Have you ever imagined what it would be like to stroll through your neighborhood and come face to face with a creature the size of an elephant covered in shaggy fur? Picture towering beasts with claws longer than kitchen knives, or wolves far larger and fiercer than anything prowling today’s wilderness. Not that long ago – really, just a blink in geological time – these colossal animals roamed the very ground you walk on now.

North America was home to these magnificent giants until around 10,000 years ago when they mysteriously disappeared. This continent once rivaled Africa’s plains for sheer diversity of massive wildlife. Yet most of us know surprisingly little about these incredible creatures that shaped the landscape and ecosystems our ancestors witnessed firsthand. The story of their existence and vanishing remains one of paleontology’s most captivating mysteries, filled with revelations that continue to emerge from ancient bones and fossilized clues.

Let me take you on a journey back to when North America was truly wild.

They Were Far More Diverse Than You’d Expect

Here’s something that might blow your mind. During the Late Pleistocene, about 72% of all megafaunal species in North America became extinct – and that tells us just how incredibly diverse this lost world really was. We’re not just talking about a handful of big animals here and there.

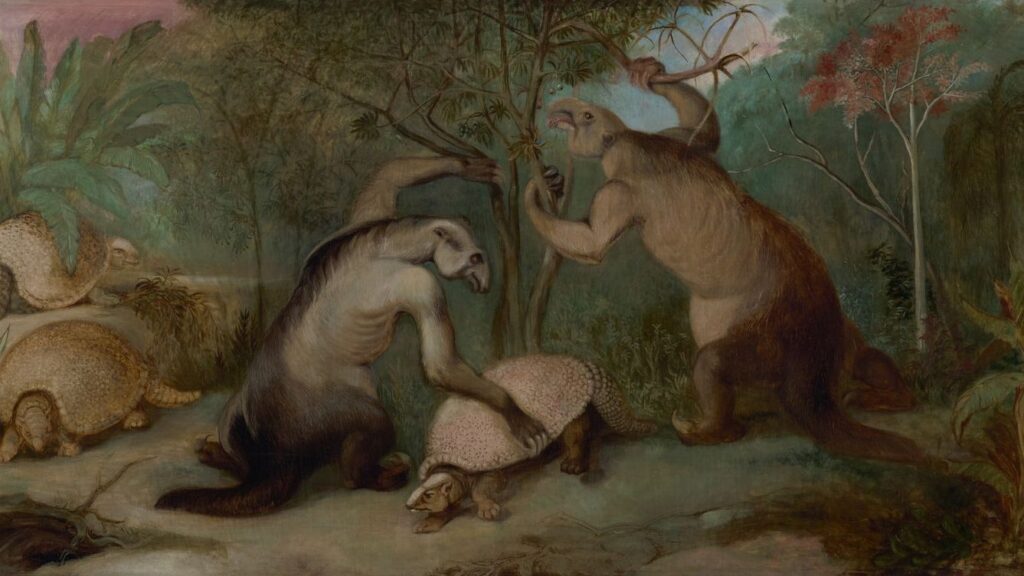

At the end of the Pleistocene in North America, 38 genera of mammals vanished, and these weren’t all closely related creatures. Think about the variety: there were enormous armadillo-like glyptodonts, several species of giant ground sloths ranging from bear-sized to truly massive, multiple types of elephantine creatures, huge bears, big cats with terrifying teeth, enormous wolves, and even American camels and horses. Before this extinction, the diversity of large mammals in North America was similar to that of modern Africa. That means the Great Plains once rivaled the Serengeti for spectacular wildlife viewing, if only humans had been around with cameras instead of spears.

The Dire Wolf Wasn’t Really a Wolf at All

If you’re a Game of Thrones fan, this one’s going to mess with your head. The dire wolf, that legendary predator we thought we understood, turned out to be something completely different from what scientists believed for over a century.

Genetic analysis revealed that dire wolves occupy their own lineage, separate from those that gave rise to gray wolves, coyotes, and dogs by nearly 6 million years. Let me put that into perspective – they were so distantly related to actual wolves that calling them wolves is almost misleading. They probably evolved in the Americas where they were the only wolflike species for hundreds of thousands of years, and when gray wolves arrived from Eurasia, dire wolves were apparently unable to breed with them. They lived among these newcomers but remained genetically isolated, like strangers in their own land. Living in warmer latitudes may have given them traits like red fur, a bushy tail, and rounded ears – so they may have looked like a giant, reddish coyote rather than the gray, bulky timber wolf we always imagined.

Giant Ground Sloths Could Stand Taller Than a Basketball Hoop

Forget everything you think you know about sloths from watching nature documentaries. Those cute, slow-moving tree dwellers you’ve seen? They’re nothing like their prehistoric relatives.

The giant ground sloths of the late Pleistocene were bear-sized herbivores that stood 12 feet on their hind legs and weighed up to 3,000 pounds. To visualize this properly, that’s taller than most residential ceilings. Megatherium was up to 10 times the size of living sloths, reaching weights of up to four tonnes, and on its hind legs would have stood a full 3.5 metres tall. Honestly, it’s hard to say for sure, but encountering one of these creatures standing upright would have been absolutely terrifying – even though they were vegetarians.

One species, the Jefferson ground sloth, was named for Thomas Jefferson, who initially believed sloth fossils were a type of colossal cat he dubbed the Megalonyx. The founding father got it spectacularly wrong at first, which just shows how bizarre these creatures were.

Saber-Toothed Cats and Dire Wolves Weren’t Competing for the Same Prey

For decades, scientists assumed these two iconic predators were bitter rivals fighting over the same food sources. Turns out, they had things figured out pretty well without stepping on each other’s toes.

Stable isotopes in saber-toothed cat teeth suggest they were feeding on animals like camels, tapir and deer in forested environments, while dire wolves were likely running down horses and other large grazing mammals in open areas. It’s actually quite clever when you think about it – nature had already worked out a system where these apex predators divided up the landscape and prey. The cats and dogs partition out what they are doing, as one researcher put it simply.

This discovery completely changes our understanding of why they went extinct. Previously, some experts thought competition between these predators might have contributed to their demise. Now we know they weren’t really competing at all, which makes their simultaneous disappearance even more mysterious.

Mastodons and Mammoths Were More Different Than You Think

Most people use these names interchangeably, assuming they’re basically the same animal with slightly different features. That’s like saying a grizzly bear and a raccoon are basically the same because they’re both furry mammals.

Mammoths are more closely related to modern elephants, separated by merely 5 million years of evolution, while mastodons are much more distantly related, separated by about 25 million years. That’s a massive evolutionary gulf. Their teeth tell an even more interesting story. Mastodons were wood browsers and their molars have pointed cones specially adapted for eating woody browse, while mammoths had ridged teeth perfect for grinding grasses.

Fully-grown male Columbian mammoths weighed nearly 10 tons and stood about 13 feet tall, while male American mastodons reached heights of 10 feet and weighed in around 6 tons. They lived in different habitats, ate different food, and probably rarely encountered each other. These weren’t cousins sharing the same ecological niche – they were distant relatives who’d figured out how to coexist by staying out of each other’s way.

The Short-Faced Bear Was an Absolutely Terrifying Running Machine

Let’s be real – if you think modern bears are scary, you haven’t met Arctodus simus. This thing was the stuff of nightmares, and not just because of its size.

The giant short-faced bear was the largest carnivorous mammal to ever roam North America, and standing on its hind legs, an adult boasted a vertical reach of more than 14 feet. That’s roughly the height of a single-story building. Here’s where it gets really unsettling: The most striking difference between modern bears and the giant short-faced bear were its long, lean and muscular legs, which has given rise to the idea that it was a cursorial predator, meaning it ran after prey.

Most modern bears lumber along at decent speeds but tire relatively quickly. This prehistoric monster was built differently – those long legs suggest it could actually chase down prey across long distances on the open plains. Imagine being hunted by something that size with that kind of endurance. It’s no wonder smaller predators and prey animals had to be constantly on alert.

Humans Witnessed Their Final Days and May Have Sealed Their Fate

This is where things get uncomfortable and controversial. Around 12,700 years ago, North America lost 70 percent of its large mammals, and the timing is suspiciously coincident with human expansion across the continent.

When humans colonized these continents, they decimated animals that were unused to being hunted, and there is archaeological evidence to support this hypothesis, with the fact that extinctions followed first contact by humans being consistent with it. However, the story isn’t quite that simple. Between 75% and 90% of the northeastern megafauna were gone before humans ever came on the scene, suggesting climate change played a significant role. The timing of massive wildfires coincides with both a growing human population and the demise of megafauna, pointing to a complex interaction between human activity and environmental change.

The truth is probably somewhere in the messy middle – a perfect storm of rapid climate change, shifting vegetation, and a new predator (us) that these magnificent creatures simply couldn’t adapt to quickly enough. Megatherium fossils have been dated as young as 8,000 to 7,000 years ago, and there’s evidence of humans hunting these giant ground sloths. These animals didn’t just disappear into the mists of time – they vanished while humans were watching.

Conclusion

The prehistoric giants of North America left behind more than just scattered bones and museum displays. They shaped the very landscape we inhabit today, from the forests they browsed to the grasslands they maintained. Their disappearance fundamentally changed the continent’s ecosystems in ways we’re still discovering.

What’s perhaps most haunting is how recently they walked this earth. Ten thousand years might sound like ancient history, but in geological terms it’s practically yesterday. These weren’t distant dinosaurs from 65 million years ago – these were creatures that our ancestors knew, hunted, feared, and possibly drove to extinction. Every time you walk through a forest or across a meadow in North America, you’re traversing ground that once trembled under the footsteps of bears taller than buildings and sloths the size of small cars. Their absence is a reminder of how quickly we can lose the irreplaceable, and how dramatically humans can alter the natural world around them.

What do you think – could climate change alone have wiped them out, or did our ancestors play the deciding role? The debate continues, and new discoveries keep reshaping our understanding of these forgotten giants.