Dinosaurs dominated Earth for over 165 million years, yet their technological achievements remained at zero. Meanwhile, mammals—particularly humans—evolved from small, primitive creatures to become Earth’s dominant technological species in just a few million years. This striking contrast raises a fascinating question: had the asteroid impact not occurred 66 million years ago, would dinosaurs eventually have developed tool use and perhaps even advanced technology? This thought experiment sits at the intersection of paleontology, evolutionary biology, and cognitive science, challenging us to reconsider our assumptions about intelligence, evolution, and the uniqueness of human technological development.

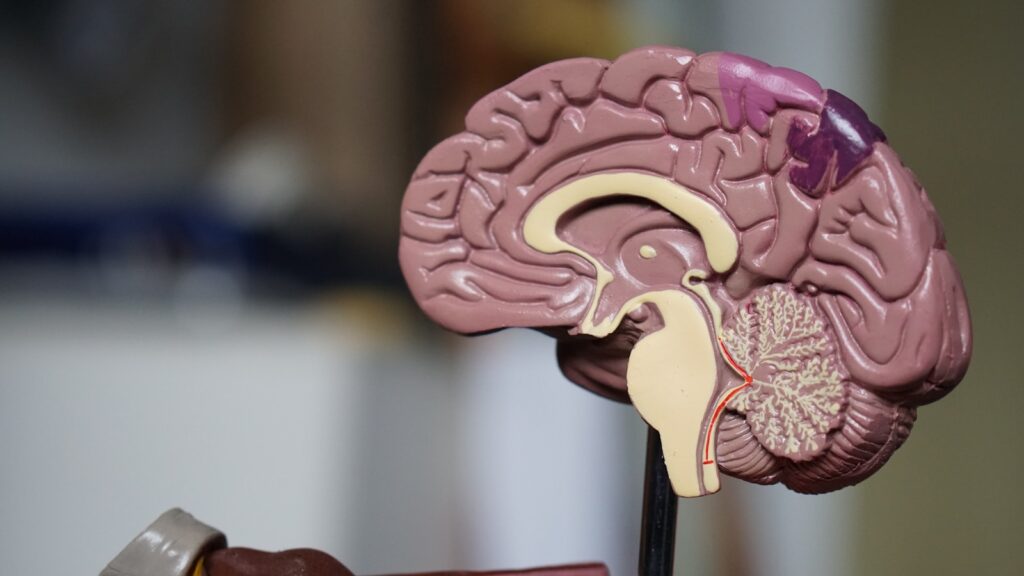

The Cognitive Prerequisites for Tool Use

Before considering whether dinosaurs could have invented tools, we must understand what cognitive abilities enable tool use in the first place. Advanced tool creation requires several mental capacities: problem-solving skills, creativity, memory, and often social learning. These capabilities are linked to brain structure, particularly the cerebral cortex in mammals. Even the most basic intentional tool use demands a level of cognitive complexity that allows an animal to understand cause and effect relationships and manipulate objects with specific outcomes in mind. Today’s tool-using animals—including crows, chimpanzees, and octopuses—demonstrate these abilities through their behaviors, suggesting that tool use emerges when certain cognitive thresholds are crossed, regardless of an animal’s evolutionary lineage.

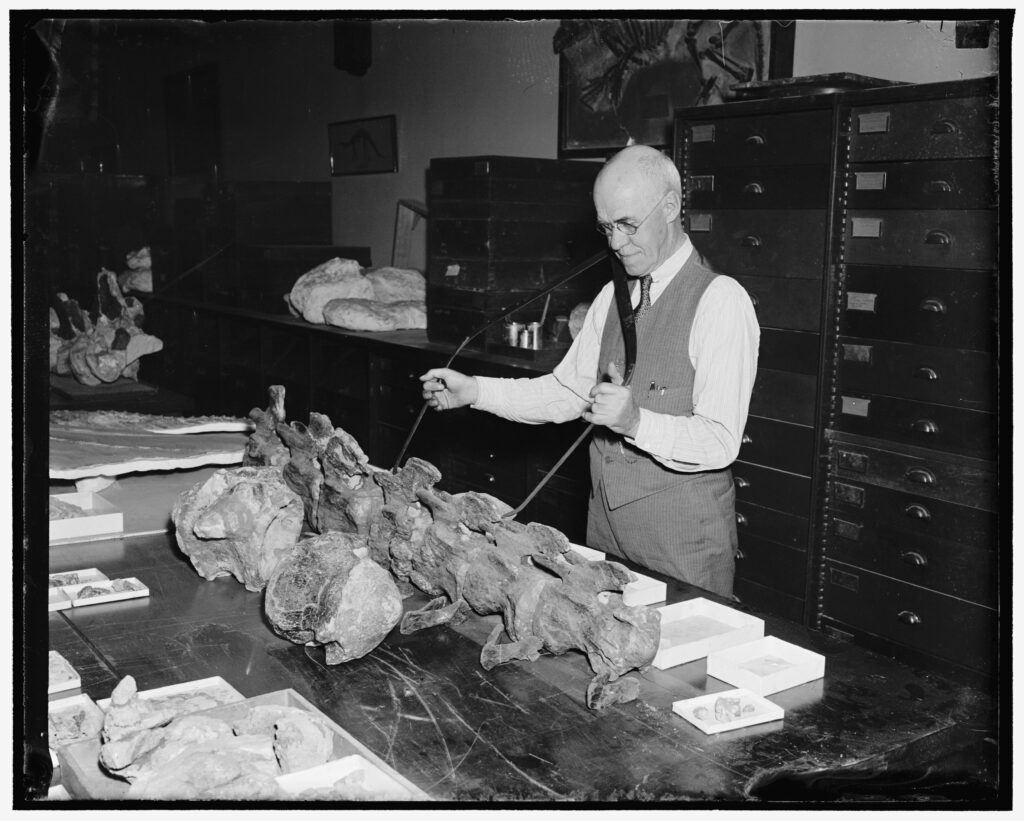

What We Know About Dinosaur Brains

Paleontologists have made significant progress in understanding dinosaur neuroanatomy through endocasts—models of the brain cavity that provide insights into brain size and structure. The encephalization quotient (EQ), which measures brain size relative to body size, varies considerably among dinosaur species. Some theropods, particularly dromeosaurs and troodontids, possessed relatively larger brains for their body size compared to other dinosaurs. Troodontids, for instance, had EQs approaching those of modern birds, suggesting potentially higher cognitive abilities. However, brain structure matters as much as size, and dinosaur brains generally lacked the neocortex that enables complex cognition in mammals. Instead, they possessed enlarged structures analogous to the avian pallium, which supports different but potentially sophisticated forms of intelligence in modern birds.

Tool Use in Modern Birds: The Dinosaur Connection

Birds, as the only surviving dinosaur lineage, provide our best window into potential dinosaur cognitive capabilities. Several bird species demonstrate remarkable tool use: New Caledonian crows craft specialized tools from materials, Egyptian vultures break ostrich eggs with stones, and finches use cactus spines to extract insects. These behaviors reveal sophisticated problem-solving abilities despite birds having fundamentally different brain structures than mammals. The presence of these capabilities in modern birds suggests that the neurological foundations for tool use existed within the dinosaur lineage. This strengthens the possibility that, given enough time and appropriate evolutionary pressures, non-avian dinosaurs might have developed similar cognitive traits, especially considering the close relationship between birds and certain theropod dinosaurs like Deinonychus and Velociraptor.

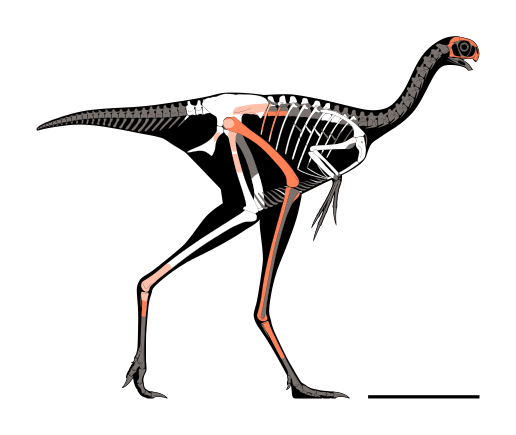

The Anatomy Question: Physical Constraints on Tool Use

Cognitive ability alone doesn’t guarantee tool development—physical anatomy plays a crucial role as well. Most non-avian dinosaurs lacked specialized manipulative appendages comparable to human hands. Tyrannosaurids had reduced forelimbs with just two functional digits, while many herbivorous dinosaurs possessed limbs adapted primarily for locomotion or defense. However, certain theropods, particularly maniraptoran dinosaurs like Deinonychus, possessed relatively dexterous forelimbs with three-fingered hands capable of grasping. These anatomical features, combined with evidence of precise motor control, suggest that some dinosaur lineages possessed the physical capabilities necessary for basic tool manipulation. The diversity of dinosaur body plans also means that different groups would have faced different constraints and opportunities regarding potential tool use.

Evolutionary Pressure: The Necessity Question

Tool use typically evolves as a solution to specific environmental challenges, emerging when the benefits outweigh the cognitive and physiological costs of developing such abilities. For dinosaurs, the evolutionary pressures would have differed significantly from those faced by primates. Large-bodied dinosaurs enjoyed advantages in predator-prey relationships that may have reduced selection pressure for tool development. Their specialized feeding adaptations, like the beaks of ceratopsians or the massive jaws of tyrannosaurs, already solved many food acquisition problems without requiring tools. However, smaller dinosaur species might have benefited from tool use to access otherwise unavailable food sources or to compete more effectively. Changing environmental conditions in a post-Cretaceous world might have created new selection pressures favoring cognitive adaptations, potentially including tool use in certain lineages.

The Intelligence Trajectory: Were Dinosaurs Getting Smarter?

Examining the fossil record reveals intriguing trends in dinosaur brain evolution over their 165-million-year reign. Later theropods, particularly those closest to the bird lineage, show evidence of increased relative brain size compared to earlier species. The most intelligent dinosaur groups—troodontids and other paravians—appeared relatively late in dinosaur evolutionary history, suggesting a potential upward trajectory in cognitive capabilities. Some paleontologists argue that certain dinosaur lineages were undergoing a “cognitive radiation” similar to what occurred in mammals after the extinction event. If this trajectory had continued uninterrupted, it’s conceivable that some dinosaur groups might have eventually developed the neural architecture necessary for more complex problem-solving, potentially including rudimentary tool use. This pattern suggests dinosaur intelligence was not static but followed evolutionary pathways that might have led to more sophisticated cognition.

The Social Factor: Cooperation and Cultural Transmission

Complex tool use in humans and other species often depends on social learning and cultural transmission of knowledge. Evidence suggests many dinosaur species were social animals, with some forming complex herds or packs. Trackway fossils show coordinated group movements, while nesting sites indicate communal breeding behaviors in certain species. These social structures could have provided a foundation for information sharing and observational learning. Particularly promising candidates for social intelligence include dromaeosaurs like Velociraptor, which show adaptations suggesting pack hunting behaviors. The evolution of complex sociality might have created conditions favorable for the emergence of culturally transmitted behaviors, including potential tool use. Social living also tends to select for enhanced communication and theory of mind—cognitive abilities that support technological development.

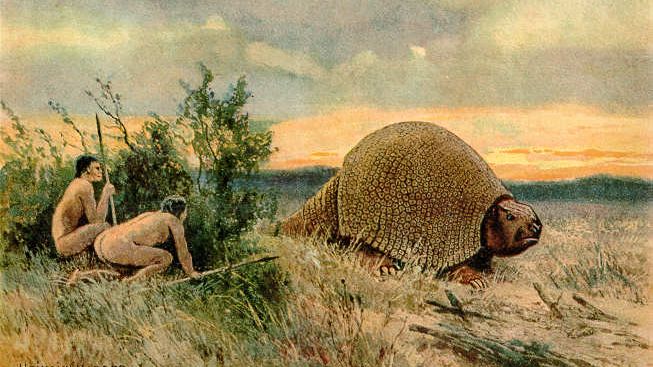

Alternative Paths to Technology: Non-Primate Models

Our understanding of technological evolution needn’t be limited to the primate model that led to human tool use. Throughout the animal kingdom, diverse species have developed unique solutions to environmental challenges. Octopuses demonstrate remarkable problem-solving despite having a nervous system radically different from vertebrates. Beavers create complex environmental modifications without primate-like hands. Even insects like leaf-cutter ants practice a form of agriculture. These examples suggest multiple evolutionary pathways to complex adaptive behaviors that could be considered technological. Dinosaurs might have developed entirely different approaches to environmental manipulation based on their unique anatomical and neurological characteristics. Their potential technological trajectory would likely have differed dramatically from the primate path, perhaps emphasizing beak-based manipulation in certain lineages or cooperative environmental modification in others.

The Time Factor: Evolutionary Timescales and Innovation

Evolutionary innovation operates on vast timescales, with significant changes often requiring millions of years. Dinosaurs already had 165 million years of evolutionary history when the asteroid struck—nearly three times the amount of time since the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs. Yet in the mere 66 million years since the K-Pg extinction, mammals evolved from small, generalized forms to produce technological humans. This disparity raises questions about evolutionary rates and constraints. Some scientists suggest that dinosaur evolution had reached an adaptive plateau, while others argue that their diversity indicates continued evolutionary potential. The relatively rapid brain evolution in certain dinosaur lineages suggests their cognitive development was still actively progressing. Given another 65 million years—the time it took mammals to produce humans—it’s conceivable that some dinosaur lineages might have achieved significant cognitive and technological advances, though the specific form these might have taken remains necessarily speculative.

Specific Candidates: Which Dinosaurs Had the Most Potential?

Not all dinosaur lineages showed equal potential for developing advanced cognitive abilities. Based on current evidence, several groups stand out as particularly promising candidates. Troodontids, with their relatively large brains, binocular vision, and dexterous forelimbs, possessed a combination of features conducive to tool use. These small, likely nocturnal dinosaurs might have faced selection pressures favoring enhanced problem-solving abilities. Certain dromaeosaurs like Deinonychus and Velociraptor combined manual dexterity with evidence of social behavior, creating conditions that could have supported cultural transmission of tool use if it emerged. Ornithomimosaurs, with their ostrich-like build and three-fingered hands, represent another group with physical capabilities potentially compatible with tool manipulation. The most likely scenario would have involved multiple lineages developing different forms of environmental manipulation tailored to their ecological niches, rather than a single group following a human-like trajectory.

Beyond Basic Tools: The Technological Threshold

The leap from simple tool use to complex technology represents a significant cognitive threshold. This transition requires not just using found objects, but deliberately modifying materials to create new tools and eventually using tools to make other tools. In humans, this development was accompanied by language, abstract thinking, and material culture—all supported by our particular neurological adaptations. Whether dinosaurs could have crossed this threshold depends on their capacity for cumulative culture and abstract reasoning. The neurological structures supporting these abilities in mammals differ from those in birds, suggesting dinosaurs might have developed alternative cognitive pathways to technological thinking. Some researchers speculate that continued evolution of the avian-style pallium in dinosaur brains might have eventually supported complex innovation through different neural mechanisms than those used by primates. Without the asteroid impact, dinosaurs would have had millions more years for such alternative cognitive architectures to evolve and potentially reach technological thresholds.

Alternate Histories: Dinosaur Civilizations?

Speculative fiction often portrays intelligent dinosaurs developing civilizations similar to human societies, complete with buildings, writing, and advanced technology. While entertaining, such scenarios require substantial evolutionary changes beyond mere tool use. True technological civilization requires not just intelligence but specific adaptations supporting abstract reasoning, communication systems, and manipulative abilities. The developmental pathway to dinosaur technology would likely have produced radically different outcomes than human civilization due to their different physiological starting points. Rather than humanoid dinosaurs building recognizable cities, a more plausible scenario might involve certain small theropods developing limited material cultures, perhaps using found objects and minimally modified tools for specific purposes. Any dinosaur “technology” would have been shaped by their particular anatomical constraints and ecological needs, potentially producing innovations without parallel in human history.

What Evolution Teaches Us About Technological Inevitability

The evolution of human-level technology was not preordained but resulted from a specific confluence of factors including our particular neural architecture, manual dexterity, ecological pressures, and social structures. The relatively recent emergence of human technology, after billions of years of Earth’s evolutionary history, suggests technological intelligence is not an inevitable outcome of evolution. Instead, it represents just one of countless possible adaptive strategies. Multiple animal lineages have achieved remarkable success without developing technology, suggesting alternative evolutionary pathways to fitness. Dinosaurs thrived for 165 million years through adaptations like gigantism, specialized feeding structures, and elaborate defensive features—strategies quite different from technology development. This evolutionary perspective cautions against assuming that technology represents a universal pinnacle of evolution that all successful lineages would eventually achieve, while still acknowledging that given sufficient time, alternative forms of environmental manipulation might emerge in diverse lineages under the right conditions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while dinosaurs never developed tools during their long reign, the question of whether they could have eventually done so had they survived remains tantalizingly open. The cognitive capabilities demonstrated by their avian descendants, combined with evidence of increasing brain size in certain theropod lineages, suggests the basic neurological foundation for tool use existed within the dinosaur family tree. Physical constraints would have shaped any potential dinosaur technology differently from human tools, likely favoring different forms of environmental manipulation suited to their unique anatomy. Given millions more years of evolution, it seems plausible that at least some dinosaur lineages might have developed simple tools and perhaps even more complex technologies, though these would have followed evolutionary pathways distinct from the primate model. This thought experiment reminds us that intelligence and technology are not singular, inevitable outcomes of evolution, but rather specific adaptations among many possible evolutionary trajectories.