Ever find yourself stopping in the middle of a hike to inspect a particularly interesting rock? Or maybe you’ve spent hours down a Wikipedia rabbit hole learning about ancient ecosystems? You might be surprised to discover that these quirks aren’t just random interests. They’re clues to something deeper, a set of behaviors that mirror the way professional paleontologists experience the world.

Let’s be real, you don’t need a PhD to think like someone who studies ancient life. The traits that draw people to paleontology are often hiding in plain sight, woven into everyday habits that most folks wouldn’t think twice about. Whether you’re someone who approaches problems methodically or finds joy in piecing together incomplete information, these patterns say something fascinating about how your mind works.

You’re Obsessed With the Bigger Picture, Not Just the Details

Here’s the thing about paleontology: it’s not just about digging up bones. Paleontologists are inquisitive by nature, and they gather evidence of all kinds to test their hypotheses. If you’re someone who can’t help but zoom out and consider context, you’re already thinking like a fossil hunter. You see a small clue and immediately start connecting it to broader patterns, whether it’s understanding why your houseplants keep dying or figuring out what really happened in that confusing family story.

This habit goes beyond mere curiosity. The psychological profile of a paleontologist is characterized by a blend of curiosity, perseverance, analytical thinking, resilience, and creativity. These traits enable them to navigate the uncertainties and challenges inherent in uncovering Earth’s ancient past. You probably don’t settle for surface explanations. Instead, you dig deeper, literally and figuratively, searching for the underlying truth that explains why things are the way they are.

You Have Infinite Patience for Slow, Meticulous Work

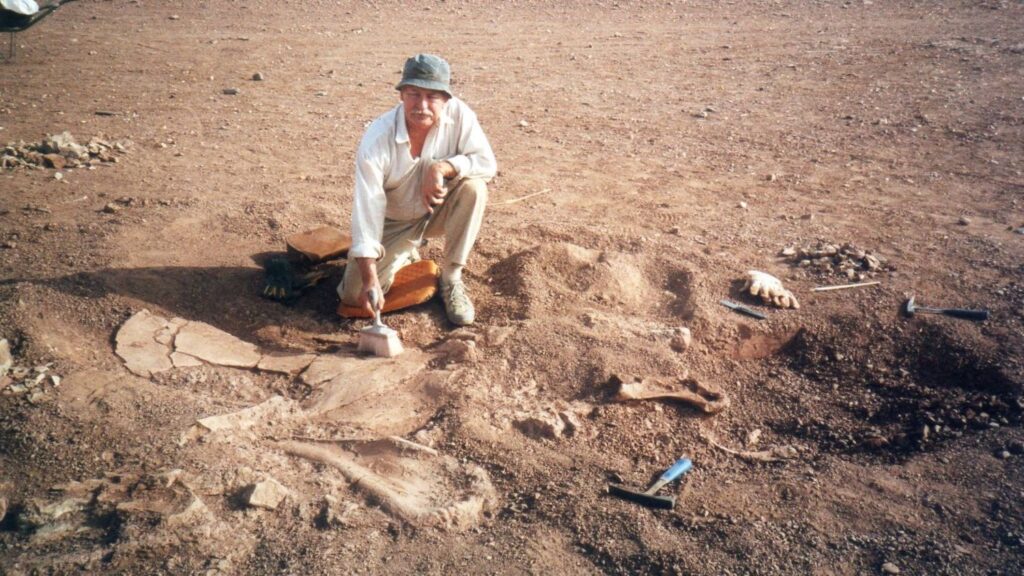

Think about it: professional paleontologists might spend years on a single research project. Many paleontologists establish structured routines for fieldwork, analysis, and writing, which help manage workload and reduce chaos-induced stress. If you’re the type who can spend an entire Saturday organizing your book collection by obscure criteria, or if you find satisfaction in tasks that require sustained attention over long periods, you’re channeling that same energy.

Most people get bored when progress feels glacial. You, though? You might actually enjoy the process of slow revelation. There’s something meditative about working through a complex puzzle piece by piece, whether you’re restoring an old piece of furniture or sorting through years of family photos. The journey matters as much as the destination, which is exactly how paleontologists approach important work that requires a lot of skill and patience.

You’re Comfortable With Uncertainty and Incomplete Information

Fossil records are inherently fragmentary. Paleontologists often work with incomplete specimens, requiring them to make educated guesses. Does this sound familiar? Maybe you’re the friend who can make decisions even when you don’t have all the facts. You’re skilled at working around gaps in knowledge, filling in blanks with logical inferences rather than getting paralyzed by what’s missing.

This ability to embrace the unknown is rarer than you’d think. While some people need absolute certainty before moving forward, you’ve learned to be comfortable in the gray areas. You understand that sometimes the best you can do is form a hypothesis based on limited evidence and adjust as new information emerges. It’s not about being reckless; it’s about being adaptable and resourceful when faced with life’s inevitable mysteries.

You See Patterns Where Others See Randomness

Paleontologists must meticulously document findings and interpret incomplete data. Cognitive styles favoring analytical reasoning, pattern recognition, and systematic problem-solving are common. If you’re constantly noticing connections that others miss, or if you can predict outcomes based on subtle cues, you’re exercising the same mental muscles that paleontologists use daily.

This pattern recognition extends to all aspects of life. You might be the person who figures out office politics before anyone else, or who can tell when a friend is upset even when they insist everything’s fine. Your brain naturally organizes information into meaningful structures, searching for the rules that govern seemingly chaotic systems. It’s the same skill that allows paleontologists to reconstruct ancient ecosystems from scattered fossil evidence.

You Spend More Time Thinking Than Doing

Many paleontologists spend more time on the computer than in the field. This might surprise people who imagine fossil hunting as nonstop adventure. The reality is that deep thinking and analysis dominate the profession. If you’re someone who needs extended periods of mental processing time, who thinks through problems thoroughly before acting, you’re operating in paleontologist mode.

You probably don’t rush to conclusions. Instead, you prefer to sit with information, turning it over in your mind, considering multiple angles before committing to an interpretation. Friends might occasionally find this frustrating when you take forever to pick a restaurant, yet this thoughtful approach serves you well in complex situations where snap judgments lead to mistakes. The contemplative life isn’t for everyone, though for you it feels natural and necessary.

You’re Drawn to Questions Nobody Can Fully Answer

Many paleontologists find that it’s more the unanswered questions that interest them rather than the subject matter itself. Do you find yourself fascinated by mysteries that may never have complete solutions? Maybe you’re intrigued by philosophical questions about consciousness, or you love reading about unsolved historical enigmas. The unknowable doesn’t frustrate you; it energizes you.

This attraction to ambiguity sets you apart. While some people prefer clear answers and established facts, you thrive in spaces where knowledge has edges and boundaries aren’t yet defined. You’re comfortable with the idea that some questions might not have answers in your lifetime, yet that doesn’t diminish your interest in exploring them. It’s the pursuit itself that holds meaning, the intellectual journey through uncertain terrain.

You Have a Weirdly Systematic Approach to Everything

Paleontologists spend a lot of time classifying specimens, looking at their characteristics and how they are related to each other. If you’re the type who creates elaborate systems for organizing everything from your closet to your thoughts, congratulations. You’re basically doing what paleontologists do when they categorize ancient life forms.

This systematic thinking shows up in unexpected places. Maybe you have a specific order for your morning routine that you can’t deviate from, or perhaps you’ve developed your own classification system for music or movies that makes perfect sense to you. Paleontologists are curious, methodical, rational, analytical, and logical. Some of them are also enterprising, meaning they’re adventurous, ambitious, assertive, extroverted, energetic, enthusiastic, confident, and optimistic. Your mind craves structure and organization, finding satisfaction in creating order from chaos.

You Can Hold Multiple Conflicting Theories Simultaneously

Inferring the behavior and function of ancient organisms is hard. Some paleontologists would say that it cannot be done because such hypotheses can never be testable, whereas others would say that this is surely a prime task for paleontology. If you’re comfortable entertaining several contradictory explanations for the same phenomenon without needing to immediately pick one, you’re thinking like a scientist working at the edges of knowledge.

This mental flexibility is surprisingly uncommon. Most people feel compelled to choose a side, to commit to one explanation and defend it. You, however, can keep multiple possibilities alive in your mind, weighing evidence without prematurely collapsing into certainty. It’s not indecisiveness; it’s intellectual humility, recognizing that reality is often more complex than any single explanation can capture. This ability to tolerate ambiguity makes you remarkably adaptable when new information challenges existing beliefs.

You Find Deep Meaning in Objects Others Overlook

Individual fossils may contain information about an organism’s life and environment. Paleontologists see entire worlds in fragments of bone or ancient pollen. Similarly, you might be the person who treasures seemingly mundane objects because of the stories they contain. That old letter, that worn coin, that faded photograph. They’re not just things to you; they’re portals to understanding something larger.

This habit reflects a particular kind of imagination. Reconstructing ancient life forms and ecosystems requires creative thinking. The ability to think abstractly and hypothesize beyond available evidence is vital, aligning with theories of divergent thinking in scientific innovation. You can look at ordinary objects and extrapolate entire narratives from minimal clues, seeing significance where others see clutter. This gift for finding meaning in the overlooked makes you an excellent listener and observer, someone who notices the details that reveal deeper truths about people and situations.

Conclusion

These subtle habits aren’t just random personality quirks. They’re the same cognitive patterns and behavioral tendencies that define how paleontologists approach their work. Whether you’re organizing your garage with methodical precision or pondering questions that have no clear answers, you’re engaging with the world through a lens that values patience, pattern recognition, and the pursuit of understanding.

The fascinating thing is that you don’t need to study fossils professionally to benefit from these traits. They serve you well in countless situations, from solving problems at work to navigating complex relationships. Recognizing these patterns in yourself might help you understand why certain tasks feel natural while others feel like swimming upstream. You’re wired to dig deep, think systematically, and find meaning in fragments of information.

So what do you think? Do these habits sound familiar, or did something here surprise you? Tell us in the comments.