Picture this: you’re face-to-face with a pack of Velociraptors, their razor-sharp claws gleaming, their intelligent eyes calculating your every move. Hollywood has painted these creatures as the ultimate prehistoric killing machines, but what if everything you thought you knew about raptors was wrong? The truth about these fascinating predators is far more complex and surprising than any blockbuster movie could capture.

The Size Reality Check That Changes Everything

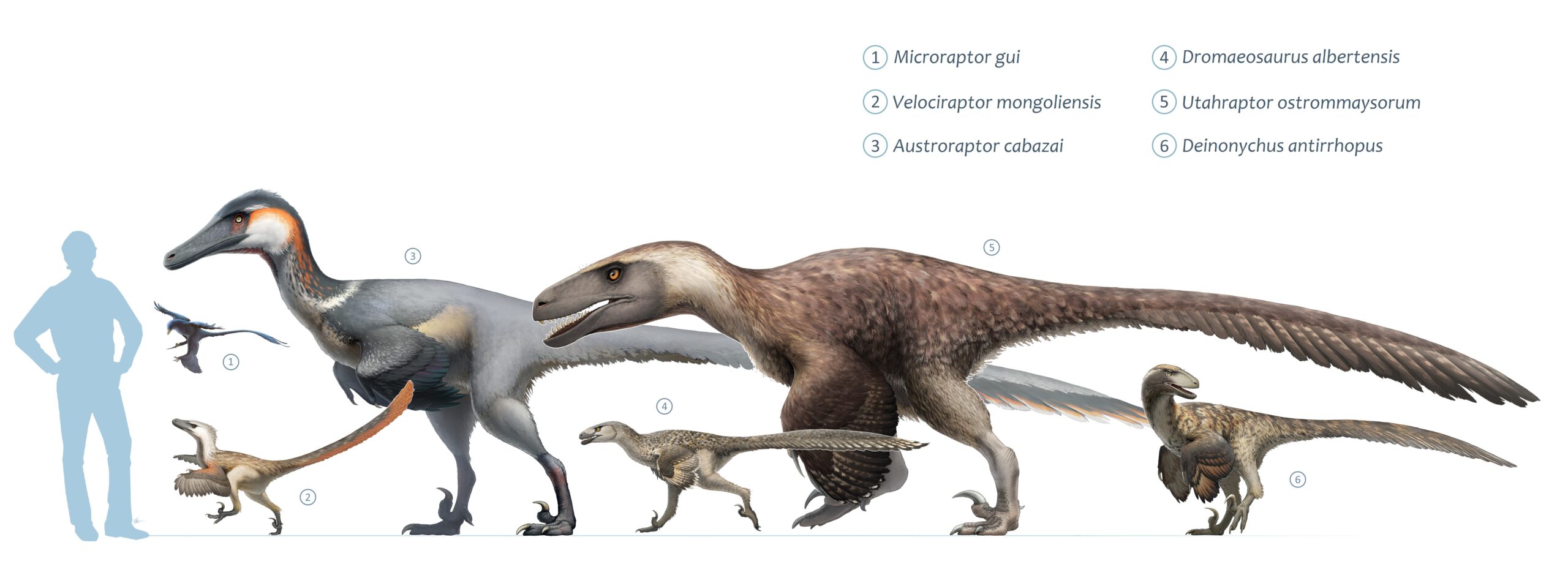

Most people envision raptors as human-sized monsters stalking through ancient forests, but the reality is quite different. The famous Velociraptor mongoliensis was actually about the size of a large turkey, standing roughly 1.6 feet tall and weighing around 33 pounds. This puts them closer to the size of a medium dog than the towering beasts we see on screen.

When you compare this to true apex predators of their time, the size difference becomes staggering. Tyrannosaurus rex could reach lengths of 40 feet and weigh up to 9 tons, making even the largest raptors look like snacks rather than competitors. The smaller dromaeosaurids would have been more concerned with avoiding becoming prey themselves than dominating their ecosystems.

Competition From True Giants Was Fierce

During the height of raptor evolution, the prehistoric world was dominated by creatures that made modern predators look tame. Massive theropods like Giganotosaurus and Carcharodontosaurus ruled the landscape with bone-crushing jaws and tremendous size advantages. These apex predators could easily dispatch any raptor foolish enough to challenge them.

The marine environments were equally hostile, with colossal predators like Mosasaurus and Megalodon controlling the seas. Even the skies weren’t safe, as pterosaurs with wingspans exceeding 30 feet soared overhead. Raptors found themselves in a world where bigger, stronger, and more specialized predators occupied the top tiers of the food chain.

The Feather Factor That Reveals Their True Nature

Recent fossil discoveries have revolutionized our understanding of raptor appearance and behavior. Many species, including Velociraptors andmicroraptorsr, possessed extensive feathering that served multiple purposes beyond simple insulation. These feathers were often colorful and elaborate, suggesting that raptors spent considerable time on display behaviors rather than pure predation.

The presence of flight feathers on some species indicates that certain raptors were more focused on aerial maneuvers than ground-based hunting. This feathered anatomy suggests they were transitional creatures, caught between the worlds of dinosaurs and birds. Their energy was divided between hunting, flying, and complex social behaviors that limited their effectiveness as single-minded predators.

Pack Hunting Myths Versus Scientific Evidence

Hollywood loves to portray raptors as coordinated pack hunters, working together with military precision to take down large prey. However, the fossil evidence tells a different story about their social behaviors. Most raptor fossils are found individually, and there’s limited evidence of the sophisticated pack coordination that would be necessary for apex predation.

The few instances where multiple raptor fossils are found together often suggest scavenging behavior rather than coordinated hunting. Modern birds of prey, which are raptors’ closest living relatives, are typically solitary hunters or form loose aggregations around abundant food sources. The complex social structures needed for effective pack hunting against large prey would require brain development that exceeds what we see in raptor fossils.

Dietary Habits That Weren’t So Fearsome

Analysis of raptor teeth, claws, and digestive systems reveals a more opportunistic diet than previously assumed. Many species show adaptations for eating fish, small mammals, and even plant material alongside their carnivorous tendencies. Their relatively small size meant they couldn’t tackle the massive herbivores that dominated their ecosystems.

Coprolites (fossilized feces) from raptor species often contain fish scales, small bones, and occasionally seeds or other plant matter. This suggests they were more like modern corvids or smaller birds of prey, taking whatever food sources were available rather than specializing in large-game hunting. Their survival strategy was flexibility, not dominance.

The Claw Controversy That Shook Paleontology

The infamous sickle claw that made raptors famous might not have been the devastating weapon we imagined. Recent biomechanical studies suggest these claws were better suited for climbing and grasping rather than slashing through thick hide and muscle. The angle and structure of the claw indicate it was designed for precision rather than brute force.

Comparisons with modern birds reveal that similar claws are used primarily for climbing trees, manipulating objects, and maintaining grip on prey or perches. The raptor’s sickle claw was likely used to climb trees, grasp branches, and hold onto smaller prey items. This versatile tool was more about survival and adaptation than creating the massive wounds depicted in popular media.

Brain Size and Intelligence Limitations

While raptors were indeed intelligent for their time, their brain-to-body ratio doesn’t support the cunning genius portrayal we often see. Their cognitive abilities were likely comparable to modern birds, which, while impressive, wouldn’t have given them the strategic advantages needed to dominate ecosystems filled with larger predators.

The fossil evidence suggests their intelligence was specialized for specific tasks like spatial navigation, prey tracking, and social communication within the species. However, this cognitive power was limited by their small brain size and would have been insufficient for the complex problem-solving needed to consistently outcompete larger, more physically imposing predators.

Environmental Pressures That Kept Them in Check

The ecosystems where raptors lived were incredibly competitive, with numerous predator species vying for the same resources. Climate changes, volcanic activity, and shifting sea levels created constant environmental pressures that prevented any single predator group from achieving total dominance. Raptors had to adapt to these changing conditions rather than simply overpowering their competition.

Food webs during the Mesozoic Era were complex networks where raptors occupied important but intermediate positions. They faced predation pressure from above while competing with other medium-sized predators for similar prey. This constant pressure from multiple directions meant they could never achieve the unchallenged dominance that true apex predators require.

The Scavenger Side of Raptor Life

Evidence increasingly suggests that many raptor species were opportunistic scavengers as much as active hunters. Tooth marks on bones and the positioning of fossils indicate that raptors often fed on carcasses left by larger predators. This scavenging behavior would have been a crucial survival strategy in competitive environments.

Modern ecosystems show us that successful predators often combine hunting and scavenging, but scavenging typically indicates a secondary role in the food chain. Raptors likely followed larger predators, waiting for opportunities to feed on leftovers or steal kills from smaller competitors. This behavior pattern suggests they were more like prehistoric vultures than apex predators.

Fossil Evidence That Contradicts the Killer Image

The fossil record provides compelling evidence that raptors weren’t the dominant predators of their time. Bite marks on raptor bones from larger predators, the rarity of raptor fossils compared to other theropods, and the contexts in which they’re found all point to a more vulnerable existence than popular culture suggests.

Many raptor fossils show signs of injury, disease, or malnutrition, indicating that survival was often a struggle. The famous “Fighting Dinosaurs” fossil from Mongolia shows a Velociraptor locked in combat with a Protoceratops, but both animals died in the encounter. This suggests that even successful hunts could be deadly affairs for raptors, hardly the mark of an apex predator.

Modern Analogies That Put Things in Perspective

To understand raptors’ true ecological role, consider modern predators like coyotes or jackals. These animals are intelligent, adaptable, and successful, but they’re not apex predators. They fill important ecological niches without dominating their environments, much like raptors did millions of years ago.

Raptors were probably more like prehistoric versions of these mesopredators, filling the crucial role of controlling smaller prey populations while avoiding direct competition with the true giants of their time. Their success came from adaptability and intelligence rather than raw power, making them important but not dominant members of their ecosystems.

The Hollywood Effect on Scientific Understanding

Movies and television have created a distorted image of raptor capabilities that’s influenced public perception for decades. The need for dramatic storytelling has overshadowed scientific accuracy, leading to widespread misconceptions about these creatures’ actual size, behavior, and ecological role.

This entertainment-driven portrayal has even influenced some scientific discussions, with researchers sometimes having to explicitly address movie-inspired myths in their papers. The real raptors were fascinating creatures with complex behaviors and important ecological roles, but they weren’t the unstoppable killing machines that Hollywood created.

What Raptors Excelled At

Despite not being apex predators, raptors were remarkably successful at what they did. Their combination of intelligence, agility, and adaptability made them excellent at exploiting specific ecological niches. They were skilled climbers, efficient hunters of small to medium prey, and showed remarkable diversity in their feeding strategies.

Their evolutionary success is evident in their widespread distribution and eventual transition into modern birds. Rather than being failed apex predators, raptors were highly successful mesopredators who played crucial roles in their ecosystems. Their legacy lives on in every bird that soars through our skies today, proving that success in evolution doesn’t always mean being the biggest or fiercest.

Conclusion

The truth about raptors is more fascinating than fiction. These creatures navigated complex prehistoric worlds using intelligence, adaptability, and specialized skills rather than brute force. They weren’t the apex predators Hollywood portrayed, but they were something perhaps more remarkable: survivors who found their perfect niche in a world full of giants. Their story reminds us that in nature, the most successful aren’t always the strongest, but often the most adaptable.