The concept of dinosaur domestication presents a fascinating alternative prehistory that merges paleontology with speculative evolution. For over 160 million years, dinosaurs dominated Earth’s ecosystems, evolving into countless species with diverse biological adaptations and ecological niches. While we know humans have domesticated numerous animals throughout our comparatively brief existence, the question of whether intelligent dinosaurs might have done the same remains a thought-provoking exercise in scientific imagination. This article explores this theoretical scenario by examining the biological, ecological, and cognitive factors that would influence dinosaur domestication, drawing parallels with human domestication practices while acknowledging the significant differences between dinosaur biology and mammalian biology.

The Prerequisites for Domestication

Before considering whether dinosaurs could have domesticated other species, we must understand what domestication requires. Domestication is not merely taming individual animals but selectively breeding populations over generations to enhance desirable traits. This process typically requires the domesticator to possess advanced cognitive abilities, including foresight, planning, and an understanding of heredity. Additionally, the species being domesticated must possess certain biological and behavioral characteristics that make them amenable to human control, such as hierarchical social structures, precocial young, and manageable defensive reactions. The domestication process also requires substantial resource investment and infrastructure development, suggesting that any dinosaur species capable of domestication would need to have reached a certain level of societal organization and technological capability.

Cognitive Capabilities of Advanced Theropods

Among dinosaurs, certain theropods like Troodontids and Dromaeosaurids (including Velociraptor) demonstrated the highest encephalization quotients, suggesting relatively advanced cognitive abilities. Troodon, for example, had one of the highest brain-to-body mass ratios of any dinosaur, comparable to some modern birds. Studies of dinosaur neuroanatomy reveal enlarged cerebral hemispheres and visual processing centers in these species, potentially enabling complex problem-solving and social behaviors. While their intelligence likely didn’t match modern corvids or primates, these dinosaurs may have possessed sufficient cognitive sophistication to conceive of controlling other species. However, even with advanced cognition, the conceptual leap to deliberate selective breeding would require additional cognitive adaptations that may not have evolved in the dinosaur lineage.

Social Structures and Communication

Successful domestication would require sophisticated communication systems among the domesticating species. Evidence suggests some dinosaurs, particularly social theropods and certain hadrosaurs, maintained complex social structures with potential for advanced communication. Hadrosaurs’ elaborate head crests likely served as resonating chambers for communication, while pack-hunting behaviors in dromaeosaurids indicate coordinated social activities. These social dinosaurs would have needed methods to communicate intentions, coordinate activities, and maintain hierarchical structures within their species before attempting to control others. The fossil record provides tantalizing hints of such capabilities, including evidence of pack hunting in Deinonychus and potential parental care in numerous species, but determining whether these social structures could support domestication activities remains speculative.

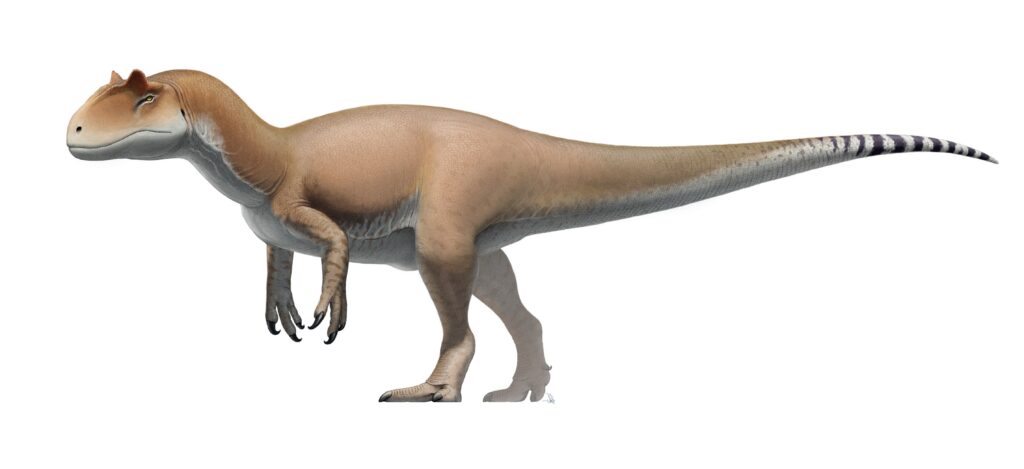

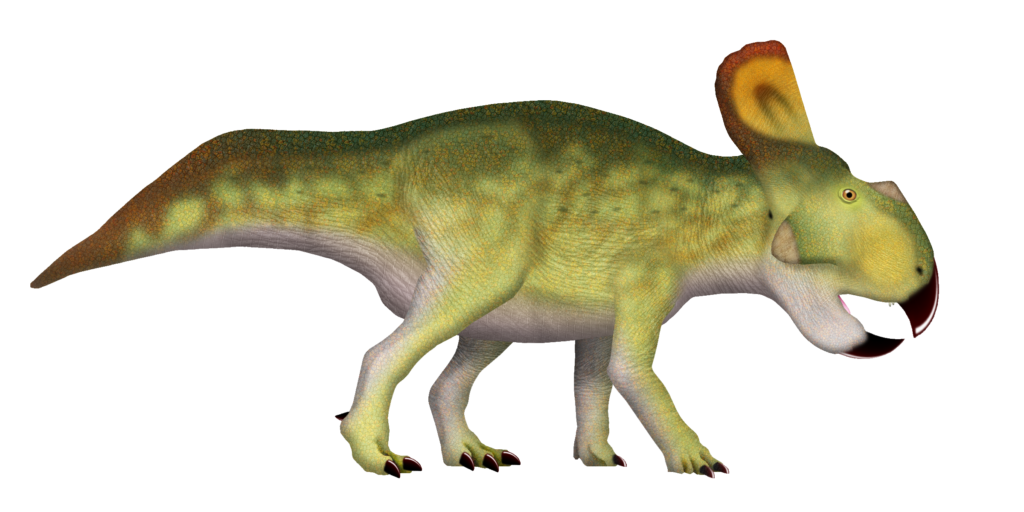

Candidate Species for Domestication

Not all dinosaur species would make suitable candidates for domestication. The ideal candidates would share characteristics with successfully domesticated modern animals, including moderate size, manageable temperament, and rapid reproductive cycles. Small ceratopsians like Protoceratops, which grew to sheep-size and likely lived in herds, might have made suitable livestock analogues. Pachycephalosaurs, with their herbivorous diets and potential herd behavior, could have served as manageable food sources. For labor or transportation, smaller sauropods or sturdy ornithopods might have proven useful if their growth rates could be managed through selective breeding. The key factor would be finding species that reached sexual maturity relatively quickly while exhibiting behavioral traits amenable to control, such as clear dominance hierarchies that could be exploited by dinosaurian handlers.

Dinosaurs as Working Animals

Much like humans domesticated horses, oxen, and elephants for labor, an intelligent dinosaur species might have utilized other dinosaurs for work purposes. Medium-sized sauropods could have served as living cranes or transportation platforms, leveraging their extraordinary strength and endurance. Certain ornithopods with powerful legs might have been selected for speed and endurance as messenger animals or for rapid transportation. Ankylosaurs, with their tank-like bodies, could potentially have been developed into living battering rams or defensive perimeter guards. The practicality of such arrangements would depend heavily on the technological level achieved by the domesticating species, as controlling multi-ton animals would require sophisticated harnesses, enclosures, and training techniques that would need to evolve alongside domestication practices.

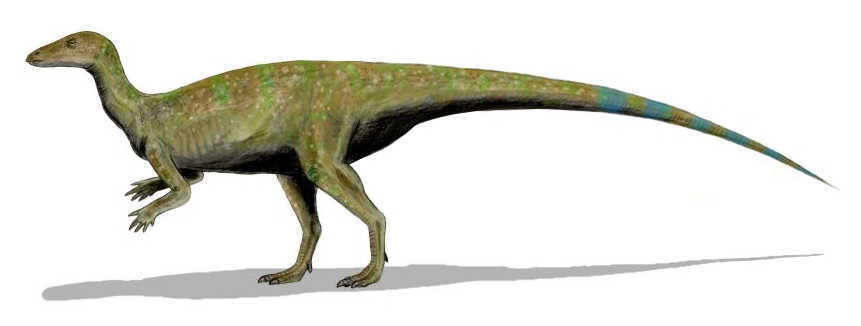

Dinosaurs as Food Sources

Domestication for food production represents perhaps the most practical application for a hypothetical dinosaur civilization. Small to medium-sized herbivores, particularly fast-growing ornithischians, would make ideal candidates for meat and egg production. Hypsilophodontids, with their modest size and presumably rapid growth rates, might have been the prehistoric equivalent of chickens or rabbits. Larger species like hadrosaurs could have served as high-volume meat producers, similar to modern cattle. The complex digestive systems of herbivorous dinosaurs might also have been exploited for secondary products like specialized digestive enzymes or fermented plant materials. However, the energy economics of raising large dinosaurs might have presented significant challenges, potentially favoring smaller species with more efficient conversion rates of plant matter to body mass.

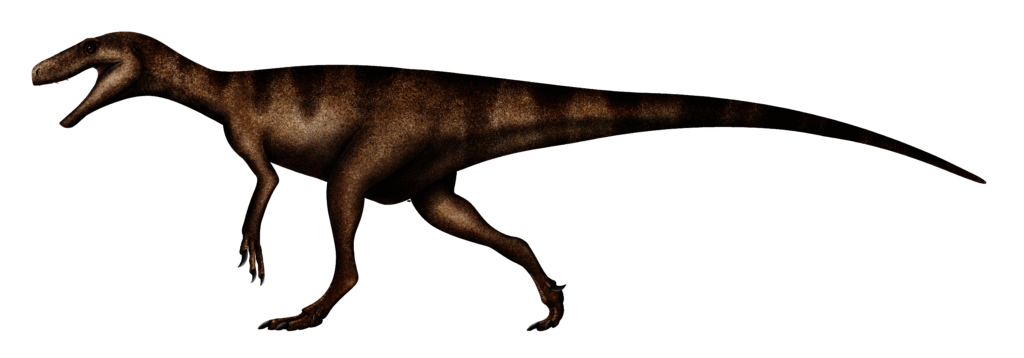

Dinosaurs as Companions and Defenders

The human-dog relationship demonstrates how domestication can create loyal companions and defenders. Similarly, intelligent dinosaurs might have domesticated smaller theropods or dromaeosaurids for protection, hunting assistance, or companionship. Small coelurosaurs with their agility and potentially trainable intelligence could have served as the prehistoric equivalent of hunting dogs. Microraptor-like gliding dinosaurs might have been developed into message carriers or scouts. The pack-hunting instincts observed in fossils of certain dromaeosaurids suggest these animals already possessed social structures that could be redirected toward cooperation with another species. The key would be selecting species small enough to be safely controlled while retaining useful hunting or defensive capabilities that complement the domesticating species’ needs.

Biological Challenges to Dinosaur Domestication

Significant biological hurdles would have complicated dinosaur domestication efforts. Many larger dinosaur species likely had extended growth periods and reached sexual maturity over many years, making selective breeding a multi-generational enterprise even for the domesticators. Dinosaur reproduction through egg-laying presents both advantages (potential for artificial incubation) and challenges (vulnerability of eggs to predation or environmental factors). Additionally, the metabolic needs of dinosaurs might have required specialized feeding regimes difficult to maintain in captive settings. The massive size difference between many dinosaur species would create practical containment issues, potentially requiring substantial infrastructure development before domestication could succeed. These biological realities would have shaped which species could realistically be domesticated and for what purposes.

Evolutionary Timeframes for Domestication

Human domestication of animals unfolded over thousands of years, a blink in evolutionary time. Dinosaurs existed for over 160 million years, theoretically providing ample time for both the evolution of intelligence and subsequent domestication practices to develop. If an intelligent dinosaur lineage emerged in the late Cretaceous, for instance, it might have had millions of years to develop domestication techniques before the extinction event. Alternatively, had the extinction event not occurred, continued cognitive evolution in certain theropod lineages might eventually have produced species capable of domestication behaviors. The fossil record suggests cognitive capabilities in dinosaurs were on an upward trajectory, with brain-to-body ratios increasing in certain lineages over time. This pattern mirrors what we observe in mammalian evolution and suggests that the basic preconditions for domestication could eventually have emerged.

Ecological Impact of Dinosaur Domestication

The ecological consequences of dinosaur domestication would have been profound. Just as human agriculture has transformed landscapes, dinosaur “agriculture” would have required clearing land, redirecting water resources, and potentially causing habitat fragmentation. Large herbivorous dinosaurs under domestication would require vast feeding grounds, potentially leading to specialized plant cultivation. Waste management would present significant challenges, though this might have been turned to advantage through the fertilization of crops. The concentration of certain species in domestic settings might have created disease reservoirs and transmission opportunities, potentially driving the evolution of zoonotic pathogens. Escaped domestic dinosaurs could become invasive species in new habitats, disrupting established ecological relationships. These environmental modifications would have triggered cascading effects throughout Mesozoic ecosystems, potentially accelerating evolutionary adaptations in both domesticated and wild species.

Cultural Implications of Dinosaur Domestication

Domestication would likely have profound effects on the culture and social organization of an intelligent dinosaur species. The development of animal husbandry typically coincides with transitions from nomadic to settled lifestyles, as seen in human history. Dinosaur settlements would likely emerge around productive domestication centers, leading to increasingly complex social hierarchies and specialized roles. Trade networks might develop to exchange particularly successful domestic dinosaur lineages between different regions. Religious or spiritual practices might incorporate domesticated species as sacred animals or sacrificial offerings. The relationship between dinosaur keepers and their charges might even have influenced the development of dinosaurian art, music, or other cultural expressions. Ultimately, domestication could have catalyzed civilization development, much as it did for humans.

Alternative Pathways to Dinosaur-Dinosaur Relationships

True domestication represents just one potential relationship between intelligent dinosaurs and other species. Commensalism or mutualism might have provided alternative evolutionary pathways to interspecific cooperation. Small dinosaurs might have evolved to live alongside larger, intelligent species, providing pest control or scavenging services in exchange for protection and food scraps. This arrangement would mirror the proposed early stages of wolf-human relationships before formal domestication. Alternatively, intelligent dinosaurs might have developed sustainable harvesting practices of wild populations rather than true domestication, similar to some indigenous human approaches to resource management. Captive breeding programs for particularly useful species might have emerged as an intermediate step between hunting and full domestication. These alternative arrangements might have proven more practical given the biological constraints of dinosaur species.

Scientific Speculation vs. Fantasy

When exploring hypothetical dinosaur domestication, distinguishing between scientific speculation and pure fantasy is crucial. While this thought experiment is inherently speculative, it can be grounded in paleontological evidence, comparative biology, and evolutionary principles. The fossil record provides concrete evidence about dinosaur biology, behavior, and cognitive capabilities that constrain our speculation. Similarly, studying the patterns of domestication across human history and the biological prerequisites for successful domestication provides a framework for assessing which dinosaur species might have been domesticable. By applying these scientific principles, we can engage in informed speculation that, while impossible to prove definitively, remains consistent with our understanding of evolution and animal behavior. This approach transforms what might otherwise be mere fantasy into a valuable exercise in evolutionary thinking and comparative biology.

Conclusion: The Unrealized Potential

The question of dinosaur domestication ultimately remains a fascinating thought experiment rather than a historical possibility. While certain dinosaur lineages showed promising cognitive development and social structures that might eventually have led to domestication capabilities, the K-Pg extinction event cut short this evolutionary trajectory. Instead, it was the descendants of small, surviving theropod dinosaurs—birds—and mammals that would go on to develop the intelligence necessary for domestication practices. Today, in a remarkable evolutionary twist, humans have domesticated modern dinosaurs in the form of chickens, ducks, and other poultry, making them among our most numerous domestic animals. This reality underscores the profound interconnectedness of evolutionary pathways and reminds us that while dinosaur-dinosaur domestication never occurred, the potential for such relationships existed within the dinosaurian genome, ultimately expressed millions of years later through entirely different evolutionary pathways.