Dinosaurs have long captured our imagination as magnificent creatures from a distant past, seemingly wiped out by a catastrophic asteroid impact approximately 66 million years ago. However, contrary to popular belief, dinosaurs aren’t entirely extinct. This might sound surprising given that we don’t see Tyrannosaurus rex or Brachiosaurus roaming our landscapes today, but the scientific reality tells a more nuanced story. Modern birds, from the humble sparrow to the majestic eagle, are direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs, representing the continuation of the dinosaur lineage in our contemporary world. This article explores the fascinating evolutionary connection between ancient dinosaurs and modern birds, revealing why paleontologists and biologists consider birds to be living dinosaurs, and why the extinction narrative we’ve commonly accepted deserves reconsideration.

The Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction Event: What Really Happened

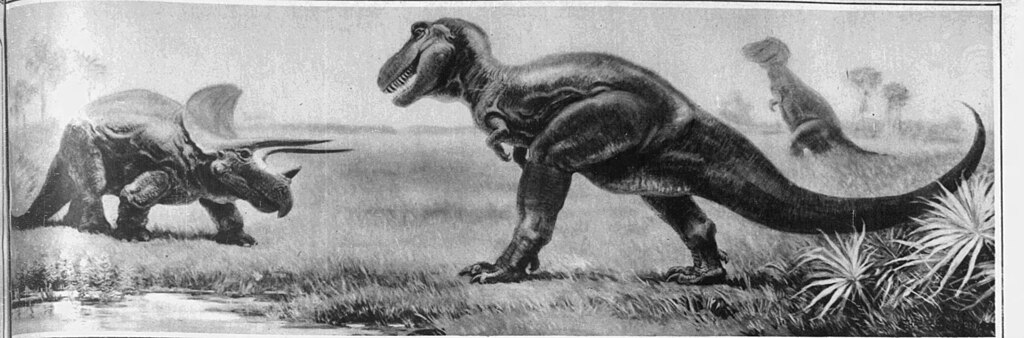

The asteroid impact that struck Earth approximately 66 million years ago near what is now the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico triggered one of the most devastating mass extinctions in our planet’s history. This cataclysmic event, known as the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction, eliminated approximately 75% of all species on Earth, including all non-avian dinosaurs. The impact created a global catastrophe of wildfires, tsunamis, and climate disruption that drastically altered Earth’s ecosystems. However, this extinction wasn’t as complete as commonly portrayed in popular media. While the large, iconic dinosaurs like Triceratops and Velociraptor did indeed perish, one lineage of dinosaurs—the small, feathered theropods—managed to survive this apocalyptic scenario. These survivors would eventually evolve into the thousands of bird species we recognize today, carrying the dinosaur legacy forward through time in a remarkable evolutionary journey.

The Evolutionary Relationship Between Birds and Dinosaurs

The connection between birds and dinosaurs represents one of paleontology’s most compelling evolutionary narratives. Modern birds belong to a group called avian dinosaurs, and they evolved from a lineage of theropod dinosaurs—the same group that included predators like Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus. This relationship wasn’t always obvious or accepted by the scientific community. When Thomas Henry Huxley first proposed the dinosaur-bird connection in the 1860s, following the discovery of Archaeopteryx, his ideas were met with skepticism. It wasn’t until the late 20th century, with the discovery of numerous feathered dinosaur fossils from China’s Liaoning Province, that the evidence became overwhelming. These fossils revealed dinosaurs with preserved feathers, wishbones, and other avian features, effectively bridging the gap between non-avian dinosaurs and modern birds. Today, the scientific consensus firmly establishes birds as a specialized group of theropod dinosaurs that survived the K-Pg extinction event, making them living dinosaurs by proper taxonomic classification.

Archaeopteryx: The Iconic Missing Link

Discovered in 1861 in southern Germany, Archaeopteryx lithographica represents one of paleontology’s most significant finds and a crucial piece of evidence in understanding the dinosaur-bird connection. This 150-million-year-old fossil from the Late Jurassic period displays an extraordinary combination of reptilian and avian features, earning it the status of a transitional fossil or “missing link.” Archaeopteryx possessed the feathers and wishbone of a bird, yet retained many dinosaurian characteristics including teeth, a long bony tail, and three clawed fingers on each wing. The fossil emerged at a pivotal time, just two years after Darwin published “On the Origin of Species,” providing compelling evidence for his theory of evolution. Though not a direct ancestor of modern birds, Archaeopteryx offers a snapshot of the evolutionary transition occurring between non-avian dinosaurs and birds. Its discovery fundamentally altered our understanding of avian origins and provided the first tangible evidence that birds evolved from dinosaur ancestors rather than representing a separate lineage of vertebrates.

The Feathered Dinosaurs of Liaoning

The fossil beds of Liaoning Province in northeastern China have yielded some of the most spectacular paleontological discoveries of the past few decades, revolutionizing our understanding of dinosaur evolution and appearance. Beginning in the 1990s, these exceptional fossils revealed something remarkable: numerous non-avian dinosaurs preserved with clear impressions of feathers. Discoveries like Sinosauropteryx, the first non-avian dinosaur confirmed to have feathers, and Microraptor, a small dinosaur with four wings, fundamentally changed how scientists viewed dinosaur appearance and physiology. The fine-grained sedimentary deposits of Liaoning preserved these delicate structures due to rapid burial in volcanic ash, capturing details that would normally decompose before fossilization could occur. These fossils demonstrated that feathers evolved in dinosaurs long before the origin of flight, likely serving functions related to display, insulation, or brooding behavior before being co-opted for aerial locomotion. The Liaoning fossils effectively erased the clear distinction between birds and dinosaurs, revealing a spectrum of features rather than a sharp dividing line, and provided irrefutable evidence that birds are indeed living dinosaurs.

Cladistics: How Scientists Classify Birds as Dinosaurs

The classification of birds as dinosaurs is not merely a semantic choice but reflects the rigorous application of cladistic taxonomy, the predominant system biologists use to organize living things based on evolutionary relationships. Cladistics groups organisms according to their shared derived characteristics, creating nested sets of related organisms called clades. In this system, a taxonomic group must include all descendants of a common ancestor to be considered valid—a principle known as monophyly. When scientists apply cladistic analysis to dinosaurs and birds, the evidence unequivocally places birds within the theropod dinosaur group. This means that, taxonomically speaking, birds are a specialized subgroup of dinosaurs in the same way that humans are a specialized subgroup of primates. To classify dinosaurs in a way that excludes birds would create a “paraphyletic” group—one that includes some but not all descendants of a common ancestor—which violates the principles of modern systematic biology. Therefore, from a strictly scientific perspective, the common notion that dinosaurs are extinct is inaccurate; rather, most dinosaur lineages went extinct while the avian dinosaur lineage persisted and diversified into the approximately 10,000 bird species alive today.

Anatomical Evidence: Dinosaurian Features in Modern Birds

Modern birds retain numerous anatomical features that reveal their dinosaurian heritage, providing tangible evidence of their evolutionary relationship to extinct dinosaur species. The skeletal structure of birds contains many hallmark dinosaurian characteristics, particularly from their theropod ancestors. Birds possess a furcula (wishbone), a feature first evolved in theropod dinosaurs, as well as a specialized wrist joint that allows for the folding of wings—a joint structure initially evolved in non-flying dinosaurs. The three-toed foot structure of birds mirrors that of their dinosaur ancestors, with many similar proportions and arrangements. Even the highly modified skulls of modern birds retain evidence of their dinosaurian origins, with similarities in skull openings and bone arrangements. Perhaps most tellingly, birds develop through embryonic stages that reveal ancestral features that disappear before hatching, including hand digits that fuse to form the wing tip and tail vertebrae that fuse into the pygostyle. These anatomical similarities represent not convergent evolution but homologous structures—features derived from a common ancestor—providing a physical record of birds’ evolutionary history as the last surviving dinosaur lineage.

Behavioral Links: Dinosaur Behaviors That Persist in Birds

The behavioral connections between non-avian dinosaurs and modern birds provide another compelling line of evidence for their evolutionary relationship. Many distinctive bird behaviors have roots in their dinosaurian ancestors, revealed through fossil evidence and comparative studies. Nesting and parental care behaviors seen in modern birds appear to have evolved in theropod dinosaurs, as evidenced by fossils showing adult dinosaurs brooding over nests, such as the oviraptorid dinosaur discovered in Mongolia sitting atop a clutch of eggs. The complex courtship displays and social behaviors observed in many bird species likely evolved from similar behaviors in their dinosaur ancestors, suggested by features like the elaborate crests and feather displays found in fossil theropods. Even the distinctive head-bobbing gait of chickens and other birds represents a vestigial movement pattern inherited from their dinosaurian forebears. Sleep postures in modern birds, who often tuck their heads under their wings, mirror positions observed in exceptionally preserved dinosaur fossils. These behavioral continuities between non-avian dinosaurs and birds reinforce their close evolutionary relationship, demonstrating that many characteristic avian behaviors are actually dinosaurian behaviors that have persisted and evolved over millions of years.

Respiratory Systems: The Dinosaur Breathing Legacy

One of the most remarkable physiological connections between birds and their dinosaur ancestors lies in their highly specialized respiratory systems. Modern birds possess a unique respiratory apparatus featuring air sacs that extend into hollow bones, creating a one-way flow of air through the lungs that allows for efficient oxygen extraction even at high altitudes where oxygen is scarce. This system differs dramatically from the bidirectional breathing of mammals and most other vertebrates. Fossil evidence reveals that non-avian theropod dinosaurs possessed similar respiratory adaptations, including hollow, air-filled bones (pneumaticity) and likely the same system of air sacs. CT scans of theropod vertebrae show pneumatic features remarkably similar to those of modern birds, suggesting they shared this efficient breathing mechanism. This respiratory system probably contributed to the active, high-metabolism lifestyle of theropod dinosaurs, providing the oxygen necessary for sustained activity. The presence of this specialized respiratory apparatus in both birds and non-avian theropods represents a profound physiological continuity, further confirming that birds didn’t just evolve from dinosaurs—they inherited complex internal systems that remain essentially dinosaurian in nature, allowing them to become the remarkably successful aerial vertebrates we see today.

The Evolution of Flight: From Dinosaur to Bird

The evolution of powered flight represents one of the most significant transitions in vertebrate evolution, transforming ground-dwelling theropod dinosaurs into the aerial masters we recognize as birds today. This transition didn’t occur as a sudden leap but through incremental evolutionary steps over millions of years. The pathway likely began with small, feathered dinosaurs using their limbs for purposes other than flight—perhaps for balance while running, display during courtship, or insulation for thermoregulation. Fossil evidence suggests that the capacity for limited gliding may have evolved in some dinosaur lineages, as seen in the four-winged Microraptor, which possessed flight feathers on both its front and hind limbs. From these intermediate stages, true powered flight eventually evolved in the ancestors of modern birds, accompanied by numerous anatomical modifications including a keeled sternum for flight muscle attachment, lightweight hollow bones, and modified forelimbs. The evolution of the alula, or “bastard wing”—a small projection on the wing formed by the first digit—provided crucial flight control, allowing for slower flight speeds and more precise landing capabilities. This evolutionary sequence from terrestrial dinosaur to aerial bird represents not a break in the dinosaur lineage but its extraordinary diversification into a new ecological niche, with birds continuing the dinosaurian evolutionary story into the present day.

Dinosaurs of the Present: The Most Dinosaur-Like Birds Today

While all modern birds are technically dinosaurs, some species exhibit characteristics that more visibly reflect their dinosaurian heritage, making them particularly evocative of their ancient ancestors. The cassowary, a flightless bird native to New Guinea and northeastern Australia, features prominently in this category with its large size, powerful legs, and dagger-like claws capable of inflicting serious wounds—reminiscent of the fearsome raptors of the Mesozoic era. The prehistoric-looking shoebill stork of Africa, with its massive bill and imposing stature, evokes images of ancient creatures from a bygone age. Hoatzins, sometimes called “prehistoric turkeys,” possess curved claws on their wings as juveniles that they use to climb trees, mirroring a feature found in Archaeopteryx and other early avian dinosaurs. The secretary bird of Africa, with its terrestrial hunting style and method of stamping prey to death with powerful kicks, displays hunting behaviors potentially similar to those of some theropod dinosaurs. Even common birds like chickens reveal their dinosaurian nature when observed closely—their scaly legs, predatory head movements, and territorial behaviors all echo their theropod ancestry. These living dinosaurs provide us with a tangible connection to the distant past, walking among us as the last survivors of a lineage that has dominated terrestrial ecosystems for over 230 million years.

Scientific Consensus: What Paleontologists Really Think

The scientific consensus regarding birds as living dinosaurs has solidified dramatically over the past few decades, representing one of paleontology’s most profound paradigm shifts. Today, virtually all professional paleontologists accept that birds are theropod dinosaurs, constituting the only dinosaur lineage to survive the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. This wasn’t always the case—throughout much of the 20th century, many scientists maintained that birds represented a separate evolutionary line distinct from dinosaurs, perhaps evolving from earlier archosaurs. The accumulation of fossil evidence, particularly from the 1990s onward, rendered this position untenable as hundreds of shared anatomical features between birds and non-avian theropods came to light. Renowned paleontologists like Jack Horner, Luis Chiappe, and Xu Xing have been at the forefront of establishing this evolutionary continuity through extensive fieldwork and anatomical studies. The scientific literature now consistently refers to birds as avian dinosaurs and their extinct relatives as non-avian dinosaurs, reflecting this taxonomic reality. This consensus extends beyond academia into major natural history museums worldwide, where modern exhibitions consistently present birds as the living descendants of the dinosaur lineage, educating the public about this remarkable evolutionary connection and helping to correct the common misconception that dinosaurs disappeared completely 66 million years ago.

Popular Misconceptions: Why We Think of Dinosaurs as Extinct

The persistent public perception that dinosaurs are completely extinct stems from several interrelated factors that have shaped our cultural understanding of these ancient creatures. Historical context plays a significant role—when dinosaur fossils were first scientifically described in the 19th century, their relationship to birds wasn’t yet understood, establishing an early narrative of dinosaurs as entirely extinct beasts from a prehistoric world. Popular media has powerfully reinforced this misconception through films, books, and documentaries that typically portray dinosaurs as fundamentally different from modern animals, creating a conceptual divide between “dinosaurs” and “birds” that doesn’t reflect biological reality. Educational simplification contributes as well, with elementary education often teaching dinosaur extinction as a complete event rather than explaining the more nuanced survival of the avian lineage. Language usage perpetuates the misconception, as we colloquially use “dinosaur” to refer only to non-avian dinosaurs while categorizing birds separately, despite their taxonomic relationship. Even museum displays have historically contributed by physically separating dinosaur fossils from bird exhibits, though this practice has changed in many modern institutions. These factors collectively create a disconnect between scientific understanding and public perception, reinforcing the inaccurate idea that dinosaurs represent an entirely vanished group rather than a largely extinct but partially surviving lineage that continues to thrive in the form of modern birds.

Beyond Birds: Other Living Dinosaur Relatives

While birds stand as the only living dinosaurs in the strict taxonomic sense, other modern animals share evolutionary connections with dinosaurs as fellow members of the larger reptile group Archosauria. Crocodilians—including crocodiles, alligators, caimans, and gharials—represent the closest living relatives to dinosaurs aside from birds. The archosaur lineage diverged into two major branches during the Triassic period: one leading to crocodilians and the other to dinosaurs (including birds). This makes crocodilians the closest living cousins to all dinosaurs, sharing a more recent common ancestor with them than with other reptiles like lizards and snakes. Some anatomical features found in both crocodilians and birds likely existed in their common archosaurian ancestors, including four-chambered hearts, specialized ankle joints, and similar nest-building and parental care behaviors. Tuataras, the ancient reptiles native only to New Zealand, represent another living connection to the age of dinosaurs, though more distantly related than crocodilians.