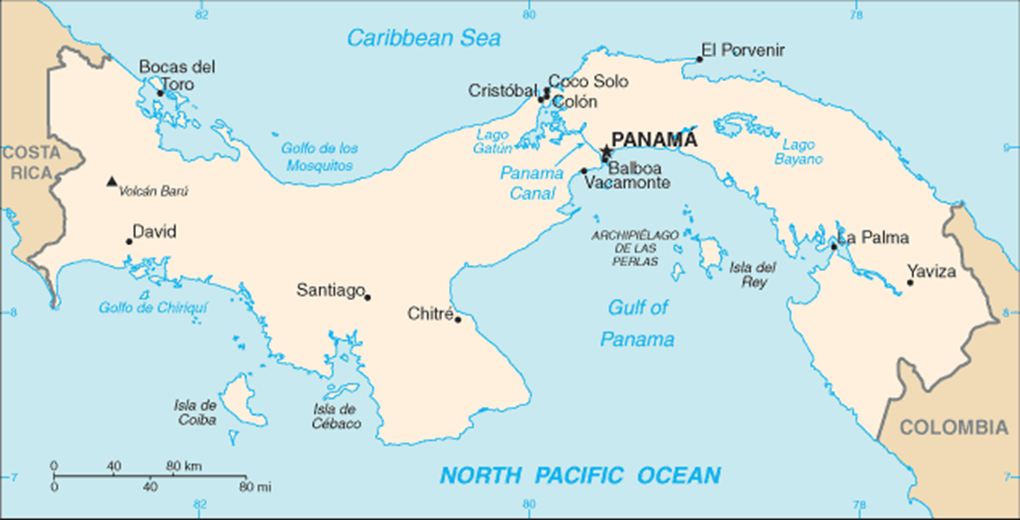

Central American Land Bridge: Connecting North and South

The isolation between North and South America created by tectonic separation had profound effects on dinosaur evolution, particularly during the Late Cretaceous period. For much of this time, the two continents remained separated by a substantial marine barrier, leading to distinct dinosaur faunas developing in each region. South America, in particular, became home to unique dinosaur groups like the bizarre long-necked titanosaurs and the predatory abelisaurids that evolved in isolation from their northern counterparts.

Intermittent land connections may have existed, however, as evidenced by some degree of faunal overlap that suggests occasional migration opportunities. These connections were likely sporadic and limited, creating filters that allowed only certain dinosaur groups to cross between the Americas. The complex relationship between these two continental landmasses, mediated by shifting tectonic configurations, contributed significantly to the distinctive character of North and South American dinosaur communities in the late Mesozoic.

Isolation and Evolution: The Australian Example

Perhaps no continent better exemplifies the evolutionary consequences of tectonic isolation than Australia, which separated from Antarctica approximately 85 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous. This separation created a natural laboratory for dinosaur evolution as Australian dinosaur populations became completely cut off from their counterparts elsewhere in the world.

The fossil evidence, though limited, reveals a fascinating assemblage of unique dinosaurs that evolved in this isolated context. The polar dinosaurs of Australia, adapted to the cold, dark winters of the high southern latitudes, developed specialized adaptations such as enhanced vision and possibly even warm-blooded metabolisms to survive in their challenging environment.

Discoveries at sites like Dinosaur Cove in Victoria have revealed small, agile dinosaurs that thrived in this isolated ecosystem. Australia’s tectonic separation provides a compelling example of how plate movements directly influenced dinosaur evolution by creating conditions for allopatric speciation on a continental scale.

The Asian Connection: How Tectonic Activity Shaped Dinosaur Diversity

Asia’s complex tectonic history during the Mesozoic created a dynamic setting for dinosaur evolution and migration. Throughout much of the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, parts of Asia remained relatively isolated, while other regions maintained connections with Europe and intermittently with North America via the Bering land bridge. This semi-isolation, combined with periodic connectivity, created ideal conditions for both evolutionary innovation and faunal exchange. The varied topography resulting from tectonic activity – including mountain formation, basin development, and changing coastlines – generated diverse habitats that fostered exceptional dinosaur diversity.

This helps explain why Asia boasts such remarkable dinosaur fossils, from the feathered dinosaurs of China’s Liaoning Province to the dinosaur nesting grounds of Mongolia’s Gobi Desert. The continent’s shifting relationship with other landmasses allowed it to serve as both an evolutionary cradle where unique dinosaur lineages could develop and as a crossroads where different dinosaur communities could intermingle during periods of connection.

Climate Zones and Tectonic Movement: The Double Barrier

Tectonic plate movements not only created physical barriers to dinosaur migration through continental separation but also generated climate barriers by altering global weather patterns and repositioning landmasses across different latitudes. As continents shifted position relative to the equator, dinosaur populations had to adapt to changing climatic conditions or migrate to maintain their preferred environment.

This created what paleontologists sometimes call a “double barrier” effect, where both physical geography and climate zones dictated dinosaur distribution patterns. For example, as India moved northward from its original position in the southern hemisphere, dinosaurs living there experienced progressively warmer conditions, forcing adaptation or extinction.

Similarly, parts of what is now Europe shifted from tropical to more temperate latitudes during the Mesozoic, altering the composition of dinosaur communities. These tectonic-driven climate shifts acted as powerful evolutionary forces, selecting for dinosaurs that could either adapt to changing conditions or successfully migrate along with their preferred climate zone.

Extinction and Tectonic Position: The K-Pg Boundary Event

The position of the continents at the end of the Cretaceous period may have influenced how the asteroid impact that caused the K-Pg extinction event affected dinosaur populations across the globe. When the Chicxulub impactor struck what is now Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula approximately 66 million years ago, the arrangement of the continents and oceans influenced the distribution of its devastating effects. The North American continent, closest to the impact site, likely experienced the most immediate and severe consequences.

In contrast, some regions more distant or protected by geographical features might have experienced slightly delayed or somewhat diminished effects, potentially explaining certain patterns in the fossil record. Recent research suggests that some dinosaur populations were already under stress due to climate changes related to intense volcanic activity in the Deccan Traps of India – itself the result of tectonic processes as India moved northward. The complex interaction between the continental configuration created by plate tectonics and the catastrophic impact event ultimately determined which ecosystems were most severely affected and which, if any, might have provided temporary refugia during this global catastrophe.

Modern Discoveries: How Plate Tectonics Continues to Reveal Dinosaur Secrets

Today’s continental arrangement, the product of millions of years of tectonic movement since the Mesozoic Era, directly influences where paleontologists can search for dinosaur fossils and what kinds of discoveries they might make. Understanding ancient continental connections helps scientists predict where to look for similar dinosaur species across now-separated landmasses.

Modern techniques in paleogeography allow researchers to reconstruct ancient continental positions with increasing precision, revealing potential migration corridors that explain puzzling patterns in the fossil record. For example, recent discoveries of similar dinosaur species in Madagascar and India have confirmed their proximity during the Late Cretaceous before India’s northward journey.

Additionally, the study of how modern continents have shifted since the Mesozoic helps paleontologists account for the taphonomic bias in the fossil record – the uneven preservation and discovery of fossils due to geological processes. Areas that have experienced significant uplift or erosion since the Mesozoic might have lost much of their fossil record, while others where sediments have accumulated and been preserved yield richer findings, creating a complex puzzle that researchers continue to piece together.

Future Research: The Next Frontier in Understanding Dinosaur Migration

Emerging technologies and interdisciplinary approaches are opening new frontiers in the study of how tectonic movements influenced dinosaur migration patterns. Advanced techniques in geochemical analysis, including isotope studies of fossil teeth and bones, allow scientists to track the movement patterns of individual dinosaurs during their lifetimes, potentially revealing seasonal migrations or responses to changing environments caused by tectonic shifts.

Sophisticated computer modeling combining climate simulations with reconstructed ancient landscapes enables researchers to predict viable migration corridors and habitat distributions across shifting continental configurations. Genetic analysis of modern birds, the living descendants of theropod dinosaurs, provides insights into ancient dispersal patterns that may reflect continental connections that existed during the Mesozoic.

Perhaps most excitingly, ongoing fossil discoveries in previously unexplored regions continue to fill crucial gaps in our understanding of dinosaur distribution, sometimes confirming predicted patterns based on tectonic reconstructions and sometimes challenging existing models, driving the field forward. As these various approaches converge, our understanding of how Earth’s restless crust directed the movements of its most spectacular inhabitants continues to deepen and evolve.

Conclusion

The story of dinosaur migration across Earth’s ever-shifting surface exemplifies the profound interconnection between geological and biological processes. As tectonic plates divided and united continents throughout the Mesozoic Era, they created an ever-changing landscape that dinosaurs navigated for over 165 million years. The patterns of dinosaur diversity we observe in the fossil record—from widespread cosmopolitan families to highly specialized endemic species—reflect this dynamic tectonic history.

By studying the relationship between continental drift and dinosaur distribution, scientists gain insights not only into the lives of these fascinating creatures but also into the fundamental processes that shape biodiversity across geological timescales. The ancient pathways carved by tectonic activity directed the flow of dinosaur populations, creating evolutionary opportunities and challenges that ultimately shaped the magnificent diversity of the dinosaur dynasty.