Picture this: you’re standing on a windswept plain 15,000 years ago. The air is cold, the grass is tall, and somewhere in the distance, a sound echoes that would make your blood run cold. These weren’t the predators you see in modern zoos. The creatures that stalked Ice Age America were bigger, stranger, and far more cunning than most people realize.

The truth is, we’ve been getting the story wrong for decades. Sure, you’ve heard about saber-toothed cats and dire wolves, but what you probably don’t know is how these ancient hunters actually lived, fed, and survived in one of the most competitive ecosystems Earth has ever seen. Their behaviors weren’t just brutal – they were surprisingly complex, sometimes cooperative, and often downright bizarre. Let’s dive into the hidden world of prehistoric American predators and uncover behaviors that will completely change how you see these Ice Age giants.

They Cared for Their Wounded Packmates

Evidence of healed injuries in fossil specimens suggests these fearsome predators may have cared for injured pack members, hinting at complex social behaviors. Think about that for a moment. More than 5,000 of the Smilodon bones at La Brea have marks of injury or illness: tooth decay, heavily worn arthritic joints, broken legs and dislocated elbows, while dramatic examples include crushed chests and spinal injuries, which the cats somehow survived.

How does a saber-toothed cat with a crushed chest continue living? It doesn’t, unless others are bringing it food. Some of these injuries were so severe that survival would have been impossible without help from the pack. This changes everything we thought we knew about these supposedly solitary hunters. They weren’t just killing machines – they were looking out for each other.

Dire Wolves Weren’t Actually Wolves at All

Here’s something that’ll blow your mind. A new study of dire wolf genetics has startled paleontologists: it found that these animals were not wolves at all, but rather the last of a dog lineage that evolved in North America. For over 150 years, scientists assumed dire wolves were just supersized versions of modern gray wolves. Wrong.

Emerging genetic data on several dire wolf specimens suggest that, surprisingly, they were not closely related to gray wolves, but had a closer relationship to today’s jackals, with these data suggesting that dire wolves descended from a carnivore lineage going back 5 million years ago in North America. This means every time you’ve imagined a dire wolf howling like a modern wolf, you’ve probably been picturing the wrong sound entirely. Their vocalizations, their pack dynamics, even their appearance might have been vastly different from what we’ve always assumed.

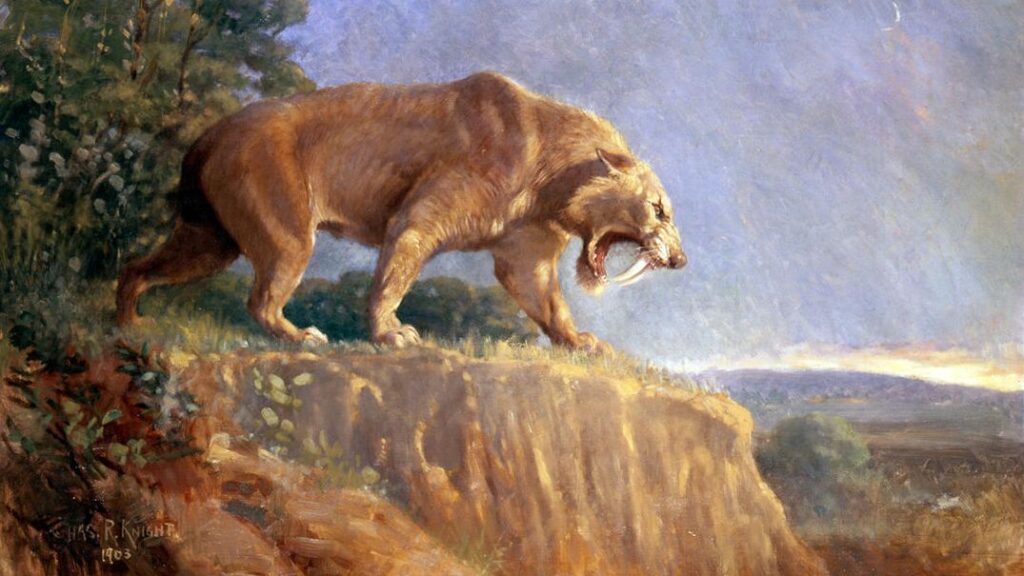

Saber-Toothed Cats Hunted in Forests, Not Open Plains

According to analysis of their teeth, the saber-tooth cats of the American West were most likely forest-dwellers that hunted animals such as tapir and deer. This goes against decades of popular imagery showing these cats prowling grasslands like African lions. The truth is far more interesting.

Recent tooth enamel analysis has completely rewritten the saber-tooth playbook. When we look at the enamel, we get a totally different picture, finding that the saber-tooth cats, American lions, and cougars are actually doing what cats typically do, which is hunting within forested ecosystems. They were ambush predators who used tree cover to their advantage. Picture them crouched in dappled shadows, those massive canines ready to strike from the undergrowth. That’s a far cry from the open-savanna hunters we’ve always imagined.

Short-Faced Bears Used Their Noses to Steal Meals

The giant short-faced bear had a superpower that made it one of the most successful predators of its time, even though it might not have been much of a hunter at all. The nasal opening is very large, suggesting they had a pronounced sense of smell, which combined with their long limbs, point to the short-faced bear as a solitary, wide-ranging scavenger of carcasses, as the short-faced bear would probably smell the scent of meat in the wind, follow it to the carcass, chase off the lions or wolves, and dine on the leftovers.

Imagine being a pack of dire wolves that just spent hours taking down a bison, only to smell a seven-foot-tall bear charging toward you at speeds of nearly 40 mph. You’d run too. The chemistry of short-faced bear fossil bones from Yukon and Alaska indicate a diet nearly completely composed of meat. They were basically the bullies of the Ice Age, using size and speed to take what others had worked hard to kill.

American Lions May Have Hunted in Prides Like Modern Lions

Much like in modern lions the American lion likely lived in prides and performed cooperative hunting, with evidence of prides and group hunting in the American lion difficult to come by, though disproportionately high mortality in young males at La Brea Tar Pits has been observed, which would make sense as young males are expelled from lion prides in Africa. This behavioral pattern mirrors what we see in African lions today.

The fossil record hints at something profound here. Young male American lions seem to have died more frequently, possibly because they were kicked out of their family groups and forced to fend for themselves – inexperienced, reckless, and vulnerable. The American Lion had one of the largest brains of any cat live or extinct which suggests that they were social like modern lions able to hunt together as a pride. A coordinated pride of cats that weighed up to 25 percent more than modern African lions? That’s a hunting force unlike anything alive today.

Dire Wolves Ate So Fast They Broke Their Teeth

Competition in Ice Age America was absolutely fierce. When there is low prey availability, the competition between carnivores increases, causing them to eat faster and thus consume more bone, leading to tooth breakage. Dire wolves faced such intense pressure from other predators that they literally didn’t have time to eat carefully.

The 15,000 YBP dire wolves had three times more tooth breakage than the 13,000 YBP dire wolves, and by 13,000 YBP, as the prey species moved towards extinction, predator competition had declined and therefore the frequency of tooth breakage in dire wolves had also declined. What this tells us is chilling: there was a period where the competition was so brutal that wolves were crunching through bones in a desperate race to consume as much as possible before competitors arrived. It’s a window into just how cutthroat survival was.

Pack Hunting Evolved Separately Multiple Times

The dorsoventrally weak symphyseal region of the dire wolf indicates that it delivered shallow bites similar to its modern relatives and was therefore a pack hunter. But here’s the fascinating part: dire wolves weren’t closely related to modern wolves, yet they independently evolved nearly identical pack-hunting strategies.

Like humans of the time, and wolves of today, they probably hunted in coordinated groups, separating weaker prey from their herds before jumping in for the kill. This is convergent evolution at its finest. Completely different lineages, separated by millions of years, arrived at the same solution: work together or die alone. It speaks to just how effective cooperative hunting was in taking down the massive herbivores of the Pleistocene.

Saber-Tooth Canines Were Fragile Precision Instruments

You’d think those iconic seven-inch fangs were brutally tough weapons, right? Actually, the opposite is true. Its immense upper canine teeth, up to 20 cm long, were probably used for stabbing and slashing attacks, possibly on large herbivores such as the mastodon, with its skull modified to accommodate the attachment of strong neck muscles for bringing the head down.

Even though their canines were massive and intimidating, their jaws weren’t strong enough to bite through bones. These cats had to use their teeth like surgical knives, precisely targeting soft tissue areas like the throat and abdomen. One wrong move – hitting bone or struggling prey thrashing at the wrong angle – and those teeth could snap. It required incredible skill and probably explained why pack behavior was so important: other cats could help hold prey still while the killing bite was delivered.

They Fell Victim to the Tar Pits in Droves Because They Couldn’t Resist Easy Prey

What may have happened is that prey animals ventured into the tar seeps, became entangled and started thrashing about because they were unable to extricate themselves, which in turn lured the wolves to make the same mistake, in pursuit of easy prey. La Brea wasn’t just a trap – it was an irresistible lure for hungry predators.

Fossils of dire wolves and saber-toothed cats together outnumber herbivores about 9-to-1 at La Brea, leading scientists to speculate that both predators may have formed prides or packs, yet a small number of experts argue against cooperative behavior for Smilodon, reasoning that pack-living animals would have been too intelligent to get mired en masse. Here’s the thing: even smart predators make mistakes when they’re starving. The tar pits captured thousands of these animals precisely because desperation overrode caution. It’s a sobering reminder that survival in that world was always on a knife’s edge.

Conclusion

The prehistoric predators of Ice Age America were far more than the one-dimensional monsters popular culture has painted them to be. They showed compassion, adaptability, and cunning. They faced challenges we can barely imagine – competition so fierce they shattered their own teeth, prey so massive it required coordinated teamwork, and an ecosystem so unforgiving that one wrong step into a tar pit meant death.

These behaviors reveal creatures that were complex, intelligent, and surprisingly relatable. They cared for their injured. They worked together. They adapted to their environments with remarkable precision. Understanding these ancient hunters isn’t just about learning cool facts – it’s about recognizing that the natural world has always been more intricate and fascinating than we give it credit for. What other secrets are still buried out there, waiting to be discovered? Which of these behaviors surprised you the most?