The deep past of Earth is strewn with tantalizing fossils — skeleton fragments, bones, vertebrae, bits of hips and limbs — that defy tidy categorization. Over the last century, paleontologists have built tree after tree of dinosaur interrelationships (phylogenies), yet some taxa stubbornly resist placement. These “enigmatic dinosaurs” fall into the category incertae sedis (of uncertain placement), because the evidence is ambiguous, fragmentary, or conflicting.

In this article we explore eight dinosaur (or near-dinosaur) taxa that continue to puzzle scientists. Each carries a mix of bizarre traits, missing bones, or conflicting signals — not yet enough consensus to firmly nest them in known groups. Their mysteries hint at how much we still have to learn about dinosaur evolution and the branching of their family tree.

1. Chilesaurus

Chilesaurus, discovered in Late Jurassic sediments in Chile, is among the most strikingly ambiguous dinosaurs. Though originally described as a theropod, it exhibits features that seem borrowed from herbivorous ornithischians and even basal sauropodomorphs (for example, spatulate teeth and certain hip features). This mosaic of traits has led different authors to place it in separate major dinosaur lineages.

In 2017, Baron & Barrett proposed that Chilesaurus might actually be a basal ornithischian, reshuffling the traditional dichotomy between saurischians and ornithischians

Others continue to favor a theropod position or even suggest it’s a basal tetanuran close to the theropod stem. Because its skeleton is relatively well known, its ambiguous position underscores how even well-preserved forms can confound phylogenetic analyses when they straddle boundaries.

2. Zuolong

Zuolong, from Late Jurassic deposits in China, is another taxon whose classification shifts depending on the analysis. Different phylogenetic studies have placed it in varying positions among coelurosaurian or basal tetanuran theropods

Part of the tension arises because Zuolong exhibits a mix of primitive and derived characters. Some analyses place it just outside major derived theropod clades, while others nest it closer to coelurosaurs. The shifting placements reflect both the fragmentary nature of some

3. Imperobator

Imperobator is known from Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) fossils recovered in Antarctica. Because fossils of theropods from that region and time are rare, its affinities are especially uncertain

When first described, Imperobator was tentatively assigned as a dromaeosaur (a “raptor” dinosaur), but the specimen lacks a prominent “sickle claw” typical of classic dromaeosaurids. Later work placed it more generally in Paraves (the broader group containing birds, dromaeosaurs, and troodontids) in an uncertain position

Some recent analyses have even suggested affinities with unenlagiine clades, though consensus remains elusive

4. Gualicho

Gualicho is a mid-sized theropod from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia. Its skeleton is incomplete (in particular, the skull is missing), which complicates efforts to classify it rigorously. Because its preserved elements combine traits seen in megaraptorans, carcharodontosaurians, and coelurosaurs, different analyses have placed Gualicho in diverging parts of the theropod tree. Some favor treating it as a megaraptoran within Carcharodontosauria, whereas others argue for a closer relationship to coelurosaurian groups — yet the evidence is not definitive enough to settle the dispute

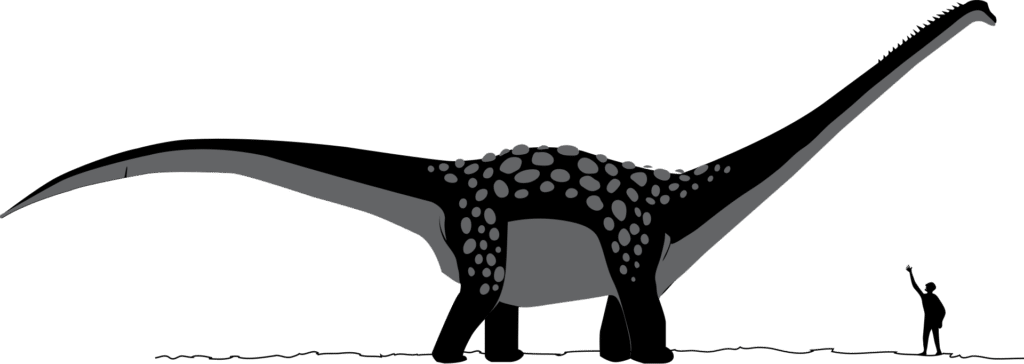

5. Brohisaurus

Brohisaurus is a dubious Late Jurassic genus from what is now Pakistan. The known fossil material comprises largely fragmentary ribs, vertebrae, and limb bones — not enough to diagnose distinguishing synapomorphies (shared derived traits) unambiguously

Though originally described as a titanosaur (a branch of sauropods), none of its traits firmly tie it to that group. Some features are tentatively reminiscent of titanosauriforms, but these are not definitive, leaving its precise affinities open to question

6. Janenschia (robusta)

Janenschia robusta is a large-bodied dinosaur from the Tendaguru Beds (Late Jurassic, Tanzania). Though often called a sauropod, its true relationships are shaky because its holotype is based on a very incomplete hindlimb — making it difficult to connect additional material with confidence

Over time, portions of the tail previously assigned to Janenschia have been reinterpreted and sometimes removed to separate genera, because they don’t clearly match diagnostic features of the holotype material

Some analyses even find affinities to Camarasaurus or other non-titanosaur branches, rather than firmly within derived sauropod clades

7. Dandakosaurus

Dandakosaurus is an Early Jurassic genus from the Kota Formation in India, described based on a partial proximal pubis bone. Because the holotype is so limited — essentially just one bone — many paleontologists consider it a nomen dubium (dubious name)

With so little to work on, assigning Dandakosaurus to any specific theropod group remains speculative. It has been variously placed as a megalosauroid or indeterminate carnosaur, but none of these positions is well supported.

8. “Antarctosaurus” (various species)

While Antarctosaurus is usually listed among titanosaurs, the genus suffers from serious taxonomic confusion. Much of the material assigned to Antarctosaurus comes from disparate and fragmentary bones whose association is uncertain

Certain named species within the genus have been reinterpreted or deemed dubious; many lack clear diagnostic characters that differentiate them from other titanosaurs. As a result, paleontologists often treat some “Antarctosaurus” species as nomina dubia or reassign them to new genera when better material emerges

These eight taxa illustrate both the promise and challenge of paleontology. Even as we discover more fossils, anatomical mosaics, missing parts, and analytical sensitivity often thwart tidy classification. Some taxa may someday fall neatly into established groups when new fossils turn up; others may require rethinking of major relationships (or the creation of new clades). The continued study of such enigmatic dinosaurs reminds us that the tree of life — especially among extinct giants — is a work in progress, and many branches remain shrouded in mystery.