From the earliest feathery gliders to tentative flappers bridging ground and sky, the story of dinosaur flight is one of innovation, dead ends, and evolutionary experimentation. Long before birds ruled the air, various dinosaur lineages explored aerial locomotion in forms both graceful and awkward. Some never quite mastered powered flight, instead gliding between tree branches; others may have flapped in limited bursts. The fossils of these creatures offer tantalizing clues about how flight evolved and diversified in the dinosaur lineage.

In this article, we spotlight six remarkable dinosaur (or near-dinosaur) taxa that show evidence of gliding or possible flight. Each of these species occupies a place in the paleontological debate—are they true flyers, gliders, or somewhere in between? Their anatomy, ecology, and the context of their discoveries help us trace the evolutionary steps that ultimately led to modern birds.

1. Microraptor

Microraptor is perhaps the poster child for dinosaurian flight experiments. This small, four-winged dromaeosaurid from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China, bore long pennaceous feathers not just on its arms and tail, but also along its legs, creating what appear to be hind wings. Early studies proposed that Microraptor might glide in a “biplane” configuration, launching from branches and swooping among trees in a controlled arc. More recent work suggests that Microraptor may have been capable of limited powered flight, or at least wing-assisted locomotion.

Its anatomical features—feathered limbs, an elongated tail with aerodynamic surfaces, and a robust pectoral region—lend support to interpretations that it engaged in aerial behavior more complex than passive gliding. That said, its flight would not have been elegant: drag and stability issues likely imposed serious constraints.

2. Changyuraptor

Changyuraptor, described in 2014, represents a larger and more heavily feathered version of the microraptorine lineage. The single known specimen, Changyuraptor yangi, measured about 1.2 m in length (including tail) and is considered the largest four-winged dinosaur currently known. Its forelimbs and hindlimbs both sport long flight feathers, echoing the multi-wing plan seen in Microraptor.

Where Changyuraptor becomes especially interesting is in the tail feathers: the distal fan is extremely long (around 30 % of the skeletal length), which may have helped control pitch and enable gentler landings or finer aerial maneuvering. Its heavier body compared to Microraptor raises questions about whether it could truly fly or only glide; but it certainly expands the known size limits of feathered, gliding dinosaurs.

3. Yi (Yi qi)

Yi (specifically Yi qi) is a unique and strange gliding dinosaur from the Jurassic of China, belonging to the scansoriopterygid clade. Unlike the feather-winged structures of Microraptor and Changyuraptor, Yi had a membranous gliding apparatus akin to a bat or flying squirrel. It sported an elongated “styliform” (rodlike) bone extending from the wrist to support the skin membrane.

Because Yi qi lacks strong muscle attachment sites for powerful flapping (its deltopectoral crest is small), most researchers infer it was primarily a glider rather than a flier. Its wing area and estimated wing‐loading fall within ranges compatible with gliding behavior, but the stability and control of its glides remain debated.

4. Anchiornis

Anchiornis, a small paravian from the Jurassic of China, is often viewed as a transitional form close to the bird line. It possessed relatively long forelimbs (about 80 % the length of its hindlimbs) and more bird-like wrists, suggesting a capacity for aerial locomotion.

However, detailed aerodynamic modeling indicates that adult Anchiornis specimens may have been too heavy relative to their wing area for effective flight. Juveniles might have used their wings to assist in running uphill or leaping (wing-assisted incline running), but full powered flight seems unlikely. The wings likely provided modest aerodynamic benefit, improving leaps or glides over short gaps rather than long flights.

5. Sinornithosaurus

Sinornithosaurus is a feathered dromaeosaurid from the Early Cretaceous Yixian Formation in China. Its fossilized feathers are fairly birdlike, with long arm feathers and contour plumage covering much of the body. Some researchers have proposed that Sinornithosaurus might have been able to glide or even attempt incipient flight, given its anatomical proximity to flying paravians.

The counterargument is that its size and limb proportions may have limited its aerodynamic efficiency. Some studies suggest it was too heavy or lacked sufficient wing area to sustain gliding over meaningful distances. Therefore, Sinornithosaurus likely represents a form on the margins—having feathers and perhaps occasional aerial capability, though not a robust flyer.

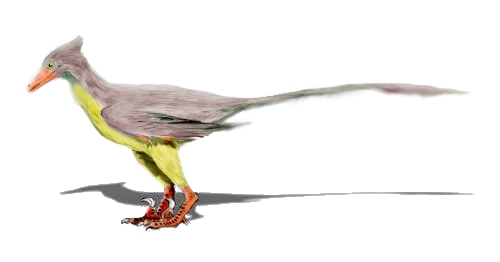

6. Rahonavis

Rahonavis is a small theropod from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar, often regarded as a bird-like dromaeosaur or early avialan. It has long arms fitted with evidence of quill knobs (attachment points for strong feathers), a characteristic associated with powered flight in birds. Because of these features, some paleontologists argue Rahonavis was capable of powered flight, albeit imperfectly. It might have been a clumsy flier, perhaps limited to bursts of flapping rather than sustained aerial behavior.

Others interpret it more cautiously, seeing it as a borderline flyer that may have combined gliding and wing-assisted running. These six taxa illustrate how diverse and experimental dinosaurian aerial locomotion was. From membrane-winged gliders to feathered four-winged forms, nature explored multiple strategies before modern birds perfected powered flight. Some species leaned more on gliding, while others flirted with true flapping flight. Many likely inhabited forested niches, launching from tree canopies or leaping between branches. As new fossils emerge and biomechanical models grow more sophisticated, our understanding of dinosaur flight will continue to evolve. These aerial pioneers sit at the crossroads of biology, physics, and evolution—challenging us to imagine life between branches and sky.