The fossil bones of dinosaurs can tell us only so much—but paired with biomechanical models, trackways, and comparisons to living animals, scientists have attempted to estimate how fast these extinct giants (or sprinters) could run. While no dinosaur likely outran the modern cheetah, some may have matched or even exceeded the speeds of today’s fast mammals like greyhounds, antelopes, or ostriches.

In this article we explore ten dinosaur or near-dinosaur species that, according to current research and modeling, might have achieved running speeds rivaling or surpassing certain modern animals. For each, we’ll examine the evidence, the assumptions behind speed estimates, and how credible such claims are in light of physical constraints.

(Caution: Dinosaur speed estimates often vary widely. Trackway evidence, muscle reconstructions, and scaling laws all bring uncertainty.)

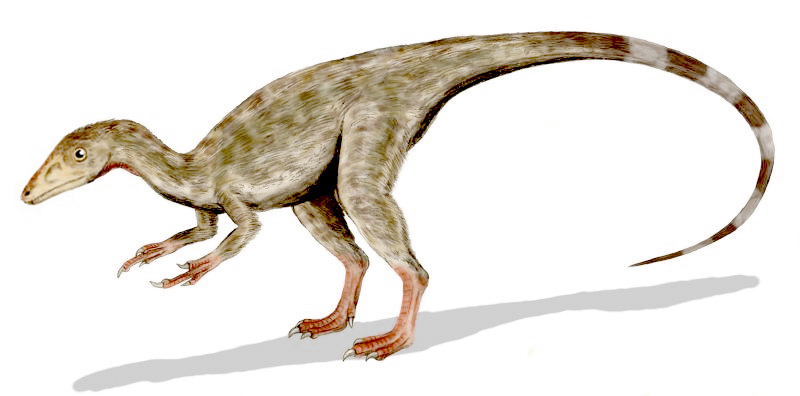

1. Compsognathus

Compsognathus was a small theropod (about 1 m long, light in build) that often appears in lists of “fastest dinosaurs.” Some researchers have estimated its running speed at ~65 km/h (≈ 18 m/s) based on limb proportions and comparative scaling. Such a speed would put it in the same ballpark as a fast hare or certain small ungulates.

However, these high estimates should be treated skeptically. Models relying purely on proportional scaling may overestimate performance due to ignoring muscle power, mechanical stresses, and energy limits. Still, Compsognathus remains a strong candidate for one of the more agile and speedy dinosaurs known.

2. Gallimimus

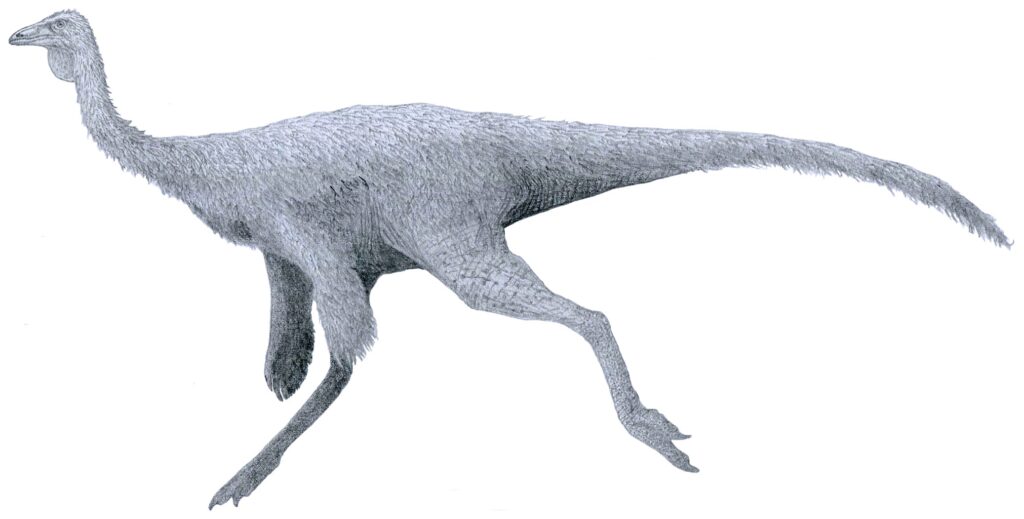

Gallimimus (an ornithomimid) is often described as the “ostrich mimic.” Its long legs and cursorial build suggest specialization for running. Some estimates place its top speed between 42 and 56 km/h (≈ 29–34 mph). That range is comparable to the sustained running speeds of modern hoofed mammals over short distances.

Because Gallimimus is moderately large but still light relative to giant theropods, its morphology (long distal leg segments, reduced mass) helps the plausibility of these speeds. But the uncertainty remains: factors such as tendon elasticity, stride frequency, and muscle physiology are not preserved in fossils.

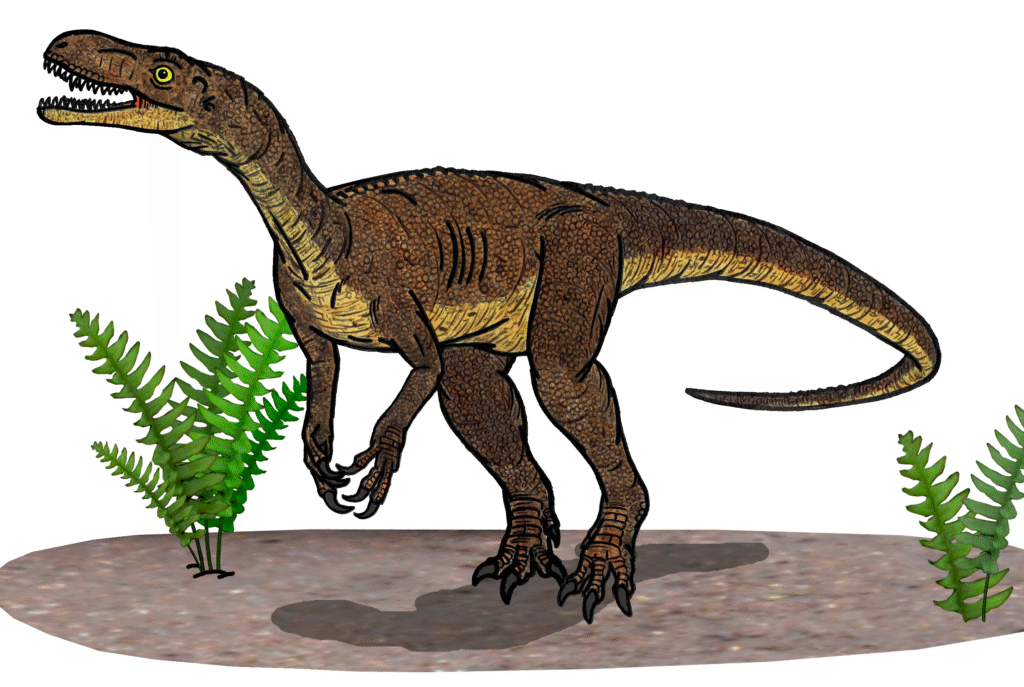

3. Dryosaurus

Dryosaurus, a modestly sized ornithopod from the Late Jurassic, is sometimes cited in speed compendiums. One source gives an estimate ~43 km/h. While not as extreme as the fastest theropods, this speed would still rival those of modern medium-sized mammals.

Dryosaurus’s light frame, long limbs, and bipedal ability (at least when running) likely contributed to its agility. However, it is less frequently studied for locomotor performance compared to predatory theropods, making its speed estimate less constrained in scientific literature.

4. Eodromaeus

Eodromaeus was an early dinosaur (from the Triassic) with a lightweight build and relatively long hindlimbs. Some estimates (e.g. by Paul Sereno) propose it could run around 32 km/h (≈ 20 mph). Though not extreme, that speed would surpass many modern animals of similar size, like foxes or coyotes under some conditions.

What makes Eodromaeus interesting is its position early in dinosaur evolution. If it was already specialized for running, this suggests that speed was an important ecological trait from deep time. That said, the margin of error is substantial, as muscle anatomy and topology remain unknown.

5. Nanotyrannus (or juvenile Tyrannosaur)

Nanotyrannus is controversial—some paleontologists argue it is a juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex—but its limb proportions suggest it may have been more gracile (lighter built) and potentially faster than its adult kin. The University of Alberta researchers, for example, proposed that Nanotyrannus might have been among the speedier theropods in its realm.

If its speed exceeded even that of adult T. rex, it might have surpassed modern large terrestrial predators in agility. However, because its taxonomic status is unresolved, the speed claims carry that extra layer of uncertainty.

6. Tyrannosaurus rex

While popular culture often depicts T. rex as a lightning-fast predator, many biomechanical studies caution against that image. Recent reconstructions place its top running speed at somewhere between 20–40 km/h (12–25 mph). Some older models had argued for much higher speeds, but those tend to strain credulity when one considers bone strength and mass.

Still, even if T. rex could only achieve ~25–30 mph in ideal bursts, that compares favorably with many modern large predators (wolves, large cats in less than top form). Its stride length and muscle leverage might have allowed short sprints, though sustaining them would strain physiology.

7. Velociraptor

Velociraptor is often portrayed in fiction as a “raptor” pack hunter, and some authors have estimated its speed in the range of ~10.8 m/s (≈ 39 km/h) based on limb proportions in biomechanical models. Compared to many modern predators, that’s respectable for its size.

However, that number is derived from idealized conditions. In reality, turning, substrate, and muscle fatigue would likely reduce effective speed. Still, as a mid-sized theropod, Vircioraptor probably had a good burst speed relative to similarly sized modern animals.

8. Allosaurus

Allosaurus, a large Jurassic predator, appears in some speed-estimating tables: one modeling effort suggests ~9.4 m/s (~34 km/h). Though that speed is lower than for smaller theropods, it is still comparable to modern large mammals (e.g., elk or moose briefly can reach ~55 km/h).

But for a predator of Allosaurus’s size, sustaining top speed would be physiologically taxing. Joint stresses, muscle energetics, and skeletal robustness impose constraints. Many scientists thus view such speed estimates as upper bounds rather than realistic sustained performance.

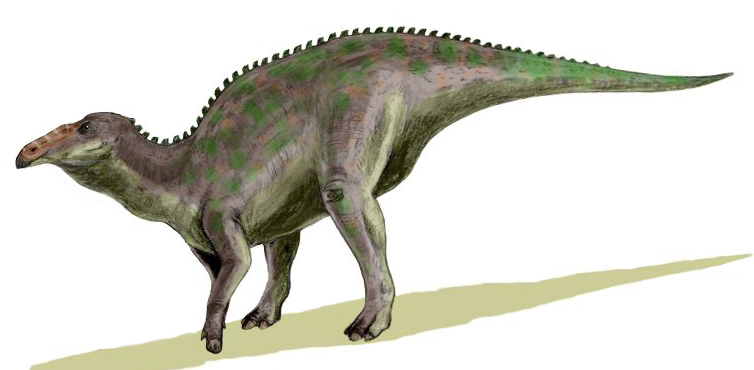

9. Edmontosaurus

Edmontosaurus, a hadrosaurid, is not a predator but has been included in locomotor modeling studies. Some simulations suggest it could reach ~45 km/h under certain bipedal running or galloping gaits. While that speed is not extreme compared to theropods, it still matches or exceeds the jogging or sprinting speeds of many large modern mammals.

Because Edmontosaurus likely alternated between quadrupedal and bipedal movement, the estimated speed pertains to its capacity in high-velocity bipedal motion—a conditional exercise based on ideal morphometrics.

10. Struthiomimus (or related ornithomimids)

Struthiomimus and its close kin (ornithomimids) are often grouped with Gallimimus as among the fastest dinosaurs. Though fewer precise estimates exist, their morphology (long legs, lightweight bodies, reduced forelimbs) strongly suggests high cursorial capacity. Some sources on “fastest dinosaurs” lists include Struthiomimus alongside Gallimimus.

If its top speed approached 50 km/h or more, it could outperform many modern medium mammals over short bursts. As with Gallimimus, the constraint is how much muscle, tendon elasticity, and gait dynamics are factored into models.

Estimating dinosaur running speeds is a complex interplay of bone geometry, muscle inference, trackway data, and scaling models. While none of the dinosaurs above likely rival the top speed of the modern cheetah (~100–120 km/h), some could plausibly outrun or match many extant mammals in their ecological niches. As new fossils and better modeling methods arrive, our picture of dinosaur sprinting may sharpen—and perhaps surprise us yet again.