Have you ever imagined dinosaurs as social creatures, organizing their lives in complex communities? The truth is, these ancient giants were far more sophisticated than most of us realize. Long before humans walked the Earth, dinosaurs formed intricate social structures that rivaled today’s most intelligent animals. From caring parents to strategic herds, the prehistoric world was alive with cooperation and communication. Let me take you through some astonishing discoveries that are completely reshaping how we think about these remarkable creatures.

They Lived in Herds Nearly 200 Million Years Ago

Researchers discovered an exceptionally preserved group of early dinosaurs that shows signs of complex herd behavior as early as 193 million years ago, pushing back previous records by a staggering 40 million years. Since 2013, teams have excavated more than 100 dinosaur eggs and the partial skeletons of 80 juvenile and adult dinosaurs from a rich fossil bed in southern Patagonia. These remains belonged to Mussaurus patagonicus, a plant-eating dinosaur that lived during the early Jurassic period.

What makes this discovery mind-blowing is the timing. Honestly, scientists had no idea that such sophisticated social behavior existed so early in dinosaur evolution. Adults shared and took part in raising the whole community, suggesting a larger community structure rather than simple family units. This wasn’t just parents watching their own kids. It was an entire village raising the young together.

Age Segregation Was Common Practice

Perhaps one of the most intriguing behaviors scientists have uncovered is that dinosaurs separated themselves by age within their herds. Articulated skeletons were grouped in clusters of individuals of approximately the same age, much like how modern elephants or wildebeest organize themselves. Think about it: juveniles hung out together while adults formed their own groups, yet they all remained part of the same larger herd.

Evidence suggests that Mussaurus optimized foraging potentials during the early Jurassic via age-based social partitioning, with neonates, juveniles, and adults apparently foraging and even perishing in age-based groups. This wasn’t random. Different age groups had different needs, different speeds, and different vulnerabilities. Separating by age made perfect evolutionary sense for survival.

Colonial Nesting Sites Reveal Protective Communities

The fossils were found in several layers of sediment, suggesting that the dinosaurs returned to the site year after year to nest, a behavior ornithologists call nest site fidelity. The eggs were found in clutches of eight to 30, arranged carefully in common breeding grounds. These weren’t isolated parents hiding their eggs. These were communal nurseries where multiple families nested together for mutual protection.

The spacing tells its own story. Nests were spaced about seven metres apart, roughly one dinosaur length, suggesting they liked being close but not so close they’d bicker. It’s hard to say for sure, but this pattern resembles modern communally nesting birds. The repeated layers of nests in the same location indicate generations returning to trusted, favorable nesting sites year after year.

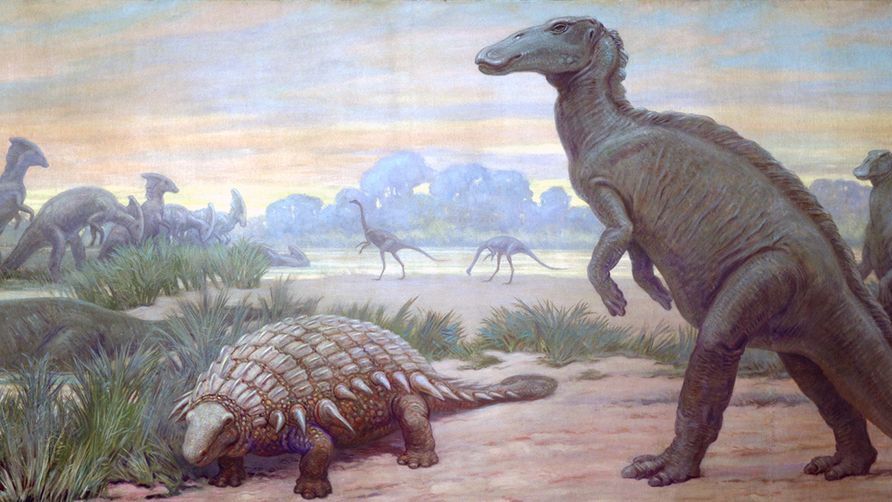

Mixed Species Herds Were Possible

Here’s where things get really wild. Footprints uncovered in the Canadian province of Alberta could be evidence that some dinosaurs moved in herds comprising multiple different species, with ceratopsians and ankylosaurids possibly walking together. This would have been similar to how modern wildebeest and zebras travel together across the African plains.

Let’s be real: this challenges everything we thought we knew about dinosaur social structures. Different species cooperating? That requires recognizing not just your own kind but also understanding the benefits of interspecies cooperation. Two large Tyrannosaurus rex trackways were also discovered walking side-by-side and perpendicular to the herd, suggesting these mixed herds might have been a defense strategy against common predators.

Parental Care Extended Far Beyond Hatching

Dinosaurs weren’t just egg-layers who abandoned their young. Fossil evidence suggests that Maiasaura parents nested in large colonies, creating a social structure similar to modern-day birds, providing extensive food and protection for their hatchlings. Juvenile dinosaur bones discovered in Montana indicate parental care and support during early life stages.

Some baby hadrosaurs had worn teeth before they could walk properly, strongly suggesting parents brought food directly to the nest. The nesting colonies indicate a social structure that involved multiple adults working together to raise the young, a level of cooperative care quite rare in the animal kingdom. Evidence suggests juveniles remained in or near the nesting colony until reaching about half their adult size, indicating extended parental or group care.

Trackways Reveal Sophisticated Group Movement

Fossil footprints provide some of the most compelling evidence of herding behavior. Trackways were first noted in the early 1940s along the Paluxy riverbed in central Texas, where numerous washbasin-size depressions proved to be a series of giant sauropod footsteps, with tracks nearly parallel and progressing in the same direction. Large trackway sites also exist in the eastern and western United States, Canada, Australia, England, Argentina, South Africa, and China, documenting herding as common behavior across the globe.

Some dinosaur trackways record hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of animals, possibly indicating mass migrations. Can you imagine the ground-shaking thunder of thousands of massive creatures moving together? Ten sauropod trackways on one bedding-plane surface recorded the herding movements of seven smaller sauropods (juveniles) and three larger ones (adults), all walking in the same direction.

Communication Through Elaborate Structures

Elaborate crests and frills, particularly in Hadrosaurs like Parasaurolophus, contained convoluted nasal passages that acted as resonating chambers for vocal communication. CT scans have confirmed these structures were used to produce low-frequency bellowing calls, likely for attracting mates or warning the herd. These dinosaurs weren’t silent giants lumbering through prehistoric landscapes. They were vocal, communicating across vast distances.

The frills of ceratopsians likely served multiple purposes beyond defense. While these frills might have served to protect the vulnerable neck from predators, they may also have been used for display, thermoregulation, or the attachment of large neck and chewing muscles, or some combination. Visual signals combined with vocal communication would have created rich social interactions within herds, allowing for coordination and warnings about approaching danger.

Herding Provided Evolutionary Advantages

Living in herds may have given Mussaurus and other social sauropodomorphs an evolutionary advantage, particularly since these early dinosaurs originated shortly before an extinction event wiped out many other animals. For whatever reason, sauropodomorphs held on and eventually dominated the terrestrial ecosystem in the early Jurassic.

The evolution of complex social behavior among sauropodomorphs may have coincided with increases in body size that occurred between 227 million and 208 million years ago, as meeting the increased energy requirements associated with larger body sizes may have required coordinating their behavior to forage over long distances. Living in herds might have allowed species to collectively find more food to fuel their large bodies, while also protecting vulnerable young from predation.

Social Behavior Varied Widely Between Species

Not all dinosaurs were equally social, and that diversity is absolutely fascinating. Members of each mass death assemblage likely had their own specific conditions driving them to form relatively small herds, indicating a more complex social structuring in ankylosaurs than previously acknowledged. Some, such as Alamosaurus, seemed to group together in small herds as juveniles and either become solitary as they grew or form age-segregated adult herds, while other sauropods lived in mixed-age herds where juveniles remained with older individuals.

Just like living animals exhibit a variety of behaviors from species to species, it’s likely that dinosaurs also were variable in their parenting, with some being neglectful and burying their eggs while others caringly tended to their nests. This variability reveals that dinosaur social behavior was just as nuanced and species-specific as we see in modern animals today.

The discoveries about dinosaur social behavior continue to revolutionize our understanding of these ancient creatures. They weren’t solitary monsters roaming isolated landscapes. They were sophisticated social animals with complex community structures, communication systems, and cooperative behaviors that helped them dominate Earth for millions of years. Evidence is piling up: dinosaurs were warm-blooded, feathered, fast-moving and had sophisticated behavior.

What surprises you most about how these prehistoric giants lived together? The idea that they communicated with elaborate calls, or that they cooperated across species boundaries? Share your thoughts in the comments below.